July 1, 1934: Dizzy and Ducky lead Cardinals to marathon victory in Cincinnati

It was a “titanic struggle,” declared sportswriter Jack Ryder about the longest, and surely one of the most exciting, games of the 1934 major-league season.1 It featured seven lead changes, clutch hitting, sensational defense, rubber-armed pitching, and some luck.

It was a “titanic struggle,” declared sportswriter Jack Ryder about the longest, and surely one of the most exciting, games of the 1934 major-league season.1 It featured seven lead changes, clutch hitting, sensational defense, rubber-armed pitching, and some luck.

The Cincinnati Reds were having another abysmal season when they engaged the St. Louis Cardinals in a doubleheader on Sunday, July 1, to conclude a four-game series in the Queen City. Player-manager Bob O’Farrell’s squad (21-43) was the NL’s worst team, 19½ games behind the front-running New York Giants and headed to their fourth consecutive last-place finish. The Redbirds were one of the senior circuit’s most successful teams, having captured four pennants in a six-year stretch (1926-1931). After two uncharacteristic second-division finishes, player-manager Frankie Frisch had his club back in the thick of a title hunt, in third place (38-27), three games behind their Gotham City rivals.

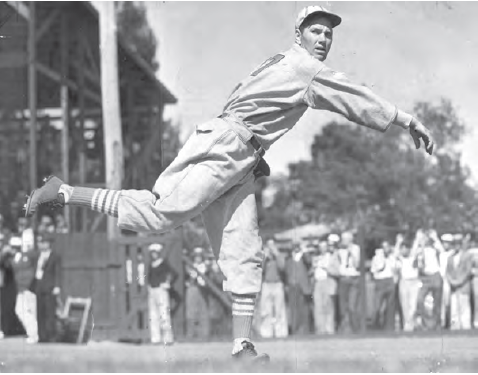

The pitching match-up favored the Cardinals. Baseball’s best-known hurler faced the major-leagues’ lowest scoring team. Eccentric, colorful, and given to fits of braggadocio in his down-home Arkansas drawl, the 24-year-old Dizzy Dean was one the sport’s biggest drawing cards in just his third full season. He had won 20 games the previous campaign and entered this contest with a 12-3 slate to push his career record to 51-36. Dean’s mound opponent was a 26-year-old southpaw swingman acquired in the offseason from the St. Paul Saints of the American Association, Tony Freitas. The three-year veteran with a 17-12 record (3-3 thus far in ’34) was charged with subduing the NL’s highest-scoring offense and extending the Reds winning streak to three games for the first time all season.

As the Great Depression tightened its grip on America, 12,000 spectators found an afternoon of diversion at Crosley Field. That crowd, almost five times the season average of 2,651, was a “tribute to the sport and the loyalty of the patient fans of Redland,” opined Ryder.2 They’d get their money’s worth.

The game unfolded as a hitless affair until the fourth when Frisch singled to drive in Pepper Martin, who had walked. Thirty-eight more hits would follow before the game was decided. Ernie Lombardi’s grounder to plate Chick Hafey tied the game in the bottom of the fourth. The seesaw battle was just getting underway. The lowly Reds smacked Dean around in the fifth, taking the lead, 3-1, with two outs on a, RBI single by Gordon Slade, who later scored on Mark Koenig’s triple. The rough-and-tumble Gas House Gang wasted no time in tying the game, scoring twice in the top of the sixth. Martin led off with a single, swiped third, and scored on Frisch’s double; Ripper Collins drove in the Fordham Flash with a single.

Looking like anything but the hurler who had won 11 of his last 12 decisions, Dean was wild and battered. In the sixth he loaded the bases with no outs on a walk, single, and his late throw to second on a fielder’s choice. Dizzy worked enough magic to escape the with just one run, but squandered the lead, 4-3. True to the script of the game, the Redbirds tied the game in the top of the next frame when Martin’s sacrifice fly drove in Chick Fullis.

Dean was shaky again in the seventh. Koenig doubled and scored on Hafey’s single to put the Reds back in front, 5-4. Dean surrendered his ninth hit in the last four innings, a single to catcher Lombardi, but extricated himself from another mess. He threw the equivalent of a regulation shutout before the Reds tallied another run.

Luck was on the Cardinals’ side in the ninth. Fullis hit a lazy blooper to center field, just out of Hafey’s reach. The ball rolled away and Fullis had a leadoff double. Leo Durocher’s single tied the game.

