The Black Sox Scandal

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in 1919 Chicago White Sox essays

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

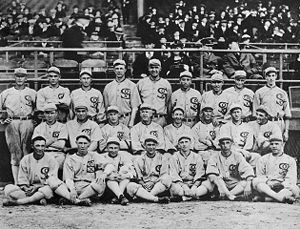

Over the decades, major-league baseball has produced a host of memorable teams, but only one infamous one — the 1919 Chicago White Sox. Almost a century after the fact, the exact details of the affair known in sports lore as the Black Sox Scandal remain murky and subject to debate. But one central and indisputable truth endures: Talented members of that White Sox club conspired with professional gamblers to rig the outcome of the 1919 World Series.

Over the decades, major-league baseball has produced a host of memorable teams, but only one infamous one — the 1919 Chicago White Sox. Almost a century after the fact, the exact details of the affair known in sports lore as the Black Sox Scandal remain murky and subject to debate. But one central and indisputable truth endures: Talented members of that White Sox club conspired with professional gamblers to rig the outcome of the 1919 World Series.

Another certainty attends the punishment imposed in the matter. The permanent banishment from the game of those players implicated in the conspiracy, while perhaps an excessive sanction in certain cases, achieved an overarching objective. Game-fixing virtually disappeared from the major-league landscape after that penalty was imposed on the Black Sox.

Something else is equally indisputable. The finality of the expulsion edict rendered by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis has not quelled the controversy surrounding the corruption of the 1919 Series. Nor has public fascination abated. To the contrary, interest in the scandal has only grown over the years, in time even spawning a publishing subgenre known as Black Sox literature. No essay-length narrative can hope to capture the entirety of events explored in the present Black Sox canon, or to address all the beliefs of individual Black Sox aficionados. The following, therefore, is no more than one man’s rendition of the scandal.

*****

The plot to transform the 1919 World Series into a gambling insiders’ windfall did not occur in a vacuum. The long-standing, often toxic relationship between baseball and gambling dates from the sport’s infancy, with game-fixing having been exposed as early as 1865. Postseason championship play was not immune to such corruption. The first modern World Series of 1903 was jeopardized by gambler attempts to bribe Boston Americans catcher Lou Criger into throwing games. Never-substantiated rumors about the integrity of play dogged a number of ensuing fall classics.

The architects of the Black Sox Scandal have never been conclusively identified. Many subscribe to the notion that the plot was originally concocted by White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil and Boston bookmaker Joseph “Sport” Sullivan. Surviving grand-jury testimony portrays Gandil and White Sox pitching staff ace Eddie Cicotte as the primary instigators of the fix. In any event, the fix plot soon embraced many other actors, both in uniform and out. Indeed, dissection of the scandal has long been complicated by its scope, for there was not a lone plot to rig the Series, but actually two or more, each with its own peculiar cast of characters.

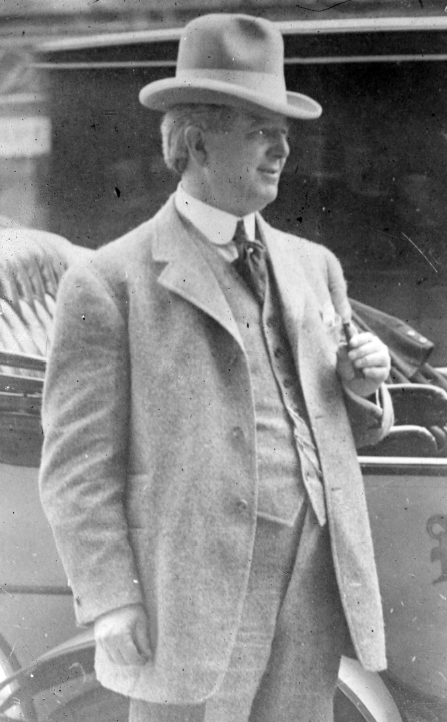

Since it was first deployed as a trial stratagem by Black Sox defense lawyers in June 1921, motivation for the Series fix has been ascribed to the miserliness of Chicago club owner Charles A. Comiskey. The assertion is specious. Comiskey paid his charges the going rate and then some. In fact, salary data recently made available establish that the 1919 Chicago White Sox had the second highest player payroll in the major leagues, with stalwarts like second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, third baseman Buck Weaver, and pitcher Cicotte being at or near the top of the pay scale for their positions.

Since it was first deployed as a trial stratagem by Black Sox defense lawyers in June 1921, motivation for the Series fix has been ascribed to the miserliness of Chicago club owner Charles A. Comiskey. The assertion is specious. Comiskey paid his charges the going rate and then some. In fact, salary data recently made available establish that the 1919 Chicago White Sox had the second highest player payroll in the major leagues, with stalwarts like second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, third baseman Buck Weaver, and pitcher Cicotte being at or near the top of the pay scale for their positions.

But the White Sox clubhouse was an unhealthy place, with the team long riven by faction. One clique was headed by team captain Eddie Collins, Ivy League-educated and self-assured to the point of arrogance. Aligned with Cocky Collins were Schalk, spitballer Red Faber, and outfielders Shano Collins and Nemo Leibold. The other, a more hardscrabble group united in envy, if not outright hatred, of the socially superior Collins, was headed by tough guy Gandil and the more amiable Cicotte. Also in their corner were Weaver, shortstop/fix enforcer Swede Risberg, outfielder Happy Felsch, and utilityman Fred McMullin.

