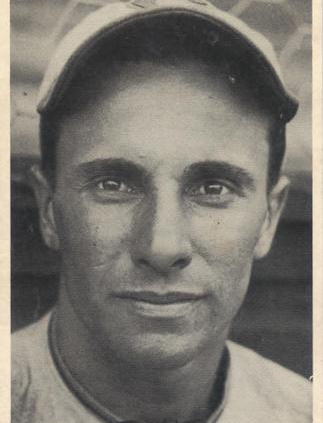

Tony Freitas

Tony Freitas, left-handed pitcher with a deceptive delivery, appeared in 107 major-league games from 1932 through 1936 as both a starter and reliever for Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics and for Charlie Dressen’s Cincinnati Reds.

Tony Freitas, left-handed pitcher with a deceptive delivery, appeared in 107 major-league games from 1932 through 1936 as both a starter and reliever for Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics and for Charlie Dressen’s Cincinnati Reds.

Freitas also had a historic minor-league career, appearing in 736 games from 1928 through 1953, mostly in the Pacific Coast League, with a record of 342 wins and 238 losses.1 He was the winningest left-handed pitcher in minor-league history and in 1984 was voted by SABR the best minor-league pitcher of all-time.2

Even with all his accomplishments, Freitas is remembered as much for his colorful personality as for his numbers. After five years in the majors and while starring for the Sacramento Solons of the PCL, Freitas was asked if he would like to return to the major leagues and pitch for the three-time world champion St. Louis Cardinals. He politely told the owner of the club, “If it’s all the same to you, Mr. Rickey, I would just as soon finish my career in the Pacific Coast League.”3

One of Freitas’s greatest thrills? “Putting on a uniform and getting paid for the game I loved to play for nothing.”4 His greatest scare? A car accident that landed him in a ditch and nearly ended his life at the age of 37.

Antonio Freitas Jr. (pronounced FRAY-tis) was born on May 5, 1908, in Mill Valley, California, across the bay from San Francisco. His parents were Antonio and Maria (née Fonseca) Freitas. Freitas’s father emigrated to California in 1888 or 1889 and his mother in 1901 from the Azores, an Atlantic island region of Portugal. They met and married in 1903 and lived in a farmhouse they built themselves with the help of friends. Freitas’s father was superintendent of Mill Valley’s street sweepers when he retired in 1927.5 “Good enough job to support a family,” Freitas said.6 His mother did not work outside the home.

Freitas – who had three older siblings, George, Alice, and John – attended Tamalpais Union High School for three years. After he graduated, and later during his baseball offseasons, Freitas worked as a machinist (a skill he learned in high school), a carpenter, and other odd jobs.

Freitas’s father allowed him to play baseball in high school only after Freitas’s brothers promised to cover his chores.7 A left-handed second baseman initially (he batted righty), Freitas pitched for Tamalpais in 1925 and 1926. After high school, he played for the Mill Valley Merchants in the San Francisco semipro Winter League.

On April 6, 1926, the Pacific Coast League – Class AA, the highest level of minor-league baseball at the time – welcomed the San Francisco Missions as the second club in San Francisco (the other was the Seals).8 One of the team’s executives, Howard Lorenz, pressed Freitas to join the Missions, but the 18-year-old rejected the idea.9 One year later, Tommy Bickerstaff, local ballplayer and duck-hunting buddy of Buddy Ryan, the manager of the PCL’s Sacramento Senators, arranged a tryout for Freitas with Ryan. Perhaps by then Freitas was drawn to the growing allure of the PCL and the attention generated by Lou Gehrig’s and Babe Ruth’s California barnstorming tour in October of 1927.

Ryan signed Freitas and optioned him to the Arizona State League (Class D), where in 1928 Freitas pitched for the Phoenix Senators. In 1929, between brief stints with Sacramento, he was with the Bears in Globe, Arizona.

In 1930 Freitas began the season with Sacramento. In his first nine starts, he tallied seven wins without a loss, en route to 19 on the season. On June 10, 1930, Moreing Field – the Senators’ home field – hosted the first game in PCL history under the lights. With the stadium lights on again the next night, Freitas took the mound and suffered his first loss of the season when he gave up five runs to the Oaks in the final two innings. “And don’t blame the damn lights!” Freitas joked.10

That game also featured a brouhaha that involved Freitas and led to umpire Chet Chadbourne’s inglorious baseball moment. Freitas was the runner on third base when Jim McLaughlin hit a comebacker to the pitcher. The nimble Freitas escaped the ensuing rundown but wound up on third along with the trailing-runner, Ray French. Oaks catcher Ernie Lombardi tagged French for the out as Freitas alertly dashed to the unoccupied home plate.11 Oakland’s Buzz Arlett was ejected by Chadbourne for disputing the call. The next night, Arlett was again ejected by Chadbourne. When Arlett approached Chadbourne after the game for an explanation, the umpire struck Arlett with his iron face mask, sending Arlett to the hospital with a bloody noggin.12

