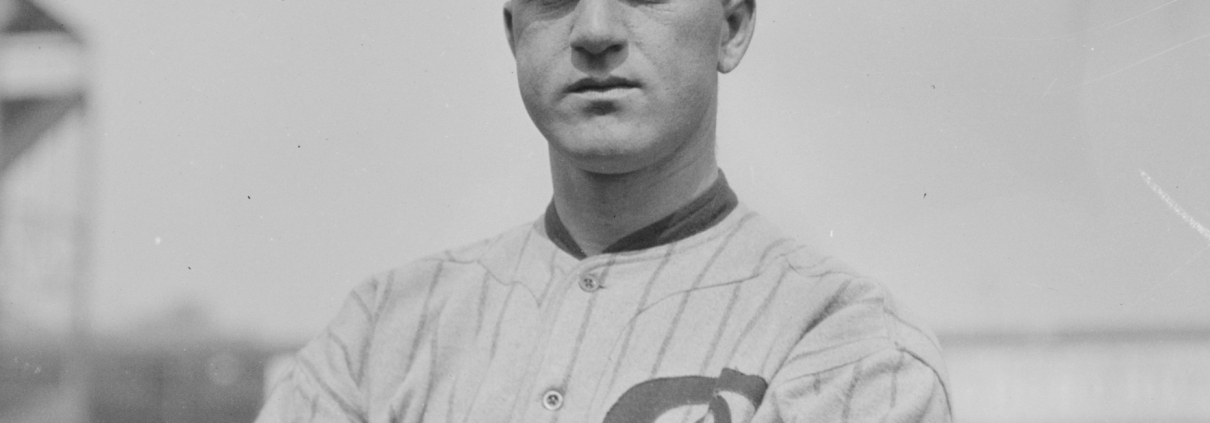

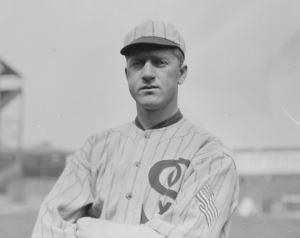

October 7, 1917: Red Faber’s pitching, not baserunning, lead to White Sox victory in Game 2

Before his first career World Series start, Red Faber was mostly known for the way he got his job in the big leagues: by impressing John McGraw on the world tour organized by the New York Giants manager and Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey back in 1913.

Before his first career World Series start, Red Faber was mostly known for the way he got his job in the big leagues: by impressing John McGraw on the world tour organized by the New York Giants manager and Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey back in 1913.

Faber was an unproven minor leaguer then, but Comiskey took the pitching prospect along for the ride as an extra arm in case one of his stars got hurt on the four-month adventure around the globe.1 McGraw took a liking to the White Sox recruit and helped him work on his spitball, which Faber used to earn a spot on Chicago’s major-league roster the following spring.

In 1917 Faber got his chance to show McGraw just how much he had learned. No White Sox player would play a more important role in the fall classic against New York’s National League champions.

Back in the World Series for the first time in 11 years, the White Sox had won 100 games in the regular season largely on the strength of their deep pitching staff, which posted a major-league-leading 2.16 ERA. Ace Eddie Cicotte held the visiting Giants to seven hits to win the World Series opener, 2-1, and now it was Faber’s turn to stop an explosive offense that had led the NL in runs scored, home runs, and stolen bases.

The 29-year-old right-hander from Cascade, Iowa, was in his fourth big-league season but he had yet to make much of a name for himself. His career-best 1.92 ERA was marred by an inconsistent 16-13 record and he was used by manager Pants Rowland nearly as much out of the bullpen as in the starting rotation until the season’s final weeks.

In Game Two against the Giants in front of about 32,000 fans at Comiskey Park, Faber became almost as much of a World Series goat as a hero.

New York opened the scoring in the second inning on a two-run single by Lew McCarty to score Dave Robertson and Walter Holke. When Robertson kicked away left fielder Joe Jackson‘s throw home, which was scored as an error on catcher Ray Schalk, Holke came scampering home for a second run. “Things became so quiet in the grandstand that one could hear the sparrows chirping in the rafters,” the Chicago Tribune reported.2

But the White Sox quickly returned serve against Giants starter Ferdie Schupp with two runs of their own in the bottom half of the inning, thanks to consecutive hits by Jackson, Happy Felsch, Chick Gandil, and Buck Weaver, all singles. After Schupp walked the light-hitting Faber, McGraw had seen enough. He lifted his starter after just 1⅓ innings. His strategy of using southpaws like Schupp, Rube Benton, and Game One starter Slim Sallee against the White Sox offense, led by the left-handed-hitting Jackson and Eddie Collins, was quickly backfiring.

After relieving Schupp, right-handed spitballer Fred Anderson deftly escaped a bases-loaded jam by striking out Nemo Leibold and inducing Fred McMullin to ground out. But he could hold off the White Sox onslaught for just one more inning. In the fourth, the home team’s bats came alive to break the game open.