According to the grand-jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte, his faction first began to discuss the feasibility of throwing the upcoming World Series during a train trip late in the regular season. Even before the White Sox clinched the 1919 pennant, Cicotte started to feel out Bill Burns, a former American League pitcher turned gambler, about financing a Series fix. Again according to Cicotte, the Sox were envious of the $10,000 payoffs rumored to have been paid certain members of the Chicago Cubs for dumping the 1918 Series against the Boston Red Sox. The lure of a similar score was enhanced by the low prospect of discovery or punishment.

Although they surfaced periodically, reports of player malfeasance were not taken seriously, routinely dismissed by the game’s establishment and denigrated in the sporting press. And the imposition of sanctions arising from gambling-related activity seemed to have been all but abandoned. Even charges of player corruption lodged by as revered a figure as Christy Mathewson and corroborated by affidavit were deemed insufficient grounds for disciplinary action, as attested by the National League’s recent exoneration of long-suspected game-fixer Hal Chase. By the fall of 1919, therefore, the fix of the World Series could reasonably be viewed from a player standpoint as a low risk/high reward proposition.

In mid-September the Gandil-Cicotte crew committed to the Series fix during a meeting at the Ansonia Hotel in New York. Likelihood of the scheme’s success was bolstered by the recruitment of the White Sox’ No. 2 starter, Lefty Williams, and the club’s batting star, outfielder Joe Jackson. In follow-up conversation with Burns, the parties agreed that the World Series would be lost to the National League champion Cincinnati Reds in exchange for a $100,000 payoff.

Financing a payoff of that magnitude was beyond Burns’s means, and efforts to secure backing from gambling elements in Philadelphia came up empty. Thereafter, Burns and sidekick Billy Maharg approached a potential fix underwriter of vast resource, New York City underworld financier Arnold Rothstein, known as the “Big Bankroll.” In all probability, word of the Series plot had reached Rothstein well before Burns and Maharg made their play. According to all concerned (Burns, Maharg, and Rothstein), Rothstein flatly turned down the proposal that he finance the Series fix. And from there, the plot to corrupt the 1919 World Series thickened.

The prospect of fix financing was revived by Hal Chase who, by means unknown, had also gotten wind of the scheme. Chase put Burns in touch with one of sportdom’s shadiest characters, former world featherweight boxing champ Abe Attell. A part-time Rothstein bodyguard and a full-time hustler, the Little Champ was constantly on the lookout for a score. Accompanied by an associate named “Bennett” (later identified as Des Moines gambler David Zelcer), Attell met with Burns and informed him that Rothstein had reconsidered the fix proposition and was now willing to finance it. The credulous Burns thereupon hastened to Cincinnati to rendezvous with the players on the eve of Game One.

In the meantime, the campaign to fix the Series had opened a second front. Shortly before the White Sox were scheduled to leave for Cincinnati, Gandil, Cicotte, Weaver, and other fix enlistees met privately at the Warner Hotel in Chicago. A mistrustful Cicotte demanded that his $10,000 fix share be paid in full before the team departed for Cincinnati. He then left the gathering to socialize elsewhere. The others remained to hear two men identified as “Sullivan” and “Brown” from New York. A confused Lefty Williams later testified that he was unsure if these men were the gamblers financing the fix or their representatives.

The first Warner Hotel fixer has always been identified as Gandil’s Boston pal, Sport Sullivan, but the true identity of “Brown” would remain a mystery to fix investigators. Decades later, first Rothstein biographer Leo Katcher and thereafter Abe Attell asserted that “Brown” was actually Nat Evans, a capable Rothstein subordinate and Rothstein’s junior partner in several gambling casino ventures. Whoever “Brown” was, $10,000 in cash had been placed under the bed pillow in Cicotte’s hotel room before the evening was over. The Series fix was now on, in earnest.

The Warner Hotel conclave was unknown to Burns, then trying to finalize his own fix arrangement with the players. He, Attell, and Bennett/Zelcer met with all the corrupted players, save Joe Jackson, at the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati sometime prior to the Series opener. After considerable wrangling, it was agreed that the players would be paid off in $20,000 installments following each White Sox loss in the best-five-of-nine Series.

Later that evening, Burns encountered an old acquaintance, Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton. Like most experts, Fullerton had confidently predicted a White Sox triumph. But something in the tone of Burns’s assurance that the Reds were a “sure thing” unsettled Fullerton. Burns made it sound as though the Series had already been decided. Almost simultaneously, betting odds on the Series shifted dramatically, with a last-minute surge of money transforming the once-underdog Reds into a slight Series favorite. To Fullerton and other baseball insiders, something ominous seemed to be afoot.

*****

To those unaware of these developments, the Game One matchup typified the inequity between the two sides. On the mound for the White Sox was 29-game-winner Eddie Cicotte, a veteran member of Chicago’s 1917 World Series champions and one of the game’s finest pitchers. Starting for Cincinnati was left-hander Dutch Ruether, who, prior to his 1919 season’s 19-win breakout, had won exactly three major-league games.

Aside from control master Cicotte plunking Reds leadoff batter Morrie Rath with his second pitch, the match proceeded unremarkably in the early going. Then Cicotte suddenly fell apart in the fourth. By the time stunned Chicago manager Kid Gleason had taken him out, the White Sox were behind 6-1. The final score was a lopsided Cincinnati 9, Chicago 1. Following their delivery of the promised loss, the players were stiffed, fix paymaster Attell reneging on the $20,000 payment due.

