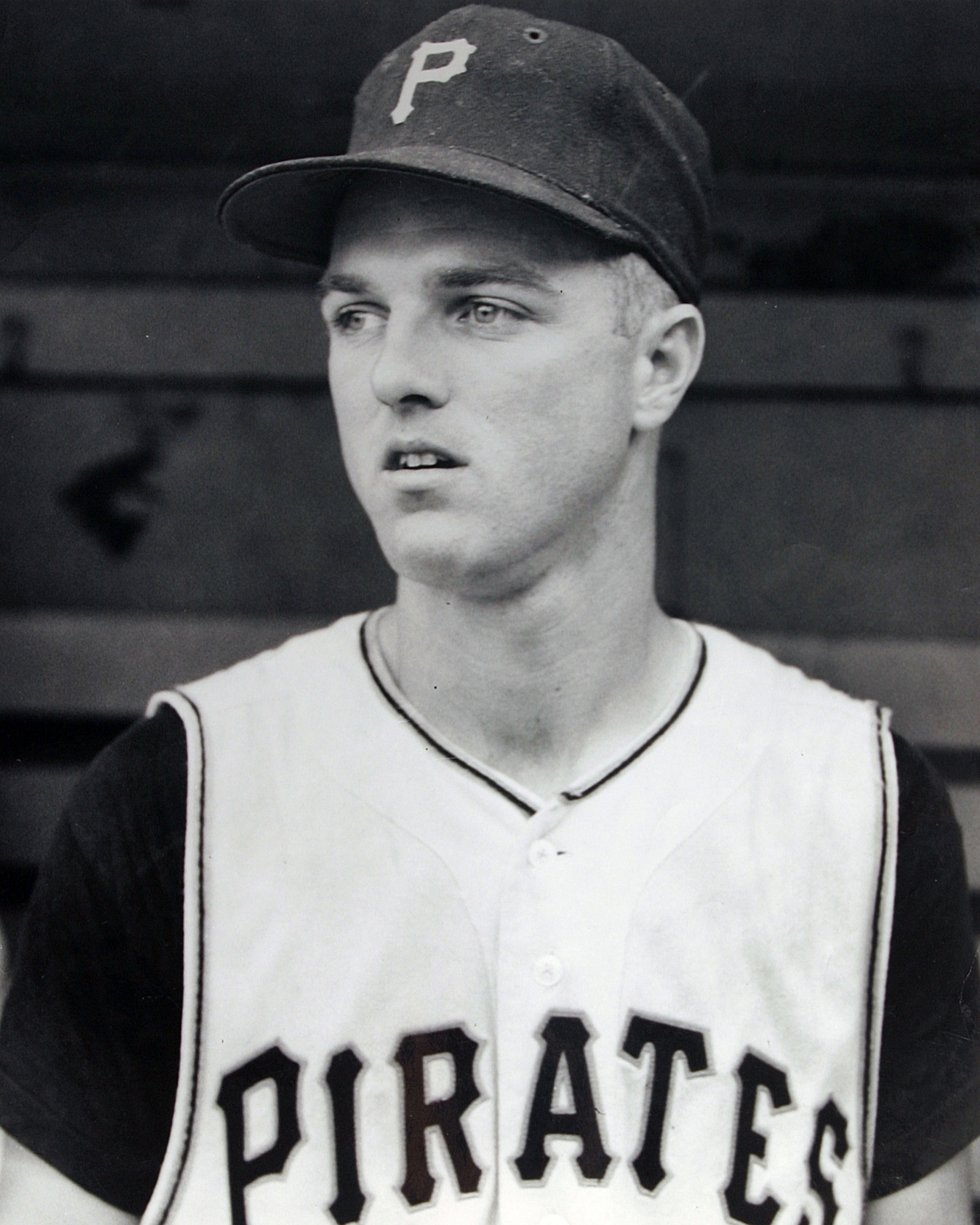

Dick Schofield

Dick Schofield spent 19 years in the big leagues working for seven teams as a versatile utility player. Born on January 7, 1935, in Springfield, Illinois, to John and Florence Schofield, John Richard “Dick” Schofield was the second in a succession of four generations of professional baseball players. His father, John “Ducky” Schofield, played ten minor-league seasons, also with seven different teams. He finished up in 1938 with Springfield of the Three-I League. A shortstop like his son, the diminutive elder Schofield batted .234 in a career in which he was noted more for his glove work than his bat.

