July 21, 1919: Horrified White Sox fans witness Wingfoot Express blimp disaster in Chicago

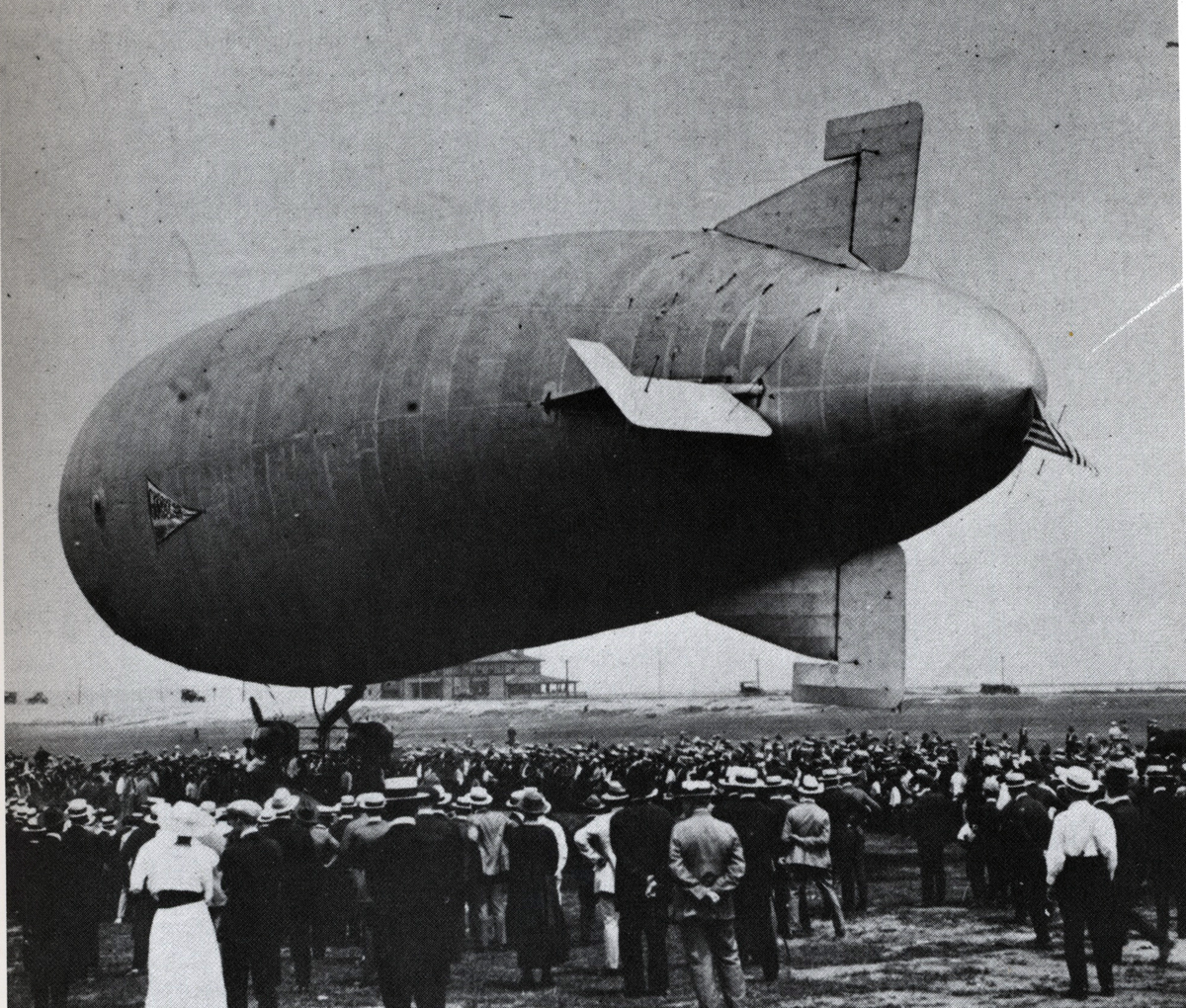

The Wingfoot Air Express lands at Grant Park in Chicago during its maiden voyage on July 21, 1919. (Photo: Chicagology.com)

It’s usually a thrill to see a Goodyear blimp flying over a sporting event. For nearly 100 years, the iconic silver airship has been observed flying over the World Series, the Super Bowl, the Olympics, and many other athletic venues around the world, providing fans with unique views from high above the playing field.

The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company’s original airship, the Wingfoot Air Express, could have become the first to pass over a baseball game when it made its maiden voyage on July 21, 1919, in Chicago. Instead, tragedy struck when the blimp exploded in midair and crashed into a crowded downtown bank, killing 13 people in America’s first civil aviation disaster. By the end of the week, however, the story had already disappeared from news pages as Chicago’s “Red Summer” erupted in a wave of death and destruction all across the city.