The White Sox fulfilled their side of the fix agreement in Game Two, in which Lefty Williams’s sudden bout of wildness in the fourth inning spelled the difference in a 4-2 Cincinnati victory. With the corrupted players now owed $40,000, Burns was hard-pressed to get even a fraction of that from Attell. Accusations of a double-cross greeted Burns’s delivery of only $10,000 to the players after the Game Two defeat. Still, he and Maharg accepted Gandil’s assurance that the Sox would lose Game Three. The two fix middlemen were then wiped out, losing their entire wagering stake when the White Sox posted a 3-0 victory behind the pitching of Dickey Kerr.

Whether the Series fix continued after Game Two is a matter of dispute. Joe Jackson would later inform the press that the Black Sox had tried to throw Game Three, only to be thwarted by Kerr’s superb pitching performance. Those maintaining that the White Sox were now playing to win often cite the decisive two-RBI single of erstwhile fix ringleader Chick Gandil.

With the Series now standing two games to one in Cincinnati’s favor, Cicotte retook the mound for Game Four, the most controversial of the Series. Locked in a pitching duel with Reds fireballer Jimmy Ring, Cicotte exhibited the pitching artistry that had been expected from him at the outset. His fielding, however, was another matter, with the game turning on two egregious defensive misplays by Cicotte in the Cincinnati fifth. Those miscues provided the margin in a 2-0 Cincinnati victory.

Cicotte later maintained that he had tried his utmost to win Game Four, but whether true or not, Eddie had received little offensive help from his teammates. The White Sox, both Clean and Black variety, were mired in a horrendous batting slump that would see the American League’s most potent lineup go an astonishing 26 consecutive innings without scoring. Chicago bats were silent again in Game Five, managing but three hits in a 5-0 setback that pushed the Sox to the brink of Series elimination.

Meanwhile, uncertainty reigned in gambling quarters. After the unscripted White Sox victory in Game Three, Burns, reportedly acting at the behest of Abe Attell, approached Gandil about resuming the fix. Gandil spurned him. But whether that brought the curtain down on the debasement of the 1919 World Series is far from clear. The Burns/Attell/Zelcer combine was not the only gambler group that the White Sox had taken money from. Admissions later made by the corrupted players make it clear that far more than the $10,000 post-Game Two payoff was disbursed during the Series. But who made these payoffs; when/where/how they were made; how much fix money in total was paid out by gambler interests, and how much of that money Gandil kept for himself, remain matters of conjecture.

More well-settled is the fact that awareness of the corruption of the World Series was fairly widespread in professional gambling circles. After the post-Game Two player/gambler falling-out, a group of Midwestern gamblers convened in a Chicago hotel to discuss a fix revival. Spearheading this effort were St. Louis clothing manufacturer/gambler Carl Zork and an Omaha bookmaker improbably named Benjamin Franklin, both of whom were heavily invested in a Reds Series triumph. The action, if any, taken by these Midwesterners is another uncertain element in the fix saga.

Back on the diamond, the White Sox teetered on the brink of elimination, having won only one of the first five World Series games. Their outlook turned bleaker in Game Six when the Reds rushed to an early 4-0 lead behind Dutch Ruether. At that late moment, slumbering White Sox bats finally awoke. Capitalizing on timely base hits from the previously dormant middle of the batting order (Buck Weaver, Joe Jackson, and Happy Felsch), the White Sox rallied for a 5-4 triumph in 10 innings. The ensuing Game Seven was the type of affair that sporting pundits had anticipated at the Series outset: a comfortable 4-1 Chicago victory behind masterly pitching by Eddie Cicotte and RBI-base hits by Jackson and Felsch.

Now only one win away from evening up the Series, the hopes of the White Sox faithful were pinned on regular-season stalwart Lefty Williams. Williams had pitched decently in his two previous Series outings, only to see his starts come undone by a lone big inning in each game. In Game Eight, disaster struck early. Lefty did not make it out of the first inning, leaving the White Sox an insurmountable 4-0 deficit. The Reds continued to pour it on against second-line Chicago relievers. Only a forlorn White Sox rally late in the contest made the final score somewhat respectable: Cincinnati 10, Chicago 5.

*****

The next morning, the sporting world’s approbation of the Reds’ World Series triumph was widespread, tempered only by a discordant note sounded by Hugh Fullerton. In a widely circulated column, Fullerton questioned the integrity of the White Sox’ Series performance. He also made the startling assertion that at least seven White Sox players would not be wearing a Chicago uniform the next season. More explicit but little-noticed charges of player corruption quickly followed in Collyer’s Eye, a horse-racing trade paper.

Although a few other intrepid baseball writers would later voice their own reservations about the Series bona fides, Fullerton’s commentary was not well-received by most in the profession. A number of fellow sportswriters characterized the Fullerton assertions as no more than the sour grapes of an “expert” embarrassed by the misfire of his World Series prediction. In a prominent New York Times article, special World Series correspondent Christy Mathewson also dismissed the Fullerton suspicions, informing readers that a fix of the Series was virtually impossible.

For its part, Organized Baseball mostly ignored Fullerton’s charges, leaving denigration of Fullerton and his allies to friendly organs like Baseball Magazine and The Sporting News. In the short run, the strategy worked. Despite reiteration in follow-up columns, Fullerton’s concerns gained little traction with baseball fans. By the start of the new season, the notion that the 1919 World Series had not been on the level was mostly forgotten — except at White Sox headquarters.

