September 10, 1933: The Game of Games: Negro Leagues stage first all-star game at Comiskey Park

“The East-West Game became the spirit and life of Negro League baseball, serving to entertain, educate, and ultimately provide a forum to integrate our national pastime many years later.” — Larry Lester1

The idea for a Negro League all-star game is attributed to sportswriters Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier in July of 1933. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, suggested that the writers contact Robert Cole, owner of the Chicago American Giants, and look into holding an East-West game at Comiskey Park in Chicago. The deal was made with Cole, the park was secured for a September 10 date, and publicity began in earnest. The game would annually prove to be “the pinnacle of any Negro League season,” wrote Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester. “It was an all-star game and a World Series all wrapped in one spectacle.”2

The idea for a Negro League all-star game is attributed to sportswriters Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier in July of 1933. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, suggested that the writers contact Robert Cole, owner of the Chicago American Giants, and look into holding an East-West game at Comiskey Park in Chicago. The deal was made with Cole, the park was secured for a September 10 date, and publicity began in earnest. The game would annually prove to be “the pinnacle of any Negro League season,” wrote Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester. “It was an all-star game and a World Series all wrapped in one spectacle.”2

Fans could vote for their favorite players through African-American newspapers including the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Kansas City Call, and Baltimore Afro-American. The significance was monumental, as Negro League legend Buck O’Neil remembered. “While the big leaguers left the choice of players up to the sportswriters, Gus (Greenlee) left it up to the fans. After reading about great players in the Defender and Courier for so many years, they could cut out that ballot in the black papers, send it in, and have a say. That was a pretty important thing for black people to do in those days, to be able to vote, even if it was just for ballplayers, and they sent in thousands and thousands of ballots.”3

With just over a million votes cast, Oscar Charleston of the Pittsburgh Crawfords received the most votes, 43,793, while Willie Foster of the Chicago American Giants was runner-up with 40,637. Each was joined by six teammates in the starting lineups.4 The crowd of 19,568 braved the drizzly weather, many arriving on packed train cars. The Illinois Central Railroad needed a special coach to bring fans in from New Orleans, while others arrived by rail from Mississippi and Tennessee. The Sante Fe Chief brought fans from Kansas City and Wichita, while the New York Central brought fans from the East.5 “The depression didn’t stop ’em — the rain couldn’t —and so a howling, thundering mob of 20,000 souls braved an early downpour and a threatening storm to see the pick of the East’s baseball players battle the pick of the West,” wrote Al Monroe in the Chicago Defender.6 With such high stakes, the Kansas City Call thought Greenlee must have “lost 10 pounds worrying over the possibility that rain might ruin the game.”7

Around 2:30 P.M. the umpires, Costello, Cusack, Baldwin, and Stack, “moved from beneath the home dugout like groundhogs searching for that proverbial shadow, only braving steady drizzle to yell the usual ‘Play ball!’” West was the home team, and Foster stood on the mound in the drizzle staring in at Cool Papa Bell. The “Game of Games” was on.

Bell flied out to left, and both clubs went quietly in the first two innings, with Sam Streeter of Pittsburgh on the hill for the East. Jud Wilson’s single in the second for the East was the first hit in the history of the East-West game. In the bottom of the third, Sam Bankhead of Nashville beat out an infield hit, the West’s first hit of the game. Moving to second on a groundout, Bankhead scored the first run in the game’s history, on a single by Chicago’s Turkey Stearnes.

Trailing 1-0 in the top of the fourth, the East got its first two men aboard when Rap Dixon of the Philadelphia Stars walked and Charleston was hit by a pitch. They performed a double steal while Biz Mackey of Philadelphia struck out. Wilson, also of Philadelphia, grounded to second. Leroy Morney of the Cleveland Giants threw wildly to the plate and both Dixon and Charleston scored, with Wilson taking second. Dick Lundy of Philadelphia walked and Vic Harris of the Homestead Grays grounded to Morney, who booted an easy double-play opportunity. The bases were loaded. John Henry Russell laid down a perfect suicide-squeeze bunt along the first-base line, scoring Wilson. The East now led, 3-1.

