September 21, 1861: Harry Wright plays his first base ball game as a professional

In the early 1860s, issues of the New York Clipper, the self-proclaimed “American Sporting and Theatrical Journal,” were riddled with announcements of “benefits” held for performers of all sorts.1 Actors and singers retained the proceeds from special performances staged to augment their meager incomes,2 boxers sparred before paying crowds to make ends meet between prizefights,3 and professional racket ball players competed in tournaments with proceeds funneled to participants.4 Cricket clubs also staged benefits to raise funds for professionals in their ranks.5

In the early 1860s, issues of the New York Clipper, the self-proclaimed “American Sporting and Theatrical Journal,” were riddled with announcements of “benefits” held for performers of all sorts.1 Actors and singers retained the proceeds from special performances staged to augment their meager incomes,2 boxers sparred before paying crowds to make ends meet between prizefights,3 and professional racket ball players competed in tournaments with proceeds funneled to participants.4 Cricket clubs also staged benefits to raise funds for professionals in their ranks.5

In early September of 1861, the New York Dispatch announced plans for such an event on the grounds of the St. George Cricket Club in Hoboken, New Jersey: a benefit for their veteran cricketer Sam Wright and his son, Harry.6

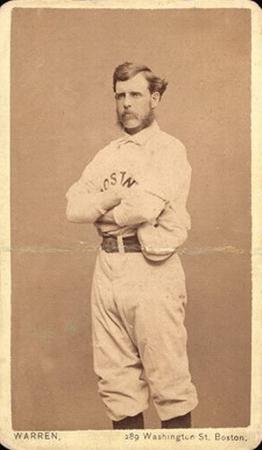

Sam Wright was arguably the best cricketer in all of England when he moved to the United States in 1837 to play for the St. George Cricket Club of New York. He starred for St. George over the next two decades, joined on the pitch in the late 1840s by the not-yet-teenage Harry. Sam was a jack-of-all-trades, playing where needed and serving as the club’s groundskeeper.7 By 1861, the 26-year-old Harry was drawing compensation as a professional for St. George, as his father long had, and praise as “the most promising cricketer among us.”8 He was also playing base ball for the Knickerbockers of New York.

The Wrights’ cricket benefit was a match between 11 English-born players from the St. George Club and 22 cricket-playing Americans “selected from the crack fielders of the leading [Brooklyn and New York City] Base Ball Clubs.”9 With the Americans having double the usual number of fielders and batters, the New York Clipper viewed them as doubling their chances of emerging victorious.10

An advance notice for the Wrights’ benefit, published by the New York Atlas on September 15, noted that after the cricket match, nine of the 22 Americans “will play a game of Base Ball against any nine that can be brought on the ground, or any eighteen Old Countrymen.”11 By the eve of the cricket match, the ensuing base ball game was being billed as a contest “between nine base ball players and eighteen cricketers for the benefit for Harry Wright, catcher of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club.”12 No reason was given in newspapers that covered the base ball game for why Wright was its beneficiary. That omission suggests he was being compensated for his performance on the base ball diamond, rather than for some personal loss, which surely would have been shared in order to drum up attendance, had redress been the benefit’s purpose.

Advertised base ball matches before this one had been played for “the honor of victory,”13 for a trophy (often the game ball), for a meal, occasionally for prize money or sometimes to benefit community members who’d fallen on hard times, but not for the purpose of channeling funds to an active base ball player.14 Prominent base ball players had been getting compensated under the table for years,15 a practice considered merely unseemly at first, then made illegal after professionalism was banned by the National Association of Base Ball Players (to which the Knickerbockers belonged) in 1859.16 Unlike play-for-pay, benefits were considered honorable and so provided a means, however thinly veiled, to skirt the NABBP prohibition.

