July 26, 1942: Monarchs’ Satchel Paige garners the victory on day in his honor at Wrigley Field

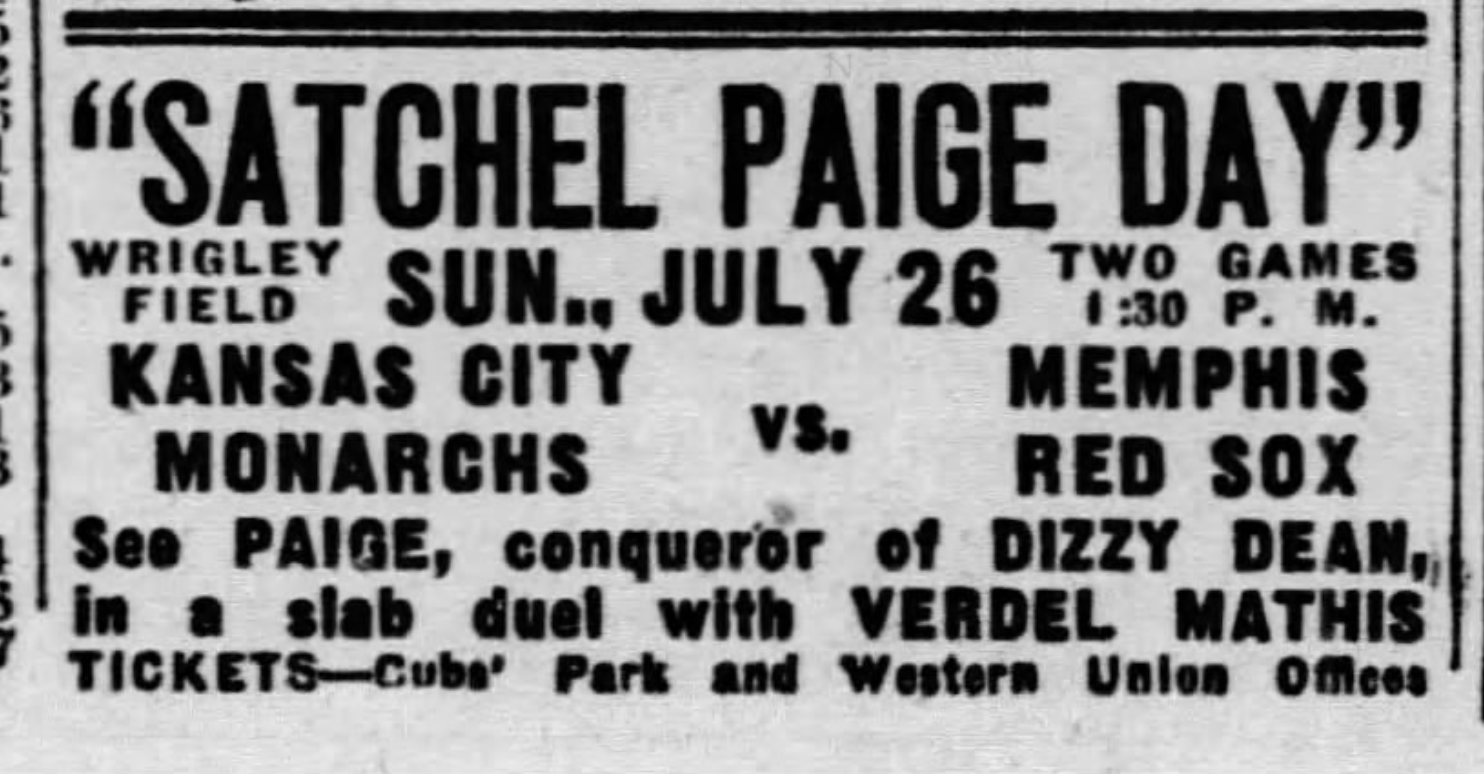

Negro League historian James A. Riley wrote about Satchel Paige, “A mixture of fact and embellishment, Satchel’s stories are legion and form a rich array of often-repeated folklore.”1 There is truth in the assertion that a lot of myth-making has been involved in constructing Paige’s life story: however, as Riley also noted, “The stories are endless. But the facts are also impressive.”2 Such was the case on the occasion of Satchel Paige Day at Chicago’s Wrigley Field on Sunday, July 26, 1942. Kansas City Monarchs co-owner J.L. Wilkinson, ace promoter Abe Saperstein of Harlem Globetrotters fame, and the Chicago Defender set a propaganda machine in motion to promote the first-ever day to be held in Paige’s honor.3

