September 10, 1934: Happy New Year, Hank Greenberg!

At the end of the day on September 8, 1934, the Detroit Tigers, who had not been to the World Series since 1909, stood 4½ games ahead of the powerful New York Yankees. This lead had been constricting around the neck of the Tigers since September 5, when the lead stood at 6 games.

At the end of the day on September 8, 1934, the Detroit Tigers, who had not been to the World Series since 1909, stood 4½ games ahead of the powerful New York Yankees. This lead had been constricting around the neck of the Tigers since September 5, when the lead stood at 6 games.

Fans of the team grew more nervous with each day — was the pressure of the pennant race starting to consume them? Prior to splitting a doubleheader with Connie Mack’s lowly Philadelphia Athletics on that day, the Tigers had won only two games in the early days of September. And now the Boston Red Sox, a middling .500 unit that season, were arriving in town for a four-game series. If they couldn’t do better than take two of five games from the A’s, how disastrous would an engagement with the Red Sox prove to be?

On Sunday, September 9, the Tigers tried to allay the fears of their hometown faithful with a victory in game one against the Sox, prevailing 5-4 in 10 innings. Despite the win, in which the Tigers coughed up the lead in the top of the ninth, then secured victory in the bottom of the 10th, the Yankees continued to make things interesting, taking a doubleheader from the St. Louis Browns. The Tigers’ lead shrank further, from 4½ games ahead to 4 games.

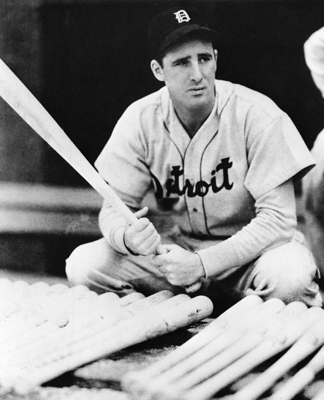

To make matters even more worrisome for Detroit rooters, Hank Greenberg, the Tigers’ young slugging sensation, and the hero of the day in the September 9 contest, was struggling with his own decision regarding his availability on the following day. September 10, 1934, was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year and the traditionally observed start of the High Holy Days of the Jewish calendar. Greenberg, who never viewed himself as particularly observant of Jewish rituals and traditions, nonetheless wanted to be respectful of his parents’ wishes. And yet he was also a key run producer in a lineup that had not been producing many runs of late.

Complicating matters further were the larger sociopolitical events of the day. In Europe, Adolf Hitler had risen to power in Germany, and was now well on the way to scapegoating Jews for the country’s ills and reducing their status in their native land to that of second-class citizens, a mere inkling of what was to come. Jews also were under attack in the United States, courtesy of Detroit’s own Henry Ford and Father Charles Coughlin. Through his own publications and through the influence that his wealth brought him, Ford time and again railed against Jews as the source of so many ills plaguing the United States before and during the Great Depression. Father Coughlin, the Catholic priest and radio show host, echoed these sentiments in his anti-Semitic broadcasts every week to millions of listeners.

There were, however, sympathetic and learned voices available to Greenberg, including local rabbis. When asked, they offered interpretations of Jewish law and custom for his consideration, taking into account Greenberg’s professional obligations to his teammates and fans, as well as to his faith. In the end, after arriving at Navin Field, and after talking with his manager, Mickey Cochrane, as well as several teammates, Greenberg reached into his locker for his uniform, dressed, and joined his team on the field.

Starting for the Red Sox on that Monday was Gordon Rhodes, a journeyman pitcher not known for his blazing heater; in 1934 he would average 3.2 strikeouts per nine innings, and would allow 247 hits and 98 walks, leading to a WHIP (walks plus hits per inning pitched) of 1.575. Surely the Tigers could make short work of Rhodes, despite their recent offensive struggles. Countering Rhodes would be Elden Auker, the young hurler for the Tigers enjoying something of a breakout season.

Auker immediately got into trouble against the Red Sox, as he gave up a walk to leadoff hitter Max Bishop, followed by a fielder’s choice to Billy Werber, which advanced Bishop to second base. Mel Almada, the rookie center fielder for the Red Sox, followed with an RBI bloop single to drive Bishop in from second. Auker then settled in and retired the next three Sox batters in order, but the early damage had been done. And with that began the fretting of the Tiger faithful.

