June 7, 1884: Charlie Sweeney strikes out 19 for Providence

Providence, Rhode Island, was an awfully small city for two egos as big as those of Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn and Charlie Sweeney, the starting pitchers for the hometown Grays in 1884. As early as spring training the surly veteran Radbourn, a wily strategist from Bloomington, Illinois, and the boastful young Sweeney, a blunt power pitcher from San Francisco, had become “jealous of each other,” the New York Times observed, and a month of harsh regular-season play had failed to burn away their hostility.1

Providence, Rhode Island, was an awfully small city for two egos as big as those of Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn and Charlie Sweeney, the starting pitchers for the hometown Grays in 1884. As early as spring training the surly veteran Radbourn, a wily strategist from Bloomington, Illinois, and the boastful young Sweeney, a blunt power pitcher from San Francisco, had become “jealous of each other,” the New York Times observed, and a month of harsh regular-season play had failed to burn away their hostility.1

So when Radbourn pitched all 16 innings of a brilliant 1–1 tie on June 6 in Providence against the defending National Leagues champion Boston Beaneaters—a “phenomenal game, the like of which will probably never be seen again,” the Providence Journal raved—Sweeney knew he had to do something special to win back the city’s attention and applause.2

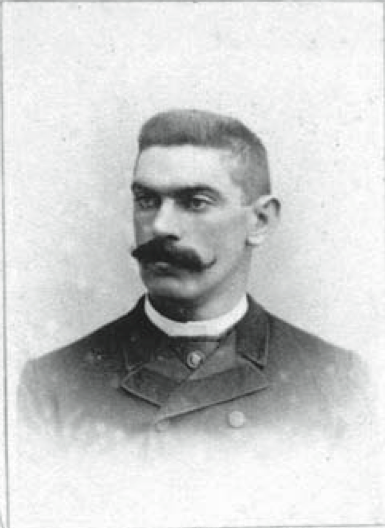

June 7 was the kind of late-spring day that made New England hearts soar—sunny, warm, and breezy—and a fine Saturday crowd of 7,387 thronged Boston’s South End Grounds, the rotting wooden ballpark crammed in between Columbus Avenue and several sets of railroad tracks. In a feat of bravado, even for 1880s pitchers, Boston Beaneaters ace Jim “Grasshopper” Whitney worked again after pitching 16 innings the day before, and he was superb, allowing only two runs and six hits while striking out 10. But Sweeney, a 21-year-old right-hander with a square jaw and burning, wide-set eyes, was stoked to pitch one of the greatest games in major-league history. That was clear from the moment the 5-foot-10, 181-pound Californian stepped into the 6-by-4- foot pitcher’s box.

“Outs and ins, drops and rises seemed to be all the same to Sweeney,” the Boston Globe reported. “He could give them all, and pitched some of the most deceptive curves imaginable.”3 The son of Irish immigrants was “in magnificent form, and he pitched with such remarkable strategy and speed that Boston’s heavy hitters were forced to go down before him one after another,” the Providence Journal wrote.4

He struck out five of the first six batters who faced him—all without the modern advantage of foul balls being strikes. Eight of Sweeney’s first nine outs were strikeouts. After six innings, he had mowed down 14 men. Providence broke a 0–0 tie in the fifth, when Boston center fielder Jack Manning juggled a fly, permitting the Grays’ Arthur Irwin to scoot in from third. But Manning more than made up for it moments later, catching a line drive at full sprint and firing the ball to first to double up the runner there. When Boston captain and first baseman John Morrill whipped the pill across to third to catch the Grays’ Jerry Denny sliding in there, the Beaneaters had pulled off a stunning triple play. “Immediately there was the wildest excitement and confusion,” the Globe reported. Men threw their hats in the air, women flashed smiles and waved handkerchiefs, and everyone carried on joyfully.

In the seventh inning, after the Grays had taken a 2–0 lead, Sweeney surrendered a walk to Whitney— though the Journal was certain it should have been another strikeout, since in the reporter’s eyes Charlie split the plate five times. The Grasshopper later scored on an error, to cut the lead to 2–1.

As the ninth inning opened, the crowd exhorted the Beaneaters to close the gap. But the real story was Sweeney’s astounding performance. With his zipping fastball and biting curve, he was smashing the major-league strikeout record. Sweeney whiffed Morrill, a very tough out, for strikeout number 17. Manning, next up, swung “at the sphere as if he would lift it over the centre-field fence, but only empty air met the willow, and he, too, retired on strikes.” Bill Crowley, a 27-year-old from Philadelphia who would hit .270 that year, stepped into the right-handed batter’s box, and stared down Sweeney. But it was no match, as Crowley whiffed to end it. The mighty crowd, silent for most of the day, erupted in cheers for the visiting pitcher’s astonishing feat. “NINETEEN STRUCK OUT; Sweeney’s Mysterious Curves Baffle Boston’s Batters,” read the Globe’s headline the next day. “It was “a record,” the Journal predicted, “which will not be broken in many a day.” Hugh “One Arm” Daily officially tied it, on July 7, but that was against vastly weaker competition, the Boston Reds of the hapless Union Association, whose very status as a major league has been sharply questioned by such savants as Bill James.5 But it wasn’t officially broken until more than a century later, on April 29, 1986, when another bigheaded young man posted a 20-strikeout masterpiece in Boston. His name was Roger Clemens.

Alerted by telegraph, Providence leaders rushed to provide a grand welcome home. When the Grays arrived at Union Depot at 7:45 p.m., horse-drawn carriages and Herrick’s Providence Brigade Band were waiting. Men plucked up Sweeney and carried him on their shoulders to his carriage, the band struck up “Hail to the Chief,” the lesser players piled in, and the triumphal parade set off from the station. Colored flares lit up a dusky sky thick with coal smoke. The “streets were one vast blaze of red fire and the crowd packed the sidewalks thicker than sardines,” Sporting Life reported.6

One observer who clearly did not share in the delight was Radbourn. His incessant brooding about the man of the hour, the focus of the accolades, the arrogant Sweeney, led to a rupture in the club later in the season—and to the most brilliant sustained pitching performance in history, as Old Hoss, working virtually alone, day after day, went on to win 60 games.

But that was ahead. For weeks after the June 7 masterpiece, the crowd at the Messer Street Grounds taunted Radbourn, “nagging him to ‘break the record’ ” that Sweeney had set. Not surprisingly, this was said to bother the proud veteran “exceedingly.”7

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 “Ball Players Who Won’t Play,” New York Times, July 23, 1884.

2 Providence Journal, June 7, 1884.

3 Boston Globe, June 8, 1884.

4 Providence Journal, June 9, 1884.

5 Bill James, “State of the Union,” The New Bill James Historical Abstract (Free Press, New York, 2001), p. 21-22.

6 Sporting Life, June 18, 1884.

7 Fall River Daily Evening News, September 5, 1884.

Additional Stats

Providence Grays 2

Boston Beaneaters 1

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.