September 10, 1881: Roger Connor’s ‘ultimate’ grand slam

Nearly half a century before baseball borrowed the expression “grand slam” from contract bridge,1 and more than a century before someone first referred to a “walk-off” home run2, Roger Connor accomplished both with a single swing of his bat.

Troy, New York, and Worcester, Massachusetts, were at the time members of the National League, the former for four seasons, 1879–82, and the latter from 1880–82. Neither was a serious contender but both were competitive. Both had their best finishes in 1880, with Troy finishing fourth, a game ahead of Worcester. Troy would finish fifth in 1881 just two games out of the first division, while the Worcesters finished last in the eight-team circuit. Worcester’s demise was due for the most part to manager Frank Bancroft’s departure for Detroit accompanied by key players Art Whitney, Charlie Bennett, Lon Knight, and George Wood.

The two teams met for the 12th and final time of the 1881 season on September 10 in a game that meant little for either. By virtue of sweeping the first five games of the year, Worcester led in the season series eight games to three. Rather than being played at Troy as scheduled, due to a rainstorm that made their regular field unplayable, the contest was staged at Riverside Park on privately owned Bonacker Island in East Albany (now Rensselaer.)3

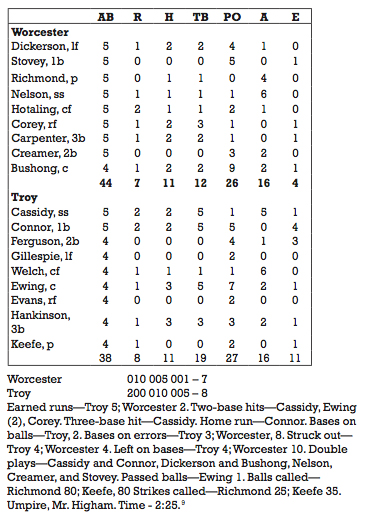

Until the day’s final swing, the game itself was unremarkable. The Worcesters held a 7–3 lead going to the bottom of the ninth.4 The New York Clipper described what the Troy lineup then did against lefthander Lee Richmond: “The Troys went to the bat in the last half of the ninth inning, wanting four runs in order to tie their opponents’ score. Mickey Welch, Buck Ewing and Frank Hankinson filled the bases on safe hits, Jake Evans was retired, Tim Keefe was given his base on balls, sending in Welch. John Cassidy was the second man out, and then Connor cleared the bases and made a clean home run, thus winning …”5 The Worcester Daily Spy described Connor’s hit as “a terrific drive to right.”6 Connor’s two-out blow gave his team a stunning 8–7 win.

The account of the game from the Troy Daily Times is not complimentary of the day’s play and curiously describes Connor’s hit only in closing:

Troy’s Last Game with Worcester Won By a “Scratch.”

The Albany Argus says that the 100 persons who attended Saturday’s Troy-Worcester game at Riverside [P]ark saw the most “barbarous base ball” and “funny fumbling” ever seen on the diamond. The errors of the Troys, it says, were more numerous than their hits, and the play was only notable for its lack of life. The [R]uby [L]egs scored five runs in the sixth chiefly on errors, and the Trojans in the last innings made five runs by the “funny fumbling” of Hick Carpenter, the poor pitching of Richmond and the accidental hit of the Megatherian Connor.

There would not be another walk-off grand slam in a three-run game until Babe Ruth duplicated the feat on September 24, 1925.7

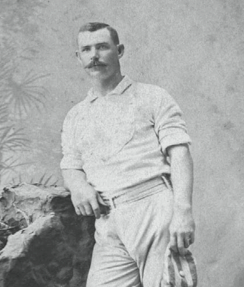

That Connor would be the first to have such a memorable power-hitting feat seems fitting. He was a robust, 6-foot-3-inch left-handed hitter. And though this home run, only his fifth, came in just his second season in the major leagues, he went on to hit many more. His lifetime total of 138 stood as the career best until it was topped by Babe Ruth in 1921. Though Connor led his league in home runs in only one season, he hit 10 or more seven times for another 19th-century record, and once hit three home runs in a game.8

Connor’s solid career landed him in the Hall of Fame. Three other members of the 1881 Troys, all also in their second major-league season, have also been enshrined: Mickey Welch, Buck Ewing, and Tim Keefe.

The major leagues’ second grand slam was hit just 19 days later. Harry Stovey of the same Worcester club connected on the season’s next-to-last day, September 29, against pennant-winning Chicago. Oddly, the pitcher of the first grand-slam ball, Lee Richmond, was on the bases for Worcester at the time.9

Notes

1 Dickson, Paul. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. (New York: W.W. Norton Company, Inc., 2009), p. 381, dating the term’s baseball application to 1929.

2 Dickson, op. cit., p. 909, dating the term to 1988.

3 New research by historian Matt Malette has shown that the long-reported location of this game at Riverside Park in Albany was incorrect. “Someone got it wrong 138 years ago by labeling the grand slam in Albany instead of East Albany,” Malette told the Albany Times-Union in 2019. For more information, see Paul Grondahl, “Baseball’s official historian settles grand slam debate,” Albany Times-Union, April 24, 2019, https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Grondahl-Major-League-Baseball-s-official-13788678.php.

4 Worcester Daily Spy, September 10, 1881.

5 New York Clipper, September 17, 1881, p. 413.

6 Worcester Daily Spy, September 12, 1881.

7 “Collecting Home Runs-Ultimate Grand Slams,” Baseball Quarterly Reviews (Schenectady, New York, 1991)

8 https://www.baseballhall.org/hof/connor-roger.

9 Bob McConnell, letter to John R. Husman referencing the Tattersall Home Run Log, December 10, 1984.

Additional Stats

Troy Trojans 8

Worcester Brown Stockings 7

Riverside Park

Rensselaer, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.