June 2, 1951: The return of the Miracle Braves in Boston

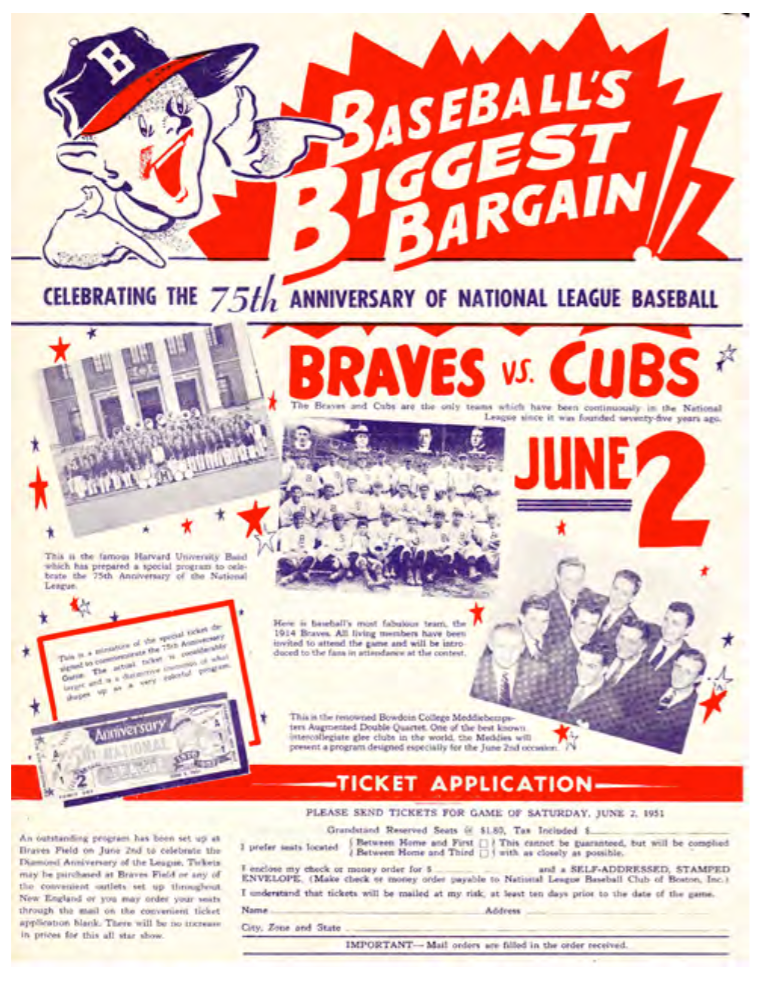

Special events were scheduled throughout the senior circuit season of 1951 to celebrate the league’s Diamond Jubilee 75th anniversary. National League ballclubs commemorated this historic event with a variety of ceremonies. The Boston Braves chose to bring back surviving members of the 1914 Miracle Braves World Series championship team as the Tribe’s jubilee contribution. A three-day affair was put together by Braves owner Lou Perini, culminating in pregame festivities at Braves Field before the Saturday, June 2 matchup with the visiting Chicago Cubs. Fittingly, Boston and Chicago were the only National League clubs to have operated continuously since the circuit’s formation in 1876.

Special events were scheduled throughout the senior circuit season of 1951 to celebrate the league’s Diamond Jubilee 75th anniversary. National League ballclubs commemorated this historic event with a variety of ceremonies. The Boston Braves chose to bring back surviving members of the 1914 Miracle Braves World Series championship team as the Tribe’s jubilee contribution. A three-day affair was put together by Braves owner Lou Perini, culminating in pregame festivities at Braves Field before the Saturday, June 2 matchup with the visiting Chicago Cubs. Fittingly, Boston and Chicago were the only National League clubs to have operated continuously since the circuit’s formation in 1876.

Time had taken its toll in the 37 years that had elapsed since the Braves’ last (and final) world championship. Eleven of the 34 ballplayers on the Tribe’s 1914 roster were now deceased. First to depart the scene was pitcher Otto Hess in 1926, followed in 1929 by manager George Stallings. The last survivor was utility infielder Jack Martin, 93, whose death closed this chapter of Miracle Braves history on July 4, 1980.