Dick Schofield spent 19 years in the big leagues working for seven teams as a versatile utility player. Born on January 7, 1935, in Springfield, Illinois, to John and Florence Schofield, John Richard “Dick” Schofield was the second in a succession of four generations of professional baseball players. His father, John “Ducky” Schofield, played ten minor-league seasons, also with seven different teams. He finished up in 1938 with Springfield of the Three-I League. A shortstop like his son, the diminutive elder Schofield batted .234 in a career in which he was noted more for his glove work than his bat.

In Springfield the Schofield family took up farming. “Everyone here were farmers,” said Dick. “We weren’t very good ones I suppose, but that’s what everyone in Springfield did.”1 Growing up as an only child, Dick benefited by the coaching and constant practice sessions provided by his father. By the time he was going to Springfield High School, he was the best player in the region. “One night after a game, a couple of Dodgers scouts asked me if I was intending to sign after what they thought was my senior year,” said Schofield. “I informed them that I was just a freshman. I thought I was kind of hot stuff.”2 In his junior year, 1952, Schofield led Springfield to the Illinois Junior American Legion Championship. After he graduated he had the choice of going to Northwestern University on a basketball scholarship or signing with 14 of the 16 major-league teams.

A lifelong Red Sox fan, Schofield preferred to sign with Boston but the club had just signed some other expensive players, including shortstop Don Buddin. The best offer, as it turned out, came from the St. Louis Cardinals. Scouts Joe Monahan and Walter Shannon made the 18-year-old shortstop the Cardinals’ first bonus baby when they signed him to a $40,000 bonus contract in June 1953. Fourteen players signed that year for bonuses of more than $6,000.3 Under the rules of the day, such bonus players were required to spend two years on the major-league roster.

Just weeks out of high school, Schofield reported to the Cardinals. When teammates learned his father’s nickname, Ducky, they started calling the youngster by the same name. (His father had gotten the nickname when he was growing up in Linwood, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, where seeing flocks of the birds was common. The nickname stuck with Schofield throughout his career although it was just as common for teammates to call him Schoy, pronounced Sko-ee.) “I pretty much kept to myself and didn’t socialize with the other players,” remembered Schofield the younger. “It was a veteran team and there were those that resented me taking up someone’s spot on the roster.”

Although he didn’t get into a game for a few weeks, Ducky did see action of a different kind. On June 25 the Cardinals took on the Giants in St. Louis. In the second inning, Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky came out of the dugout to argue with umpire Augie Donatelli. First one towel and then another came flying out of the Cardinals dugout. As Stanky made his way down the dugout steps, Donatelli warned that if another towel came out, an ejection would follow. “I’m just sitting there quietly watching and Stanky comes back and says, ‘Schofield, throw a towel.’ Of course he knew I wasn’t going to play anyway so it didn’t matter to him if I got tossed,” recalled Schofield. “So I threw the towel and Donatelli came over and said, ‘Who threw that towel?’ “Stanky pointed to me and said, ‘Schofield!’ “I was ejected before I had ever gotten into a box score.” It was the only ejection of his career.

On July 3 in Chicago, Schofield finally got into his first big-league game when he pinch-ran for Del Rice in the seventh inning of a 10-3 loss to the Cubs. Playing time was tough to come by and, although he was in the big leagues, Schofield would have rather been playing every day in the minors. Stanky did the best he could to make the season a learning experience for the rookie. “He always would come around and ask me questions during the game and point things out,” said Schofield. He was probably the smartest manager I ever had.” On July 17, Ducky got his chance to bat in the first game of a doubleheader in Brooklyn. After coming in defensively in the bottom of the fifth inning of a Dodgers blowout, Schofield led off the sixth with a line single to left field off southpaw Johnny Podres. Nearly a month later, on August 16 in Cincinnati, Schofield hit his first home run when he connected against Frank Smith. On the 26th the rookie circled the bases again, this time off the Giants’ Jim Hearn at the Polo Grounds. Schofield wouldn’t homer again until 1958. In September he batted only once and his final seven appearances of the season were as a pinch runner. In all, he appeared in 33 games and gathered 41 plate appearances. In 1954 the bonus baby saw even less action. Despite being with the club all season, Schofield played in only 43 games and came to the plate just seven times. Often used as a pinch runner, he scored 17 runs. During the offseasons he attended Springfield Junior College.