Beaten up yet still standing, Freitas was on the mound for the Reds when the game went into extra innings. In three of the next four innings, the Redbirds had a runner on third base, yet came up empty each time. In the 10th, Frisch led off with a single and moved to third with one out. Ripper Collins, the team’s most feared slugger, who would go on to led the NL in home runs (35) and slugging (.615) in ’34, hit into an inning-ending double play to third; first baseman Jimmy Shevlin’s strike to Lombardi erased a sliding Frisch at home plate. The Cardinals loaded the bases in the 12th on consecutive singles and an intentional walk, then Ducky Medwick, mired in an 0-for-16 slump, hit a weak roller to Freitas, who initiated a dramatic 1-2-3 inning-ending double play. An inning later, Collins reached third on Burgess Whitehead’s double, but was stranded.

The Reds’ best chance to end the game came in the 16th. One might wonder amusingly how Dean, who later parlayed his fame on the diamond into an equally famous career as a broadcaster, would have announced the frame. Slade and Koenig led off with singles and moved up a station on Hafey’s bunt. An outfield fly away from a loss, Dean intentionally walked Shevlin to set up a play at the plate. He dodged a bullet when Lombardi popped up to second, then punched out pinch-hitter Harlan Pool on a called third strike.

The 17th was the most dramatic inning of a game filled with high drama. Like most pitchers, Freitas was in uncharted territory. He had never pitched more than 10 innings in a game, and would never do so again in his five-year career. Medwick ended his slump with one emphatic swing, sending a fly to deep right field. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, the ball hit the top of the wall and caromed onto the roof of the factory across the street.3 The 22-year-old Medwick, who had just been selected to play in his first of six consecutive All-Star Games (nine in all), gave the Cardinals the lead, 6-5, but his most important play was yet to come. Like a punch-drunk heavyweight boxer, the weary Reds countered with their own run in the bottom of the frame, producing the contest’s fifth tie. Tony Piet doubled with two outs and scored on Slade’s single.

The Cardinals saw a new pitcher on the mound to start the 18th, hard-throwing Paul Derringer. [Freitas had been lifted for a pinch-hitter]. Normally a starter, Derringer was coming off a tough-luck season, losing 27 and winning just seven, though he would develop into one of the circuit’s best hurlers, winning 20 or more game four times. However, this was not an inning to remember. After Whitehead drew a one-out walk, Pat Crawford, pinch-hitting for Dizzy, singled. Two batters later, Jack Rothrock laced a two-out grounder past the shortstop to drive in Whitehead. Frisch collected his fourth hit, a liner to center, for his third RBI, plating Crawford and giving the Gas House Gang its first two-run lead of the game, 8-6.

The new Cardinals pitcher was Jim Lindsey, a little used 35-year-old right-handed mop-up artist, who began the season with the Reds. Shevlin started the Reds’ rally with a one-out single. Lombardi reached on Durocher’s error. Two batters later, Adam Comorosky drew a walk to load the bases with two outs. To the plate stepped pinch-hitter Sunny Jim Bottomley, who had enjoyed his best seasons with the Cardinals in the 1920s, including an MVP Award in 1928. Out the last four games because of an injured arm, the future Hall of Famer and team captain sent Lindsey’s offering to deep left field. Medwick raced “back toward the scoreboard like a startled hare,” wrote Ryder, “leaped high and came down with the ball.”4 His running catch saved an extra-base hit and preserved the Cardinals’ victory, 8-6, in 4 hours and 28 minutes.

Medwick’s home run and his heroic, game-saving catch made a winner out of Dean. Far from his best, Dizzy yielded 18 hits, walked seven, and fanned seven in what proved to be the longest outing in his career. His victory inaugurated one of the most spectacular stretches a pitcher (in the modern, post-1920) era had ever experienced. From July 1 through the end of the season, Dizzy went 18-4 with a 2.05 ERA, tossing a shutout on two days’ rest on the last day of the season to win his 30th game and clinch the pennant for the Redbirds. Freitas received a no-decision for his yeoman effort. Like Dean, he yielded six runs, all earned, and 17 hits, walked two and whiffed five. He remained a swingman for the Reds, posting a 6-12 slate in ’34.

Though the contestants had played the equivalent of a doubleheader, they jotted back onto the field after about a 15-minute break for the second contest of the Sunday twin bill. With the score tied, 2-2, after five complete innings, the game was called after 1 hour and 13 minutes due to darkness. “23 innings ought to be enough for the most confirmed fan,” opined the Enquirer.5

This article was published in “Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: A Gem in the Queen City” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and “Dizzy Dean’s 18-Inning Victory Keeps Cards Near Front,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 2, 1934: 1B.

Notes

1 Jack Ryder, “Reds Lose First in Eighteenth — Second Game Tie Affair,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 2, 1934: 14.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 8

Cincinnati Reds 6

18 innings

Crosley Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.