June 25, 1914: Buffalo and the sheriff greet Hal Chase on his ‘day’ at Federal League Park

The Buffalo Buffeds1 were already 10 weeks into their first season,2 but along with other members of the upstart Federal League, they were still trying to fortify their respective lineups with players willing to walk away from their American and National League teams and “jump” to contracts in the Federal League.

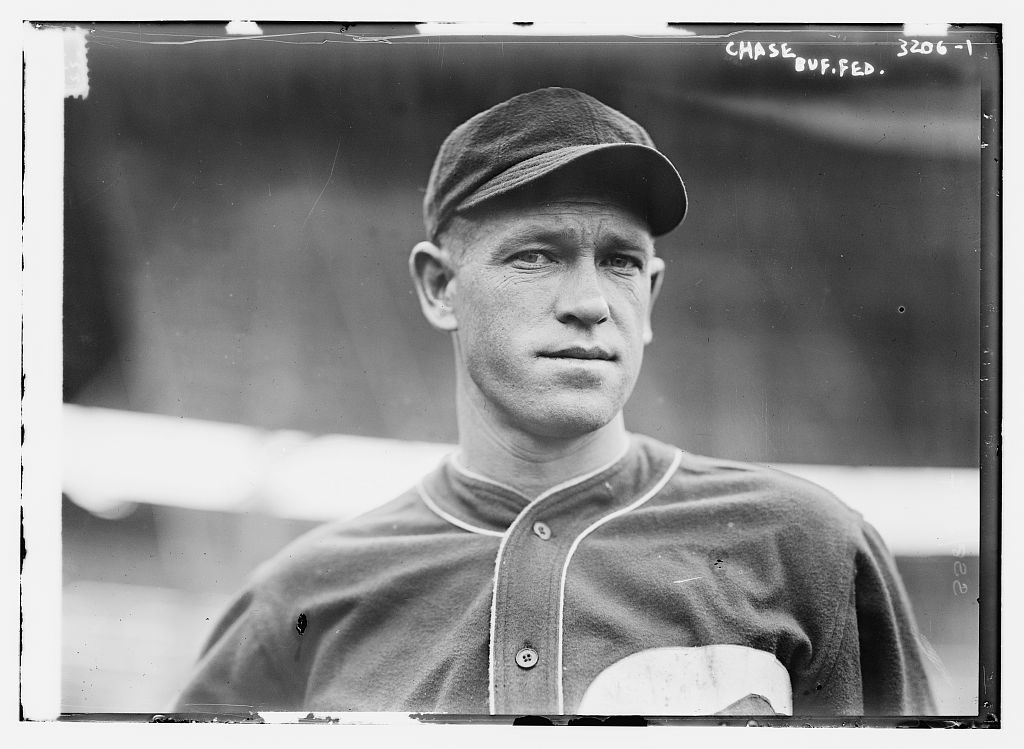

One of the prime targets for Buffeds club secretary John L. Kelly was Hal Chase, the smooth-fielding first baseman for the Chicago White Sox. Chase, a known purveyor of what might today be termed bad clubhouse chemistry, but who was sometimes called “the greatest first baseman in the world,”3 had worn out his welcome with the New York Yankees in 1913, and had been traded on June 1 to Chicago for “two ordinary men.”4

There, Chase had continued to be a distraction among his teammates and was receptive to the “princely sums” being offered to leave Organized Baseball for the Federal League.5 After playing first base for the White Sox on Saturday, June 20, 1914, in a 5-2 win over the Red Sox at Comiskey Park in which he went hitless with a walk, Chase signed with the Buffeds that evening. Buffalo was in town playing the Chicago Federal League entry, the Whales,6 so Chase suited up the next day, Sunday, June 21, as a Buffed at Weeghman Park7 on the Chicago Near North Side. Playing first base and batting fifth for Buffalo, he singled, doubled, and drove in the Buffeds’ only run in a 2-1 loss.

On Monday, June 22, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey sought and obtained a preliminary injunction against Chase’s playing baseball as a member of any team except the Chicago American League club. While the Buffeds remained in Chicago for games that day and Tuesday, June 23, winning one and losing one, secretary Kelly immediately spirited Chase and his wife out of Chicago to avoid legal service of the injunction on the prized new first baseman. On arrival back in Buffalo, Kelly orchestrated “highly amusing antics”8 to foil service, with a promotional eye to having Chase on the field when the Buffeds returned home for a game against the Pittsburgh Rebels on Thursday afternoon, June 25. The Chases were promptly “hustled to parts unknown,”9 which turned out to be across the international border into the Niagara area of Ontario.