Freitas’s personality was generally reserved, shaped by Old World virtues. “I never drank. I never smoked . . . I never [even] threw real hard,” he said.13 In one regard, however, Freitas was less restrained – he liked driving fast. The Sacramento Bee called him “a maniac of the highways.”14 On Christmas Day 1930, visiting his folks during the offseason, Freitas was arrested for reckless driving near Sausalito and assessed a $20 fine by Judge Helmore. On January 1, he was “pinched” for speeding again.15 Helmore was not amused. After Freitas made good on the $20 he had not yet paid, the judge ordered him to spend five nights in jail and revoked his driver’s license for 60 days.16

In August 1931, Freitas was at it again. He was stopped in Novato, California, for traveling 55 mph, nearly top speed for his 1928 Model A roadster. Judge Rudolff sentenced him to serve five days in jail. However, manager Ryan knew that several scouts were waiting to see Freitas pitch against the Missions. He and Freitas persuaded Sheriff Sellmer to allow Freitas to go to San Francisco with a deputy sheriff escort.17 Freitas pitched a complete game, collected two hits, and knocked in the final run in a 5-3 Senators’ victory. After the game, he stopped and ate a home-cooked dinner with his mother and dad – and the deputy – before returning to jail.18

Freitas led the Senators’ staff in 1931 with a 19-13 record. His fastball was not high velocity, and he had three slower pitches besides. He threw overhand, side-arm, semi-side, and underhand. He worked quickly between pitches. Freitas’s forte was deception and control.19

Rounding out his tools, Freitas was also a good fielder – “one of the greatest fielding moundsmen who has ever been in the coast league,” claimed the Sacramento Bee.20 He once struck out Henry “Prince” Oana of the San Francisco Seals, but when the catcher dropped the ball and could not find it, Freitas darted in from the mound, scooped up the loose ball, and threw Oana out at first.

Freitas met his future wife, Lillian (“Billie”) Armstrong – a native of San Luis Obispo, California, and a waitress in Sacramento21 – when he played for the Senators. They married in a private ceremony in Reno, Nevada, at the close of 1931, so secret that neither his parents nor his team were aware. “The only time I hear from Freitas is when he’s in jail for speeding,” said Lew Moreing, the owner of the team.22

In the 1930s, minor-league club owners sold their stars to major-league clubs to help offset declining revenues. The buzz for Freitas started when the scouts saw him twirl his gem against the Missions the night he was released from jail. Moreing rejected offers of $15,000, $20,000, and $25,000 for Freitas.23 Observers speculated that bids were not higher because Freitas’s small stature, low pitch velocity, and heavy foot when driving presented too much risk.24 (Freitas was either “little” and “tiny,” or “husky” and “stocky,” listed at anywhere from 5-feet-8 and 155 pounds, to 5-feet-6 and 170 pounds, depending on the year and the sportswriter.) Freitas proved the skeptics wrong.

On May 5, 1932, his 24th birthday, Freitas pitched a no-hitter and defeated Oakland, 2-0. 25

Fourteen days later, he tallied 11 Ks as Sacramento downed Portland (Oregon), 6-4.26 Philadelphia’s Connie Mack jumped into action. On May 20, he traded Jimmie DeShong and paid $35,000 to get Freitas.27 The “little Portuguese portsider” was finally on his way to the big leagues.28

On May 31, 1932, at Shibe Park, Freitas was the starting pitcher against the second-place Washington Senators. “I was scared stiff,” he recalled.29 Through the first seven innings, Philadelphia led, 3-1, until Freitas allowed a run in the eighth and another in the ninth. When he was removed for a pinch-hitter in the tenth, Freitas had given up only three hits. Future Hall of Famer Heinie Manush – whom Freitas had retired four times that game – tripled off veteran George Earnshaw in the top of the 12th inning and Washington won, 5-4.

Freitas lost his next two outings, one of which was to the New York Yankees. In the top of the first inning, Freitas struck out Babe Ruth, one of Freitas’s all-time thrills. A year later Ruth homered off Freitas at Yankee Stadium.30 That home run, Freitas told his great-nephew, traveled about 900 feet.31

After his rocky start in 1932, Freitas racked up 10 consecutive victories from June 11 through August 25, nine of which were complete games, including one shutout. In the one game he did not finish, Freitas fielded a comebacker with runners on second and third. He ran at the St. Louis Browns’ Jim Levey and tagged him out as Levey retreated to third, then Freitas bolted after George Blaeholder and tagged him out just as Blaeholder dove back into second. Freitas got the unassisted double play – a rare feat for a pitcher – but fell over Blaeholder and got spiked in the ankle. Freitas left the game, received three stitches, and missed his next two starts.32

The Yankees’ ace in the 1930s was Hall of Famer Lefty Gomez, also a San Francisco Bay area native. When they were teenagers, Freitas pitched against Gomez in a semipro game at Boyle Park in Mill Valley.33 The two started against each other on two occasions in the majors.34 On both occasions, Freitas left the game with a lead that Philadelphia’s bullpen did not hold.