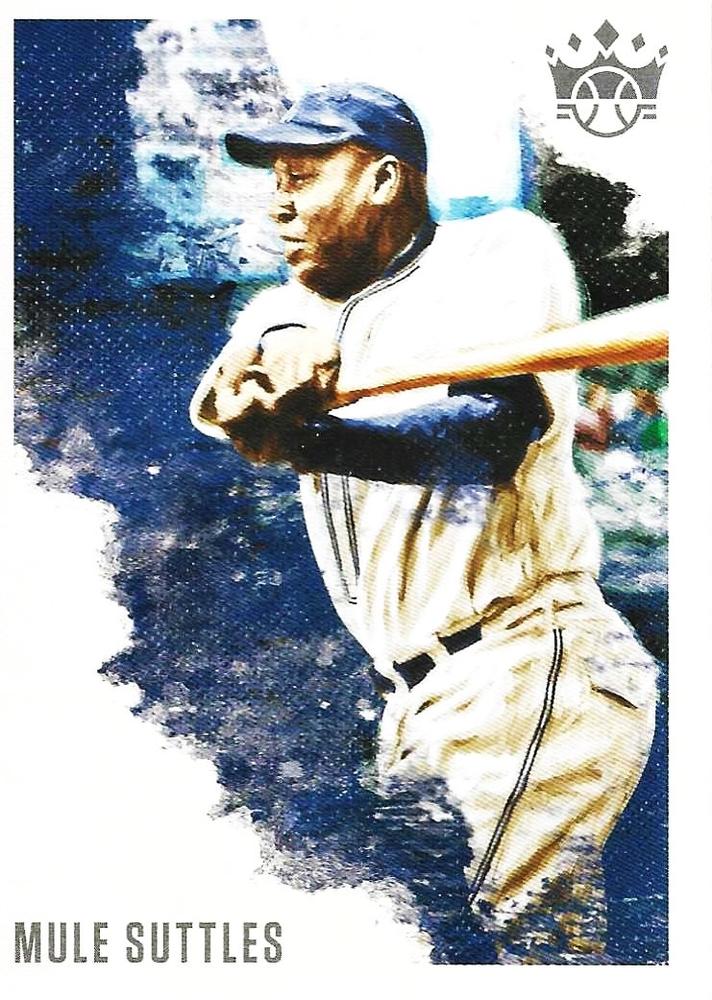

The lead changed quickly in the bottom of the inning. Chicago’s Willie Wells doubled and scored on teammate Steel Arm Davis’s double to cut the East’s lead to 3-2. Chicago’s Mule Suttles received a strong ovation from the crowd “because Mule, to colored fandom,” wrote William Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier, “is what Ruth is to major-league baseball.”8 Suttles smashed a home run into the upper deck in left-center to give the West a 4-3 lead. “With hardly any effort he swung,” Nunn wrote. “Like a bullet from a rifle. ‘Cool Papa’ Bell started to run. Suddenly he stopped. Pandemonium reigned. Straw hats filled the air … worth the price of admission any day.”9 The first home run in the East-West game was indeed a memorable one. Naturally, it was Ruth who hit the first home run in the major-league All-Star Game two months earlier, in the same park.

The East countered with two runs in the top of the fifth when Dixon reached on a checked-swing roller in front of the plate. Charleston was again hit by a pitch and Mackey blooped a single to load the bases with one out. Wilson singled to left, scoring Dixon and Charleston to give the East a 5-4 lead. Lundy hit a fly ball to right that scored Mackey, but an appeal play resulted in Mackey being called out for leaving third too soon. In the bottom of the fifth, Larry Brown of Chicago tripled to center but was tagged out when he overran third base.

The West struck again in the bottom of the sixth. Wells singled and scored on a double by Alex Radcliffe of Chicago to tie the score, 5-5. As the rain came down, Bertram Hunter of Pittsburgh came in from the bullpen to pitch for the East. Suttles was clutch again, doubling to right, scoring Radcliffe, and then he too scored on single by Morney. Brown singled to right but Morney was out on an appeal play when he failed to touch second base on the way by. Despite the blunder, the West now led, 7-5.