Freshly arrived from Chicago, secretary Kelly told Buffalo reporters that the club would celebrate Chase’s acquisition with “Hal Chase Day” in conjunction with the Buffeds’ return home, guaranteeing that “Chase will positively play first base,” on June 25.10 “Something similar to a holiday crowd is expected to take in the game, with Kelly promising ‘a booklet containing a photograph and biography of the star first sacker [being] given to those who pass through the gates.’”11

The Buffeds’ skulduggery continued as Mrs. Chase traveled separately back to the United States, then, just before game time — with Comiskey’s injunction still unserved — Hal Chase was brought by a circuitous route to the Buffalo Country Club. There “he remained long enough to dress up in female attire.12 Then he was taken to the Fed grounds13 and kept under cover in a toolhouse until it was time to start [the] game.”14 The club had even looked into hiring an “aeroplane” as part of their plan, but “[their] request by long distance ’phone was too late, as [they] could not get a machine until Saturday.”15

The Buffeds had also come up with a game-day ploy to frustrate service of the injunction before Chase could make a triumphant appearance as the newest member of the team — manager Larry Schafly advised umpires Barry McCormick and Ed Goeckel that Buffalo would exercise its option as the home team to bat first.16 Ideally, Chase could get a quick at-bat before he could be served. And the Buffeds’ legal eagles had yet another trick up their sleeve that bought additional time. They convinced the deputies — possibly Buffeds fans — that proper service could be made only by Erie County Sheriff Fred Becker himself, who was not with the deputies when they arrived.

With this maneuvering in place, the game, scheduled for 3:30 p.m., started a half-hour late17 with 6,443 fans in the stands.18 Pittsburgh starter Howie Camnitz, himself a Federal League signee from Organized Baseball,19 disposed of Frank Delahanty.20 Batting second in the order, Chase, “given a great ovation,”21 then stepped in but “in a fit of pardonable nervousness,” he struck out.22 Chase played first base without incident as Pittsburgh failed to score in the bottom of the first. He watched teammate Charlie Hanford lead off the Buffalo second inning with a home run to left field to open the scoring.23 Buffeds starter Earl Moore24 kept the lead at 1-0 as the Rebels batted in the bottom of the second, with Chase still manning first base for the Buffeds.

At that point, though, Sheriff Becker arrived, personally served the injunction on Chase in what the Buffalo Evening News described as an exchange accepted by “the world’s premier first baseman” with a smile, after which Chase “walked to the players’ bench, there to remain.”25

He saw his teammates immediately erupt to put the game away in the third inning. Walter Blair opened with a single; the Rebels threw away Moore’s bunt, and Delahanty singled in a run. Joe Agler, taking over for Chase, bunted and Pittsburgh erred again to load the bases. Baldy Louden singled in another run before the Rebels managed to get the first outs on a 9-to-2 double play — it took a “perfect throw” from Bob Coulson in left field to double up Delahanty at the plate on Hanford’s fly ball. Even for Deadball Era, baseball things may have still been manageable at 3-0, but Agler and Louden had moved to third and second on the play at the plate, and Camnitz did himself in, allowing a two-run single by Everett Booe “along the left field foul line.”26

Pittsburgh closed to 5-2 in the sixth inning on Menosky’s single, a walk to Coulson and a boot by Buffeds shortstop Louden that left the ball languishing in left-center field as two runs scored. Buffalo completed the scoring in the top of the ninth without benefit of a hit as a walk, stolen base, and Rebels catcher Claude Berry’s two-base throwing error delivered Buffalo’s sixth run.27 Moore finished off Pittsburgh in the bottom of the ninth to wrap up a two-hitter that, absent Louden’s error, could well have been a shutout. Even with the Hal Chase hoopla and service of the injunction, everything was wrapped up in an hour and 40 minutes.

