September 1, 1897: Bob Allen has big day for Beaneaters — as Bostonians begin to travel underground

Baseball wasn’t the only thing on the minds of Bostonians on September 1, 1897. That was the day that the first subway system in the United States began operations.

Motorman James Reed drove the first car, bearing about 150 people and departing Park Street station at 6:02 A.M. Conductor Gilman Trufent collected the 5-cent fares.

Before the day was over, tens of thousands of people had paid their fares and tried out the new subway; the Boston Globe pegged the figure at “between 200,000 and 250,000.”1 The Boston Daily Advertiser calculated 75,000.2 Aboveground, grievously overcrowded Tremont Street was now passable again with so many of the streetcars traveling unimpeded underground.

But there was also a very big game scheduled for the Boston Ball Grounds at 3:30 that afternoon. One could take in both events. The local nine, dubbed the Beaneaters by many, had won three pennants in a row from 1891-93, but had now fallen short three years and finished fourth in 1896. Yet as August closed, they were tied with the Baltimore Orioles – in fact, a little behind in percentage points. Baltimore was 72-32 (.692) and the Bostons were 74-34 (.685). On August 31 Boston had hosted the Chicago Colts, the game ending in an 8-8 tie.

Boston had been behind from the start of the season through June 19, reaching first place for a day on June 21. They dropped back a game on the 22nd, but on the 23rd they pulled ahead in the standings for good. They held that lead until the game on August 31, when they dropped into a tie. There were 24 games left on the schedule. Every one of them was going to count.

The Colts were 24 games behind the leaders, ensconced in sixth place in the 12-team National League. They were led by Cap Anson, who managed and played first base. Captaining the Boston team was Hugh Duffy. The Colts and Beaneaters had gone at it earlier in the season, Boston winning five of their first six meetings, but then dropping all three games in Chicago in early July. With the tie game on August 31, Boston was 5-4-1.

Starting for Boston was pitcher Ted Lewis. He’d been 1-4 in his first season, 1896, but the right-hander was on his way to a 21-12 season in 1897. Chicago countered with Danny Friend, a lefty the same age as Lewis (24). Friend was in his second full season; he had been 18-14 (4.74) in 1896, and would finish 1897 at 12-11.

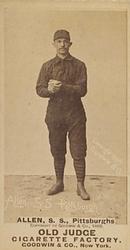

Former bank clerk Bob Allen was arguably the star of the day. He had turned 30 in July and after five years with the Phillies was out of baseball in 1895 and 1896. He played shortstop in 32 games for Boston in 1897, including the September 1 game. Regular shortstop Herman Long was “on the hospital list.”3 Allen was asked to bat seventh in the order.

Boston won the game, but the Globe overlooked Allen in its lead, concluding, “[T]o Capt. Duffy belongs the credit of saving the game for Boston.”4 In a subhead, the paper acknowledged that Allen’s batting was “the feature of the game.”

Neither team scored in the first inning, first baseman Anson making all three putouts for the Colts. In the second, Jimmy Callahan tripled for Chicago, over Duffy’s head in left field, but was left stranded. Duffy drew a walk in the bottom of the second, took second base on a groundout by Jimmy Collins, and then scored when Allen singled. Chicago tied it up with a one-out double by pitcher Friend followed by shortstop Bill Dahlen’s single.

Chick Stahl singled to lead off Boston’s the fourth, but was forced at second by Duffy’s bunt hit a little too hard. Collins doubled to right field, putting men on second and third. Allen then singled between third and short, driving in both baserunners. Fred Lake flied out to short, Lewis singled, and Billy Hamilton drew a walk. The bases were loaded and Fred Tenney got a “scratch infield single”5 which scored Allen. Bobby Lowe grounded out to the end the inning, but it was 4-1 Boston.

And Boston added two more in the fifth. In the top of the inning, Chicago got two men on base but Lewis worked his way out of the jam. In the bottom of the inning, Collins drew a walk and then trotted home when Allen hit a home run over the fence in left field. Boston got a couple more men on base (Lake and Lewis both singled), but no more scored.

Lewis walked the first batter in the top of the sixth, then Callahan singled, and catcher Malachi Kittridge drew a one-out walk to load the bases. Friend flied out to the catcher. Lewis might have gotten out of the inning, but third baseman Bill Everitt singled past second base to drive in two. It was now 6-3, still in Boston’s favor.

When center fielder Bill Lange singled to start off the seventh and Anson “dropped a lucky one into left field,”6 Hugh Duffy made a move, calling in Kid Nichols to relieve Ted Lewis. Lange scored on an out, but only the one run came home. It was 6-4. The move to replace Lewis was unpopular with some fans, who hissed when Duffy came up to bat. The Boston Journal wrote that “several hundred began to hiss like silly geese.”7 But, wrote the Globe’s Tim Murnane, “Four-fifths of the spectators applauded the little captain who had the brains and the nerve to take a chance and save the day.” After all, Murnane continued, “The time to change the pitcher is before the game is lost.”8

Why this hissing? The Journal said it was the “shoestring gamblers” who reacted for “the most mercenary of motives, they had placed their paltry dollars on Chicago, and they feared that Duffy had played a card which would deprive them of possible small winnings.”9

The Journal observed that three times Lewis skirted bigger problems, and – while he might have escaped the seventh, too, had Lowe executed a possible double play, what it called his “record of unsteadiness holds.”10 Three times he’d loaded the bases, but escaped more serious damage, noted the Chicago Tribune, crediting the timing of Boston’s batters: “it was opportune hits that piled up the runs for Boston.”11 Umpire Lynch, the Tribune wrote, made a couple of controversial calls, both going against the Colts.

Nichols helped give his team an insurance run in the eighth, hitting a ball off the top of the left-field fence for a double. With two outs, Tenney hit a short one that dropped into center despite Lange’s valiant effort at a catch. Nichols scored.

After Lange reached on a slow roller to third base in the top of the ninth, Nichols retired the next three batters, though Jimmy Ryan sent one deep to the flagpole in center before Hamilton snared it. The game ended with a 7-4 win, in 2:03 before 4,150.

In the second inning, Bob Allen had singled in Duffy. In the fourth inning, he singled in both Duffy and Collins. And in the fifth inning, he hit the two-run homer. He was credited with 34 RBIs in 1897, but five of them were from this one game.

The Boston Journal featured Allen’s accomplishments under the headline “Bob Allen’s Day,” noting his fielding as well as his batting, doing more than might be expected of a utilityman.12

Murnane rightly concluded, “The absorbing topics of the day were the opening of the subway and Bob Allen’s batting.”13

Notes

1 “Every Car Crowded,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1897: 1.

2 “Big Crowds Thronged the Newly Opened Subway,” Boston Daily Advertiser, September 2, 1897: 1.

3 “Allen’s Hitting,” Boston Daily Advertiser, September 2, 1897: 8.

4 T.H. Murnane, “No Change for Better,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1897: 5.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 “Bob Allen’s Day,” Boston Journal, September 2, 1897: 1.

8 T.H. Murnane.

9 “Bob Allen’s Day.”

10 Ibid.

11 “Hit at Proper Time,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1897: 4.

12 Ibid.

13 T.H. Murnane.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 7

Chicago Colts 4

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.