Freitas finished the 1932 season with a .706 win-loss percentage (12-5) and a 3.83 ERA; only Lefty Grove finished ahead of “Little Tony” in those categories for the A’s. “He isn’t an impressive player to look at, but on the mound, he is one of the smartest I ever knew,” proclaimed Mack, his skipper.35

Following his excellent rookie season, Freitas did not appreciate that Mack proposed a pay cut – a result of budget constraints amid the Depression, claimed Mack. Freitas refrained from signing but said nothing to the press for fear of sounding unflattering toward Mack. Before spring training, Mack revised his proposal to match Freitas’s rookie salary of $1,000 per month for seven months, and Freitas reluctantly signed. According to writer Art Hill, at that pay rate, Freitas had to “hustle a lunch pail during the winter.”36

After a disappointing 2-4 start to the 1933 season, Freitas was optioned to Portland in the PCL in late July. Freitas admitted that he had a little arm trouble,37 but he claimed that the real problem was the muggy climate in the East – he could not sleep, or he woke up “drenched in perspiration. . . That took all of the sap out of me,” he explained.38 He turned things around in Portland and was recalled by Philadelphia, only to be traded in November to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association (Class AA).

The following spring, the Cincinnati Reds, a club that had not finished out of the second division since 1926, acquired Freitas for a package consisting of pitcher Jim Lindsey, outfielder Ivey Shiver, and $17,500. While with the Reds, Freitas pitched his most memorable game in the majors. On July 1, 1934, he and Dizzy Dean of St. Louis each pitched 17 innings in a game won by the Cardinals in the 18th when ace Paul Derringer relieved Freitas and allowed two runs for the 8-6 loss.39 “I lost nine pounds that day. And I didn’t have nine pounds to lose,” Freitas said.40 In the game, Freitas swatted three hits in seven at-bats off Dean. It was his best offensive output in the majors since the game he pitched against the St. Louis Browns during the 1932 10-win streak, in which he collected one hit and three walks with three runs scored.41

The first night game in major-league history took place on May 24, 1935, in Cincinnati. Freitas pitched his only major-league night game on July 31, 1935, a 10-inning complete game victory over the defending world champion St. Louis Cardinals, 4-3. The game was made famous when nightclub entertainer Kitty Burke grabbed a bat and hit the ball to pitcher Paul Dean, which she boasted distinguished her as the first woman to have an at-bat in a big-league game.

Freitas compiled a 6-12 record in his first year with the Reds and a 5-10 record in 1935. He pitched well in games he started and won – a 2.20 ERA in five complete-game wins in 1934 and a 1.76 ERA in five route-going wins in 1935. However, he did not lift himself out of the back end of the Reds’ rotation with his other appearances.

Freitas injured his elbow during a game he lost on May 3, 1936.42 Four weeks later, he appeared in his final big-league game; he pitched to one batter, pinch-hitter Johnny Mize, whom he walked in the eighth inning. It was back to the minors for Freitas. Cardinals business manager Branch Rickey and Larry MacPhail, vice-president and GM of the Reds, cobbled together a three-team deal, sending Freitas to Columbus in the American Association (Class AA). Columbus pitcher Bill Cox went to the Cardinals and Cards pitcher “Wild Bill” Hallahan to the Reds. Before he left St. Louis, however, Freitas wanted to make an amendment to the deal. Actually, “it was my wife’s idea,” he admitted.43

Freitas knew that St. Louis owned both the Columbus and Sacramento teams – Rickey had bought the Senators from Moreing in the 1935-36 offseason – so the Californian visited his new boss and asked if he could be sent to Sacramento rather than Columbus. Rickey agreed and made it happen the following spring.

Freitas won 23 games during the 1937 season for the Solons (Sacramento’s new name after Rickey bought them). The club finished in first during the regular season, and “no one was more important to [Sacramento’s] winning formula than [the] stylish left-hander from Mill Valley.”44 However, the San Diego Padres swept Sacramento in the first round under the new Shaughnessy Playoff Plan.45 San Diego’s regular-season home run leader, Ted Williams, homered off Freitas in the series clincher. The Padres then swept Portland in the final round, and they were named the league champion, not the Solons.

In 1938, Freitas won 24 games, falling short of the league-leading 25 games won by19-year-old Fred Hutchinson, the Seattle hurler whom the Sporting News named as the best minor-league player of 1938. Sacramento finished in third place but won the playoffs. Freitas had two complete-game victories in the semifinal round and two more in the finals.46 In Game Four of the final round against San Francisco, Freitas gave up only one run in 10 innings. The Solons won the next game to take the series. Disheartening to Sacramento, however, the PCL changed the rule again and named the regular season’s pennant winner, the Los Angeles Angels, champion – not the playoff victor, the Solons.