Freed of the bonus-baby restriction that required him to spend his first two years on the Cardinals’ bench, Schofield spent the next two seasons as the starting shortstop for Omaha of the American Association, St. Louis’s top farm club. Each year he earned a September call-up to the Cardinals. Playing for manager Johnny Keane at Omaha, Ducky responded with batting averages of .273 and .295 while continuing to play exceptional defense. In 1956 he hit 11 home runs and had 57 RBIs, both career highs. His most memorable highlight of the 1956 season came on June 16, when he wed Donna Jean Dabney.

Schofield thought he was going to be the Cardinals starting shortstop in 1957, but his plans were derailed when newly acquired veteran Al Dark refused to move to third base. “Dark got there in June of ’56 and the plan was for Ken Boyer to move to center, Dark to play third and me to play short the next year,” recalled Schofield. “Dark didn’t want to play third so he stayed at short and rookie Eddie Kasko was handed the third base job.” It became apparent that Schofield’s future in St. Louis was limited. He spent the entire season with the Cardinals but was used mostly as a pinch runner and defensive replacement; he played in 65 games and had only 56 at-bats.

Early in the 1958 season Dark was traded away, Boyer went back to third base, Curt Flood became the center fielder, Kasko moved to shortstop and Schofield was obviously expendable. On May 13 he got a parting gift from the Cardinals when he had a bird’s-eye view from the on-deck circle of Stan Musial’s 3,000th hit. At the June 15 trading deadline, Schofield was shipped to the Pittsburgh Pirates with cash for infielders Gene Freese and Johnny O’Brien. The prospects of becoming an everyday player weren’t any better in Pittsburgh; Schofield found himself behind Dick Groat, who was entrenched as the club’s regular shortstop.

On May 26, 1959, Schofield was in the starting lineup and leading off for the Pirates against the Braves in Milwaukee. Harvey Haddix was pitching for Pittsburgh. Schofield had become friends with Haddix when they were teammates with the Cardinals. The Pirates left-hander pitched 12 perfect innings but lost when the Braves scored the only run of the game in the bottom of the 13th. Schofield had a game-high three hits as the Pirates rapped out a dozen singles but still couldn’t score. His third-inning single would have driven in a run if Roman Mejias had not been thrown out trying to advance from first to third on an infield hit by Haddix. Schofield’s hit sent Haddix to third but there were two outs instead of one; Bill Virdon flied out and Pittsburgh didn’t score. Schofield had also contributed with his glove, making a long throw from the hole in the sixth inning to just nip Johnny Logan at first. “That was a bizarre, pressure-packed game,” Schofield lamented. “It was just a shame that we couldn’t score for him.”4

In September 1960, Schofield enjoyed the greatest month of his career. The Pirates were locked in a pennant race when on September 6 Groat’s wrist was broken when he was struck by a pitch from Braves pitcher Lew Burdette. He was lost for the rest of the season. Groat was the team captain and, despite the injury, won the National League batting title and was named the Most Valuable Player. Little Dick Schofield filled the big shoes and then some. After the injury to Groat that day, he came into the game in an 0-for-18 slump and without a hit since May 31. He proceeded to collect three hits to lead the Pirates to a 5-3 win. He played the rest of the season, batting .403 (27-for-67) and getting at least two hits in a game eight times. During their final 22 games, the Pirates had a stretch of three straight doubleheaders (September 18, 20, and 22). Schofield played every inning of all six contests as the Pirates swept all three twin bills to effectively wrap up the pennant. He went 10-for-19 in those games. It was the Pirates’ first pennant since 1927. The World Series against the New York Yankees was bittersweet for Schofield. Although the Pirates won in dramatic fashion, he was barely a part of the effort. Before the start of the Series, Groat proclaimed himself healed and ready to play. He later admitted that he had to catch nearly everything barehanded but hid that fact because he didn’t want to miss the Series. He batted .214. Schofield was disappointed but said he understood the decision. “I thought I deserved to play, but I understand why Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh played Groat,” he said. “We really both deserved to play.” The only action seen by Schofield was three meaningless pinch-hitting appearances in Yankee blowouts. He had a single in Game Two, a 16-3 loss, and made outs in Game Three’s 10-0 loss and Game Six, a 12-0 shutout. After pinch hitting, Schofield stayed in the game to spell Groat defensively in Games Two and Six.