On Friday evening, the celebrants of Saturday’s jubilee events met in the Hotel Somerset lobby to reminisce with reporters. Asked what it was that led them on their triumphant march to the pennant, they cited team spirit. George Stallings’ deft leadership was duly noted. Pitcher Bill James stated, “We belonged in eighth place when we were there and without Stallings we belonged there at the end of the season.” Catcher Hank Gowdy seconded James’ opinion: “George made us a great team.” Even in 1951, old-timers grumbled about baseball’s changing salary structure. Staff ace and 1914 26-game winner James remarked that his largest contract was for $2,600 or about what he figured to be a week’s paycheck for Red Sox star Ted Williams.

First sacker Butch Schmidt entertained all with an anecdote of his own. He proclaimed that the Braves could have acquired Babe Ruth in 1914 from the International League Baltimore Orioles. Schmidt had played in Baltimore from 1908 to 1912 and was an acquaintance of club majority owner Jack Dunn. “I scouted Ruth myself when he was pitching for St. Mary’s Industrial School [and] recommended him to Gaffney when the Baltimore Orioles were breaking up,” Schmidt revealed. Dunn was under significant financial stress brought about by competition from the upstart Federal League Baltimore Terrapins who forced him to relocate his club to Richmond, Virginia, in 1915. (The Orioles returned to Baltimore in 1916, after the Federal League folded.) Schmidt claimed that for $10,000, Gaffney could have picked up not only the Babe but also pitcher Ernie Shore and catcher Ben Egan. However, Gaffney said “$10,000 was too much to pay for ballplayers.” Instead, the Red Sox jumped at the deal. Schmidt’s tale indicates that the “Curse of the Bambino” might have been cast upon not one but both of Boston’s baseball franchises!

Festivities kicked off on June 2 with a parade along Commonwealth Avenue to Braves Field. The old-timers assembled at the host hotel at noon for the trek to the Wigwam. Lou Perini and Ford Frick headed up the delegation, which was driven to the field in antique automobiles provided by Brookline’s Larz Anderson Museum. The procession commenced at 12:45 P.M. under the escort of the police and a detachment of US Marines. When the parade reached the Commonwealth Armory, it was joined by the almost 100-piece Harvard University band. As Harvard was in the midst of final exams, the bandsmen had to wear their uniforms to their tests. They then were given box lunches and hustled onto a bus that was driven to the Allston destination with the way cleared by members of the Cambridge police. Inside the armory nearly 3,000 Little Leaguers from Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island had assembled in uniform waiting to join the procession. Units from the Army and Navy added to the throng that entered the ballpark for the 1:15 kickoff of festivities. The Mutual Broadcasting Company was on hand to air the day’s special events and the ballgame to over 352 of its affiliates and to the armed forces overseas.

Festivities kicked off on June 2 with a parade along Commonwealth Avenue to Braves Field. The old-timers assembled at the host hotel at noon for the trek to the Wigwam. Lou Perini and Ford Frick headed up the delegation, which was driven to the field in antique automobiles provided by Brookline’s Larz Anderson Museum. The procession commenced at 12:45 P.M. under the escort of the police and a detachment of US Marines. When the parade reached the Commonwealth Armory, it was joined by the almost 100-piece Harvard University band. As Harvard was in the midst of final exams, the bandsmen had to wear their uniforms to their tests. They then were given box lunches and hustled onto a bus that was driven to the Allston destination with the way cleared by members of the Cambridge police. Inside the armory nearly 3,000 Little Leaguers from Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island had assembled in uniform waiting to join the procession. Units from the Army and Navy added to the throng that entered the ballpark for the 1:15 kickoff of festivities. The Mutual Broadcasting Company was on hand to air the day’s special events and the ballgame to over 352 of its affiliates and to the armed forces overseas.

