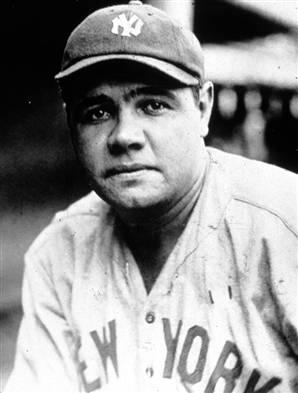

June 1, 1925: Babe Ruth returns from ‘Bellyache Heard ‘Round the World’

Babe Ruth got a huge cheer when he stepped onto the field at Yankee Stadium on June 1, 1925 — a well-deserved ovation considering that just a few months ago he was dead. The announcement of his demise was wildly inaccurate, of course, but it was right there in black and white in newspapers around the world. One Scottish paper ran the headline BASEBALL FANS GET SHOCK: IDOL OF THE CROWDS REPORTED DEAD.1 Similar reports appeared in papers in London, Belfast, and elsewhere. The New York Times noted the next day that the false story had begun in Canada for unknown reasons and “spread with almost incredible rapidity.”2

Babe Ruth got a huge cheer when he stepped onto the field at Yankee Stadium on June 1, 1925 — a well-deserved ovation considering that just a few months ago he was dead. The announcement of his demise was wildly inaccurate, of course, but it was right there in black and white in newspapers around the world. One Scottish paper ran the headline BASEBALL FANS GET SHOCK: IDOL OF THE CROWDS REPORTED DEAD.1 Similar reports appeared in papers in London, Belfast, and elsewhere. The New York Times noted the next day that the false story had begun in Canada for unknown reasons and “spread with almost incredible rapidity.”2

While the report of his demise was an exaggeration to say the least (and no doubt a surprise to Ruth), the diagnosis of Dr. Edward King was quite serious. Babe had persistent high fevers all during spring training and collapsed in a train station in Asheville, North Carolina, after a preseason game.3 He had to be hospitalized and operated on. Some reports said it was influenza but this wasn’t a consensus opinion. There were whispers that he’d never play again and that “the true nature of his illness was being kept secret.”4 Sportswriter W.O. McGeehan penned the lasting story that Ruth’s ailment was the result of eating a dozen hot dogs and a legend was born. The incident became known as “the bellyache heard round the world.”5

The hot-dog story was pure fiction, an example of the colorful writing of the time, made believable by the true gluttonous personality of The Babe. There were alternate theories, including the suggestion that it wasn’t his stomach but something lower.6 The rumor persists that the team was spinning a kid-friendly hot-dog theory to cover up a sexually transmitted disease. However believable this also sounds (see: Babe’s gluttonous personality), it’s not true.

Ruth went under the knife to treat an abscess; he had a scar and it took weeks to recover — not treatment consistent with venereal disease.7 If there was an attempt to hide the truth, it was probably because Babe’s prodigious alcohol consumption was at least partially to blame — an awkward fact during the era of prohibition. Babe was a heavy imbiber, there was a lack of quality control in moonshine, and alcohol poisoning was common. Although never confirmed as the cause of Ruth’s abscess and intestinal issues, all that homemade booze certainly did not help.

The newspapers and fans anxiously followed Ruth’s stay in New York’s St. Vincent Hospital; he was at the height of his fame in 1925. He was the game’s — and probably the country’s — biggest star. Original estimates from the Yankees predicted he’d be back in uniform in May. As the month went on, it was clear he wasn’t ready. Revised estimates predicted the middle of June. A May 27 report said he was discharged from the hospital, but that he remained “a delicate if interesting invalid.”8 He appeared far from a return.

But Ruth must have grown restless, a condition not improved by watching the Yankees — who came in second the year before and expected to compete for the pennant — plummet in the standings. It was suddenly announced that he would be in the lineup on June 1 to face the Washington Senators. Perhaps because of the late notice, it wasn’t a packed house but a small crowd of about 10,000 who braved a brutal New York heat wave to come to Yankee Stadium to cheer his return.9

The Senators were 26-15 (second place) while the Yankees languished without Babe at a nearly opposite mark of 15-25 (next to last). Yankees fans were happy to see him though some observers felt he “really ought not to be in the contest” and was “still a sick man.10 Recently unearthed footage from the game shows him running at less than full strength, and looking thin, but still taking his trademark violent hacks at pitch after pitch.11

The starting pitcher for the Senators was the great Walter Johnson. It was his 19th season in the majors and the Big Train was still rolling. He led the league in wins, winning percentage, ERA, and shutouts the previous year. He was off to a strong 1925 as well, with a 7-2 record entering play despite having been hit hard his previous two starts. Starting for the Yankees was Sad Sam Jones, who gave up a leadoff double to Sam Rice (no mood given) to begin the game. Rice was stranded as Jones retired the next three hitters.

Johnson cruised through his half of the first and there was little excitement until Babe, batting fourth, stepped in to lead off the bottom of the second. Making his first plate appearance in the team’s 41st game of the year, he had to feel some rust. Johnson got him to tap weakly to the mound.