With the temporary injunction finally served, Chase couldn’t play until a court determined whether there would be the permanent ban Comiskey and Organized Baseball wanted. Chase bided his time by looking at a potential farm purchase in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and playing in at least one semipro baseball game.28 Meanwhile, the wheels of justice rolled on. The injunction case had been assigned to Justice Herbert P. Bissell of the Sixth District of the New York Supreme Court, sitting in Erie County. He scheduled a hearing on the injunction for July 6, then continued it until July 9.29

Extensive presentations by the attorneys for both sides carried the hearing over to July 10. The Buffalo Enquirer presciently noted that “a new point raised in the Chase case by the Feds’ lawyer is that the contract between the Chicago White Sox and the first sacker lacked mutuality,” relating to the presence of a clause in the standard player contract giving his club the right to terminate service on 10 days’ notice without extending the same right to the player.30

And although Justice Bissell’s 25-page opinion, issued on July 21, touched on the many facets presented during the two days of legal argument, he dissolved the injunction on the mutuality point, writing: “The contract, being unilateral, lacks mutuality in that the employer having the right to terminate the contract [on 10 days’ notice], the employee is remediless.”31

Hal Chase was now legally free to play baseball for the Buffeds, and he got right to it.32 On Wednesday July 22, the day after Justice Bissell dissolved the injunction, he was back at Buffalo’s Federal League Park, batting cleanup against the visiting Kansas City Packers.33 He went hitless with a walk, but the Buffeds won, 6-3, as emery-ball specialist Russ Ford34 closed out the final one-third of an inning with the bases loaded and two outs.

Buffalo had been 27-23 through June 20, when Chase played his first game with them in Chicago. With the injunction in place from June 22 through July 21, they won 12 and lost 16. From July 22 through the end of the season, with Chase hitting .347 and driving in 47 runs in 297 plate appearances, they improved to 41-32. The Buffeds finished the 1914 Federal League season at 80-71, good for fourth place, seven games behind the pennant-winning Indianapolis Hoosiers.35

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for box scores, player, team, and season pages, and batting and pitching logs.

Notes

1 Buffalo’s Federal League franchise was also sometimes known as the Blues, their designation at Retrosheet. Baseball Reference uses the “Buffeds” designation in its box scores; except for quoted material, that designation will be used throughout this account to avoid confusion. Contemporary newspaper reports sometimes also referred to the team as the “Buf-Feds.” Buffalo was also the home of the Bisons, a minor-league team, in the 1914 International League. The city’s professional baseball history dates to 1877, when an unclassified team represented Buffalo in the League Alliance. Buffalo fielded an original National League franchise, also called the Bisons, from 1879 through 1885, and a Players (major) League team in 1890, that league’s only season. The city has been represented by minor-league Bisons teams at varying classification levels, most often in the top-level, AA, then AAA, International League, continuously since 1891.

2 The Federal League played a 120-game schedule with six teams in 1913, but did not declare itself to be a “major league” until the 1914 season. Buffalo did not have an entry in the 1913 Federal League. Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011), 20.

3 William Peet, “Chase Is Traded to Chicago White Sox,” Washington Herald, June 2, 1913: 8. In his comprehensive history of the Federal League, SABR member Robert Wiggins (See: Note 2) opines: “If it were not for his unsavory reputation, Hal Chase would be in Baseball’s Hall of Fame.” Wiggins, 128.

4 “Chase Is Traded.” During his tenure in New York, Chase used a threat to leave the team to gain a midseason raise in 1907. In 1908 and again in 1910, he actually left the team for brief periods. Martin Kohout, “Hal Chase,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed May 15, 2018. See: “Harold Chase’s Baseball Career,” Buffalo Enquirer, May 15, 1915: 6, concerning the 1908 incident, for which Chase was briefly suspended by AL President Ban Johnson.

5 “Feds Are Planning for Another Raid,” Evening Sun (Baltimore), June 16, 1914: 5. Baseball Reference reports Chase’s 1914 salary with the White Sox as $6,000, the same amount he was paid by the Yankees in 1913. The same source reports his 1914 salary with Buffalo as $9,000.

6 Baseball Reference alternatively uses Chi-Feds and Whales to refer to Chicago’s Federal League franchise. Retrosheet sticks with Chi-Feds.

7 Owner Charles Weeghman built the ballpark for his Federal League team. The edifice has lasted considerably longer than the Federal League, which folded after the 1915 season. The former Weeghman Park is now known as Wrigley Field, and has been the home of the Chicago Cubs since 1916.

8 “Organized Baseball Claims Victory, So Do Feds, in the Hal Chase Case,” Buffalo Commercial, June 26, 1914: 7.

9 “ ‘Buf-Feds’ and Hal Chase Due For a Big Welcome Today,” Buffalo Courier, June 25, 1914: 12.

10 “Thursday Will Be ‘Chase Day,’” Buffalo Evening News, June 23, 1914: 15.

