October 5, 1913: Frank Wickware wins barnstorming battle between the Big Train and ‘Black Walter Johnson’

In 1913 baseball’s popularity was unchallenged in America. It seemed as if every town had multiple amateur and semipro teams vying for local bragging rights. Given that baseball was a segregated sport at the time, it is a wonder that a professional, independent Black team like the Schenectady Colored Mohawk Giants would thrive in an almost all-White community.

In 1913 baseball’s popularity was unchallenged in America. It seemed as if every town had multiple amateur and semipro teams vying for local bragging rights. Given that baseball was a segregated sport at the time, it is a wonder that a professional, independent Black team like the Schenectady Colored Mohawk Giants would thrive in an almost all-White community.

Bill Wernecke, a former semipro outfielder and an employee of General Electric, which had a large presence in Schenectady, had obtained a lease to Island Park, Schenectady’s premier baseball site, in 1912.1 Located on an island in the middle of the Mohawk River, Island Park could be accessed only by a gutsy walk over an “active” pontoon bridge.

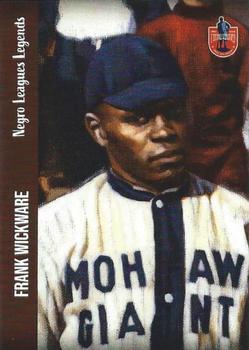

Unable to obtain the rights to a White semipro team, Wernecke decided to bring in outside professional Black players. Following the common practice at the time of raiding other teams’ players, he hired William “Big Bill” Smith, a Black baseball player, to find and lure players by offering nonseasonal full-time jobs.2 While many Black players came to Schenectady for short stays, the Mohawk Giants’ lineup included at times such prominent players as Smokey Joe Williams, Chappie Johnson, Harry Buckner, Grant “Home Run” Johnson, and Frank Wickware.3

Drawing on Smith’s exceptional recruiting talents, the 1913 Mohawk Giants were an outstanding team. Against regional White semipro teams, other Black professional teams, and White minor-league teams, their documented aggregate record was 52 wins, 22 losses, and 2 ties for a winning percentage of .703.4 They tied their series against Nat Strong’s Brooklyn Royal Giants, and defeated the Philadelphia Giants, the Cuban Giants, and the Norfolk and Atlanta Dixie Giants. In their 12 games against White minor-league teams, the Mohawk Giants won 9, lost 2, and tied 1.5

If Rube Foster’s quote is meaningful—“the main strength of all baseball nines lies in their pitchers”—then the success of the Mohawk Giants resided within Wickware’s gifted arm.6 In 1913 the 25-year-old right-hander’s documented pitching record was 24 wins, 5 losses and 2 ties.

With victories came attendance, and with fan support came profits. Wernecke’s risk was paying off and by midseason he expanded the seating at Island Park from 2,000 to 2,800.7 Like many Black baseball teams, independent and Negro Leagues alike, there was significant movement of players in and out of the Mohawk Giants lineup. In the second half of the season, team composition stabilized as stars Wickware and 40-year-old right fielder Buckner, whose career in elite Black baseball dated to the 1896 London Creole Giants (based in Muncie, Indiana), remained regulars.

The highlight of their successful season did not occur until the last game of the year, when it was announced that Walter Johnson and a team of mostly minor-league players would play the Mohawk Giants on October 5. Johnson had completed an incredible year with the Washington Senators at age 25, winning the Chalmers Award as the American League’s Most Valuable Player, while compiling a 36-7 won-lost record with an earned-run average of 1.14.8

The excitement accompanying Johnson’s appearance in Schenectady brought an estimated 8,000 spectators to Island Park.9 The overflow crowd encircled the outfield and effectively formed a human outfield fence.

As the umpire signaled to begin the game, all but three of the Mohawk Giants ran off the field, crossed the pontoon bridge and loudly assembled at the ticket booth entrance. A boycott led by Wickware was underway. Wernecke owed them $921.10 A chaotic and dangerous situation arose as fans and opposing players recrossed the pontoon bridge to better understand the delay.

The Schenectady police sent silent owner Alfred Nicolaus to Wernecke’s office for appropriate player remuneration. He returned with $500. The money was to be disbursed to all the Mohawk Giants. By the time the appeased team returned to the ball field, approximately 75 minutes of playing time had been lost.