The Wrights’ benefit cricket match got underway on Saturday morning, September 20, with Harry leading the English eleven. His teammates included two of his three younger brothers, George, only 14 years old, and Dan, born the year after Harry was.17 The American side included prominent base ballers from various clubs based on the New York side of the Hudson River: Jim Creighton and Asa Brainard of the Excelsiors (base ball champions in 1860 who were idled by the Civil War in 1861),18 Atlantics captain Dickey Pearce, Knickerbockers president Thomas Dakin, Andrew J. Bixby of the Eagle club and a Whiting, presumably John, also of the Excelsiors.19 In an upset, the Americans prevailed over Harry’s English eleven in just under six hours.20

The plan for Sunday had been for nine of the best base ball players in the area to oppose 18 cricketers, but there weren’t enough of the latter available. Instead, a team of Eighteen was formed with nine cricketers from the St. George club; Harry Wright; his brother George; and seven other base ball players from the New York’s Mutuals, Harlems, and Gothams, plus one unnamed club.21 Recognizing that many of the cricketers lacked experience playing baseball, their side was allowed six outs per at-bat while the baseballers were limited to three. The extra outs, together with posting all their players on the field at one time, gave the Eighteen a fourfold advantage in the eyes of the Clipper.22

Twice as many spectators were on hand compared with the previous day’s cricket match by the time the base ball game got underway on a warm first day of autumn.23 Admission was 25 cents (equivalent to nearly $9 in 2023), with ladies admitted free of charge.24 Those who parted with another three pennies for a copy of the New York Times before the game would have found a front page entirely devoted to news of the war.

The Eighteen were first to bat, with the 20-year-old Creighton pitching from behind an iron plate set 45 feet from home plate, and Pearce his batterymate. The balance of the Nine were filled from the ranks of the Brooklyn-based Excelsiors (Andrew T. Pearsall, George Flanley, Whiting, and Brainard), Stars (Hope Waddell), Eagle of New York (Bixby), and Eureka of Newark, New Jersey (Edward R. Pennington).25 Former cricket journalist turned base ball gadfly Henry Chadwick served as the game scorer, with R. Oliver of the Excelsiors umpiring.26

Two runs were tallied by the Eighteen in the first frame, highlighted by “a magnificent hit to centre field” by H.B. Taylor of the Mutuals.

As the Nine first came to bat, the Eighteen took the field to create what the New York Clipper understatedly called “a novel sight.” Two players occupied each position other than pitcher, where Simon Burns of the Mutuals stood alone, and catcher, where Harry Wright was shadowed by a pair of cricketers.27 The other seven positions were manned by a base ball player, with a cricketer hovering nearby; the latter listed in box scores as either a second player or “cover” for that spot. At shortstop, by at least one account, was young George Wright.28

Leading off for the Nine was Pearsall, a medical student at New York’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. Born in Alabama, he would be wielding a surgeon’s knife for the Confederate army a year later.29 Pearsall singled and came around to score the Nine’s only run in their first turn at bat. The last two Nine batters in that inning were retired at first base on “poor hits to right field.”30

For the Eighteen’s second turn at bat, Brainard replaced Creighton, who moved to second base. Not a single batter reached base, as Brainard set down the side, all six of them, in order. Three hits and a home run to center field by Pearce put the Nine up 4-2 with one out in the second inning, but more damage was yet to come. After Harry Wright retired Pearsall on a foul fly, the next six batters reached base before Creighton was retired “on the bound” to Hunt of the Mutuals in short right field, “who first missed it on the fly.”31

Down 10-2, the Eighteen came storming back in the third. Each batter crossed the plate to make the score 11-10 in their favor.

The lead changed hands again when the Nine came to bat in the third, with Pearce and Pearsall scoring before center fielder George Vanderlip, future secretary of the St. George Club, retired Whiting on an outfield bound.

The Eighteen tied the score at 12-12 in the fourth inning with a single run against Creighton, who was back pitching. Creighton’s play to retire Vanderlip at home plate drew particular notice in the New York Clipper account of the game.32

Regarding Creighton’s fellow defenders, the Clipper judged center fielder Waddell’s play to be poor and claimed Flanley (spelled “Flanly” in its account) never fielded better, for which he drew loud applause. A “beautiful fly catch” by Pennington was also noted.33

The Nine tallied 10 runs in their half of the fourth, with each batter scoring once and Creighton twice. The three outs were recorded on Pearce, Pearsall, and Flanley, with each “striking twice” at Burns’s offerings.34

Once again the Eighteen responded with a single run. The Nine tacked on another seven runs in their next turn at bat to take a 29-13 lead.