His September success in 1960 didn’t earn Schofield any additional playing time. He remained a utility player and filled in at second, third, and short as well as seeing some action in the outfield. In 1961he appeared in 60 games and the next season in 54.

After waiting ten seasons to become a big-league starter, Schofield finally got his chance in 1963. An offseason trade sent Groat to St. Louis and Ducky was named the starting shortstop and leadoff hitter. He was in the Pirates’ Opening Day lineup for each of the next three seasons. In 1963 he set career highs in nearly every offensive category. He played in 138 games and had more than 600 plate appearances. His .246 batting average was fourth among National League starting shortstops. He drew 69 walks to help justify his batting in the leadoff spot. On April 17, 1964, Schofield became the first batter to come to the plate at Shea Stadium in New York. He popped out to second baseman Larry Burright to inaugurate the Mets’ new ballpark as the Pirates won. 4-3. Schofield duplicated his .246 average that season but played in 17 fewer games. The most memorable of his three openers was in 1965 when Bob Bailey hit a tenth-inning homer off Juan Marichal to give Bob Veale and the Pirates a 1-0 win in Pittsburgh. Less than two months later, Schofield would be Marichal’s teammate. On May 22 the Pirates traded him to the Giants for infielder Jose Pagan. The already offensively loaded Giants upgraded their defense and the Pirates opened up the shortstop job for Gene Alley. Schofield provided the defense the Giants were looking for as he led the league in fielding percentage. However, he batted just .203 after coming to San Francisco and .209 for the season. This was Schofield’s best chance to be the starter on a World Series team. The Giants held a four-game lead over the Dodgers on September 20 with 12 games to play. They had won 17 of their last 18 games and appeared poised to take the pennant. But the Giants went 5-7 the rest of the way and the Dodgers went 11-1 to win the pennant title by two games. “We should have won,” agonized Schofield. “All we had to do was win a couple of more games and we couldn’t do it. That was a terrific team.”

Tito Fuentes was called up in August and played well for the Giants, so when the 1966 season started, Schofield was relegated to a utility role. In May his contract was purchased by the New York Yankees. “Houk brought me in to play short,” said Schofield of Yankees skipper Ralph Houk, “But I just couldn’t get healthy. I’m not sure what it was, but my arm just swelled up and I couldn’t throw.” By the time Schofield was ready to play, Horace Clarke was playing shortstop for New York. On September 10 Schofield was traded to the Dodgers for pitcher Thad Tillotson and cash. It was his third team of the 1966 season. When he arrived in Los Angeles as the club’s fifth switch-hitter, manager Walter Alston told him he would be the Dodgers’ third baseman. Schofield hadn’t played third since 1963. John Kennedy and Junior Gilliam had shared the Dodgers’ third-base chores all season but both were banged up. “I played every day at third down the stretch and we ended up winning the pennant,” recalled Schofield. “The tough part was that I got there after the trade deadline so I wasn’t eligible to play in the series.” The Dodgers were swept by the Orioles in the World Series. In 1967 the Dodgers were a shell of the club that had won two straight National League pennants. Sandy Koufax retired and Maury Wills had been traded to Pittsburgh. Schofield shared the shortstop job with Gene Michael but hit just .216. Michael hit .202 on a Dodgers club that was last in the National League in batting. Los Angeles tumbled all the way to eighth place with a 73-89 mark. In December the Dodgers released Schofield.

The World Series champion Cardinals invited Ducky to spring training in 1968 and he signed with the club on April 1. In his second tour of duty with St. Louis, Schofield settled into a utility role. He started 13 games at shortstop and 17 at second base while appearing in a total of 69 games for the pennant-winning Cardinals. He appeared in two World Series games but did not get to the plate as the Cardinals bowed to the Tigers in seven games. In December Schofield was on the move again; the Cardinals sent him to the Boston Red Sox for pitcher Gary Waslewski.

