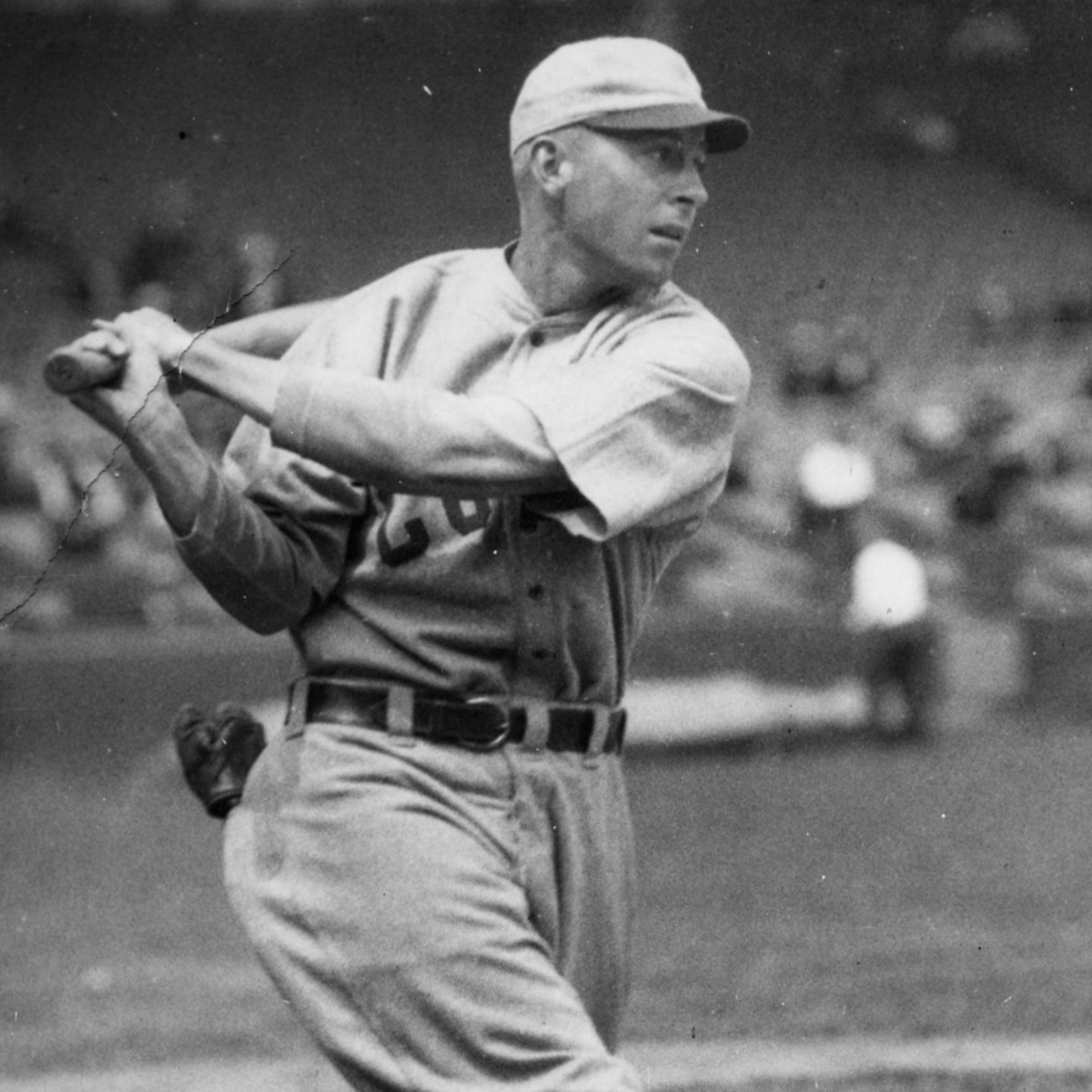

Charlie Hollocher

After his rookie season in 1918, Chicago Cubs shortstop Charlie Hollocher was hailed in some circles as the next Honus Wagner, one of the first five inductees in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was also mentioned in the same breath as another all-time great.