Before all that, the week began with a buzz as thousands of citizens flocked to the city center on a warm Monday morning to witness the strange, hydrogen-powered airship floating over their heads. The Wingfoot Express had spent all day making its way to and from Grant Park on the edge of Lake Michigan. Goodyear’s goal in sending up the blimp over one of the nation’s biggest cities was to promote what the company saw as the future of passenger air travel.

Four miles south at Comiskey Park, fans of the first-place Chicago White Sox must have been excited to see the Wingfoot Express as it began to make its way from the downtown Loop toward its final destination, the White City Amusement Park, a popular South Side entertainment center named after the 1893 world’s fair that had turned Chicago into a global entrepreneurial force.1 In 1903, a decade after the world’s fair, Wilbur and Orville Wright launched their first powered airplane flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, but aside from a handful of military pilots during World War I, few Americans had ever taken to the skies by 1919.

After being assembled at the White City aerodrome over the preceding weeks, the Wingfoot Express had taken its first two flights earlier in the day on July 21, short excursions with only the pilot, Captain Jack Boettner, and a handful of mechanics, government officials, and reporters on board for each trip. The sight of the 150-foot-long blimp overhead caused onlookers to gather on street corners across the city. At the Grant Park airstrip, thousands gathered to catch a close-up view of the Wingfoot after each landing. One final takeoff was scheduled at 4:50 p.m.; the airship was returning to its home base at White City for the night.2

By that time, 14,000 baseball fans on the South Side had seen their share of excitement from the home team, too. The White Sox rallied twice in the late innings of a doubleheader opener against their top rivals for the American League pennant, the New York Yankees, who entered the day 5½ games behind Chicago in the standings. The White Sox clinched the first game on Buck Weaver’s walk-off single in the ninth — his fourth hit –to score Nemo Leibold for a 7-6 victory. Pitcher Dickey Kerr picked up the win in relief of Lefty Williams; Kerr also started the White Sox’ winning rally by drawing a one-out walk in the ninth.3

White Sox fans in certain sections of Comiskey Park may have caught a glimpse in the distance of the Wingfoot Express on its second excursion around downtown, which lifted off about a half-hour after the game began at 2:00 p.m.4 Soon after the start of the second game, many more fans could see the blimp in the air as it began to make its way south toward the White City Amusement Park at 63rd Street. If it had finished its voyage, Goodyear’s airship likely would have passed directly over Comiskey Park around the fourth or fifth inning.

The second game finished in a similar fashion as the opener, with Shano Collins doing the honors this time with his own walk-off single in the 10th inning to score Ray Schalk for a 5-4 win. Kerr again helped out at the plate by sacrificing Schalk to second base before Collins drove him in. The rookie left-hander also picked up the victory in relief — his second of the day — thanks to two scoreless innings behind Red Faber. (Coincidentally, Faber had turned the same trick of winning two games in one day earlier that month, on July 9.)5

It was the White Sox’ third consecutive victory over the Yankees with a dramatic walk-off hit, after Shoeless Joe Jackson had ended Sunday’s series opener with a 10th-inning home run into the right-field bleachers to win it.6 The doubleheader sweep pushed the Yankees into third place, and although they avoided a sweep by winning the series finale on Tuesday, they never challenged the White Sox again as Chicago powered its way to the American League pennant and a fateful World Series.

But the mood at the end of Monday’s second game when Collins singled to beat the Yankees was decidedly downcast. Most of the crowd had left for home after witnessing a horrific tragedy in the middle of the third inning.7 As the Chicago Tribune’s James Crusinberry wrote:

“Nearly everyone at the Sox park witnessed the fate of the dirigible. The instant it caught fire, there was a scream from the fans. The game was stopped as all watched the catastrophe. It seemed the entire thing burned up in about a half minute. After that, there wasn’t much enjoyment felt over the ball games.”8