The game continued in this fashion for another three innings, with the Nine growing their lead each inning. Home runs were struck in the final few innings by Pearce, Flanley, and Creighton, with Pearce’s blow (his second of the day) so splendid that he reached home “almost before the ball was handled.”35

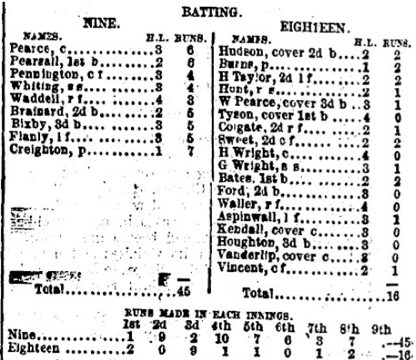

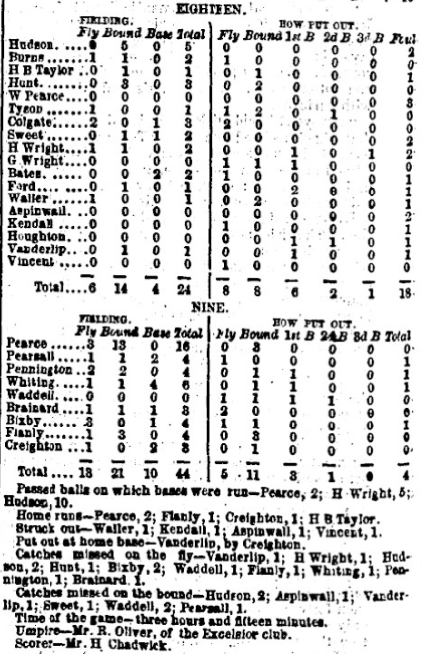

Darkness brought an end to the game after eight innings, with the Nine ahead, 45-16. The Brooklyn Eagle box score noted that 12 of the 16 runs compiled by the Eighteen “were made by the base ball players.”36

How much Harry Wright collected from his September 21 benefit was never published, but the fact that he was the game’s beneficiary had broader import than any money he might have received. Likely the first game in which he was openly compensated,37 it might also have been the first in which any base ball player was.38

Box score from the New York Clipper, September 28, 1861:

Acknowledgments

The author thanks SABR author Tom Gilbert for providing details on the playing career of Excelsior ballplayer A.T. Pearsall. This article was fact-checked by Stew Thornley and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Peter Morris, ed., Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company), 2013, Christopher Devine’s SABR biography of Harry Wright, John Thorn’s SABR biography of James Creighton and his Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011). The author also reviewed accounts of cricket matches, baseball games, and benefits of many kinds published between 1853 and 1861 in the New York Clipper, New York Times, Brooklyn Eagle, and New York Herald. He also examined the Baseball-Reference.com website for pertinent material on those players whose careers extended to the advent of the National Association in 1871.

Notes

1 The Clipper in this period also highlighted charitable benefits held for those who had suffered or might suffer great personal loss, such as a New York concert on May 25, 1861, to benefit a Volunteer Fund that assisted Union soldiers, and multiple events in Philadelphia to raise funds for the families of seven ballet dancers killed in a theater fire in that city. “City Summary,” New York Clipper, May 25, 1861: 46; “General Summary,” New York Clipper, September 28, 1861: 190.

2 “Benefit performance,” Britannica website, https://www.britannica.com/art/benefit-performance, accessed June 28, 2023.

3 See, for example, “Mike Henry’s Benefit,” New York Clipper, December 8, 1860: 266, “Johnny Monaghan’s Benefit,” New York Clipper, February 23, 1861: 356, or “Give Him a Good One,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1860: 282.

4 “Racket Tournament,” New York Clipper, October 6, 1860: 200.

5 For example, in 1860, a collection of cricketers from various New York clubs played a benefit in East New York for a professional cricketer, Sams, said to be “in very poor circumstances,” and a match was held at St. George Cricket Club Grounds in New York to benefit all U.S. cricket professionals. “Great Match at East New York,” New York Clipper, October 20, 1860: 213; “Matches to Come,” New York Clipper, June 23, 1860: 77.

6 Two weeks later, the Clipper described the benefit for Sam and Harry as an annual event. The author was unable to find evidence of a similar benefit for the Wrights in earlier years. “Cricket – Americans, versus Englishmen,” New York Dispatch, September 7, 1861: 9; “Benefit of the Veteran Cricketers,” New York Clipper, September 21, 1861: 178.

7 Paul Preston, Esq, “Reminiscences of a Man About Town,” New York Clipper, October 17, 1868: 220.

8 Just one week before Harry was so recognized, a Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, ignited the Civil War. “The Cricket Season in New York,” New York Clipper, April 20, 1861: 4.

