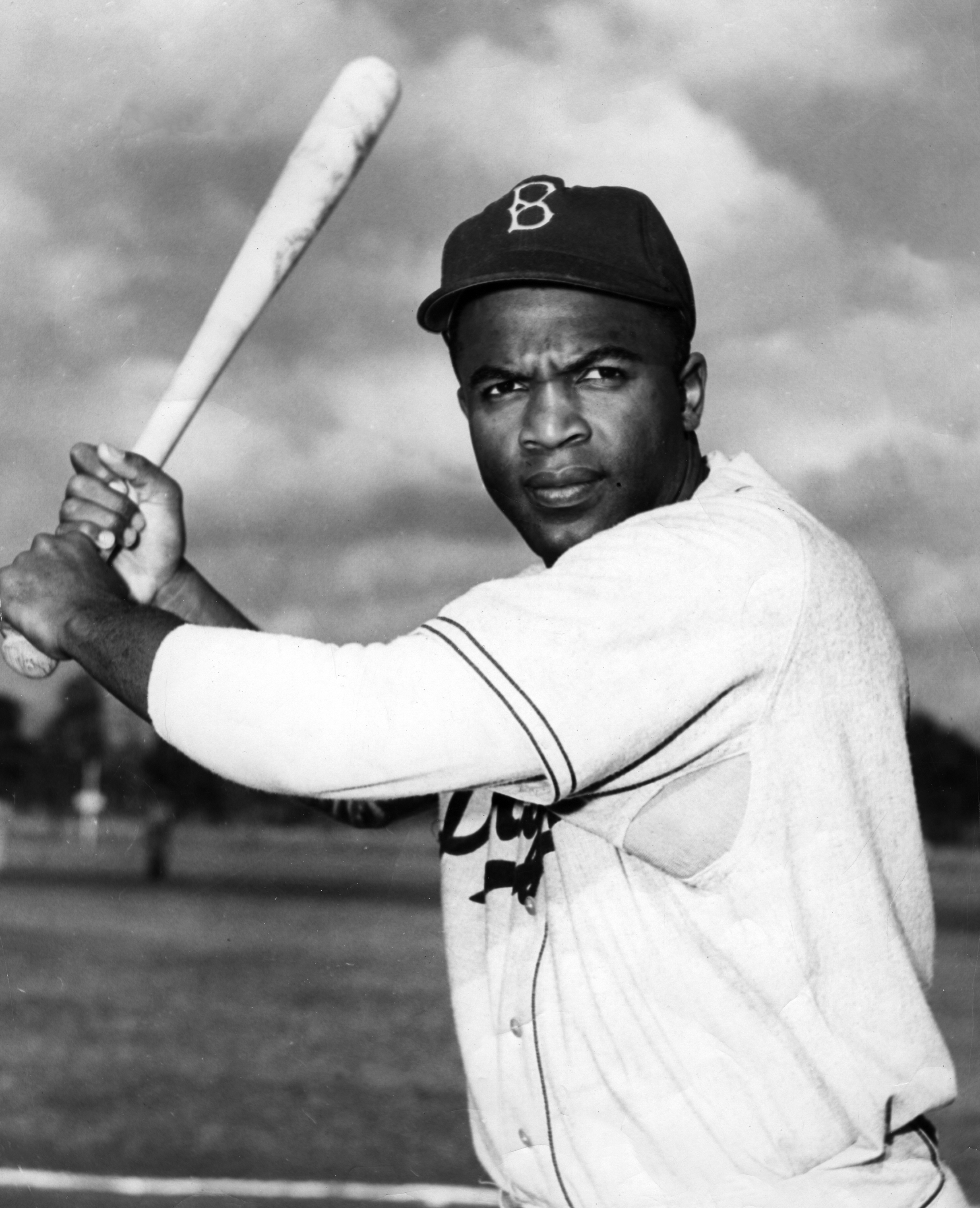

May 21, 1947: Jackie Robinson makes his Dodgers debut in St. Louis

Jackie Robinson never thought the abuse would happen in New York City. He was accustomed to receiving this kind of racial vilification — the vitriol and vulgarity heaped on him simply because of the color of his skin — in the Jim Crow South, where blacks, if not inured to the humiliation, at least knew it was coming, and how to tolerate it. Not here, however. Robinson never expected it in the north, in one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities.

Jackie Robinson never thought the abuse would happen in New York City. He was accustomed to receiving this kind of racial vilification — the vitriol and vulgarity heaped on him simply because of the color of his skin — in the Jim Crow South, where blacks, if not inured to the humiliation, at least knew it was coming, and how to tolerate it. Not here, however. Robinson never expected it in the north, in one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities.

Yet, there it was: every conceivable racial slur leveled at this proud man; every despicable, deplorable invective one could imagine, pouring forth from the Philadelphia Phillies dugout, each time Robinson took the field at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Yes, he had agreed to keep his anger in check, to turn the other cheek. Robinson had given Branch Rickey his word that he would not fight back. How much was one man expected to take, though, when every fiber of his being cried out for him to stride to the Phillies’ bench and, as Robinson recalled years later, “grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist.”?1

That day, April 22, 1947 (as well as the remaining two games of the three-game series), as the Phillies’ manager, Ben Chapman, a Southerner, led the torment of Robinson from the Phillies dugout, has been endlessly chronicled in the years since Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. With each telling of the narrative, it is perhaps the most infamous and notorious example of the vicious treatment Robinson endured that season, as he integrated modern baseball. Indeed, Robinson himself later conveyed his sense of desperation at the time, relating in his autobiography that although “I tried just to play ball and ignore the insults,” the Phillies’ racist taunts left him “tortured” and “brought me nearer to cracking up than I ever had been.”2 It was a shameful and disgusting display of man’s inhumanity toward man.