Freitas’s fine performance in the 1938 season prompted Rickey to ask the hurler how he would feel about coming back to the big leagues. St. Louis had won the World Series in 1934 but by 1938 had slipped to sixth place. The Redbirds’ offense looked solid for 1939, but they needed more pitching.47

But Freitas felt settled in Sacramento with his wife and son.48 He liked the limited travel and the West Coast weather. He had already experienced the thrill of pitching in the majors. He was good enough to be the Opening Day pitcher on two different clubs – 1933 for Philadelphia and 1935 for Cincinnati. (He lost both times.) However, his stat line after five years in the majors was pedestrian at best – 25 wins, 33 losses, and a 4.48 ERA over 518 innings total.

By comparison, over his first six seasons in Sacramento (1929-32 and 1937-38), Freitas had 93 wins, 50 losses, and a 3.15 ERA. He had two 20-win seasons in 1937 and 1938 and, although he did not know it at the time, he would go on to have four more 20-win seasons with Sacramento in 1939 through 1942. He averaged just over 306 innings per year from 1937 through 1942.

Freitas knew just how difficult it was to pitch in the majors as compared to the minors. He told Dennis Cusick of the Sacramento Bee, with a not quite straight face: “The only fella that wasn’t a good hitter is the fella that walked up to the plate without a bat. I could get him out.”49

Sacramento was in pennant contention every year Freitas played there, and Freitas’s salary plus playoff bonuses made his income comparable to what it would have been in the majors.

Freitas processed all these thoughts in a short time and declined Rickey’s offer.

The southpaw continued his exceptional pitching in 1939 and led the PCL with 30 complete games and nine shutouts. He had 21 wins, followed by 20 wins in 1940 and 21 in 1941 for Sacramento. He was the honoree at “Tony Freitas Night” on August 22, 1941.50

In the 1941 playoffs, Sacramento got by San Diego but lost to Seattle in seven games. In the San Diego series, Freitas defeated minor-league legend William Clinton (“Bill”) Thomas in Game Three, 3-2 – the only postseason game in which these two minor-league greats faced each other.51 Thomas, the winningest pitcher in minor-league history with 383, pitched in over 1,000 professional games but never pitched in the majors.

Freitas grabbed the golden ring in 1942. Sacramento was four games out of first place with five games left to play, all against the league-leading Los Angeles Angels. The Solons came from behind to win on Thursday, September 17, and Freitas coasted to his 23rd win of the season on Friday. On Saturday, Gene Lillard – a late-season pickup from Rochester – smacked a pinch-hit, two-run homer to give the Solons the victory in the 11th inning, 6-5. “Every move that [manager] Pepper Martin made turned out to be perfect,” said Freitas.52

Sunday, September 20, was Freitas’s day. Martin called on Freitas to pitch the ninth inning in the matinee on one day’s rest. He retired the Angels in order and locked down the Solons’ come-from-behind win, 7-5. Then Freitas came right back in the nightcap and pitched a four-hit, seven-inning complete game victory, 5-1, for his 24th win of the season – his sixth consecutive 20-win season. Freitas could have been elected Sacramento’s mayor on the spot.53 The “Martinmen” were undisputed PCL champs for the first time in club history.54

An arm-weary Freitas lasted only three innings in Game Four of the first round of the 1942 playoffs; the tired Solons were eliminated in five games. That week, Freitas enlisted in the US Army Air Forces (renamed from the US Army Air Corps in 1941) and served for 37 months until October 1945. He was an aviation mechanic stationed at Mather Field in California before he was transferred in November 1943 to Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base in Houston, Texas.55 Freitas was also deployed overseas for a couple of months in the US territories of Saipan and Guam.

While in the service, Freitas took over as manager of the Ellington Field baseball team. One of his first managerial moves was to bench third baseman Col. Charles Chitty, who, according to his obituary, attended two colleges on baseball scholarships.56 According to Freitas, “He was no more a ballplayer than you could throw a stick at.”57 Chitty quit. When Freitas was informed that his team now had to take a bus and not a plane to its away games, he learned that Colonel Chitty did not like taking orders from a corporal.

While on leave six months before his scheduled discharge, Freitas drove 52 hours non-stop from Texas to California to see Billie. Near Lodi, California – less than an hour from his home – Freitas passed out and ran his car off the road. He suffered a broken nose and collarbone.58

“I woke up underneath my Model A,” he recalled, “in the bottom of a ditch that had been full of water for irrigation all the time. This day it was dry.” Freitas paused. “You think we’re not here in a blueprint? You better believe it, man.”59

Freitas returned to Sacramento (which was by then classified as Class AAA and no longer affiliated with the Cardinals) in 1946. Although Freitas led the Solons with a minor-league career-best 2.34 ERA, he finished with a 16-20 record, breaking his string of 20-win seasons.

Freitas did not mention his injury when he told biographer Tony Salin, “I never did get back to form [after the service].”60 In 1947 his record slipped to 13-17; in 1948, 12-11; in 1949, 4-4; and in 1950, 0-1.

