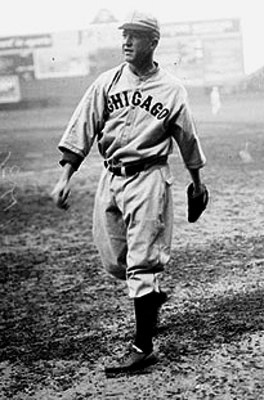

September 21, 1919: Cubs’ ‘Old Pete’ Alexander needs only 58 minutes for shutout

In 2017 a major-league game typically lasted more than three hours. Imagine completing one in less than one hour? That’s what the Chicago Cubs’ Grover Cleveland Alexander did when he needed just 58 minutes to shut out the Boston Braves on the north side of the Windy City. [Alexander] “figured the game was not worth wasting any time on,” sardonically quipped sportswriter James Crusinberry in the Chicago Tribune.1

In 2017 a major-league game typically lasted more than three hours. Imagine completing one in less than one hour? That’s what the Chicago Cubs’ Grover Cleveland Alexander did when he needed just 58 minutes to shut out the Boston Braves on the north side of the Windy City. [Alexander] “figured the game was not worth wasting any time on,” sardonically quipped sportswriter James Crusinberry in the Chicago Tribune.1

When players arrived at Weeghman Park for a Sunday afternoon game to conclude a three-game series, there was little incentive to play other than pride (and the offseason contract) as the season wound down. Skipper Fred Mitchell’s Cubs (72-60), in third place, 19½ games behind the front-running Cincinnati Reds, were making their season finale in the six-year-old steel and concrete ballpark, originally built for the Whales of the Federal League, to finish a 14-game homestand. The sixth-place Braves (54-78), whom manager George Stallings had guided to an unlikely World Series title five years earlier, had reached the end of a grueling 18-game road swing, and were playing on an opponent’s diamond for the 25th time in their last 28 contests. The Braves could be forgiven for looking forward to their Pullman sleeper coaches on their evening train ride back to the Hub, while the Cubs undoubtedly regretted leaving their homes and the friendly confines to travel to St. Louis and kick off a season-ending road trip.

The Cubs had been widely predicted to capture their second consecutive pennant in 1919, but their season had not unfolded as anticipated. One of the reasons for the disappointments was starting pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander. Once considered the best hurler in the NL, “Old Pete” had won 190 games in seven campaigns with the Philadelphia Phillies (1911-1917), but had made only three appearances for the Cubs in 1918 before he was called to duty and served on the front lines in the World War. His harrowing experiences in a field artillery unit had left him shellshocked, deaf in one ear from a shrapnel injury, and with a damaged right arm from firing howitzers. He also developed alcoholism and epilepsy. Not in baseball shape as the season started, Alexander struggled and missed four weeks with arm pain. Since his return on July 15, he had looked like hurler who had won 30 or more in three straight seasons and was victorious in 10 of his last 16 decisions with a 1.49 ERA to improve his slate to 14-11 (1.87). Toeing the rubber for the Beantown nine was right-hander Red Causey (13-6, 3.87 ERA), acquired along with three others on August 1 in a blockbuster trade with the New York Giants for southpaw Art Nehf.

A crowd of 5,000 braved the threatening, dark skies to take in the last Cubs game of the decade. The game emerged as a typical pitchers’ duel of the Deadball Era. The Braves squandered a scoring chance in the first when Charlie Pick reached on first baseman Fred Merkle’s error with one out and moved to third on Ray Powell’s single before Alexander retired the next two batters. The Cubs also threatened in the first when Charlie Hollocher belted a doubled against the wall in right with one out, followed by Buck Herzog’s walk, but could not push a run across.

Both the Tribune and Boston Herald noted that the players went about their business with alacrity, hurrying to and from their positions between innings, almost as if they were attempting to complete the game in record time.2 They also declared that it was Alexander’s goal to complete in a game in less than an hour. Cubs backstop Bill Killefer, opined Crusinberry, “gave the sign unusually fast and Alex tossed the ball up almost before the sign were given.”3

While Alexander escaped a triple by Walter Holke in the fourth, Causey had yielded only one hit until Old Pete came within “four feet” of blasting a home run, in the fifth.4 Powell fielded the carom off the wall in right field and held Alexander to a long single.

After the Braves squandered Tony Boeckel’s leadoff single in the sixth, the Cubs got on the board when Merkle reached on a surprise bunt and advanced to third on Turner Barber’s double. Up stepped Charlie Deal, whose two-run home run in the first game of the doubleheader the day before accounted for all of the runs in the Cubs’ victory. He lined a double to left-center field, driving in both runners.

Employing a bit of “trickery,” according to Crusinberry, the Cubs tacked on another run in the eighth.5 Facing Al Demaree, who had replaced Causey to start the frame, the Cubs loaded the bases on a walk by Hollocher and singles by Herzog and Merkle with no outs. After Barber fanned, Deal hit a short popup to the grass behind second base. Hollocher bluffed a dash home; when keystone sacker Charlie Pick took the bait and hesitated, Hollocher sprinted home, sliding across the plate as Pick’s throw sailed high.

Alexander continued heaving the ball over the plate in the ninth, daring the Braves to hit the orb. Powell led off with a double, but was stranded at third when Alexander retired Dixie Carroll to complete the shutout in 58 minutes.

The contest was remarkably swift even in an era when games averaged approximately 1 hour and 58 minutes to complete.6 Alexander finished with a six-hitter, fanned four and walked none while facing 33 batters. The Cubs collected nine hits. All told, 67 batters came to the plate; stated differently, a player stepped into the batter’s box every 52 seconds. On this same day, Sherry Smith of the Brooklyn Robins defeated the Cincinnati Reds, 3-1, in the Queen City in 55 minutes. One week later, on September 28, the New York Giants’ Jesse Barnes tossed a complete game against the Philadelphia Phillies in the Polo Grounds in just 51 minutes, in the fastest nine-inning game in major-league history, a record that will presumably never be broken. Remarkably, 70 batters came to the plate in that game; or once every 43.1 seconds, which is about the time between pitches in the contemporary game.

A week later, the 32-year-old Pete Alexander tossed his second consecutive shutout, 2-0, against the Reds to conclude his first full season with the Cubs since his blockbuster trade with a disappointing 16-11 record. However, he led the NL in ERA (1.72) for the fourth time and shutouts (9) for the sixth time. Alexander rebounded in 1920 to win an NL-best 27 games and once again paced the circuit in ERA (1.91), but struggled the rest of his career with alcoholism and the psychological effects of the war. He retired after the 1930 season with a career record of 373-208, including 90 shutouts.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 James Crusinberry, “Cubs Close the Season with Victory Over Braves, Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1919: 15.

2 “Alexander Wastes No Time by Trimming Tribe,” Boston Herald, September 22, 1919: 10.

3 Crusinberry.

4 “Alexander Wastes No Time by Trimming Tribe.”

5 Crusinberry.

6 Data about length of games for the 1919 season is not complete. The average for 1917 was 1:51; for 1920 1:51; between 1910 and 1933, the average length of games fluctuated between 1:51 and 1:59. See baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/misc.shtml.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 3

Boston Braves 0

Weeghman Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.