9 An earlier announcement in the Brooklyn Eagle invited ballplayers interested in competing to provide their names to Harry Wright at the St. George Cricket grounds in Hoboken by the 18th. One stipulation spelled out by the Brooklyn Eagle was that no professional cricketers would play for the team of 11. “Out-Door Sports,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 19, 1861: 2; “Cricket,” New York Times, September 20, 1961: 5; “Cricket,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 13, 1861: 3.

10 It was common practice at that time to allow weaker teams to play with 18 as a handicap. The even more generous use of 22 players in this match followed a practice reportedly first adopted three years earlier by a Canadian cricket club. “Eleven First Class vs. Eighteen Second Class Players of the Toronto Club,” New York Clipper, September 4, 1858: 157.

11 “Grand Cricket Match,” New York Atlas, September 15, 1861: 8.

12 “Out-Door Sports.”

13 “Base Ball – To Players,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 13, 1860: 2.

14 The author has not identified any previous reports of a base ball game played for the benefit of an individual player, based upon his review of New York Clipper archives dating back to May 1853, the Craig B. Waff games tabulation and database of nineteenth-century baseball clippings at protoball.org, and nationwide newspaper archives housed at newspapers.com and genealogybank.com.

15 For example, in his Baseball in the Garden of Eden, MLB historian John Thorn shares reports of Creighton and possibly other Excelsiors receiving payments in 1860 and posits that “emoluments,” financial benefits for top players, may have induced Louis Wadsworth, the man he credits with baseball’s nine innings, nine players framework, to join the Knickerbockers in 1854. John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 51.

16 Baseball in the Garden of Eden, 120 and 123; “Base Ball,” Spirit of the Times, March 19, 1859: 66.

17 “Eleven English vs Twenty-Two Americans,” New York Clipper, September 28, 1861: 186.

18 With most able-bodied men gone to fight, it was rare for a New York area baseball club to muster enough players for a match between April and July in 1861. In a July 11 newspaper account that began, “War is down upon everything,” the Star Club was said to have only two of its first nine at home. Once the 13th Regiment of the New York State Militia, which included many ballplayers in its ranks, returned home from Maryland in late July, match play picked up considerably; but not for the Excelsiors, who remained dormant. “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Evening Star, July 11, 1861: 2; “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Evening Star, August 1, 1861: 2; “Return of the 13th Regiment,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 30, 1861: 2.

19 John’s brothers Frank and Charles had also played for the Excelsiors, but it was John who was an ardent cricket player. One year earlier, John, along with Creighton and Brainard, first took up cricket and, together with Henry Chadwick, Harry Wright, and other ballplayers of note, formed the American Cricket Club, a club for US citizens with a goal of “Americanizing” (speeding up) the pace of cricket matches. “An American Cricket Club,” New York Clipper, September 15, 1860: 170; “Cricket,” Brooklyn Evening Star, September 13, 1860: 2.

20 “Cricket in 1861,” New York Clipper, November 30, 1861: 259.

21 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers,” New York Clipper, September 28, 1861: 186. In addition to those clubs listed here, the New York Times game summary identified the Jefferson, Atlantic, and Knickerbocker clubs as providing players to the Eighteen. The author elected to adopt the list published by the New York Clipper, as that article listed the club affiliation for all but one of the Eighteen by name. The Brooklyn Eagle account of the game claimed that the team of Eighteen consisted of 10 cricketers and 8 base ball players, implying that they counted Harry Wright as a cricketer. “Cricket and Base Ball,” New York Times, September 22, 1861: 8; “Nine Ball Players vs. Eighteen Cricketers,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 1861: 3.

22 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

23 “Cricket and Base Ball,” New York Times, September 22, 1861: 8.

24 “Nine Base Ball Players vs. Eighteen Cricketers,” Brooklyn Evening Star, September 20, 1861: 3.

25 There was another local ballplayer named Waddell in 1861, listed in some box scores as Weddell, a pitcher for the Brooklyn Enterprise club. That Waddell appeared in a box score for a game played in Brooklyn on the 21st, ruling him out as being the Waddell who played in the Harry Wright benefit game. “Enterprise vs. Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 1861: 3. The New York Times game account agrees with the author’s list of teams represented in the Nine’s lineup with the exception of the Stars, which the Times omitted. The Brooklyn Eagle claimed only players from the Excelsiors and Atlantics populated the Nine, which clearly was not the case. “Cricket and Base Ball,” New York Times, September 22, 1861: 8. “Nine Ball Players vs. Eighteen Cricketers,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 1861: 3; “The Star Club,” New York Clipper, December 14, 1861: 275; “The Star Grounds,” New York Clipper, December 14, 1861: 274.