Freitas was released on May 16, 1950, ending his splendid run in Sacramento. Over his 15-year PCL career, Freitas won 228 games, all but four with Sacramento.61 To honor him, the team retired his number 17.62

The next day, Freitas turned down an offer from the Marysville Giants, a semipro team in the Sacramento Valley League, and instead signed with the Modesto Reds in the California League (Class C).63 He won his first game with Modesto on May 21 – two days before Sacramento dignitaries, Solons brass, and 4,501 fans got the chance to thank him. “Respected by friend and competitor alike,” said master of ceremonies Albert Sheets.64 Among the many gifts Freitas received upon his departure from Sacramento was a new rifle.65 Hunting, fishing, and playing the accordion always were Freitas’s hobbies.66

Freitas was happy – mentoring his teammates while pranking both them and his manager67; instructing at youth baseball clinics68; and coaching from the third base box when he wasn’t pitching (it was easier to banter with the fans from there than from the dugout). With Modesto as with Sacramento, Freitas helped put fannies in the seats.

By season’s end, his record was 20-6; his 2.56 ERA led the league. He was named to the California League All-Star team.69 In the postseason, Freitas won three games in the playoffs, including a complete game 11-inning five-hitter over the Stockton Ports in the deciding game.

The Vancouver Capilanos in the Western International League (Class A) drafted Freitas over the winter.70 But Modesto convinced him to stay and be their player-manager for the 1951 season. Although he was the oldest hurler on the staff by 10 years, and a grandpa, Freitas led the league with 25 wins and 28 complete games (two of which were shutouts), and his 2.99 ERA was a team-best. He repeated as a Cal League All-Star.71

On January 29, 1952, Modesto released Freitas. “I was getting too much money,” Freitas explained. “Seven hundred dollars a month.” Others were getting just $200-300 a month.72 The Stockton Ports, a St. Louis Browns affiliate also in the California League, picked him up. Freitas led the team with an 18-13 record and 24 complete games. His seven shutouts were a new league record.73 (Mark Ferguson broke the record with eight in 1982.74) At the plate, the wily veteran walked more times (6) than he struck out (2) and stole two bases!

When Harry Clements took ill in the middle of the 1952 season, Freitas served as the interim manager until former major-leaguer Bill Salkeld took over for the 1953 season. At 45 and 20 years older than any of his teammates not named Clements or Salkeld, Freitas led the league with 279 innings (tied with Tony Ponce), 28 complete games (including three shutouts), and 22 wins. The latter gave him nine 20-win seasons, tying the minor-league record set by Charles “Spider” Baum in 1917.

On September 11, the Stockton fans presented Freitas with a brand new car, a 1953 Ford, before he hurled a five-hit shutout to move the Ports past Bakersfield into the playoff finals.75 A humbled Freitas said, “This is the greatest thrill in my career.”76

Freitas’s playing career ended after that final series. His 342 minor-league victories placed him fourth behind Bill Thomas (383), Joe Martina (349), and George Payne (348). The three of them were right-handed pitchers, so Freitas’s 342 wins made him the winningest left-handed pitcher in the minors. Freitas had more major-league victories than the other three combined.77

In 1954, the Solons invited Freitas back to coach, not pitch, for manager Gene Desautels. When Desautels resigned suddenly on July 12, 1954, Freitas agreed to manage. It seemed a good fit, with Freitas’s experience and personality. However, the Solons finished in seventh place in 1954 and eighth in 1955 and Freitas was released on October 27, 1955. Freitas later acknowledged that he “was never cut out to be a manager” – he didn’t have the right “disposition,” he said.78

When his baseball career was over, Freitas took various jobs, mostly in sales – cars for Mr. Newton Cope, furniture at Breuner’s.79 But those did not last long. He landed work as a rocket control mechanic at Aerojet, a rocket propulsion manufacturer in Rancho Cordova (near Sacramento) from 1956 to 1970. After that, Freitas and his wife moved to Los Osos on Morro Bay. In 1980, they moved back to the Sacramento area, the place of his fondest baseball memories.80

Billie Freitas died on July 5, 1986, at the age of 77. They had been married 55 years. Tony died on March 14, 1994, of an apparent heart attack while doing yardwork.81 He was 85 years old.82

Freitas was inducted into the Sacramento Athletic Hall of Fame on May 24, 1969. The great Bob Feller was the keynote speaker at his banquet.83 On February 9, 1970, the La Salle Club/Sacramento Hall of Fame bestowed the same honor on the former Solon.84 And in 2003, Freitas was elected into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame.85 He is a member of the PCL’s All-Century Team.86

Sources and acknowledgments

Special thanks to SABR member and author Zak Ford for sharing his unpublished research on Freitas; to Freitas’s great-nephew Michael Avella for his time, memories, and a copy of his videotaped interview of Freitas; and to Cassidy Lent, manager of reference services at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, for supplying copies of news clippings from the Freitas files in Cooperstown.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Lloyd Johnson (Ed.), The Minor League Register (First Edition) (Durham NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1994); . Other publications and online databases have various different won-lost records for Freitas. The author contacted baseball-reference.com to advise that its database, which gives Freitas’s record as 342-237 in 727 games, omits nine games played and one loss suffered with Sacramento in 1950. See, e.g., Tom Kane, “Tony Freitas, Veteran Solon Pitching Star, Is Handed Release,” Sacramento Bee, May 16. 1950: 24. B-R replied that “[B-R’s] process for reviewing historical minor league data is to work through each league-season systemically [sic]. They have written up a summary of their working methods here, which may be of interest: https://www.chadwick-bureau.com/doc/historical/. This is a very active area of research, so coverage of this era should be much more complete over the coming few years.” (Aidan Jackson-Evans, Sports Reference, LLC, personal communications [via e-mail], January 3, 2024.)