Negro League historian James A. Riley wrote about Satchel Paige, “A mixture of fact and embellishment, Satchel’s stories are legion and form a rich array of often-repeated folklore.”1 There is truth in the assertion that a lot of myth-making has been involved in constructing Paige’s life story: however, as Riley also noted, “The stories are endless. But the facts are also impressive.”2 Such was the case on the occasion of Satchel Paige Day at Chicago’s Wrigley Field on Sunday, July 26, 1942. Kansas City Monarchs co-owner J.L. Wilkinson, ace promoter Abe Saperstein of Harlem Globetrotters fame, and the Chicago Defender set a propaganda machine in motion to promote the first-ever day to be held in Paige’s honor.3

By 1942 Paige was already a living legend among Negro League players and fans. The Defender noted that Paige had long “been coming to Chicago thrilling the fans with his hurling feats. He has pitched in charity games benefitting hospitals, boys’ clubs and other fine causes.”4 Thus, as the newspaper asserted, “his admirers … feel it is about time that he be the recipient of a day in his honor.”5 Wilkinson and Saperstein considered Wrigley Field to be the ideal venue, and they scheduled the Memphis Red Sox, the Monarchs’ Negro American League rivals, as the opponent for the day’s doubleheader. In addition to the accolades and gifts to be showered upon Paige between games, the nightcap was to be a “revenge game” between Paige and Memphis hurler Verdell “Lefty” Mathis.6

Mathis was having a breakout season and had prevailed against Paige twice already in the 1942 season. On May 17 he had triumphed, 4-1, in the second game of a doubleheader on Opening Day at Kansas City’s Ruppert Stadium. Mathis had held the Monarchs to two hits in the seven-inning game, while the Defender had described the contest as “a nightmare for Satchel Paige,” who surrendered 10 hits and six walks.7 Then, on July 7, at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, Mathis again won, 1-0, in 10 innings.8 There was a caveat to this second game, however, in that Paige pitched only the first five innings for Kansas City, allowing three hits. Connie Johnson pitched the final five frames for the Monarchs and was the losing pitcher. Nevertheless, most newspaper articles invariably stated that Mathis had defeated Paige twice. Thus, the idea of a grudge rematch had been conceived.

As it turned out, Paige and Mathis opposed each other again just five days later at Rebel Stadium in Dallas, Texas. In the first game of a July 12 doubleheader which – for reasons unknown – was also shortened to seven innings, Paige showed his mettle. He went the distance in an 11-0 shutout, and “proved he could do more than just pitch by banging out a double and two singles in four times at bat.”9

Paige’s dominance in Dallas almost scuttled Wilkinson and Saperstein’s “revenge” hype machine, but the Defender conveniently ignored that game as it helped to promote the Wrigley Field matchup for all it was worth. In its July 25 edition, the Defender ran a preview article for the next day’s doubleheader that contained quotes from both pitchers. Mathis had idolized Paige as a young boy, so it is unlikely that he truly held any rancor toward the Monarchs hurler, but he dutifully played along by stating, “I beat him before and I’ll beat him again … and I’ll beat him Sunday.”10 Paige, who was never shy about boasting, replied, “Bring on Mathis. … I’ve beaten better pitchers than he is and I’ll be ready for him Sunday.”11

When the big day finally arrived, 20,000 fans were in attendance at Wrigley Field. It is a certainty that none of them were there out of great interest in the first game, in which Memphis pitcher Porter “Ankleball” Moss earned the win as the Red Sox clipped the Monarchs and future Hall of Famer Hilton Smith, 10-4.12 One event that had attracted so many spectators took place between games as Paige was feted by the Defender. Standing at home plate, Paige received a huge ovation and was presented with a basket of flowers and an Elgin gold watch from the newspaper in addition to a radio, clothing, and other items that were given by various businesses and organizations. Mathis, the other half of the day’s feature attraction, received a traveling bag from his team.13

Paige received his second ovation of the day when he took the mound in the top of the first inning of the nightcap, which was the game most fans had come to see.14 The cliché that “it’s not bragging if you can back it up” can undoubtedly be applied to Paige, and his fourth matchup against Mathis provided another instance in which he demonstrated his knack for rising to the top on a major occasion.

Paige set the Red Sox batters down in order in the first two innings. Memphis had traffic on the basepaths in the third inning but to no avail. Paige walked leadoff batter Tom “T.J.” Brown, but catcher Frank Duncan gunned him down as he attempted to steal second. After that, Memphis catcher Larry Brown reached first safely on Newt Allen’s error at third base, but Paige picked him off first and then struck out Mathis to retire the side.

