September 20, 1973: Mets get ‘all the good bounces’ and move closer to first place

They had been in the wrong place, but at the right time.

They had been in the wrong place, but at the right time.

The 1973 Opening Day roster weakened under the weight of countless ailments. Right fielder Rusty Staub continued to deal with the hamate bone operation that curtailed his wonderful start to 1972. Catcher Jerry Grote, shortstop Bud Harrelson, first baseman John Milner, and left fielder Cleon Jones each missed significant chunks of the schedule—causing daily lineup cobbling with such a lack of stability.

On July 9, the Mets were 34-46. They were sixth in a six-team division—12 ½ games out of first. “Who Should Mets Ax?” was the headline of a New York Post poll that ran during the summer swoon—with manager Yogi Berra, general manager Bob Scheffing, and team chairman M. Donald Grant as choices. The majority put their support behind Berra, given a bad hand with the preponderance of injuries and an unstable bullpen. Nevertheless, rumor had it Grant was considering offering Yogi the pink slip as his team sat in the NL East cellar.

A condition like this prompted the buoyant Berra to generate his most renowned pearl of wisdom: “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.” Both the team, and its manager, were knocked down—but certainly not out. As those key pieces were coming back to full service, the rest of the middling divisional conglomerate was generous enough so that the Mets weren’t left too far astray.

There was no separation of power typical of most pennant races, where the better teams pull away as the bad ones fail to keep up. Instead, mediocrity was spread all around. For the Mets, who received their clean bill of health by late August, this had the makings of an 11th-hour revival.

Even as September beckoned, New York sat in the cellar—yet only 6 ½ games back. The greater hindrance was in the number of teams they had to pass instead of the ground to make up. Embarking on what would be a 21-8 stretch, the Mets caught and passed other NL East teams still going in quicksand. After September 19, the fight for the title was as congested as the Van Wyck Expressway. Pittsburgh led, but had three teams breathing down its neck—the Expos one game behind, and the Cardinals and Mets each 1 ½ back.

The Mets, though, were in a more advantageous position vis-a-vis the other pair chasing for first. New York was in the midst of a five-game home-and-home series with the Bucs and were coming off two straight victories to gain ground.

But a see-saw tradeoff of single-run innings appeared to end in Pittsburgh’s favor. The Pirates went on top, 3-2, on Dave Cash’s double off Harry Parker—who came in relief of Jerry Koosman. It seemed the Mets’ uphill climb toward the NL East summit would take an inopportune setback. With two outs and Ken Boswell at second, the likelihood of that obstacle increased. However, New York’s offense got to reliever Ramon Hernandez for the second time in three nights. It was Duffy Dyer who made it happen—a double to left field that erased the Mets’ third deficit, sent the game into extra innings, and unearthed the remnants of good fortune that emanated during the miracle march of four years prior.

In 1969, it came in the form of a black cat scooting behind home plate and in front of the faltering Chicago Cubs dugout. In ’73, Lady Luck lent her generous magic hand with a singular play. A play that couldn’t possibly be duplicated. A play so distinctive it earned a catchy moniker.

That play came in the top of the 13th.

With two outs and Richie Zisk on first, Dave Augustine hit one destined for the Mets bullpen. The ball’s trajectory, though, sent it squarely off the top of the left-center field fence and back towards Cleon Jones. An inch further, and it’s a home run. An inch shorter, and what followed wouldn’t be possible.

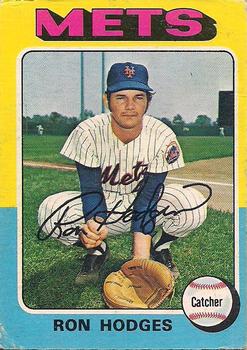

Jones caught it from the fortuitous bounce, turned, and fired to cut-off man Wayne Garrett while Zisk—the potential go-ahead run—rounded third and headed home. Garrett threw to catcher Ron Hodges, perched the plate, who caught it and laid down the tag on a sliding Zisk.

“I knew I had to catch the ball and hold onto it, but I didn’t have all that much time,” Hodges said. “I had to block the plate….I squeezed the baseball as hard as I could squeeze it. I didn’t want to drop it.”1

Home plate umpire John McSherry, after waiting a few moments to confirm, elevated his hand and closed it into a fist. Side retired—thus solidifying the “Ball on the Wall” play.

”Believe it or not, I had it in line all along, I thought it would hit the wall,” Jones said, “Luckily, Garrett was at short. If Harrelson had been there, he would have taken the relay much further in the outfield and we would never have gotten Zisk.”2

Minutes later, the Mets made good on this stroke of wondrous luck.

Walks to Milner and Boswell, followed by Don Hahn’s failed bunt try brought Hodges back to the forefront with one out. Hodges singled against Dave Giusti and just in front of left fielder Willie Stargell to score Milner and pull New York within a half-game.

The following day’s report in the New York Times wrote that the Mets had endured a “season that has seem them hurt, slumping, vilified, and resurrected at various stages. But with all their adventures, they will probably remember last night’s four-hour thriller as one of the top soap operas of the year.”3

Roughly 24 hours later, New York won again to reach .500…and first place—completing its three-week ascent from bottom to top.

That’s where the Mets would stay. They prevailed in five of next seven contests—and Cleon Jones was a significant reason why. He hit six home runs over the final two weeks, including one in the first of a presumed October 1 doubleheader at soggy Wrigley Field, played a day beyond the scheduled end to the regular season, with New York needed one victory to clinch.

The Mets built a 6-2 lead in support of eventual Cy Young recipient Tom Seaver, but their ace tired—evidenced by Rick Monday’s two-run blast over the ivy—and gave way to 1973’s late-year inspiration.

Tug McGraw, countering his dreadful first half with a remarkable second half, saved games—and the season. When he got Glenn Beckert to pop softly to John Milner—who then stepped on first to double off Ken Rudolph, running on contact—for a game-ending double play, Tug ensured that this season would continue.

It was far from conventional, but it was definitely official. At 82-79, the worst record (at the time) for any divisional winner, the New York Mets emerged victors of this NL East slog.

This article was published in “Met-rospectives: A Collection of the Greatest Games in New York Mets History“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Brian Wright and Bill Nowlin. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the reference cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Ultimatemets.com.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN197309200.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1973/B09200NYN1973.htm

Notes

1 Howard Blatt, Amazin’ Met Memories (Tampa: Albion Press, 2002), 265.

2 Craig Wolff, “1973 Mets Revive a Month of Glory,” New York Times, July 31, 1993: 1.

3 “Mets Rally Three Times, Beat Pirates in 13th, 4‐3,” New York Times, September 21, 1973: 1.

Additional Stats

New York Mets 4

Pittsburgh Pirates 3

13 innings

Shea Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.