Unbeknownst to the sporting press or public, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey had not dismissed the allegations made against his team. While the 1919 Series was in progress, Comiskey had been disturbed by privately received reports that his team was going to throw the championship series. Shortly after the Series was over, club officials were dispatched to St. Louis to make discreet inquiry into fix rumors. Much to Comiskey’s chagrin, disgruntled local gambling informants endorsed the charge that members of his team had thrown the Series in exchange for a promised $100,000 payoff. Lingering doubt on that score was subsequently erased when in-the-know gamblers Harry Redmon and Joe Pesch repeated the fix details to Comiskey and other club brass during a late December meeting in Chicago.

Of the courses available to him, Comiskey opted to pursue the one of self-interest. Rather than expose the perfidy of his players and precipitate the breakup of a championship team, Comiskey kept his fix information quiet. Early in the new year, the corrupted players were re-signed for the 1920 season, with Joe Jackson, Happy Felsch, Swede Risberg, and Lefty Williams receiving substantial pay raises, to boot. Only fix ringleader Chick Gandil experienced any degree of Comiskey wrath; Gandil was tendered a contract for no more than his previous season’s salary. When, as expected, Gandil rejected the pact, Comiskey took pleasure in placing him on the club’s ineligible list. That suspension continued in force all season and effectively ended Chick Gandil’s playing career. He never appeared in a major-league game after the 1919 World Series.

From a financial standpoint, Comiskey’s silence paid off. Fueled by a return to pre-World War I “normalcy” and the unprecedented slugging exploits of a pitcher-turned-outfielder named Babe Ruth, major-league baseball underwent an explosion in popularity. With its defending AL champion team intact except for Gandil, the White Sox spent the 1920 season in the midst of an exciting three-way pennant battle with New York and Cleveland. With attendance at Comiskey Park soaring to new heights, club coffers overflowed with revenue. Then late in the 1920 season, it all began to unravel. The immediate cause was an unlikely one: the suspected fix of a meaningless late August game between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies.

At first the matter seemed no more than a distraction, the latest of the minor annoyances that bedeviled the game that season. That spring, baseball had been mildly discomforted by exposure of the game-fixing proclivities of Hal Chase, revealed during the trial of a breach-of-contract lawsuit instituted by black-sheep teammate Lee Magee. Then in early August, West Coast baseball followers were shaken by allegations that cast serious doubt upon the legitimacy of the 1919 Pacific Coast League crown won by the Vernon Tigers. In time, the PCL scandal would have momentous consequences, providing Commissioner Landis with instructive precedent for dealing with courtroom-acquitted Black Sox defendants. In the near term, however, the significance of these matters resided mainly in their effect upon Cubs president William L. Veeck Sr. Unhappy connection to both the Magee affair and the PCL scandal — Veeck’s boss, Cubs owner William Wrigley, was livid over the prospect that his Los Angeles Angels might have been cheated out of the PCL pennant — prompted Veeck to make public disclosure of the Cubs-Phillies fix reports and to pledge club cooperation with any investigative body wishing to delve into the matter.

Revelation that the outcome of the Cubs-Phillies game might have been rigged engaged the attention of two of the Black Sox Scandal’s most formidable actors: Cook County Judge Charles A. McDonald and American League President Ban Johnson. Only recently installed as chief justice of Chicago’s criminal courts and an avid baseball fan, McDonald promptly empaneled a grand jury to investigate the game fix reports.

But within days, influential sportswriter Joe Vila of the New York Sun, prominent Chicago businessman-baseball fan Fred Loomis, and others were pressing a more substantial target upon the grand jury: the 1919 World Series. Privately, Johnson, a longtime acquaintance of Judge McDonald, urged a similar course upon the jurist. Like Comiskey, Johnson had conducted his own confidential investigation into the outcome of the 1919 Series. And he too had uncovered evidence that the Series had been corrupted. McDonald was amenable to expansion of the grand jury’s probe, and by the time the grand jury conducted its first substantive session on September 22, 1920, inquiry into the Cubs-Phillies game had been relegated to secondary status. The panel’s attention would be focused on the 1919 World Series.

The ensuing proceedings were remarkable for many reasons, not the least of which was the wholesale disregard of the mandate of grand-jury secrecy. Violation of this black-letter precept of law was justified on the dubious premise that baseball would benefit from the airing of its dirty laundry, and soon newspapers nationwide were reporting the details, often verbatim, of grand-jury testimony.

This breach of law was accompanied by another extra-legal phenomenon: almost daily public commentary on the proceedings by the grand-jury foreman, the prosecuting attorney, and, on occasion, Judge McDonald himself. In a matter of days, the transparency of the proceedings permitted the Chicago Tribune to announce the impending indictment of eight White Sox players: Eddie Cicotte, Chick Gandil, Joe Jackson, Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, Happy Felsch, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin — the men soon branded the Black Sox. For the time being, the charge against them was the generic conspiracy to commit an illegal act. The scandal spotlight then shifted briefly to Philadelphia, where a fix insider was giving the interview that would blow the scandal wide open.

In the September 27, 1920, edition of the Philadelphia North American, Billy Maharg declared that Games One, Two, and Eight of the 1919 World Series had been rigged. According to Maharg, the outcome of the first two games had been procured by the bribery of the White Sox players by the Burns/Attell/Bennett combine. The abysmal pitching performance that cost Chicago any chance of winning Game Eight was the product of intimidation of Lefty Williams by the Zork-Franklin forces, Maharg implied.

