July 1, 1920: St. Louis Cardinals fall in their first game at Sportsman’s Park

At the end of June 1920 the National League pennant contenders were tightly bunched behind the defending champion Cincinnati Reds. The Brooklyn Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, and St. Louis Cardinals were in a virtual tie for second, three games out. The greatest surprise among these contenders was the Cardinals — the year before, they had finished seventh, 40½ games out.1

At the end of June 1920 the National League pennant contenders were tightly bunched behind the defending champion Cincinnati Reds. The Brooklyn Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, and St. Louis Cardinals were in a virtual tie for second, three games out. The greatest surprise among these contenders was the Cardinals — the year before, they had finished seventh, 40½ games out.1

Thus, as the Cardinals hosted a three-game series against the Pirates beginning July 1, an estimated 20,000 fans came to see their club in action.2 Attendance was no doubt swelled by an annual benefit for the St. Louis Tuberculosis League, which included an assortment of races, field events, and musical entertainment. Local society women walked through the stands selling programs that held the promise of various prizes. An exhibition game involving Army and Navy personnel preceded the Cardinals-Pirates contest at what was described as “the Browns Park,” a descriptive that popular usage would change to “the Cards Park” within a few years.3

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch faithfully covered these events; not until the fourth paragraph of the article did it touch on the day’s most significant development, and then only in passing. The Cardinals were playing their first “Championship contest” (as the Post-Dispatch expressed it), in Sportsman’s Park. It was an occurrence that would have profound implications for the Browns and Cardinals over the ensuing years. This was unrealized in the next day’s coverage of the game. A mundane recounting of the contest carried the day.4