2 The Society for American Baseball Research (Ed.), Minor League Baseball Stars, vol. II (1985), 9-14. [All three volumes are available online at https://profile.sabr.org/page/research-resources.] In the same poll, Buzz Arlett was voted the outstanding player in minor league history.

3 Tony Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes (Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC/Contemporary Publishing Group, 1999), 96.

4 Interview of Tony Freitas conducted by his great-nephew Mike Avella and others on May 5, 1993 [unpublished personal video tape recording, shared with the author on May 6, 2024] – hereafter, the “1993 Avella tape” – @1:28:21.

5 According to their obituaries, they were married for 50 years when his father died on February 22, 1954, at age 87; his mother died on June 20, 1964, at age 84. Antonio S. Freitas Obituary, San Rafael Independent Journal, February 24, 1954: 2; Mary Freitas Obituary, San Rafael Independent Journal, June 22, 1964: 4.

6 R.A. Cabral, (2019). “Portugee [sic] Portsider Leads Solons.” RACABRAL.com. https://www.racabral.com/ss-portugee-portsider.

7 Independent News Service, “Brothers Helped Tony,” Pasadena Post, June 15, 1933: 11.

8 Abe Kemp, “Coast League Flag Race On Today,” San Francisco Examiner, April 6, 1926: P-1.

9 1993 Avella tape @29:39.

10 Cabral, “Portugee Portsider Leads Solons.”

11 “Freitas in First Loss of Season,” Sacramento Bee, June 12, 1930: 22.

12 Rudy Hickey, “Arlett Plans to Take Action for Blow by Umpire,” Sacramento Bee, June 13, 1930: 1.

13 Tony Freitas, “Interview of Tony Freitas by Dennis Cusick” conducted on May 20, 1987 [tape recording]. California Revealed from Center for Sacramento History (University of California: Calisphere). Retrieved April 30 2024, from https://calisphere.org/item/414e3e5a05ff5bb326710febf18e526f/) – hereafter, the “1987 Cusick interview” – tape#2 @30:10.

14 Rudy Hickey, “Tony Freitas Released from Jail to Pitch for Scouts at Bay To-Night,” Sacramento Bee, August 20, 1931: 18.

15 Associated Press, “Tony Freitas, Sacs Hurler, Again Pinched for Speeding,” San Bernardino County Sun, January 13, 1931: 14.

16 “Freitas Fans Out in Court,” Santa Rosa (California) Republican, January 13, 1931: 5;

17 Rudy Hickey, “Braves Interested in Freitas and Hack But Not in Buying Senators,” Sacramento Bee, August 19, 1931: 18; “Tony Freitas Jailed 5 Days for Speeding 55 Miles in Novato,” San Francisco Examiner, August 20, 1931: 25; Associated Press, “Sheriff Relents; Freitas Gets Out to Twirl Tonight,” Stockton (California) Daily Evening Record, August 20, 1931: 21.

18 1993 Avella tape @11:48.

19 Associated Press, “Globe Bears Beat Tucson,” The Daily Arizona Silver Belt, June 7, 1929: 2; Russell J. Newland, “Scouting Western Sports,” Ventura (California) Free Press, August 20, 1931: 5; Associated Press, “Tony Freitas Is Colorful Player,” Bluefield (West Virginia) Daily Telegraph, June 29, 1932: 8.

20 Rudy Hickey, “Night Game’s Opening Brings Out Best Crowd Since Season’s Start,” Sacramento Bee, May 13, 1931: 24.

21 Lillian ‘Billie’ Freitas Obituary, Sacramento Bee, July 9, 1986: B2.

22 “Tony Freitas Believed Wedded to Local Girl; Confirmation Lacking,” Sacramento Union, January 5, 1932: 6; “Marriage Licenses,” Nevada State Journal, January 5, 1932: 4.

23 “Moreing Turns Down Cubs on Bid for Tony Freitas,” Sacramento Bee, March 24, 1932: 18; Abe Kemp, “Pitcher Will Report to A’s Immediately,” San Francisco Examiner, May 21, 1932: 15; Dennis Cusick, “Sacramento’s Pitcher of Success,” Sacramento Bee Sunday Magazine, August 9, 1987: 7.

24 Cusick, “Sacramento’s Pitcher of Succes”: 6-7.

25 “Only Two Oaks Reach First in No-Hit Game Hurled by Tony Freitas,” Sacramento Bee, May 6, 1932: 30.