After his rookie season in 1918, Chicago Cubs shortstop Charlie Hollocher was hailed in some circles as the next Honus Wagner, one of the first five inductees in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was also mentioned in the same breath as another all-time great.

“For a time it seemed as though Rogers Hornsby, of the Cardinals, would win this honor [Wagner’s successor as the National League’s leading star], but of the two Hollocher seems designed for the greater career,” a New York Sun baseball critic predicted after Hollocher hit .316 and led the pennant-winning Cubs in four offensive categories.1

Six years later, however, mysterious stomach maladies caused Hollicher to retire from the game.

In 1940, he ended his life with a shotgun.

Charles Jacob Hollocher was born on June 11, 1896, in St. Louis, Missouri. He was the first child of Jacob and Annie (Engel) Hollocher. A younger brother, Louis Milton Hollocher (born in 1900), played eight years of minor-league baseball, rising as high as the Pacific Coast League. A second brother, Robert, was born in 1904.

Hollocher’s father, Jacob, was an insurance salesman. Annie did not work outside the house. The 1900 census shows the family living in Quincy, Illinois, a town along the Mississippi River about 120 miles north of St. Louis. Jacob was then working for the Sup Life Insurance Company. The family had moved back to St. Louis by 1910, with Jacob still working in insurance.

Charlie attended Central High School in St. Louis and played baseball there.2 As a youth, he honed his skills on the sandlots. His interest in baseball intensified in 1913 when he saw Wagner play with the Pittsburgh Pirates against the hometown Cardinals. “Hollocher, although only a youngster, was so taken up with the star’s actions that he decided then and there to become a shortstop, one of the best in the land,” according to a story in the Waterloo (Iowa) Evening Courier and Reporter five years later. The article quoted Hollocher: “Baseball was my pal. I played it from morning until night, and the following year my ambition was realized when I signed to play with the Alpen Braus in the Trolley League [in St. Louis].”3

The Trolley League, which was officially called the Missouri-Illinois League, was a semipro circuit with teams from St. Louis and the surrounding areas in Illinois.4 In 1910, the league had 10 entries, but clubs were added and left over the years. Many of St. Louis’s professional players gained experience in the league, which featured the best teams in St. Louis—except for the big-league franchises, the Cardinals and Browns. A local paper in 1908 compared the level of play to Class D minor league baseball.5

Hollocher played for the Trolley League’s Wabadas as well as the Alpen Braus. They were the class of the local teams. In June 1914, the lefty swinger had three hits including two doubles in the Alpen Braus’ 17-1 win against the Ben Millers.6

According to the Waterloo newspaper, Frank Boyle, the manager of the Keokuk (Iowa) Indians in the Class D Central Association, discovered the 19-year-old infielder in 1915.

However, author Arthur Ahrens provided an alternate story of how Hollocher came to the attention of the Keokuk club. “While playing for a local amateur team called the Wabadas, he caught the eye of sportswriter John B. Sheridan, who taught him the game’s finer points,” Ahrens wrote. “As the young Hollocher graduated from the amateur ranks to semiprofessional status, his friends urged both the Cardinals and Browns to give him a tryout, but the scouts of both teams declined, citing his alleged inability to hit.”7

The 5-foot-7, 154-pound Hollocher was indeed less than impressive at the plate for Keokuk, hitting .229 in 124 games, although his 99 hits included 14 doubles and four triples. However, “almost overnight, the youthful shortstop became the fielding sensation of the league.”8 The Indians finished in the second division that year after some of their wins were thrown out because they used more than four players who had played at least 30 days in a league of higher classification. As a result of financial difficulties, the franchise was sold to Fort Dodge, Iowa, ending 12 years of continuous baseball in the Gate City.

Frank Boyle was also instrumental in getting Hollocher to Portland in the Double-A Pacific Coast League for 1916. Toward the end of the 1915 campaign, Portland manager Judge McCredie asked a former major-league umpire working in the Central Association to find a good shortstop for him. Upon Boyle’s recommendation, the umpire urged McCredie to sign Hollocher rather than the Burlington shortstop, which McCredie did.9

In late October 1915, Hollocher continued his Trolley League action. He collected three hits in the Wabadas’ victory against a team that included Chicago White Sox catcher Ray Schalk in Litchfield, Illinois.10 Afterwards, “the players of both teams were guests of the mayor and citizens at a banquet in the evening,” a St. Louis newspaper reported.11

Hollocher was the youngest player on the Portland club in 1916, and he struggled, hitting just .190 in 14 games. Demoted to Class B Rock Island in the Three-I League, he showed more promise with a .289 batting average in 89 games. He also continued his stellar play in the field.