Mathis kept pace with Paige for the first two innings, though he was aided greatly by third baseman Marlin Carter’s unassisted double play that got him out of a second-inning jam in which he had runners on second and third with only one out. Paige’s determination to win on his day came to the fore when he singled to lead off the bottom of the third. He advanced to second on Willie Simms’s sacrifice, made it to third on a single by Allen, and crossed home plate on Ted Strong’s fly to center. Mathis induced a grounder from Willard Brown to end the inning, but he now trailed Paige and the Monarchs.

While Paige continued to cruise, the Monarchs added to their lead in the next two innings. In the bottom of the fourth, Jesse Williams hit a one-out single, advanced to third on Bonnie Serrell’s base hit to right field, and scored on a sacrifice fly by Duncan. Then, in the sixth, Mathis walked the first two batters, Allen and Strong, and surrendered consecutive singles to Brown and Buck O’Neil that resulted in a 4-0 deficit.

For six innings, Paige had allowed the Red Sox only three hits and had kept them off the scoreboard. However, Memphis mounted a late challenge that caused the Atlanta Daily World to lament that Paige “would probably have had a shutout had there not been an error behind him in the seventh.”15 Carter singled to lead off the inning, and the next batter, Olan “Jelly” Taylor, was safe when Allen airmailed his throw from third base on Taylor’s grounder. Allen’s throw was so wild that Carter scored and Taylor got to third. Subby Byas pinch-hit for Tom Brown and grounded out to O’Neil at first, but Taylor scored as O’Neil opted not to try for a play at home plate. After that last bit of excitement, Paige got the final out to preserve a 4-2 triumph.

Although Memphis had been able to throw a minor scare into the Monarchs at the end of the game, it had seemed a foregone conclusion that there was no way Paige was going to lose a game on a day held in his honor. Whether it involved winning a championship for a foreign dictator, calling in the outfield while he struck out the side, or walking the bases loaded so that he could face Josh Gibson – the most-feared batter in the Negro Leagues – and then strike him out, the lanky Paige always came out on top when the spotlight shined brightest on him.

Sources

The play-by-play account of the game was adapted from the following article:

“Chicago Fans Honor Satchel Paige Who Wins 4-2,” Chicago Defender, August 1, 1942: 19.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 598.

2 Riley, 598.

3 Mark Ribowsky, Don’t Look Back: Satchel Paige in the Shadows of Baseball (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 209.

4 “Chicago to Honor Satchel Paige Sunday/Paige Will Face Lefty Mathis and Memphis at Wrigley Field July 26,” Chicago Defender, July 25, 1942: 19.

5 “Chicago to Honor Satchel Paige Sunday.”

6 “Paige Faces Mathis in Revenge Game at Cub’s [sic] Park, Sunday, July 26,” Chicago Defender, July 18, 1942: 20.

7 “Kansas City Splits Even with Memphis,” Chicago Defender, May 23, 1942: 20.

8 “Memphis Red Sox Defeat Monarchs in Tenth Inning,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 8, 1942: 14.

9 “Opponents Blanked by Negro Pitcher,” Dallas Morning News, July 13, 1942: 7. Although this game took place two weeks before the Paige-Mathis duel at Wrigley Field, it was reported only in the local press; not only the Defender, but all other newspapers failed to mention the game in preview articles about the Satchel Paige Day matchup between the two hurlers. However, Mathis still recalled it decades later, saying, “I remember in Dallas one Sunday it was awful hot. Satchel beat me down there.” See John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (New York: Stadium Books, 1991), 148.

10 “Chicago to Honor Satchel Paige Sunday.”

11 “Chicago to Honor Satchel Paige Sunday.”

12 The Chicago Defender gave the attendance as 18,000 in its August 1 article about Satchel Paige Day, but all other newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune (July 27), Chicago Times (July 27), and Atlanta Daily World (August 1), reported the attendance as 20,000.

13 “Chicago Fans Honor Satchel Paige Who Wins 4-2,” Chicago Defender, August 1, 1942: 19; “Kansas City and Memphis Divide Paige Day Games,” Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1942: 17.

14 The game was scheduled to go seven innings, as was the case with the second games of all Negro League doubleheaders.

15 “Satchel Paige Thrills Crowd in Chicago Tilt,” Atlanta Daily World, August 1, 1942: 5.

Additional Stats

Kansas City Monarchs 4

Memphis Red Sox 2

7 innings

Game 2, DH

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.