26 “Freitas’ Win Over Tribe Makes Tony Only Victor in Ten Senatorial Games,” Sacramento Bee, May 20, 1932: 26.

27 Associated Press, “Birds Sell Freitas to Coast Club,” Logan (Ohio) Daily News, September 15, 1936: 3.

28 The first use of this nickname for Tony Freitas appears in Pacific Coast News Service, “Tony Freitas of Oakland Sacs’ Hero,” Oakland (California) Post-Enquirer, April 19, 1930: 23. It appeared in newspapers across the country after that, often used by Bill Conlin, long-time beat writer for The Sacramento Union and The Sacramento Bee. Conlin also hung the “gutta percha man” nickname on Freitas, which was “a high compliment in the 1940s. Gutta percha was a natural rubber that was used in golf balls in the 1930s and revolutionized the game of golf. Conlin considered Tony’s well used pitching arm to have the same elastic properties.” Alan O’Connor, Gold on the Diamond: 1886 to 1976 (Sacramento, California: Big Tomato Press, 2008), 156.

29 Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 93.

30 The A’s were down, 14-11, in the eighth inning when Ruth hit a three-run home run to deep rightfield off Freitas who had come on in relief. Freitas faced Ruth 14 times, surrendering four hits (three singles and that home run) and three walks, but he struck out the Bambino three times, tying Pepper Martin of the Cardinals, Freitas’s future manager in Sacramento, as the batters Freitas struck out the most in the majors.

31 Michael Avella (2023). Loved going to my great Uncle Tony’s house in Orangevale and hearing all kinds of baseball stories [Facebook comment]. Re: Tony Freitas, Marin’s Greatest Baseball Player? (July 1, 2021). Sausalito Portuguese Cultural Center [Facebook page], accessed April 26, 2024 from https://www.facebook.com/idesst/photos/a.144609632250720/4371925492852425/?type=3.

32James C. Isaminger, “Tony Freitas Makes 2 Killings Unaided,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1932: 14.

33 1993 Avella tape @1:13:10.

34 September 22, 1932, and June 8, 1933.

35 George A. Barton, “Sportographs: Connie Mack Praises Tony Freitas,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 3, 1932: 16.

36 Art Hill, I Don’t Care If I Never Come Back (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 113.

37 Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 94.

38 John J. Peri, “In Between Peri-Graphs,” Stockton (California) Daily Evening Record, August 5, 1933: 9.

39 The major-league record belongs to Leon Cadore of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Joe Oeschger of the Boston Braves. They each pitched of 26 innings on May 1, 1920.

40 Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 95.

41 In Freitas’s best game in the minors, on May 31, 1938, he had three of his team’s five hits, including a double, and scored the only run in a 2-1 game that Sacramento lost to San Diego. Dominick Dallessandro – the hitter that Freitas claimed was the toughest for him to get out – hit a two-run homer to spoil Freitas’s fine pitching performance. See “Tony Freitas,” Interview by Gerald Tomlinson, n.d. [Tape recording]. Oral History Collection, Society of American Baseball Research. Retrieved April 30 2024, from https://sabr.org/interview/tony-freitas-unknown.

42 Jack Ryder, “Derringer is Knocked Out and Freitas Injured – Many Red Hits Wasted,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 4, 1936: 14,15.

43 Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 96.

44 Paul Zingg and Mark D. Medeiros, Runs, Hits, and an Era: The Pacific Coast League, 1903-58 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 78.

45 In 1936, to generate additional income during the Depression, the PCL introduced a two-round playoff (the four teams with the best regular season records) to replace the one-round playoff used in 1935 (first-half winner vs. second-half winner).

46 Postseason wins did not count in Freitas’s career totals.

47 Rickey traded Dizzy Dean, who injured his arm in 1937, before the 1938 season began.

48 Billie had a young son, Jack, when they married. The three lived in Sacramento except for the months when Freitas played elsewhere.

49 1987 Cusick interview, tape#1 @27:38.

50 “Freitas Night,” Sacramento Bee, August 22, 1941: 12. Freitas was frequently celebrated, starting with Mill Valley’s “Tony Freitas Day” on November 3, 1935. See James J. Nealon, “Rolph Playground Closing Hurts Mission Youngsters,” San Francisco Examiner, November 12, 1935: 22.

51 Donald R. Wells, The Race for the Governor’s Cup: The Pacific Coast League Playoffs, 1936-1954 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000), 139. The number of regular-season games in which Freitas and Thomas faced each other has not been determined. To be clear, no known rivalry nor jealousy existed between the two; the statistical tallies that forever links them were not assembled until the 1980s. Yet, to realize that these two record holders often went head-to-head in their race to the summit is intriguing. That is what makes the next tidbit even more entertaining. In a March 17, 1940, pre-season game, Freitas homered off Thomas (then pitching for Portland), one of only two home runs Freitas – a sub-.200 lifetime batter – hit in his professional career. Both were in spring training. See “Reich’s Homer Nets Portland Win Over Solons, 5-3,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1940: 21; and, 1993 Avella tape @1:26:46.