Wire service republication of the Maharg expose produced swift and stunning reaction. A day later, first Eddie Cicotte and then Joe Jackson admitted agreeing to accept a payoff to lose the Series when interviewed in the office of White Sox legal counsel Alfred Austrian. The two then repeated this admission under oath before the grand jury. Interestingly, neither Cicotte nor Jackson confessed to making a deliberate misplay during the Series. Press accounts that had Cicotte describing how he lobbed hittable pitches to the plate and/or had Jackson admitting to deliberate failure in the field or at bat were entirely bogus. According to the transcriptions of their testimony, the two had told the grand jury no such thing. While each had taken the gamblers’ money, Cicotte and Jackson both insisted that they had played to win at all times against the Reds. The other player participants in the Series fix were identified by Cicotte and Jackson, but apart from laying blame on Gandil, neither man disclosed much knowledge of how the fix had been instigated or who had financed it.

This exercise repeated itself when Lefty Williams spoke the following day. Like Cicotte and Jackson, Lefty admitted joining the fix conspiracy and accepting gamblers’ money, first confessing in the Austrian law office, and thereafter in testimony before the grand jury. But Williams also denied that he had done anything corrupt on the field to earn his payment. He said he had tried his best at all times, even during his dismal Game Eight start. For the grand-jury record, Lefty officially identified the fix participants as “Cicotte, Gandil, Weaver, Felsch, Risberg, McMullin, Jackson, and myself.” Williams also put names on some of the gambler co-conspirators. At the Warner Hotel in Chicago, they had been named “Sullivan” and “Brown.” At the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati, the fix proponents had been Bill Burns, Abe Attell, and a third man named “Bennett.”

A similar tack was taken by Happy Felsch when interviewed by a reporter for the Chicago Evening American. Like the others, Felsch admitted his complicity in the fix plot and his acceptance of gamblers’ money. But his subpar Series performance, particularly in center field, had not been deliberate, he said. Lest the underworld get the wrong idea, Felsch hastened to add that he had been prepared to make a game-decisive misplay, but the opportunity to do so had not presented itself during the Series. Unlike the others, Happy confined admission of wrongdoing to himself, although he had come to admire the way that Cicotte had demanded his payoff money up-front. Felsch did not know who had financed the fix, but he was willing to subscribe to press reports that it had been Abe Attell.

A far different public stance was adopted by the other Black Sox. Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, Fred McMullin, and Buck Weaver all protested their innocence, with Weaver in particular adamant about his intention to obtain legal counsel and fight any charges preferred against him in court. Those charges would not be long in coming. On October 29, 1920, five counts of conspiracy to obtain money by false pretenses and/or via a confidence game were returned against the Black Sox by the grand jury. Gamblers Bill Burns, Hal Chase, Abe Attell, Sport Sullivan, and Rachael Brown were also charged in the indictments.

*****

The stage thereupon shifted to the criminal courts for a whirl of legal events, few of which are accurately described or well understood in latter-day Black Sox literature.

The return of criminal charges in the Black Sox case coincided with the Republican Party’s political landslide in the November 1920 elections. An entirely different administration soon took charge of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, the prosecuting agency in the baseball scandal. When the regime of new State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe assumed office, it found the high-profile Black Sox case in disarray. The investigation underlying the indictments was incomplete. Evidence was missing from the prosecutors’ vault, including transcriptions of the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand-jury testimony.

Worse yet, it appeared that their predecessors in office had premised prosecution of the Black Sox case on cooperation anticipated from Cicotte, Jackson, and/or Williams, each of whom had admitted fix complicity before the grand jury. But now, the trio was standing firm with the other accused players, and seeking to have their grand-jury confessions suppressed by the court on legal grounds. This placed the new prosecuting attorneys in desperate need of time to rethink and then rebuild their case.

In March 1921, prosecutors’ hopes for an adjournment were dashed by Judge William E. Dever, who set a quick peremptory trial date. This prompted a drastic response from prosecutor Crowe. Rather than try to pull the Black Sox case together on short notice, he administratively dismissed the charges. Crowe coupled public announcement of this stunning development with the promise that the Black Sox case would be presented to the grand jury again for new indictments.

Before the month was out, that promise was fulfilled. Expedited grand-jury proceedings yielded new indictments that essentially replicated the dismissed ones. All those previously charged were re-indicted, while the roster of gambler defendants was enlarged to include Carl Zork, Benjamin Franklin, David (Bennett) Zelcer, and brothers Ben and Lou Levi, reputedly related to Zelcer by marriage and long targeted for prosecution by AL President Ban Johnson.

With the legal proceedings now reverting to courtroom stage one, prosecutors had acquired the time necessary to get their case in better shape. That extra time was needed, as the prosecution remained besieged on many fronts. The State was deluged by defense motions to dismiss the charges, suppress evidence, limit testimony, and the like. Prosecutors were also having trouble getting the gambler defendants into court. Sport Sullivan and Rachael Brown remained somewhere at large. Hal Chase and Abe Attell successfully resisted extradition to Chicago, and Ben Franklin was excused from the proceedings on grounds of illness.