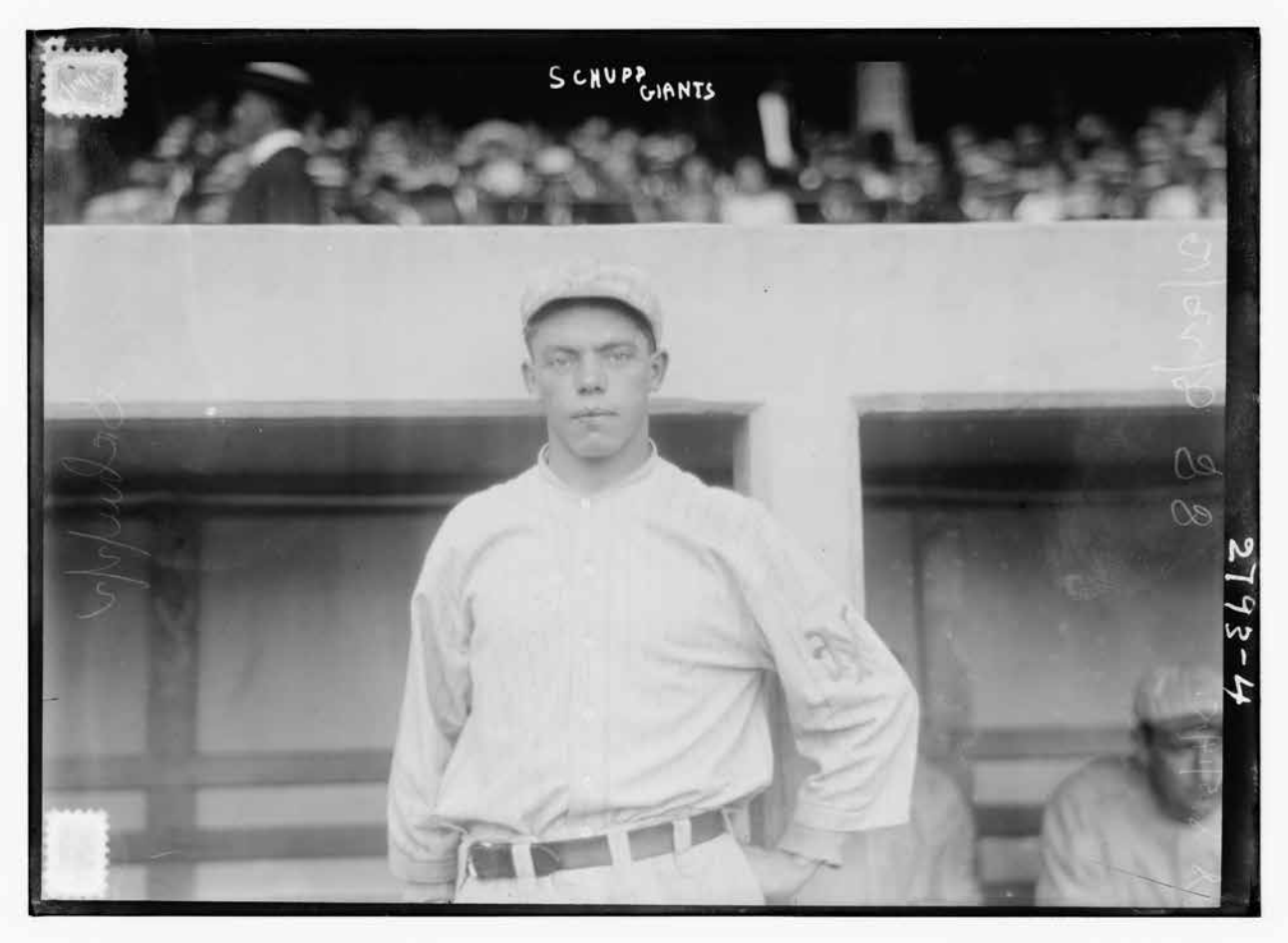

The matchup featured Ferdie Schupp, 8-4 for far, against the Pirates’ Hal Carlson, who began the contest with a 5-6 record. Pittsburgh, in sixth place, just five games behind the Reds (and two behind St. Louis) drew first blood in the third on Carson Bigbee’s triple and Max Carey’s single. Another Pirates tally came the next inning off the bat of Walter Barbare, whose double followed Howdy Caton’s double to make it 2-0.

Carlson held St. Louis scoreless until the bottom of the eighth, when Cliff Heathcote slammed his second home run of the year. St. Louis then tied the game in the bottom of the ninth on Doc Lavan’s double and pinch-hitter Austin McHenry’s one-out single.

Henry had batted for Schupp, whose 10 hits and three walks surrendered remarkably yielded just two runs for Pittsburgh. He was replaced in the 10th by Bill Sherdel, the Cardinals’ main relief pitcher that year. Sherdel had done yeoman work for the club, and would do so for years to come, but this would not be one of his better efforts. He gave up four hits and a walk, aided by first baseman Jack Fournier’s wild throw, as the Pirates scored four times. St. Louis went quietly in the bottom of the inning to give Pittsburgh a 6-2 victory.

The results of the game had no bearing on a pennant race eventually won by Brooklyn. Pittsburgh ended the season in fourth; St. Louis, plagued by ineffective pitching, faded into a tie for fifth, encouraged, however, that at 75-79 they almost reached.500, substantially better than they had done in 1919. Rogers Hornsby, at .370, won the first of six consecutive batting titles, starting a run that included three seasons over .400.

Quite often the importance of a major-league game is measured by the outcome of the contest, often by what might have been accomplished either individually or by either club. In this game Hornsby had two singles in four at-bats. But what he or anyone else accomplished on the field this day was not the significant story. This was the Cardinals’ first home game at Sportsman’s Park, a field they would use for the next 46 years. That the Cardinals could use Sportsman’s Park for their home games would prove of significant importance not only to their franchise but also to their rival St. Louis Browns.

A review of major-league baseball in St. Louis over the years rightfully focuses on the Cardinals. There was a time, however, when the favored team in St. Louis was the American League Browns — not the Cardinals. Until 1926, when the Cardinals won their first pennant and world championship, the Browns regularly outdrew their National League counterparts to the tune of over 50,000 fans per year on average. The Browns were the better team in the early 1920s, and came breathtakingly close to a pennant in 1922, finishing just one game behind the Yankees.

While the Cardinals, in retrospect, might be seen as a greater draw in those years because of Hornsby, the Browns had just as big a pull in first baseman George Sisler. The same year, 1920, that saw Hornsby lead the league with his .370 average, Sisler batted .407 with a then major-league-record 257 hits.