52 1987 Cusick interview, tape#2 @17:00.

53 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, May 17, 1950: 32.

54 The Sacramento River Cats have played in the PCL since 2000; as of the date of this writing they have won five PCL championships.

55 “In the Service,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1943: 11.

56 Charles D. Chitty Jr. Obituary, Legacy Remembers, March 21, 2009, accessed May 8, 2024, from https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/name/charles-chitty-obituary?pid=178665485

57 1993 Avella tape @1:14:39.

58 “Freitas Injured in Accident,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1945: 11.

59 1993 Avella tape @1:06:29.

60 Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 99.

61 Frank Shellenback holds the PCL record with 295 victories.

62 “American Association,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1950: 34.

63 McClatchy Newspaper Service, “Modesto Signs Freitas,” Sacramento Bee, May 18, 1950: 46; “Five Player Deal of Solons, Suds Misses Fire,” Sacramento Bee, May 17, 1950: 32.

64 Tom Kane, “Sacramento Baseball Fans Bid Adieu to Tony Freitas,” Sacramento Bee, May 24. 1950: 34.

65 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1950: 34.

66 “Tony Freitas To Be on Radio,” Sacramento Bee, May 15, 1930: 27. See also “Tony Freitas, Star Hurler, To Be on Bee Radio” [with photograph], Sacramento Bee, May 14, 1930: 10.

67 “Braves Do Not Know Freitas,” Modesto Bee, August 31, 1950: 19. And then there was this: Freitas would pull out of his pocket one of those plastic replicas of dog excrement that are sold at gag gift shops and drop it on the hotel lobby floor after a dog went by. When a custodian saw it and left to get some cleaning products, Freitas picked it up, slipped it back into his pocket, and waited for the custodian to return, to the delight of the snickering onlookers. Kelsey Boltz (August 4, 2013). I caught every game that Tony pitched for Modesto in 1950 blog comment] (November 17, 2012), Re: Stories About Tony Freitas from Burly’s Baseball Musings (wordpress.com) [Web log], accessed May 13, 2024.

68 Don Slinkard, “Tips On Pitching Are Offered By Reds’ Veteran,” Modesto Bee, July 8, 1950: 15.

69 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1950: 35.

70 “Tony Freitas to Pilot Modesto,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1951: 26.

71 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1951: 50.

72 1993 Avella tape @56:40.

73 “Class C Highlights,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1952: 60.

74 The History of the California League, https://www.californialeaguehistory.com/record-book. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

75 Stockton lost the championship series to the San Jose Red Sox.

76 John Peri, “Freitas Calls Auto Award ‘Top Thrill,’” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record, September 12, 1953: 36.

77 Martina and Payne each made it to the majors for one season.

78 1993 Avella tape @1:16:52.

79 1987 Cusick interview, tape#3 @12:21.

80 At his retirement, he received a fish smoker, a telescope, and a watch. “Capital City Immortal Tony Freitas Ends 2nd Career,” Sacramento Bee, April 25, 1970: B3; Bill Conlin, “Freitases Are Back,” Sacramento Bee, May 29, 1980: E1.

81 Tony Freitas Obituary, Sacramento Bee, March 19, 1994: B5. [Some publications and online databases give Freitas’s date of death as March 13, 1994.

82 Freitas and Billie are buried in St. Mary Catholic Cemetery in Sacramento with their son Jack W. Armstrong (3/9/1923-3/23/1960). Jack was survived at death by his wife Susie and three sons, Tim, John, and Tony. Tim Armstrong (5/17/1955-10/3/2018), gifted his grandfather’s scrapbooks to SABR member Zak Ford.

83 Marco Smolich, “Tony Freitas, Debbie Take Places in Hall of Fame,” Sacramento Bee, May 25, 1969: E1.

84 Tom Kane, “La Salle Club Inducts Five in Fame Hall,” Sacramento Bee, February 10, 1970: B4.

85 Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, Baseball Almanac https://www.baseball-almanac.com/hof/Pacific_Coast_League_Hall_of_Fame.shtml, accessed June 3, 2024.

86 Alan O’Connor, Gold on the Diamond: 1886 to 1976 (Sacramento, California: Big Tomato Press, 2008), 77; John F. Green, “Dick Gyselman,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/dick-gyselman, accessed August 13, 2024. The team is Ernie Lombardi, C; Steve Bilko, 1B; Gene Mauch, 2B; Dick Gyselman, 3B; Frank Crosetti, SS; Buzz Arlett, LF; Joe DiMaggio, CF; Arnold (Jigger) Statz, RF; Dick Barrett, Doc Crandall, Tony Freitas, Sam Gibson, and Frank Shellenback, pitchers; and Lefty O’Doul, manager.

Full Name

Antonio Freitas

Born

May 5, 1908 at Mill Valley, CA (USA)

Died

March 14, 1994 at Orangevale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.