The game remained 1-0 Red Sox into the bottom of the seventh inning, with only one Tiger advancing as far as second base between the second and seventh. Up first for the Tigers, shortstop Billy Rogell led off with another weak infield groundout. Next came Hank Greenberg. He had done the same in his first two at-bats as Rogell had just done, and opportunity to improve on that was getting to be in short supply.

Greenberg swung late at Rhodes’ first offering for strike one, but was able to work the count to two balls and two strikes. Then Rhodes went with a breaking ball, and Greenberg let the ball travel into his hitting zone. At the precise moment that a great hitter knows instinctively to let loose with a mighty cut, Greenberg did just that, launching Rhodes’ offering deep into left field. The Red Sox outfielders did not pursue the projectile, and the Tigers faithful, waiting nervously for something — anything — to cheer about, roared their approval as the ball sailed well over the scoreboard in left.

Marv Owen followed Greenberg’s home run with a single, and Gee Walker drew a pass from Rhodes. Red Sox skipper Bucky Harris panicked, sending the venerable Lefty Grove, this season a shadow of his former self with the Athletics, down to the bullpen to warm up. Rhodes recovered, sending Auker down on strikes and coercing a weak groundball out from White to retire the side. Nevertheless, Greenberg’s homer had done the job, and the score was now knotted at one run apiece.

Auker continued to contain the Red Sox hitters, putting them down in order in the top of the eighth inning. In the bottom of the inning, Cochrane once again reached base, preserving a perfect 2-for-2 day in four total plate appearances. Despite being on base for the fourth time in the game (single, double, walk, and hit-by-pitch), once again Black Mike could only watch as the heart of the order failed to deliver for the home team. Auker came back out in the top of the ninth, and dispatched the Red Sox hitters as efficiently as he had done from the second inning.

Now came the bottom of the ninth, and leading off — Hank Greenberg. As he climbed out of the dugout and stepped on to the field, he found himself in a position seemingly unexpected to him, given his struggles over whether to play on this day. Because of the decision to play, he now had the opportunity to provide a struggling team, and an anxious fan base, with a victory.

Rhodes, still in the game, started Greenberg off with a slow curve down in the zone. Greenberg let it go by, despite its being very similar to the pitch he had launched into the left-field bleachers in the seventh inning. Rhodes’ next offering was the last pitch thrown that day — Greenberg launched the ball into deep left-center. It was still rising in its flight as it sailed over the wall and beyond the confines of Navin Field. Much as the exterior confines of the ballpark could not contain Greenberg’s clout, the interior confines could not contain the frenetic masses of Tigers fans as he rounded the bases for home. Fans and photographers alike welcomed Greenberg at the plate, and his teammates showered him with appreciation in the clubhouse for his choice to play, and for his singular effort in the victorious outcome.

Hank had struck two blows in the game itself, one to tie the score, and one to win the game. He had also struck a larger blow for the Tigers’ pennant chances, which improved to a 4½-game lead over the Yankees, rained out that day in St. Louis. But perhaps the greatest blow that day was against the steady expression of anti-Semitism heard and read about in American daily life.In the backyard of that vitriol, Hank Greenberg, already one of the best known and most beloved of Jewish athletes, became one of the most beloved of Detroit baseball stars by both Jew and gentile alike. And while the Tigers’ lead in the American League vacillated over the next few weeks before the team clinched the pennant, the questions of whether the team would fold down the stretch, and whether Greenberg would be there to help see the team to that goal, were laid to rest in the minds of the Tigers and their fans.

This article appeared in “Tigers By The Tale: Great Games at Michigan and Trumbull” (SABR, 2016), edited by Scott Ferkovich. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com were also accessed.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET193409100.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1934/B09100DET1934.htm

Auker, Elden, with Tom Keegan. Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006).

Greenberg, Hank, with Ira Berkow. The Story of My Life (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001).

Levine, Peter. From Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Rosengren, John. Hank Greenberg, the Hero of Heroes (New York: New American Library, 2013).

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Detroit Times

Grand Rapids (Michigan) Herald

Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press

The Sporting News

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 2

Boston Red Sox 1

Navin Field

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.