11 Ibid.

12 “That afternoon,” wrote the editor of The Sporting News, “they dressed Chase in his wife’s clothing and slipped him into the park as a dashing widow — or maid.” The Buffalo Express commented that “Hal made a very pretty looking girl — heavily veiled.” Wiggins, 130-31.

13 Like some others in the new Federal League, Buffalo’s ballpark was known simply as “Federal League Park.” It was a new facility, seating 20,000, located at the corner of Northland Avenue and Lonsdale Road. “Federals Get Away Today,” Buffalo Morning Express, May 11, 1914: 1. Buffalo had played 17 consecutive road games against five Federal League opponents from April 13 through May 9 before their home opener on May 11. Despite intermittent rain and cold temperatures, the opener drew 14,286 fans. “14,000 in Rain See Buf-Feds Lose, 4-3,” Buffalo Courier, May 12, 1914: 1.

14 “Organized Baseball Claims.”

15 Special Wire to the Courier, datelined Hammondsport, New York, quoting Buffeds’ club President W.E. Robinson: “Wanted Aeroplane to Carry Hall Chase to Federal Field,” Buffalo Courier, June 25, 1914: 12.

16 “Although we now take it for granted that the home team bats last, this was only formalized in the rules in 1950. Prior to that, it was the home team’s option.” David W. Smith, The Retro Sheet, Volume 5, No. 3, September 1998, retrosheet.org/newslt14.txt, accessed April 9, 2018.

17 Wiggins, 131.

18 Despite the hoopla, it was a Thursday afternoon. It was, though, one of the better home crowds Buffalo had in 1914, according to the partial game-by-game attendance information preserved at Baseball Reference. The Buffeds had drawn 15,297 for a Memorial Day doubleheader against these same Rebels, and 8,580 on Saturday, May 16, against the Chicago Whales. The home opener back in May had drawn 14,286 in bad weather. See: Note 13.

19 Camnitz pitched in the National League with the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1904 through August 1913, when he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. He signed with the Pittsburgh Federal League club in January 1914.

20 Frank “Pudgie” Delahanty was one of five Delahanty brothers, along with Tom, Joe, Jim, and most prominently, Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty, to play professional baseball. Frank had last played with the New York Highlanders (Yankees) in 1908 before becoming a Buffed in 1914.

21 “Earl Moore Defeats Rebels on Two Hits,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 26, 1914: 12. Wiggins writes that Chase didn’t come out of the toolhouse until Delahanty had stepped in to bat. Wiggins, 131.

22 “Umpire Becker Puts Hal Chase Out in Second,” Buffalo Evening News, June 16, 1914: 15.

23 Ibid.

24 Moore, a right-hander, was 36 years old and had been in the major leagues since 1901. He had pitched with the Cubs and Phillies in the National League in 1913.

25 “Umpire Becker.”

26 “Earl Moore.” The Post-Gazette game story (Note 21) credits right fielder Mike Menosky with the “perfect throw,” and the accompanying box score credits him with an assist. The Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet box scores show Coulson with an assist in the game but not Menosky.

27 Ibid.

28 “Hal Chase Performs at Ann Arbor but Fails to Get a Hit,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, July 20, 1914: 5.

29 The Sporting News, July 9, 1914: 1.

30 Edward Tranter, “Comments on Live Sports Topics,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 10, 1914: 6. Probably with legal guidance, Chase had nonetheless given 10 days’ notice to Comiskey before he signed with Buffalo.

31 Victory for the Federals,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 21, 1914: 1.

32 Comiskey and the American League attorneys filed an immediate notice of appeal. Buffalo Courier, July 22, 1914: 8. Nothing came of it. A reason may have been that the 1914 White Sox proved they could lose with or without Chase’s distractions. When he jumped to Buffalo after the June 20 game, they stood 26-31 (.456), in sixth place in the AL. Over the rest of the season they were 44-53 (.454), finishing in seventh place at 70-84.

33 This time, Chase didn’t need female attire or the toolhouse, and Buffalo batted last.

34 Wiggins, 97.

35 Apparently happy with his 1914 experience as a Buffed, Chase returned for Buffalo’s second and last Federal League season in 1915, leading the soon-to-fold circuit with 17 home runs. Surprisingly, management did not repeat Hal Chase Day in Buffalo in 1915, although at least one local sportswriter proclaimed him “the greatest player who ever wore a Buffalo uniform.” “Harold Chase’s Baseball Career,” Note 4.

Additional Stats

Buffalo Buffeds 6

Pittsburgh Rebels 2

Federal League Park

Buffalo, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.