If that Phillies series, however, marked the nadir of Robinson’s degradation, it also formed cohesion among the man and his teammates; even, to a degree, those who shared the same views as did the Phillies’ racist manager. As Branch Rickey opined years later, “Chapman did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers.”3 For as the other Dodgers witnessed the abuse Robinson was taking, a solitary figure unable to fight back, many began to sympathize with his plight and to stand up for him — to see him, simply, as a man. Perhaps they weren’t all to become instant friends, and perhaps Rickey would have to defend Robinson against those Dodgers who refused to fully accept a black man, but as the season went on, Robinson became one of theirs, and they gradually learned to live with each other. That Robinson was possessed of undeniable talents assuredly made his presence that much easier to take.

As important as it was for Robinson to gain acceptance within the clubhouse, it was equally important that he be accepted outside as well. In that, he had a most effective advocate: The sporting press was critical in humanizing Robinson and generating empathy in the eyes of the mostly white public. And no single reportage was more important than an exclusive that was published by the New York Herald Tribune’s legendary sports editor, Stanley Woodward.

In his autobiography, Robinson incorrectly remembered that Brooklyn was scheduled to make its first visit to St. Louis, baseball’s southernmost city, where he was certain to receive his most vehement abuse, on May 9, 1947. In actuality, though, it wasn’t until May 21 that the Dodgers and Cardinals met for the first time in St. Louis. Just before that date, however, Woodward discovered that the Cardinals players were plotting to execute a last-minute strike in protest of Robinson’s inclusion on the Brooklyn squad. Woodward printed the story. The ramifications of the exposed plot were immediate.

“If you do this,” warned National League President Ford Frick, “you will be suspended from the league. You will find that the friends you think you have in the press box will not support you, that you will be outcasts. I do not care if half the league strikes. Those who do it will encounter quick retribution. They will be suspended and I don’t care if it wrecks the National League for five years. This is the United States of America, and one citizen has as much right to play as another.

“The National League will go down the line with Robinson whatever the consequences. You will find if you go through with your intention that you have been guilty of complete madness.”4

The Cardinals’ planned strike was never carried out.

Against that backdrop, on Wednesday afternoon, May 21, the Dodgers and Cardinals took the field at Sportsman’s Park. The struggling Cardinals had the worst record in the majors (9-18), while the Dodgers (14-13) were in fifth place, 1½ games behind the Chicago Cubs. Despite the game’s racial overtones, the Cardinals front office likely breathed a sigh of relief that the strike hadn’t taken place, because the 16,249 fans in attendance that day were the Cardinals’ largest weekday crowd thus far in the season. That number included, reported the press the next day, an estimated “6,000 Negroes.”5 Starting for the Cardinals was left-hander Harry Brecheen, who came in with a 4-1 record, picking up where he left off as the pitching star of the previous fall’s World Series. Batting second for Brooklyn and playing first base, was Robinson. Fittingly, he was to be instrumental in the game’s final outcome.

In their first at-bats, Brooklyn struck quickly. That a Cardinals defensive blunder helped must certainly have exacerbated the chastened Cardinals’ undoubtedly already surly dispositions. After leadoff batter Eddie Stanky flied out, Robinson drew a walk and quickly advanced to third on a single by Pete Reiser. The next batter was Carl Furillo. Playing first base for St. Louis was Stan Musial. As Brecheen delivered, Furillo hit a hard grounder to Musial, so hard, that Robinson could not advance. That quickly changed, however. Fielding the ball cleanly, Musial stepped on first, but then made an ill-advised decision. As Reiser bolted for second, Musial ignored Robinson and fired a throw to second, where shortstop Marty Marion awaited. Because Musial had stepped on first, Marion had to tag Reiser, but Musial’s throw was low and wide, and Marion failed to hold on to the ball. On the throw, Robinson trotted home, giving the Dodgers a 1-0 lead as the inning ended. It was to be a critical run.

For posterity, history records that the Dodgers went on to win this game 4-3, in 10 innings, when Cookie Lavagetto singled home Reiser in the top of the 10th. The victory ran their record to 15-13, a modest start on their way to the National League pennant, with a 94-60 record. They couldn’t have done it without Jackie Robinson, though. After finishing the season with a .297 batting average and a league-leading 29 stolen bases, the 28-year-old Robinson was named the league’s Rookie of the Year. Two years later he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player, and by the time he retired after the 1956 season, he had cemented his legend as a baseball immortal, and perhaps the most transformative athlete in the history of sports.

That the Dodgers won this, their 28th game in a long 154-game season, and that Robinson, despite going 0-for-4, contributed to the victory, was certainly important. Of far greater importance, however, was the fact that here, in the South, this black man “was cheered each time he went to bat and the Dodgers as a team received more vocal encouragement than they usually [got] at Sportsman’s Park.”6

In the end, no one could have synopsized that season better than Robinson himself. In his autobiography, Robinson wrote eloquently: “I had started the season as a lonely man, often feeling like a black Don Quixote tilting at a lot of white windmills. I ended it feeling like a member of a solid team. The Dodgers were a championship team because all of us had learned something. I had learned how to exercise self-control — to answer insults, violence, and injustice with silence — and I had learned how to earn the respect of my teammates. They had learned that it’s not skin color but talent and ability that counts. Maybe even the bigots had learned that, too.”7

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson (New York: Harper Collins, 1972), 69.

2 Ibid.

3 Robinson, 72.

4 Robinson, 73.

5 J. Roy Stockton, “Cardinals ‘Health Resort’ Makes Rivals Feel Better, Fans Worse,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 22, 1947: 10C

6 Ibid.

7 Robinson, 75.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 4

St. Louis Cardinals 3

10 innings

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.