Weaver led off with a bunt single and moved up on Schalk’s single. After Faber popped out, Leibold singled in Weaver with the go-ahead run and McMullin doubled the White Sox’ lead with another base hit. That ended Anderson’s day and another right-hander, Pol Perritt, came in to limit the damage. Collins greeted him with an RBI single and Jackson added another to make the score 7-2. Felsch mercifully ended the Giants’ misery with a line drive to second baseman Buck Herzog, who turned an unassisted double play.

The collapse of the Giants’ pitching “was one of the most pitiful incidents imaginable,” wrote Grantland Rice.3 “The Giants were supposed to have a fairly well-rounded staff, while the White Sox were supposed to be entirely dependent on Eddie Cicotte. … It was one of those occasions when one side does all the fighting and the other side is only beaten.”

Rice credited manager Rowland with calling for successful hit-and-run plays — one of McGraw’s signature strategies — on five of the White Sox’ seven run-scoring hits. “This stealing of their stuff has pained the Giants not a little,” he wrote.4

With Faber masterfully shutting down the Giants — only one New York baserunner got as far as second base in the final seven innings — the outcome was no longer in doubt. That set the stage for a little bit of levity and an all-time World Series blunder.

After reaching base in his first plate appearance, a rare occurrence for someone with only four hits in the regular season, Faber received an ovation from the Chicago fans when he stepped to the plate for his third plate appearance in the fifth. With two outs and Buck Weaver on second base, Faber promptly earned another round of applause by knocking a single to deep right field. Weaver must have been too surprised to get a good jump and only advanced to third base. Meanwhile, Faber moved up to second on the throw home.

On the next pitch, Faber surprised everyone in the ballpark by taking off for third base “without rhyme or reason or warning.”5 Weaver, taking a big lead, slid back into the bag at the same time as Faber arrived. Catcher Bill Rariden had the presence of mind to throw the ball to third baseman Heinie Zimmerman, who placed a tag on both runners in the dirt. Faber’s out was recorded to end the inning.

The play led to an oft-repeated, possibly apocryphal quote that still makes the rounds in baseball history books. When Faber reached third base only to find his teammate already there, a bewildered Weaver asked him, “Where in hell do you think you’re going?” Red looked up and supposedly replied: “Back to pitch.”6

White Sox beat writer I.E. Sanborn predicted that Faber’s blunder would be “dug up by the historians as the feature of the 1917 world’s series … a thousand, thousand years from now.”7 But by the end of the Series, it wasn’t even the most notable mistake on the basepaths that week, having been overshadowed by Zimmerman’s ill-fated footrace with Eddie Collins in Game Six.

Faber’s adventures at the plate and on the bases provided some amusement, but the Giants were stifled by his steady work on the mound. He threw an efficient 99 pitches, 63 for strikes, according to an analysis by the Chicago Tribune.8 The Giants swung early and often, allowing the White Sox pitcher to get out of the sixth inning on just six pitches. The ninth inning lasted only eight pitches.

In a game that epitomized the small-ball nature of the Deadball Era, the teams set a World Series record that still stands by combining for 22 singles and no extra-base hits.9

The White Sox were brimming with confidence heading to New York, having thrashed the National League champions two days in a row. “They knocked us silly,” one Giants player said.10 In a syndicated column written under Collins’s name, the Chicago team captain said, “The game showed we are capable of hitting all kinds of pitching: southpaws, spitters, fast and curveballs. I cannot see how they ever expect to stop us now.”11

Sources

Box scores for this game can be found at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA191710070.shtml.

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1917/B10070CHA1917.htm.

Notes

1 Brian Cooper, “Red Faber,” SABR BioProject, accessed online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/a6dff769 on January 16, 2018.

2 James Crusinberry, “It’s All Over but Shouting, Fans Believe,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1917: 13.

3 Grantland Rice, “Teams Hurrying Eastward With Sox Two Games Ahead,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 8, 1917: 20.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 For two of many examples over the years, see Irving Vaughan, “Faber Attributes Long Diamond Life to Spitter,” Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Argus-Leader, February 17, 1929: 8; and Daniel Okrent and Steve Wulf, Baseball Anecdotes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 73-74.

7 I.E. Sanborn, “White Sox Whale Giants, 7-2,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1917: 1.

8 “Red Faber Pitches 99 Balls at Giants,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1917: 13.

9 In 1971, the Baltimore Orioles tied the White Sox’ team record with 14 singles and no extra-base hits in Game Two against the Pittsburgh Pirates. But no World Series game has come close to the 22 combined singles that the White Sox and Giants had in 1917. See: https://baseball-reference.com/tiny/Qx0kA.

10 Damon Runyon, “Defeat Dazes McGraws,” Chicago Examiner, October 8, 1917: 9.

11 Eddie Collins, “Sox Have the Punch — Collins,” Chicago Examiner, October 8, 1917: 8.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 7

New York Giants 2

Game 2, WS

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.