September 17, 1955: Millers’ Bob Lennon breaks up no-hitter – twice in same game

The Minneapolis Millers produced a rich history in the American Association and in 1955 won their ninth pennant, tying them with the St. Paul Saints for the most first-place finishes since the league was formed in 1902.

The Minneapolis Millers produced a rich history in the American Association and in 1955 won their ninth pennant, tying them with the St. Paul Saints for the most first-place finishes since the league was formed in 1902.

However, the Millers had only one appearance in the Junior World Series, the postseason matchup between the champions of the Association and the International League. The series had been held off-and-on and was mostly off in the 1910s when Minneapolis had some of its most powerful teams.

The Millers made the Junior World Series in 1932, when they were victimized by the Play of Six Decisions and lost to the Newark Bears.1 Soon after, the American Association went to a four-team playoff to determine its representative to the Junior World Series. Through 1954, Minneapolis had failed to get beyond the first round of those playoffs.

In 1955, though, the Millers set a league record by hitting 241 home runs in what would be their final season at 60-year-old Nicollet Park. This time, they followed up on a first-place finish by beating the Denver Bears in the opening round of the playoffs and then taking the first two games in the next series, against the Omaha Cardinals.

Game Three was on Saturday night, September 17, in Omaha, and it was scoreless after six innings. Cardinals starter Stu Miller had yet to allow a hit when he faced Monte Irvin, leading off the Minneapolis seventh. Irvin checked his swing on a 0-and-1 pitch, and home-plate umpire Eddie Taylor called it a ball. Bob Stewart, the umpire at third, signaled that Irvin had swung. Miller came off the mound to ask Taylor why he didn’t accept Stewart’s signal. Taylor, invoking a league rule calling for the automatic ejection of any pitcher protesting a ball or strike decision, threw Miller out of the game.

Tom Briere of the Minneapolis Tribune wrote, “Omaha fans screamed, threw pillows and threatened to riot at Taylor’s decision to remove Miller when he had not yet yielded a hit.”2 Bob Beebe of the Tribune added, “It took three policemen to pack off one large, unsteady individual who charged out to the diamond.”3

Omaha General Manager Bill Bergesch asked the umpires to consult with American Association President Ed Doherty, who was in the box seats. From this conference came a reversal of the decision. Miller was allowed to stay in the game, and the pitch in question was changed to a strike.4 Doherty later claimed that he did not overrule Taylor, but that Taylor decided on his own to override the ejection.

Beebe quoted Doherty: “The question is: Did Miller protest the decision? The version I have is that Miller merely said: ‘Why don’t you ask Stewart?’ He called it a strike.’” Beebe either wrote or quoted Doherty as such: “If Miller really protested he rightfully should be put out under the league rules, but that is something that will have to be determined.”5

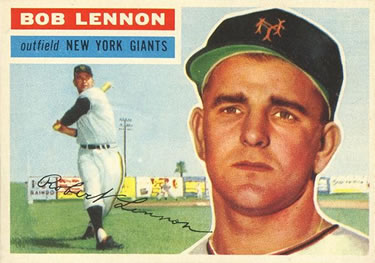

When the game resumed — Minneapolis manager Bill Rigney announced he was lodging a protest — Miller retired Irvin and Rance Pless. He then lost his no-hitter and shutout when Bob Lennon, who had hit 64 home runs for Nashville in the Southern Association the previous year, sent a towering fly over the 380-foot mark in left-center.

The Millers’ Whitey Konikowski, also pitching well, had given up only two hits until Omaha catcher Dick Rand homered with one out in the eighth to tie the game. One out later, Wally Lammers singled and Don Blasingame homered to right. The scoring ended there, Omaha coming away with a 3-1 victory to pull within one game of the Millers in the series.

With Minneapolis’s protest still pending, Doherty called Rigney, Omaha manager John Keane, and the four umpires together for a midnight conference at a downtown hotel, at which time Doherty overturned the earlier decision and upheld the protest, ordering the game replayed from the seventh inning on, with a 1-and-1 count on Irvin, and Stu Miller ejected from the game. Miller’s no-hitter was once again intact, although he would not be allowed the chance to complete it.

Briere reported that Doherty said of his earlier on-the-spot decision, “I acted in wisdom, not in fact, in order to prevent a riot.”6

Omaha immediately protested Doherty’s decision, appealing the ruling to the directors of the other American Association clubs, but the directors backed Doherty. The Cardinals protested again, just before the start of the game that afternoon, on the grounds that “not sufficient time was taken in arriving at a decision on Rigney’s original protest.” This final challenge did not worry the Millers as it would require a meeting of the executive board of the minor league, which was not scheduled to convene for several months, to rule on Omaha’s latest appeal.7

The Millers took advantage of the favorable ruling on their protest. When the protested game in Omaha resumed on Sunday afternoon after a 38-minute rain delay, Bob Tiefenauer took Stu Miller’s place on the mound and assumed the 1-and-1 count on Irvin.8 Irvin grounded Tiefenauer’s first pitch to shortstop Dick Schofield, who booted it for an error. Pless sacrificed, bringing up Lennon, whose home run the night before, erased from the official records by the protest, had been the first hit for the Millers.

This time he tripled off the center-field fence 400 feet away — narrowly missing another home run — to score Irvin and give himself the possible distinction of being the first player to ever break up a no-hitter twice in the same game. Memo Luna relieved Tiefenauer, and Dave Garcia hit for Carl Sawatski. Garcia beat out a squeeze bunt for a single, which also scored Lennon.

The Millers added five runs in the eighth and won 7-2. They also won the regularly scheduled game, 7-3, to sweep the four-game series and move on to the Junior World Series for the first time since their 1932 encounter with Newark.