How allegiance gradually shifted from the Browns to the Cardinals was based on several factors. One involved the Cardinals’ promotion of what was called the Knothole Gang, an effort that arranged for free tickets to mostly underprivileged youth. This program gained scores of loyal Cardinals fans for decades. Another development involved Branch Rickey’s move from the Browns to the Cardinals. The Browns’ wealthy, irascible, and unpredictable owner, Phil Ball, did not appreciate Rickey’s talents and Rickey, seeking better opportunities, was lured to the Cardinals. Although he was mediocre as a field manager, his visionary efforts as a general manager in developing an expansive minor-league farm system were peerless. By the time Rickey left the Cardinals in 1942 he had earned the club six pennants and four World Series championships.

Despite these factors, what really cemented the Cardinals’ future in St. Louis — and the Browns’ eventual departure to Baltimore — was how they gained access to Sportsman’s Park, and how it saved the franchise.

By 1920, Robison Field, the Cardinals’ home ballpark for decades, was in a state of serious disrepair. Built in 1893, the wooden structure had outlived its usefulness. Cardinals president Sam Breadon lacked the wherewithal to refurbish it — he estimated it would cost over half a million dollars to do so.5 As the 1920 season approached, the structure had become a firetrap, ready to collapse. Breadon was warned that the ballpark would not pass a fire inspection.6

Desperate, and without the cash to fix the ballpark or build a new one, Breadon approached Ball to see if he could rent Sportsman’s Park for Cardinals home games. Sportsman’s Park had been used by the Browns since 1902 and had received a major overhaul in 1909 with construction of steel and concrete grandstands.

Ball rebuffed Breadon in large part because he was offended at Rickey having left the Browns for the Cardinals years before. “Are you crazy, Sam? I wouldn’t let Branch Rickey put one foot inside my ballpark. Now get out yourself.”7 Facing financial calamity, Breadon was persistent; after several attempts, he finally asked Ball to listen to his plea. Ball relented.

As historian Fred Lieb told it later, Ball told Breadon, “I was a poor boy — a very poor boy — in New York. I came here to St. Louis, nearly starved at first, but eventually made some money in the automobile business. I got into the Cardinals with that fan group — soon got in over my head — and much of my money is in the club. We’re heavily in debt, and our only chance to salvage what we put into it is to sell the Cardinals’ real estate (Robison Field) for $200,000, get out of debt, and move to Sportsman’s Park. You’re a rich man, Mr. Ball; money doesn’t mean anything to you, but I’m about to go broke, and only you can save me.”

Ball respected determination, and behind his blustery façade rested the temperament of a caring man. Breadon’s entreaty hit its mark. “Sam, I didn’t know you were hooked so bad. I admire your frankness, and what’s more I admire a fighter, a man that doesn’t quit easily. Get your lawyer to draw up a contract, insert a rental figure you think is fair and I’ll sign it. Even if it included having that Rickey around the place.”8

With Ball agreeing to take on the Cardinals as tenants, Breadon was able to sell Robison Field for $275,000, clear outstanding debts and provide working capital for the future. One of the main initiatives Breadon and Rickey could now pursue was establishment of the productive minor-league system that would eventually create a competitive team for decades to come.9 This, and a growing allegiance created out of the Knothole Gang, would bury the Browns.

By itself the game of July 1, 1920, between the Cardinals and Pirates was of no great importance in the scheme of things. Where it was played would prove to have a lasting impact on two major-league franchises.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Photo Caption

Ferdie Schupp, who posted a 61-39 record in his 10-year career (1913-1922), was the Cardinals’ starter in their first game in Sportsman’s Park. (Library of Congress)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Cards’ Biggest Local Attendance This Year, Welcomes Team Home,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 1, 1920: 37.

2 “National League,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1920: 6.

3 “Cards Biggest Local Attendance.”

4 Edward P. Balinger, “Sherdel Hammered for Four Hits in Vicious Exhibition,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 2, 1920: 10.

5 Joan M. Thomas, “Robison Field,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/88929e79.

6 Mark Armour, “Sam Breadon,” in The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals, The World Champion Gas House Gang (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2014): 239.

7 Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns, (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000), 267.

8 Frederick G. Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles: The History of a Colorful Team in Baltimore and St. Louis, (Carbondale, Ilinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1955),191-192.

9 Armour. 239

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 6

St. Louis Cardinals 2

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.