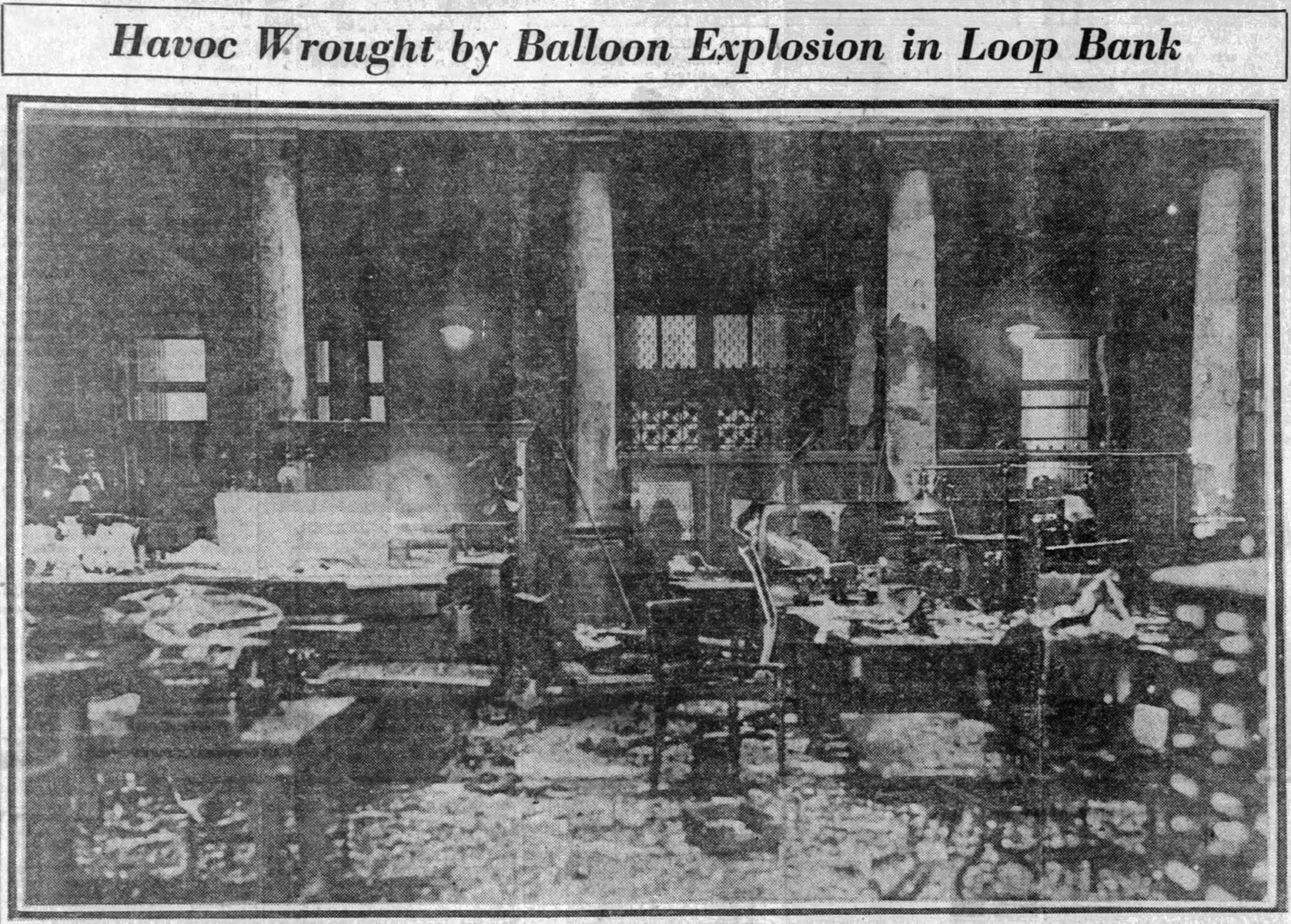

Photo from inside the Illinois Trust & Savings Bank after the Wingfoot Air Express crashed into the building, killing 13 and wounding 27 people. (Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1919)

Just minutes after takeoff, as Captain Boettner steered the Wingfoot Express one last time over the downtown Loop so the on-board photographer could take pictures of the city’s skyscrapers from above, he felt “a tremor in the fuselage, a shudder of the steel cables that held the gondola suspended beneath the blimp.”9 The airship had caught fire and was closing in on itself, rapidly descending 1,200 feet toward the ground. Boettner and the other four passengers attempted to eject with their parachutes, but only the pilot and mechanic Harry Wacker survived the fall.