The score remained tied thanks in part to a nice play by the Yankees’ Earle Combs to rob Joe Harris of extra bases in the top of the third. In the top of the fourth, the Senators plated one, then the Yankees got one right back in their half. It was nearly a much bigger inning for New York as Ruth hammered a shot to deep right with Combs on first. The blast brought the crowd to its feet, but the ball veered foul by “just a foot or two.”12 Babe ended up walking. The next batter, Bob Meusel, hit a fly to deep center field that went past Rice for a double. Combs scored, but Ruth was thrown out at the plate, and it wasn’t close. It wasn’t pretty either. He reportedly “staggered,”13 then “landed with a thud, flat on his waistline — out by a foot.”14 It was noted that if he was able to run at full speed he likely would have scored standing up.

Despite his limited mobility, Babe was the star on defense in the fifth inning. There were two runners on when Joe Judge hit one in the gap in right-center. Ruth sprinted up the small hill that served as the warning track in Yankee Stadium. He leaped, snagged the fly, and though he tumbled to the ground, the ball remained in his glove. Center fielder Combs had to “help the fallen gladiator to his feet,” but the side was retired and the game remained tied, 1-1.15

The second physically painful play of the game and the brutal heat made it a tough day to return from a long absence. Yankees manager Miller Huggins sent Babe to the bench after the sixth for Bobby Veach. In the seventh the Senators cracked it open, scoring three runs. The big blow was a two-run triple by Goose Goslin. This gave Johnson a 4-1 lead, but he tired in the bottom of eighth, loading the bases on a double and two walks. Firpo Marberry came on in relief and retired the side without allowing a run to score, striking out Meusel on three pitches to end the inning. Notably, the second out of that inning was made by young Lou Gehrig, who had pinch-hit for Pee-Wee Wanninger. Wanninger, a light-hitting shortstop, was known for the fact that as a rookie he ended original iron man Everett Scott’s consecutive-game streak, a major-league record of 1,307 games some believed would never be topped.16 Yankees reliable first baseman Wally Pipp went 1-for-4 in the game. His average was .244, down from past years, and manager Huggins was considering a youth movement. He contemplated giving Gehrig — “the kid” — an extended look.17

In the top of the ninth, Washington leadoff man and star-of-the-game Rice got a one-out triple for his fifth hit of the day. The Yankees trailed 5-1 in the ninth when replacement shortstop Ernie Johnson hit a surprise two-run home run to right, cutting the lead to two. Johnson was followed by pinch-hitter Whitey Witt, who walked, bringing third baseman Joe Dugan to the plate. Jumping Joe represented the tying run and no doubt was the man Huggins wanted to see in this spot. Dugan was hot, with 44 hits in the month of May (30 games) and 21 hits in his last 12 games. Facing Marberry with the game on the line, he got good wood on the ball but hit it right at Senators second baseman Bucky Harris for the final out. The Babe was no doubt a little sore, physically, as well as disappointed in the way the game turned out, a 5-3 loss. But the big man showed that there was plenty of baseball left in him. He was very much alive, back, and hungry for more.

Notes

1 “Baseball Fans Get Shock: Idol of the Crowds Reported Dead.” Dundee (Scotland) Evening Telegraph, April 9, 1925.

2 “Washington Is Stirred: Early Morning Reports of Ruth’s Death Arouse Capital,” New York Times, April 10, 1925: 6.

3 Bill Ballew, “The Babe & The Bellyache: Babe Ruth, Asheville & McCormick Field | Asheville Tourists McCormick Field,” MiLB.com, undated. milb.com/content/page.jsp?sid=t573&ymd=20070425&content_id=232912&vkey=team1.

4 Dave Anderson and Alec Baldwin, The New York Times Story of the Yankees: 1903 — Present (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2017), 59.

5 Kal Wagenheim, Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974), 135.

6 Robert W. Creamer. Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 289.

7 Ibid.

8 “Ruth Is Discharged from Hospital,” New York Times, May 27, 1925: 19.

9 James R. Harrison, “Ruth Back in Game but Yankees Lose 5-3,” New York Times, June 2, 1925: 18.

10 “Babe Ruth Still a Sick Man, but His Spirit Is Unimpaired,” Washington Evening Star, June 2, 1925: 30.

11 Mike Axisa, “VIDEO: Rare Footage of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig from 1925,” CBSSports.com, CBS Sports, June 2, 2015, https://cbssports.com/mlb/news/video-rare-footage-of-babe-ruth-and-lou-gehrig-from-1925/.

12 Harrison: 8.

13 “Babe Ruth Still a Sick Man, But His Spirit Is Unimpaired.”

14 Harrison: 8.

15 Ibid.

16 Ray Birch, “Everett Scott,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/365591cd.

17 John Eisenberg, The Streak: Lou Gehrig, Cal Ripken Jr., and Baseball’s Most Historic Record (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 6.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 5

New York Yankees 3

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.