Robert G. Phipps, an Omaha-based writer and correspondent for The Sporting News, quoted Walter Shannon, farm director of the parent St. Louis Cardinals, as calling Doherty’s upholding of the protest “the worst I’ve witnessed in 30 years in baseball.”

Phipps also had Shannon saying to Doherty, “You can’t be right both in your decision at the time and in the rump session in a hotel room. By your own information to managers you said that all protests would be settled on the field immediately. Now you have gone against yourself with this action, and you have gone against yourself with this action and you have also reversed your umpires.

“You said you ordered Miller back in the game to prevent a riot. It’s not your job to control riots at the Omaha ballpark. That’s the job of Bill Bergesch and the Omaha police department.”9

Doherty’s handling of the situation was abominable. Regardless of whether or not it was appropriate for Miller to be ejected, Doherty either made or allowed a decision to be made that he was not prepared to stick with in a later meeting. As such, he allowed Minneapolis two chances to win the game.

Had the Millers won the game after it resumed on Saturday night, the protest would have been irrelevant. But Doherty created a situation in which Omaha had to win twice — on Saturday night and again on Sunday.

Aided by the protest, the Millers became the first team in American Association history to win eight straight playoff games. They made it nine in a row with an opening victory in the Junior World Series vs. the International League champion Rochester Red Wings. The series went the limit with the Millers winning the decisive seventh game, a game that also marked the end for 60-year-old Nicollet Park.

Doherty the Center of Protest Storms

The protest wasn’t the first, or the last, that Doherty had to administer involving some of the participants. In the 1954 American Association playoffs. Keane, then managing the Columbus Red Birds, protested Stewart’s decision to not eject Louisville manager Mike Higgins for coming out of the dugout after Colonels pitcher Bill Werle claimed that a Columbus batter had swung at a third strike. Doherty rejected Keane’s protest, ruling that Higgins hadn’t disputed the decision but “only sought to send Werle back to the mound and keep him out of trouble.”10

Minneapolis and Omaha had created a protest in 1955 prior to the playoffs. In the top of the ninth on August 23, the Millers scored eight runs for an apparent 16-13 win. Rigney pinch-hit during the uprising. Keane protested, noting a rule prohibiting a player-manager from being placed on the active list more than once during a season. Rigney had previously been activated. Doherty, acknowledging his part in allowing Rigney’s name on the active roster, declared him ineligible and ordered the game replayed from the point of protest, with the score 13-13. The game resumed two nights later, and Don Bollweg hit a three-run homer as the Millers won 16-14.11

The 1959 playoffs between Omaha and Minneapolis brought Doherty yet another headache. In Game Five, at Metropolitan Stadium in a Minneapolis suburb (where the Millers had moved after Nicollet Park closed), a young second baseman, activated by the Millers just before game time to replace service-bound Lee Howell, hustled home with the winning run in the last of the 10th, sparking a rhubarb in which Omaha pitcher Frank Barnes had to be restrained from attacking umpire Tom Bartos.

Bartos’s decision on the play stood, but after the game Bergesch announced he was protesting the game for another reason, questioning the eligibility of the new second baseman. Ruling that the player had not been certified for eligibility until September 18, Doherty upheld another Minneapolis-Omaha protest and ordered the entire game replayed.

The next night the Millers won the replayed game, as well as the regularly scheduled one, to capture the league semifinal series without the services of their new second baseman, Carl Yastrzemski.12

With Yaz officially eligible two days later, the Millers went on to defeat the Fort Worth Cats for the league championship before losing to the Havana Sugar Kings in seven games in the Junior World Series.

Omaha dropped out of the American Association after the 1959 season.Thirteen months later, Calvin Griffith’s announcement that he would transfer the Washington Senators franchise to Minnesota signaled the end of the Minneapolis Millers.

Ed Doherty was one man who would not miss them.

Sources

Minneapolis Tribune sportswriter Tom Briere’s scorebook is the source of the play-by-play information.

Notes

1 Stew Thornley, “Minneapolis Millers Come Up Short on Play of Six Decisions,” SABR Baseball Games Project, sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-5-1932-minneapolis-millers-come-up-short-on-play-of-six-decisions/, accessed June 5, 2020.

2 Tom Briere, “First in History to Win Eight Straight in Playoffs; Facts on Protests,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 19, 1955: S-1.

3 Bob Beebe, “Omaha Raps Millers, 3-1, on Homers, Minneapolis Tribune, September 18, 1955: 1.

4 Robert G. Phipps, “Omaha Rhubarb Spices Finale of Playoff in A.A.,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1955: 35.

5 The punctuation, or lack of it, in Beebe’s game story makes it unclear if the sentence beginning with “If Miller really protested … ” was Beebe’s words or if he was quoting Doherty.

6 Briere.

7 Briere.

8 “Millers Sweep Omaha Series: Face Rochester Wednesday,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 19, 1955: S-1.

9 Phipps.

10 “Omaha Also on Losing End of Playoff Protest in 1954,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1955: 35. The headline incorrectly referred to Omaha, although it apparently was referring to Keane, who was involved in playoff protests in 1954 and 1955. Adjacent to Phipps’s story in The Sporting News, the sidebar itself did not have a byline.

11 Stew Thornley, “Millers Topped Minors in Odd Protested Games,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1984. research.sabr.org/journals/millers-topped-minors-in-odd-protested-games.

12 Stew Thornley, “Minneapolis Millers Protested Games,” stewthornley.net/millers_protests.html.

Additional Stats

Minneapolis Millers (1) 7

Omaha Cardinals (3) 2

Omaha Municipal Stadium

Omaha, NE

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.