The other mechanic, Carl “Buck” Weaver,10 crashed into the distinctive skylight of the Illinois Trust & Savings Bank, stunning employees working at their desks in the ornate central rotunda. The Daniel Burnham-designed building was on LaSalle Street, right in the heart of Chicago’s financial district and directly across the street from the busy Board of Trade building. Moments after Weaver’s body fell through the glass, the rest of the blimp followed, sending “fire raining down from the roof” and “an avalanche of shattered window panes and twisted iron” on everyone inside the bank.11 Ten people died and dozens more were injured by flames and debris.12

A crowd of nearly 20,000 gathered near the bank to witness the aftermath and offer help to the victims. The tragedy seemed unexplainable. As author Gary Krist wrote, “No one could quite take in the reality of what had happened. How had this experimental blimp — this enormous, floating firebomb — been allowed to fly over one of the most densely populated square miles on Earth?”13

The Wingfoot Express disaster led to sweeping changes in air safety. Within hours, Alderman Anton Cermak, Chicago’s future mayor, led an effort to pass the nation’s first air-traffic regulations, restricting flights over major population centers.14 The Grant Park airstrip was closed and Chicago began building a municipal airport — now known as Midway International Airport — just a few miles west of the White City Amusement Park. Goodyear refined its blimps to use helium instead of the more flammable hydrogen, and introduced the Pilgrim, the first modern non-rigid airship, in 1925.15 Twelve years later, the hydrogen-powered Hindenburg exploded in New Jersey and brought back memories of the Wingfoot Express.16

The White Sox concluded what had become a somber homestand at the end of the week with a loss to the St. Louis Browns on Sunday, July 27. That same day, an African-American teenager named Eugene Williams was stoned off a raft then drowned at the 29th Street Beach by an unruly mob that accused him of drifting across an invisible line in Lake Michigan that restricted black swimmers from the white-only area.17

Williams’s murder set off a week of riots, mostly instigated by roving gangs of young white men in the city’s Black Belt neighborhoods on the South Side.18 By the time the White Sox returned home in mid-August, many parts of the city were in ruins; in addition, 38 people died from the violence and more than 500 injuries were suffered in the Chicago race riots.

Sources

For an examination of Chicago’s “Red Summer” in 1919, see The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot, available online at archive.org/details/negroinchicagost00chic. Also check out the Newberry Library’s initiative, “Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots,” a yearlong project in 2019 to confront the legacy of the most violent week in Chicago history.

Additional sources not cited in the Notes include:

Chicagology.com. “Wingfoot Express.” chicagology.com/notorious-chicago/wingfootexpress

Mueller, Jim. “Blimp Has Its Ups and Downs in Early Days,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1997. chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1997-10-26-9710260142-story.html

Rovang, Dana. “Wingfoot Express Airship Disaster, Chicago 1919,” ObscureHistories.com, 2015. obscurehistories.com/wingfoot-express-airship-disaster

Box scores for the baseball games can be found at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org:

Game 1:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA191907211.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B07211CHA1919.htm

Game 2:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA191907212.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1919/B07212CHA1919.htm

Notes

1 Gary Krist, City of Scoundrels: The Twelve Days of Disaster That Gave Birth to Modern Chicago. (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012), 3. White City’s aerodrome had been leased by the US Navy during World War I, but it was the first hangar in the country to reopen for commercial enterprises.

2 Krist, 5-8.

3 James Crusinberry, “Sox Trounce Yanks Twice; Lead Flag Race by Six Laps,” Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1919: 15.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1919: 19.

5 “1919 Chicago White Sox Schedule,” Baseball-Reference.com. baseball-reference.com/teams/CHW/1919-schedule-scores.shtml.

6 James Crusinberry, “Jackson’s Homer Beats Yanks, 2-1, Before 30,000 Fans,” Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1919: 15.

7 “12 Killed, 25 Hurt When Blimp Bursts,” New York Daily News, July 22, 1919: 2.

8 “Notes,” Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1919: 15.

9 Krist, 11.

10 Carl Weaver’s nickname might have been in homage to the popular White Sox third baseman, but it’s impossible to know for sure. This author has never found a reasonable explanation for why the nickname “Buck” was attached to so many different people with the surname Weaver in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “Buck” was also a common nickname for lively and high-spirited people, and the ballplayer certainly fit that description, too. See Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952).

11 Krist, 16-17.

12 Ibid. Weaver was the only member of the airship crew to die in the crash. Two passengers also died. The 10 fatalities on the ground brought the death total to 13.

13 Ibid.

14 Krist, 119.

15 GoodyearBlimp.com. Accessed at goodyearblimp.com/relive-history on July 19, 2019. The Wingfoot Air Express disaster is not mentioned anywhere on the Goodyear Blimp website as of this writing.

16 Gary Sarnoff, “May 6, 1937: The Hindenburg Game at Ebbets Field,” SABR Games Project, sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-6-1937-hindenburg-game-ebbets-field.

17 “Bathing Beach Fight Spreads to Black Belt,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1919: 1.

18 “1919 Race Riots,” Chicagology.com, accessed online at chicagology.com/notorious-chicago/1919raceriots on July 19, 2019.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 7

New York Yankees 6

Chicago White Sox 5

New York Yankees 4

10 innings

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.