Former major-league pitcher Bill Burns was the prosecution’s star witness in the Black Sox criminal trial in 1921. It took quite an adventure — and a lot of money from the American League treasury — to get him on the stand. (BaseballHall.org)

In the run-up to trial, however, prosecution prospects received one major boost. Retrieved from the Mexican border by his pal Billy Maharg (via a trip financed by Ban Johnson), Bill Burns had agreed to turn State’s evidence in return for immunity. Now, prosecutors had the crucial fix insider that their case had been lacking.

Jury selection began on June 16, 1921, and dragged on for several weeks. Appearing as counsel on behalf of the accused were some of the Midwest’s finest criminal defense lawyers: Thomas Nash and Michael Ahern (representing Weaver, Felsch, Risberg, and McMullin; McMullin did not arrive in Chicago until after jury selection had begun, and for this reason, the trial went on without him and the charges against him were later dismissed); Benedict Short and George Guenther (Jackson and Williams); James O’Brien and John Prystalski (Gandil); A. Morgan Frumberg and Henry Berger (Zork), and Max Luster and J.J. Cooke (Zelcer and the Levi brothers). Cicotte, meanwhile, was represented by his friend and personal attorney Daniel Cassidy, a civil lawyer from Detroit.

Although outnumbered, the prosecution was hardly outgunned, with its chairs filled by experienced trial lawyers: Assistant State’s Attorneys George Gorman and John Tyrrell, and Special Prosecutor Edward Prindiville, with assistance from former Judge George Barrett representing the interests of the American League in court, and a cadre of attorneys in the employ of AL President Johnson working behind the scenes.

About the only unproven commodity in the courtroom was the newly assigned trial judge, Hugo Friend. Judge Friend would later go on to a distinguished 46-year career on Illinois trial and appellate benches. But at the time of the Black Sox trial, he was a judicial novice, presiding over his first significant case. Although his mettle would often be tested by a battalion of fractious barristers, Friend’s intelligence and sense of fairness would stand him in good stead. The Black Sox case would be generally well tried, if not error-free.

In a sweltering midsummer courtroom, the prosecution commenced its case with the witnesses needed to establish factual minutiae — the scores of 1919 World Series games, the employment of the accused players by the Chicago White Sox, the winning and losing Series shares, etc. — that the defense, for tactical reasons, declined to stipulate. Then, chief prosecution witness Bill Burns assumed the stand. For the better part of three days, Burns recounted the events that had precipitated the corruption of the 1919 World Series. Those who had equated Burns with his “Sleepy Bill” nickname were in for a shock. Quick-witted and unflappable, Burns was more than a match for sneering defense lawyers, much to the astonishment, then delight, of the jaded Black Sox trial press corps. Newspaper reviews of Burns’s testimony glowed and, by the time their star witness stepped down, prosecutors were near-jubilant. Thereafter, prosecution focus temporarily shifted to incriminating Zork and the other Midwestern gambler defendants.

Halfway through the State’s case, the jury was excused while the court conducted an evidentiary hearing into the admissibility of the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand-jury testimony. Modern accounts of the Black Sox saga often relate that the prosecution was grievously injured by the loss of grand-jury documents. That was hardly the case. When prosecutors discovered that the original grand-jury transcripts were missing, they merely had the grand-jury stenographers create new ones from their shorthand notes. These second-generation transcripts were available throughout the proceedings, and Black Sox defense lawyers did not contest their accuracy.

What was contested was whether, and to what extent, the trial jury should be made privy to what Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams had told the grand jurors. According to the defense, the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand-jury testimony had been induced by broken off-the-record promises of immunity from prosecution. If this were true, the testimony would be deemed involuntary in the legal sense and inadmissible against the accused.

With testimony restricted exclusively to what had happened in and around the grand-jury room, the proceedings devolved into a swearing contest. Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams testified that they had been promised immunity. Lead grand-jury prosecutor Hartley Replogle and Judge McDonald denied it. During the hearing, grand-jury excerpts were read into the record at length. After hearing both sides, Judge Friend determined that the defendants had confessed freely, without any promise of leniency. Their grand-jury testimony would be admissible in evidence — but not before each grand-jury transcript had been edited to delete all reference to Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, or anyone else mentioned in it, other than the speaker himself. Once this tedious task was accomplished, the redacted grand-jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams was read to the jury, a prolonged and dry exercise that seemed to anesthetize most panel members.

The numbing effect that the transcript readings had on the jury was not lost on prosecutors. Wishing to close their case while it still enjoyed the momentum of the Burns testimony, prosecutors made a fateful strategic decision. They jettisoned the remainder of their scheduled witnesses (Ban Johnson, Joe Pesch, St. Louis Browns second baseman Joe Gedeon, et al.) and wrapped up the State’s case with another fix insider: unindicted co-conspirator Billy Maharg. The affable Maharg provided an account of the fix developments that he was witness to, providing firm and consistent corroboration of many fix details supplied by Bill Burns earlier.

Pleased with Maharg’s performance, prosecutors rested their case. Now they would be obliged to accept the cost of short-circuiting their proofs. In response to defense motions, Judge Friend dismissed the charges against the Levi brothers for lack of evidence. He also signaled that he would be disposed to overturn any guilty verdict returned by the jury against Carl Zork, Buck Weaver, or Happy Felsch, given the thinness of the incriminating evidence presented against them. These rulings, however, did not visibly trouble the prosecutors, for they had plainly decided to concentrate their efforts on convicting defendants Gandil, Cicotte, Jackson, Williams, and the gambler David Zelcer.