Josh Gibson was now catching for the East in the bottom of the seventh. A leadoff single by Foster, the first such by a pitcher in the game’s history, led to a pitching change; George Britt of the Homestead Grays came in to pitch. Stearnes doubled to right, sending Foster to third. A fly ball by Wells scored Foster. Davis doubled to right, scoring Stearnes. Radcliffe’s single and a misplay by Harris in left field scored Davis. The West led, 10-5.

In the top of the eighth the East put the first two runners on when Gibson and pinch-hitter Judy Johnson singled, but both were stranded when Foster got Lundy to line out, Fats Jenkins to ground out, and Russell to pop out. The West added a run in the bottom of the eighth. The East scored two in the top of the ninth on flies by Dixon and Charleston, but Gibson lined out to Davis in left for the final out of the West’s 11-7 victory.

Every player in the lineup for the West had at least one hit, with six players having two each of the 15 total. Foster pitched the entire game, allowing the East only seven hits and three earned runs. While Nunn called it “a game which produced thrills galore,” one of the game’s greats didn’t show.10 Satchel Paige declined the invitation and remained in the hills of North Dakota, pitching for his integrated Bismarck semipro team.11

The only mention of the game in the Chicago Tribune was a two-paragraph item under a Dick Tracy comic strip.12 The Sporting News, the self-proclaimed “Baseball Paper of the World,” didn’t mention the “Game of Games.” Undeniable, however, was the conversation around baseball that resulted from it.

Henry L. Ferrell of the Chicago Daily News quipped that Charleston, Suttles, and Lundy would each get a major-league contract if the they “were of a lighter shade.”13 Ferrell also believed some cities wanted to see a winner, no matter the color of their skin. The East team, he said, “might well be moved as a unit into Cincinnati or Boston, where the long suffering patrons of the Reds and the Red Sox have been praying for a magic rod to strike a rock and appease their thirst for a team.”

The Chicago Defender wrote in its September 16 issue, “If the white club owners of the National and American leagues would surrender their prejudices and recognize fitness and ability instead of color, baseball would be established firmly on the grounds of clean and wholesome sport.” The East-West game reportedly outdrew the crowd across town watching the Cubs play a doubleheader at Wrigley Field.14 “Professional baseball has been and is losing thousands of dollars yearly by its narrow and asinine prejudiced attitude in the operation of the national game,” the Defender wrote. “We ask again: What is the matter with baseball? The answer is, plain prejudice — that’s all.”

It would be several years before baseball dealt with its “prejudiced attitude,” but the “Game of Games” was an early sign of better days ahead.

Sources

Dickson, Paul. “The Negro Leagues East-West All-Star Game,” The National Pastime Museum. March 12, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017. https://thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/negro-leagues-east-west-all-star-game.

Photo credit: Mule Suttles, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 25.

2 Lester, 1.

3 Lester, 3.

4 Lester, 37. The rest of the top 10 in voting: Turkey Stearnes 39,994; Willie Wells 39,136; Newt Allen 39,092; Jud Wilson 37,681; Alec Radcliffe 36,712; Josh Gibson 35,376; Mule Suttles 35,134; John Henry Russell 29,846.

5 Lester, 3.

6 Al Monroe, “20,000 See West Beat East in Baseball ‘Game of Games,’” Chicago Defender, September 16, 1933. Reprinted in Lester, 30-31.

7 “Heavy Hitting Beats East in Classic,” Kansas City Call, September 15, 1933. Reprinted in Lester, 30.

8 William G. Nunn, “West’s Satellites Eclipse Stars of the East in Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 16, 1933. Reprinted in Lester, 32.

9 Ibid.

10 Nunn.

11 “Satchel Paige and Barney Brown are Expected to Pitch,” Bismarck Tribune, September 9, 1933: 6; Lester, 42.

12 “West Victor, 11-7, in Negro All-Star Game,” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1933: 21.

13 “Charleston, Lundy, Suttles Ranked as ‘Major League Timber,’” Pittsburgh Courier, September 16, 1933: 5.

14 Attendance numbers are not available for that game.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.