The Diamond Jubilee celebration preceded the day’s Braves-Cubs contest at the Wigwam. Fans cheered as the parade of old-time automobiles circled the playing field, passing before the visiting and home dugouts. In each of the ancient jitneys was a member of the Marine Corps holding a sign that identified the honored guests in the buggy. Paraded before the crowd in addition to Gowdy, Mitchell, James, Smith, Schmidt, and Tyler were outfielder Herb Moran, catcher Bert Whaling, outfielder Les Mann, third baseman Charlie Deal, pitchers Dick Crutcher and Paul Strand, batboy Willie Connors, and George Stallings, Jr., substituting for his father. Instead of donning replicas of their ’14 togs, the guests appeared in current Tribe tomahawk-style uniforms.

Each of the old-timers was called out onto the field by National League President Ford Frick to assume his former position. Mitchell and Stallings Jr. reported to the first- and third-base coaching boxes, respectively. Gowdy and Whaling, catcher’s mitts in hand, stood behind home plate. James, Tyler, and Crutcher took to the mound while Schmidt and Smith ambled to first and third base. Deal subbed for the late Johnny Evers at second base while Messrs. Mann, Strand, and Moran walked to their outfield positions. The placement of pitcher Strand in the outfield was not entirely out of place as an accommodation to the dearth of reunion representatives at that position. In 1915 he appeared in five games in the outfield for the Braves in addition to performing his normal mound duties, and finished his career as a fly chaser. As would be expected, batboy Willie Connors was situated on the sidelines.

Fan favorite Rabbit Maranville drew the day’s greatest ovation as he was introduced and jogged to his position at shortstop. The diminutive infielder had missed the parade as he had had to make a quick trip to New York to fulfill a commitment to a sandlot baseball group. Flying back to Boston on Lou Perini’s private aircraft, he rushed from the airport in time to dress and just make it to the Wigwam for the introductions. Maranville “warmed up” by taking a few groundballs, flipping one behind his back to Deal at second. When announcer Les Smith informed the crowd that the irrepressible Rabbit would perform his legendary “vest pocket” catch, a roar came from the stands. Hank Gowdy threw a ball high in the air toward the peppery shortstop and Maranville gingerly backed up toward left field, cupped his hands and caught the ball at belt level to the delight of all. Rabbit then twisted his cap sideways on his head as he had done throughout his playing days.

Watching the day’s events and the game from the stands was 91-year-old C.A. Brown who claimed to have been present at Boston’s first National League game on May 30, 1876. Unfortunately, he and the other 15,127 in attendance witnessed the Braves go down to defeat, 7-5, despite some ninth-inning attempted heroics. Tribe starter Warren Spahn had one of his infrequent poor outings, lasting less than two innings, yielding four runs on six hits and two walks. Earl Torgeson provided some excitement, blasting an eighth-inning two-run homer, five rows into the Jury Box. Cubs “senior citizen” reliever Dutch Leonard squelched a rally in the bottom of the ninth, retiring the side after coming in with no outs and two Braves on base.

Seated behind home plate during the game, the “Miracle Men” couldn’t help but contrast “Stallings’ baseball” against the current version. At one point when the Braves filled the bases and the next batter swung at the first pitch and hit into a double play, Bill James reflected, “Under Stallings, the batter wouldn’t swing at the first pitch. Maybe the pitcher would have walked the next man up and forced in a run.” James remarked that Stallings always said, “Let the pitcher lick himself, if possible.” Les Mann and Red Smith both observed, “We won the pennant in 1914 by bunting. It’s a different game today.” The old timers got caught up in the excitement of the last-inning rally and later expressed their appreciation to the present-day Braves for trying pull out a win for them.

Despite all of the hoopla surrounding the celebration, the turnstile figures were disheartening, especially when one considers that the grand total was a bit “padded.” Passes were handed out to the 2,985 Little Leaguers, 157 servicemen, and 2,001 Knothole Gang members, leaving just 9,984 paying guests. The lukewarm reception drew an editorial rebuke in the June 13 issue of The Sporting News. Baseball’s “Bible” expressed disappointment toward the fans’ “So what?” reaction to the jubilee commemoration and honoring of the game’s pioneers. As the TSN editorialist opined, “The game owes a great deal to these old-time heroes, whose achievements helped the majors over a period of struggle and made possible the sport’s present solid place in American life.”

The original extended version of this piece appeared in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions“ (SABR, 2014) and it is also included in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN195106020.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1951/B06020BSN1951.htm

Photo credits

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.