The defense had long advertised that the Black Sox would be testifying in their own defense. But that would have to wait, as the gambler defendants would be going first. Once the Zelcer and Zork defenses had presented their cases, the Gandil defense took the floor, calling a series of witnesses mainly intended to make a liar out of Bill Burns.

Also presented was White Sox club secretary Harry Grabiner, whose testimony about soaring 1920 club revenues undermined the contention that team owner Comiskey or the White Sox corporation had been injured by the fix of the 1919 World Series. (Years later, jury foreman William Barry would tell Judge Friend that the Grabiner testimony had had more influence on the jury than that of any other witness.)

Then, with the stage finally set for Chick to take the stand, the Gandil defense abruptly rested. So did the other Black Sox. Little explanation for this change in defense plan was offered, apart from the comment that there was no need for the accused players to testify because the State had made no case against them. Caught off-guard by defense maneuvers, the prosecution scrambled to present rebuttal witnesses, most of whom were excluded from the testifying by Judge Friend. As little in the way of a defense had been mounted by the player defendants, there was no legal justification for admitting rebuttal.

The remainder of the trial was devoted to closing stemwinders by opposing counsel and the court’s instructions on the law. Then the jury retired to deliberate. Less than three hours later, it reached a verdict. With the parties reassembled in a courtroom packed with defense partisans, the court clerk announced the outcome: Not Guilty, as to all defendants on all charges. A smiling Judge Friend concurred, pronouncing the jury’s verdict a fair one.

Minutes after the Black Sox were acquitted on August 2, 1921, the players, their attorneys, and members of the jury (in shirt sleeves) celebrated the verdict by posing for a photo on the courthouse steps. (Chicago Tribune)

With that, pandemonium erupted. Jurors shook hands and congratulated the men whom they had just acquitted. Some in the crowd even hoisted defendants onto their shoulders and paraded them around. Thereafter, defendants, defense lawyers, jurors, and defense followers gathered on the courthouse steps, where their mutual joy was captured in a photo published by the Chicago Tribune. Later, a post-verdict celebration brought the defendants and the jurors together once again at a nearby Italian restaurant. There, the revelry continued into the wee hours of the morning, closing with jurors and Black Sox singing “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here.”

This extraordinary exhibition of camaraderie suggests that the verdict may have been a product of that courthouse phenomenon that all prosecutors dread: jury nullification. In a criminal case, jurors are carefully instructed to abjure passion, prejudice, sympathy, and other emotion in rendering judgment. They are to base their verdict entirely on the evidence presented and the law. But during deliberations in highly charged cases, this instruction is susceptible to being overridden by the jury’s identification with the accused. Or by dislike of the victim. Or by the urge to send some sort of message to the community at large.

In the Black Sox case, defense counsel, notably Benedict Short and Henry Berger, worked assiduously to cultivate a bond between the working-class men on the jury and the blue-collar defendants. The defense’s closing arguments to the jury, particularly those of Short, Thomas Nash, A. Morgan Frumberg, and James O’Brien, stridently denounced the wealthy victim Comiskey and his corporation. The defense lawyers also raised the specter of another menace: AL President Ban Johnson, portrayed as a malevolent force working outside of jury view to ensure the unfair condemnation of the accused.

In the end, of course, the underlying basis for the jury’s acquittal of the Black Sox is unknowable all these years later. Significantly, the fair-minded Judge Friend concurred in the outcome. Still, jury nullification remains a plausible explanation for the verdict, particularly when it came to jurors’ resolution of the charges against defendants Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams, against whom the State had presented a facially strong case.

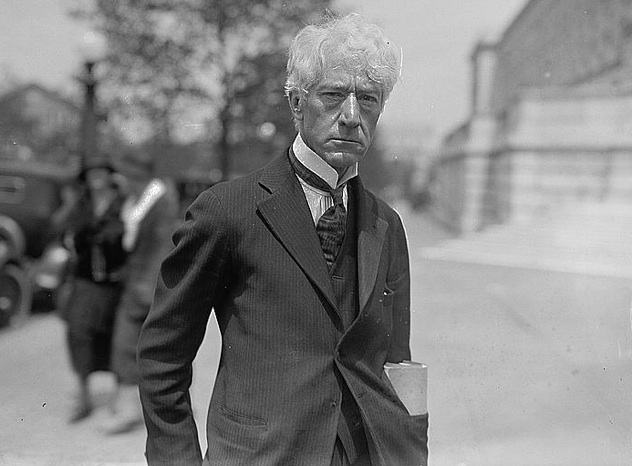

Few others shared the jurors’ satisfaction in their verdict, with many baseball officials vowing never to grant employment to the acquitted players. That sentiment was quickly rendered academic. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis had taken note of the minor leagues’ prompt expulsion of the Pacific Coast League players who had had their indictments dismissed by the judge in that game-fixing case. Landis, who had been hired as commissioner in November 1920, now utilized that action as precedent.

With a famous edict that began “Regardless of the verdict of juries …,” Landis permanently barred the eight Black Sox players from participation in Organized Baseball. And with that, Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Buck Weaver, and the rest were consigned to the sporting wilderness. None would ever appear in another major-league game. The Black Sox saga, however, was not quite over.

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned the eight Black Sox players for life from Organized Baseball in 1921. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

*****

In the aftermath of their official banishment from the game, Buck Weaver, Happy Felsch, Swede Risberg, and Joe Jackson instituted civil litigation against the White Sox, pursuing grievances grounded in breach of contract, defamation, and restraint on their professional livelihoods.