Schofield never felt more comfortable in a utility role than he did with the Red Sox in 1969. Playing mostly second base, he also filled in at shortstop and third base and even ended up in left field and right field a few times. He started 44 times but appeared in a total of 94, his most since 1965. “Dick Williams was a good manager,” Schofield said. “Every day when I came to the park, I knew I would probably play. I was the first pinch-hitter off of the bench after the seventh. Williams liked it that I was a switch-hitter and he could use me in double switches because I played several positions.” Schofield responded by hitting .333 (11-for-33) in a pinch-hitting role. His average was third best in the American League among players with at least 30 pinch at-bats, and his nine pinch RBIs were fourth best in the league. With nine games left in the season, Dick Williams was fired as manager. Eddie Kasko became the manager in 1970 and everything changed for Schofield. “I didn’t get to play in the field much under Kasko and I never knew when I was going to pinch-hit,” he recalled. “I could be in the game to hit in the fourth or fifth inning at a meaningless time. I never really could get into any kind of rhythm.” He hit only .163 (7-for-43) in 1970 as a pinch batter. Only two American League hitters with at least 30 at-bats were worse. In October the Red Sox traded him back to the Cardinals for first baseman Jim Campbell.

Now 36 years old, Schofield started the 1971 season with the Cardinals and on May 11, he hit the last of his career 21 homers. It came off Carl Morton in Montreal. He later accepted an assignment to Triple-A Tulsa, which lasted just 18 games. On July 29 Schofield was traded again, this time to the Milwaukee Brewers along with outfielder Jose Cardenal and pitcher Bob Reynolds for minor league pitcher Charlie Loseth and infielder Ted Kubiak. His final game in the big leagues came on September 30, 1971, as the Brewers lost to the White Sox 2-1 in Chicago.

After the season the Brewers gave Schofield the choice of managing San Antonio in the Texas League or playing another season with Milwaukee. He chose playing in the big leagues but became a victim of baseball’s labor wars. With a strike looming during spring training, teams were releasing veterans and not keeping unsigned players. “One day in Tempe our manager Dave Bristol comes up and tells me ‘Dick, I think you’re in trouble,’ ” said Schofield. “Sure enough, a couple of days later I was released.” Players went on strike on the last day of spring training and the first ten days of the season were wiped out. The 37-year-old Schofield’s 19-year career was over. He had entered the game in 1953 as one of baseball’s youngest players. When he left baseball in the spring of 1972, he was one of the oldest. In a testament to his versatility, he was used as a pinch-runner 190 times and as a pinch-hitter in 283 games.

Through the years he had opportunities to return to the game as a coach but instead decided to go home to Springfield. “I had been away from my home and family for so long, it just felt right that I should be with them,” Schofield said. So he went home to his wife, Donna, and their three children, Dick, Kim, and Tammy. Son Richard “Dick” Craig Schofield went on to a 14-year major-league career. His father’s choice of returning to Springfield played a large role in young Dick’s ability to make it in baseball. “I did the same thing my dad did,” beamed the elder Schofield. “I threw him a million baseballs, live batting practice. His sisters would shag balls.”5 “In all of my years in baseball, my greatest day was when I watched Dick take the field in the big leagues for the first time.”6 The girls were also fine athletes. Kim was a track star at the University of Florida and competed in the 1976 Olympic trials. Tammy excelled on the links as an excellent golfer.

Kim’s son and Dick’s grandson is Jayson Werth, who was also born in Springfield. He is the fourth generation of professional ballplayers in the family. Werth, an outfielder, was with the Washington Nationals in 2012, his tenth big-league season. He is the stepson of former major-league first baseman/catcher Dennis Werth.

In 1975 Schofield began a 23-year career as a salesman for Jostens, which makes class rings, yearbooks and awards such as championship rings. From 1983 to 2003 Schofield served on the board of the Springfield Metropolitan Exposition Authority, which runs the local convention center. He resigned from the board to spend more time at home with his wife, Donna, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Dick Schofield died at the age of 87 on July 11, 2022.

Notes

1 Dick Schofield, telephone interview with author, May 10, 2011. Unless otherwise indicated, all of Schofield’s quotes are from this interview.

2 Danny Peary, We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 216.

3 Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 99.

4 Peary, 435.

5 Paul Povse, St. Louis Beacon, http://www.stlbeacon.org/issues-politics/112-region/12691, accessed February 12, 2012.

Full Name

John Richard Schofield

Born

January 7, 1935 at Springfield, IL (USA)

Died

July 11, 2022 at Springfield, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.