26 “Nine Base Ball Players vs Eighteen Cricketers,” Brooklyn Eagle. Two members of the Eighteen, Harry Wright and an amateur, Waller, had faced Creighton in the reputed first shutout in baseball history, a game on November 8, 1860, in Hoboken between the champion Excelsiors and cricketers from the St. George Cricket Club. “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 10, 1860: 2; “Last Cricket Match of the Hoboken Season – Amateur Eleven vs. Professional Eleven,” New York Times, October 1, 1860: 8.

27 The New York Clipper cites Harry as catching, as did Henry Chadwick, in one of his scrapbooks, according to Christopher Devine’s Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Baseball. The New York Times, on the other hand, lists Harry playing second base, while the Brooklyn Eagle showed him as simply a fielder. The detailed play-by-play account in the Clipper, in contrast to summary reviews in the Times and Eagle, suggests that the Clipper more accurately portrayed where Harry, and for that matter all the players, were positioned on the field. Christopher Devine, Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2003), 23.

28 The box score published in the New York Clipper shows the youngster at shortstop, while the Brooklyn Eagle lists him at second base. The New York Times says he played in the field, but showed others manning each infield position. Christopher Devine, in Harry Wright, identifies George as having been “a second catcher” backing up Harry, based on an entry in one of Henry Chadwick’s scrapbooks. The author has adopted the positioning as defined in the Clipper for reasons detailed in an earlier note.

29 Pearsall is identified as a member of the Class of 1861 in the College of Physicians and Surgeons alumni catalogue, but he was one of 10 Class of 1861 members identified in the catalogue who did not appear in a New York Times list of new graduates who took the Hippocratic oath during commencement in March of 1861. Presumably Pearsall earned his degree in the fall of 1861. College of Physicians and Surgeons in the City of New York, Medical Department of Columbia College: Catalogue of the Alumni, Officers and Fellows, 1807-1891 (New York: Bradstreet Press, 1891), 85, https://archive.org/details/catalogueofalumn02colu/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater, accessed August 15, 2023; “College of Physicians and Surgeons,” New York Times, March 15, 1861: 8; Dr. Miraculous, “The Ex-Excelsior, Founding Father of Montgomery Baseball,” Dr. Miraculous blog site, September 17, 2014, http://drmiraculous.blogspot.com/2014/09/the-ex-excelsior-founding-father-of.html.

30 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

31 Hunt may have been Dick Hunt, who played for the Mutuals in 1866, though he would have been only 13 or 14 years old in September of 1861. “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

32 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

33 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

34 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

35 “Base Ball Players vs. Cricketers.”

36 “Nine Ball Players vs. Eighteen Cricketers,” Brooklyn Eagle.

37 This may have been the first benefit for Wright, but it wasn’t the first benefit in which he was involved. In the July 20, 1858, opener of the best-of-three New York vs. Brooklyn picked nine series at the Fashion Race Course in Queens County, New York, the little-known Wright played middle field (second base) and batted last for the New York side. The net proceeds from that game’s admission fees ($71.09) were donated to the “Widows and Orphans funds of the Fire Departments of the two cities.” “The Great Base Ball Match,” Brooklyn Times, July 21, 1858: 3; “Grand Base Ball Demonstration,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 10, 1858: 3; “The Sporting Season,” New York Atlas, August 1, 1858: 1.

38 In his Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Baseball, author Christopher Devine identifies an 1863 benefit held by the Knickerbocker club for Harry, his father, and two others (in which Harry netted $29.65), as being the first instance of Wright openly playing base ball for money, but he does acknowledge that this Nine vs. Eighteen game was also a benefit held for Wright. The benefit game to which Devine refers may in fact have been held three years later. Author David Quentin Voigt in American Baseball describes Harry Wright as earning a cash cut of $29.65 at an 1866 benefit. MLB historian John Thorn pointed out that rain limited the sporting contests held at that benefit, originally planned to include both cricket and baseball, to cricket alone. “The First Baseball Card, Arguably?” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/1844.20, accessed July 24, 2023.

Additional Stats

Nine 45

Eighteen 16

Elysian Fields

Hoboken, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.