Outside of Milwaukee, where the Felsch/Risberg/Jackson suits were filed, little attention was paid to their complaints. Jackson’s breach-of-contract suit was the only one that ever went to trial. It was founded on the three-year contract that Jackson had signed with the White Sox in late February 1920, months after the World Series. The club had unilaterally voided the pact when it released Jackson in March 1921, and he had gone unpaid for the 1921 and 1922 baseball seasons.

In a pretrial deposition, plaintiff Jackson disputed that his termination by the White Sox had been justified by his involvement in the Series fix. On that point, Jackson swore to a set of fix-related events dramatically at odds with his earlier grand-jury testimony. Jackson now maintained that he had had no connection to the conspiracy to rig the 1919 Series. He had not even known about it until after the Series was over, when a drunken Lefty Williams foisted a $5,000 fix share on Jackson, telling him that the Black Sox had used Jackson’s name while trying to persuade gamblers to finance the fix scheme.

When the suit was tried in early 1924, its highlight was Jackson’s cross-examination by White Sox attorney George Hudnall. Confronted with his grand-jury testimony of September 28, 1920, Jackson did not attempt to explain away the contradiction between his civil deposition assertions and his grand-jury testimony. Nor did he attempt to harmonize the two. Rather, Jackson maintained — more than 100 times — that he had never made the statements contained in the transcript of his grand-jury testimony.

An outraged Judge John J. Gregory subsequently cited Jackson for perjury and had him jailed overnight. The court vacated the jury’s $16,711.04 award in Jackson favor, ruling that it was grounded in false testimony and jury nonfeasance. After the proceedings were over, civil jury foreman John E. Sanderson shed light on the jury’s thinking. Sanderson informed the press that the jury had entirely disregarded Jackson’s testimony about disputed events. The foreman also rejected the notion that the panel had exonerated Jackson of participation in the 1919 World Series fix.

Rather, the jury had premised its judgment for Jackson on the legal principle of condonation. As far as the jury was concerned, White Sox team brass had known of Jackson’s World Series fix involvement well before the new three-year contract was tendered to him in February 1920. Having thus effectively condoned (or forgiven) Jackson’s Series misconduct by re-signing him, the club was in no position to void that contract once the public found out what club management had known about Jackson all along. Jackson was, according to the Milwaukee jury, therefore entitled to his 1921 and 1922 pay.

In time, the four civil lawsuits, including that of Jackson, were settled out of court for modest sums. Little notice was taken, as the baseball press and public had long since moved on. In the ensuing years, the Black Sox Scandal receded in memory, recalled only in the random sports column, magazine article, or, starting with the death of Joe Jackson in December 1951, the obituary of a Black Sox player.

Revival of interest in the scandal commenced in the late 1950s, but did not attract widespread attention until the publication of Eliot Asinof’s classic Eight Men Out in 1963. Regrettably, this spellbinding account of the scandal was marred by historically inaccurate detail, attributable presumably to the fact that much of the criminal case record had been unavailable to Asinof, having disappeared from court archives over the years. This had compelled Asinof to rely upon scandal survivors, particularly Abe Attell, an engaging but unreliable informant.

Asinof also exercised artistic license in his work, creating, apparently for copyright protection purposes, a fictitious villain named “Harry F.” to intimidate Lefty Williams into his dreadful Game Eight pitching performance. Asinof likewise embellished his tale of the Jackson civil case, inserting melodramatic events, such as White Sox lawyer Hudnall pulling a supposedly lost Jackson grand-jury transcript out of his briefcase in midtrial, into Eight Men Out that are nowhere memorialized in the fully extant record of the civil proceedings.

Over the years, the embrace of such Asinof inventions, as well as the repetition of more ancient canards — the miserly wage that Comiskey supposedly paid the corrupted players, the notion that disappearing grand-jury testimony hamstrung the prosecution, and other fictions – has become a recurring feature of much Black Sox literature.

In 2002 scandal enthusiast Gene Carney commenced a near-obsessive re-examination of the Black Sox affair. First in weekly blog posts and later in his important book Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Potomac Books, 2006), Carney circulated his findings, which were often at variance with long-accepted scandal wisdom. Sadly, this work was cut short by Carney’s untimely passing in July 2009. But the mission endures, carried on by others, including the membership of the SABR committee inspired by Carney’s zeal.

That scandal revelations are still to be made is clear, manifested by events like the surfacing of a treasure trove of lost Black Sox documents acquired by the Chicago History Museum several years ago. As the playing of the 1919 World Series approaches its 100th anniversary, the investigation continues. And the final word on the Black Sox Scandal remains to be written.

WILLIAM F. LAMB is the author of “Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation” (McFarland & Co., 2013). He spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey. In retirement, he lives in Meredith, New Hampshire, and serves as the editor of “The Inside Game,” the quarterly newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Research Committee. He has contributed more than 50 bios to the SABR BioProject.

Sources

This essay is drawn from a more comprehensive account of the Black Sox legal proceedings provided in the writer’s Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial, and Civil Litigation (McFarland & Co., 2013). Underlying sources include surviving fragments of the judicial record; the Black Sox Scandal collections maintained at the Chicago History Museum and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Giamatti Research Center; the transcript of Joe Jackson’s 1924 lawsuit against the Chicago White Sox held by the Chicago Baseball Museum; newspaper archives in Chicago and elsewhere; and contemporary Black Sox scholarship, particularly the work of Gene Carney, Bob Hoie, and Bruce Allardice.