August 6, 1939: Late home runs lift West to win in Negro League all-star game

As the Cheers resident know-it-all Cliff Clavin might have said, “It’s a little-known fact …” that the first major-league All-Star Game held at Comiskey Park in 1933 was not the only inaugural All-Star competition held that year at the ballyard that Charles built.

As the Cheers resident know-it-all Cliff Clavin might have said, “It’s a little-known fact …” that the first major-league All-Star Game held at Comiskey Park in 1933 was not the only inaugural All-Star competition held that year at the ballyard that Charles built.

Following on the heels of the Comiskey classic, Pittsburgh Crawfords Secretary Roy Sparrow and Pittsburgh Courier editor Bill Nun discussed the idea of having a similar game pitting the best players from the newly constituted Negro National League against each other.1 Their initial idea was to hold the game at Yankee Stadium, but after receiving a tepid response to that suggestion, Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee recommended that the game be held at Comiskey because it would appeal to the Windy City’s large black population. The West won the first game, 11-7, on September 10, 1933, in front of approximately 20,000 rain-soaked fans. The game was a success and a new tradition was born.

With the organization of the Negro American League in 1937, the game pitted the best players from the two circuits against each other. Because Negro National League teams were based in the East, and Negro American League teams played in the Midwest, it was easy to continue calling the event the East-West All-Star game.

The game grew in popularity as the pressures of the Depression eased. It helped that neither league dominated, as the two sides split the first games evenly, with three wins apiece. The first six games set the stage for one of the classic matchups in the event’s history. On August 6, 1939, the West used home-run power in the seventh and eighth innings to overcome a 2-0 East lead in front of 40,000 fans, a record attendance for the classic up to that time.

Fans voted for the players on each side from ballots available through America’s three leading black community newspapers, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Kansas City Call, and the Chicago Defender. Even though they were only voting for baseball All-Stars, the right to do so was important to many African-Americans because many were denied the right to exercise their franchise under existing Jim Crow laws.

“(D)uring the 1930s, voting was so difficult for blacks that many did not bother,” wrote Bo Smolka in his history of the Negro Leagues. “So the chance to vote for the East-West All-Star Game players was a big deal. More than 17 million ballets were submitted for the 1939 East-West Game.”2

“That was a pretty important thing for black people to do in those days, even if it was just for ballplayers,” said Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil.3

Those votes resulted in a lot of talented players participating in the game, including future Hall of Famers Willie Wells, Josh Gibson, Mule Suttles, Leon Day, and Buck Leonard for the East squad, and Hilton Smith for the West.

The weather was perfect as heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis arrived wearing a snazzy gabardine suit to throw out the first pitch to Greenlee. Once the game started, the favored Easterners scored two runs in the second inning off starter Theolic Smith of the Memphis Red Sox. The rally started when Leonard was safe on an error by shortstop Ted Strong. Leonard advanced to third on Pat Patterson’s single, and after Patterson stole second, both runners scored on a single by Sammy Hughes.

Both sides pitched well over the next several innings as the score remained 2-0. In fact, keeping East sluggers Gibson, Suttles, and Leonard hitless (the three went 0-for-10) allowed the West to mount their comeback.

“At this point (the second inning) the hopes of the thousands of Western rooters hit a new ‘low,’ but still the West’s pitching continued on a high plane,” wrote Chester L. Washington Jr. “Eastern base hits were as scarce as hen’s teeth and soon the hopes of the West started to soar again.”4

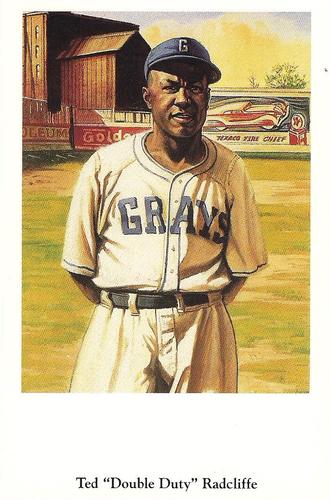

That soaring began in the seventh inning when Neil Robinson broke the East’s shutout bid, blasting Roy Partlow’s first offering 380 feet into the second tier of the left-field stands. The West completed their comeback in the eighth. Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe singled to center, and was sacrificed to second by Parnell Woods. Dan Wilson followed that with a two-run homer that put the West in the lead to stay. After Bill Holland replaced Partlow, Double Duty’s brother Alec greeted him with a base hit. Robinson then hit a fly ball that Suttles lost in the sun. Radcliffe reached third on the play while Robinson landed on second with a double. The West showed what small ball is about when Billy Horne hit a sacrifice that brought Double Duty home with an insurance run. Double Duty Radcliffe pitched a 1-2-3 ninth and earned the victory for the West while Partlow was tagged with the loss.5

“With one bold stroke of his bat, this artist of the diamond painted a picture before the astonished eyes of some 40,000 fans … a painting as dramatic in its highlights and shadows as Rembrandt’s [sic] ‘Blue Boy,’” wrote Bill Nun about Wilson’s homer.6 “Dan Wilson today stole the thunder of the vaunted power-hitters of the East.”7

The West’s victory gave them a 4-3 lead in the series, and helped them maintain a dominance they held for the duration of the series’ existence. The East-West All-Star Game was held annually at Comiskey Park until 1960, with the West winning 16 of the 28 matchups. The last two Classics were held at Yankee Stadium in 1961 and at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium in 1962, with the West winning both contests, 7-1 in 1961 and 5-2 in 1962.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author also used:

Negro League Baseball E-museum.

Thenationalpastimemuseum.com.

Finder, Chuck. “Negro Leagues Converged in an East Meets West Powerball Summit,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 9, 2006.

Kleinknecht, Merl F. “East Meets West in Negro All-Star Game,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1972.

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Newman, Roberta. Shadow Culture, Shadow Game: The Negro Leagues.

Sullivan, Floyd, editor. Old Comiskey Park: Essays and Memories of the Historic Home of the Chicago White Sox, 1910-1991 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2014).

Notes

1 The first Negro National League, founded in 1920, could not survive the Great Depression and folded in 1931.

2 Bo Smolka, The Story of the Negro Leagues (Minneapolis: ABDO Publishing Company, 2013), 9.

3 Ibid.

4 Chester L. Washington Jr., “Sun Rises in the West,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939: 17.

5 Partlow later played briefly with the Montreal Royals in 1946, the same year Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Organized Baseball.

6 Blue Boy was painted by the Englishman Thomas Gainsborough.

7 William G. Nunn, “Homers by Dan Wilson, Robinson Decide Battle,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939: 17.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.