Two pitches into the game, the general manager of the Walter Johnson All-Stars, Dave Driscoll, interrupted the game to demand immediate payment of their portion of the gate receipts. The police immediately ordered Driscoll to sit down and threatened to distribute the All-Star earnings to the frustrated fans.11

When the game finally resumed, the fans were treated to a great pitching duel between Johnson and Wickware. In October’s reduced light, with a late start, the game was shortened to 5½ innings.

Johnson was brilliant, striking out 11 batters and giving up only two hits. In the fourth inning, Mohawk Giants catcher-manager Phil Bradley hit a routine fly ball into left field that landed in the overflow crowd. It was ruled a ground-rule double. A subsequent stolen base and outfield fly produced the game’s only run.

Wickware’s performance was not as sharp as Johnson’s, but he scattered five hits on his way to a shutout. Two of the hits were doubles by Johnson himself.12 Fans walked away satisfied that they had seen the world’s best pitcher and relished the success of their home team’s 1-0 victory over the barnstorming All-Stars.

While national and local press coverage of Johnson and Wickware’s exploits were extensive, few newspapers captured the game’s intriguing backstory as well as the New York Times’s article “Walter Johnson Loses: Senators’ Pitcher Drops Game to Colored Team After Near Riot.”13

The great 1913 season for the Schenectady Mohawk Giants team had come to an end. For the next two weeks, the highly sought-after Wickware continued to pitch for teams in the New York City area. That summer Wernecke had made a lot of money, and he left his family and moved to South America, where he worked as a construction engineer for the rest of his life.14

The Schenectady Mohawk Giants returned to play in 1914 under new ownership and management, but their 1913 success was not to be repeated. The future of Negro League Baseball in Schenectady, however, would once again be thrilling, as a great Schenectady Mohawk Giants team resurfaced in the 1920s and 1930s.

Wickware’s career in Black professional baseball was long and storied. Originally hired by Rube Foster for the Chicago Leland Giants in 1910, he greatly benefited from Foster’s tutelage. From 1910 until 1920, his blazing fastball and pinpoint control made him a premier pitcher in the Negro Leagues. He was considered in 2006 for election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Special Committee of the Negro Leagues.15 He returned to Schenectady to live and died in 1967 at age 79. He is buried at Vale Cemetery in Schenectady, New York.

Author’s note

Thomas Disher and Marianne Rae provided motivation and research assistance. I would like to thank the staff of the Schenectady (New York) Historical Society for allowing me to peruse the Frank M. Keetz Collection highlighting the history of baseball in Schenectady. Additionally, longtime SABR member Frank Keetz’s self-published book, The Mohawk Colored Giants of Schenectady, is a detailed (but nonannotated) account of an independent Negro League team’s history in a predominantly White community. The character and strength of the Keetz book is its ability to inform the reader of the complexity, challenge, and beauty of the struggle of Negro League players to overcome the barriers of discrimination to bring high quality and exciting baseball to an upstate New York small industrial city. Finally, through membership in the New York Public Library, I was able to access historical newspapers using the ProQuest Database.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Seamheads.org for pertinent information.

Notes

1 Frank M. Keetz, The Mohawk Colored Giants of Schenectady (Schenectady, New York: Self Published, 1999), 5-6.

2 Keetz, 6-7.

3 Keetz, 7.

4 Keetz, 7.

5 Keetz, 7.

6 Mark Ribowski, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues from 1884 to 1955, (New York: Citadel Press, 1995), 61.

7 Keetz, 8.

8 Keetz, 14. A day earlier, on October 4, the Senators had beaten the Boston Red Sox 10-9 in the final game of the 1913 regular season. In a game with many odd or farcical moments, Johnson started in center field, then took the mound for two batters in the ninth inning before returning to center for the end of the game.

9 Ryan Mahoney, “Schenectady Baseball History: The Mohawk Giants,” New York Almanack, March 6, 2013. https://www.newyorkalmanack.com.

10 Keetz, 15.

11 Keetz, 15.

12 Keetz, 16.

13 “Walter Johnson Loses: Senators’ Pitcher Drops Game to Colored Team After Near Riot,” New York Times, October 6, 1913: 8.

14 Keetz, 16.

15 Keetz, 17; Stephen V. Rice, “Frank Wickware,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, accessed April 28, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/frank-wickware/.

Additional Stats

Schenectady Colored Mohawk Giants 1

Walter Johnson All-Americans 0

Island Park

Schenectady, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.