In 1917, Hollocher had a breakout season for Portland. He hit .276, collecting 224 hits in 813 at-bats, including 33 doubles and nine triples. He also scored 125 runs. With the glove, despite committing 62 errors, he made 495 putouts and had 686 assists at short. One of his teammates was Babe Pinelli, a major league umpire from 1935 to 1956. Pinelli was behind the plate for Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series.

A few months later, McCredie heaped lavish praise on his former infield star, calling Hollocher “the best shortstop I ever saw.”12 McCredie expanded: “He not only is the most wonderful fielder in the business, but he has baseball sense and baseball instinct. He’s doing things on the field right now that men like Wagner and Joe] Tinker were doing years after being in the big show.”13 The account also added this vivid description: “He plays close to the ground and just seems to skid over in front of hard hit balls. Many a time I’ve seen them hit out that way and figured he didn’t have a chance to get them, but he would slide over some way, come up with the ball, and snap it over to first without losing an instant.”14

Hollocher held out for more money after the Cubs purchased his contract before spring training began on the West Coast in 1918. Addressing the holdout, Cubs President Charles Weeghman said “that if ever a youngster breaking into the major leagues was treated fairly in the matter of salary, it is this young man Hollocher.”15 In addition, Weeghman claimed that Hollocher’s contract “called for a bigger salary than ever before paid to a youngster graduating from the minors.”16 The president then sounded a cautionary note: “Very few clubs made money last year and very few will show profits this [year], but we owners are going right ahead, paying the same salaries, and all this in the face of adverse conditions.”17

As for reports that Hollocher was demanding a $5,000 contract, a Portland newspaper in March 1918 concluded: “It is not known what salary the Cubs offered Hollocher, but it is a safe bet that Charlie is not asking $5,000 or anywhere near that figure.”18 By March 20, however, Hollocher had signed a contract and was “fielding in the same old brilliant style and dispatches from the training camp at Pasadena, California, say he is hitting the ball hard and often,” according to a Waterloo report.19

By July, Hollocher had impressed his manager, Fred Mitchell, among others. “I think Hollocher today is a better shortstop than Walter [Rabbit] Maranville. His arm is just as good, he covers as much or more ground than the Rabbit, and he is hitting any and all kinds of pitching,” Mitchell said.20 By August, Hollocher had moved up to third in the National League batting race with a .314 average.

With the Armistice still about five months away, World War I was on the minds of players and fans alike throughout the season. A Portland newspaper reported in August that Hollocher’s draft board had not given him permission to enlist in the Navy, meaning that he would play with the Cubs until the season was over. The Cubs’ biggest loss to the military that year was star pitcher Grover “Pete” Alexander, who appeared in only three games in 1918.

The Cubs clinched the 1918 NL pennant on August 24 with a doubleheader sweep over the Brooklyn Robins at Weeghman Park, the forerunner to Cubs Park and Wrigley Field. The Cubs finished 84-45, 10½ games ahead of the second-place New York Giants. Their pitching staff had a league best 2.18 ERA, and Hollocher led the circuit in games played (131), plate appearances (588), at-bats (509), hits (161), singles (130), and total bases (202).

The World Series against the Boston Red Sox started on September 5 in Chicago. Looking ahead, Hugh Fullerton, the “celebrated dopester of baseball,” said Hollocher was better than Boston’s veteran shortstop, Everett Scott.21 “He [Hollocher] has gone through the season without a single slump, either in batting or fielding,” Fullerton added. “He has made errors [53], plenty of them, but that may be attributed largely to the fact that he goes after balls that other fielders would not attempt to head off.”22 Fullerton concluded that although Boston pitchers Babe Ruth, Sam Jones, and Carl Mays might give Hollocher trouble, “there is every reason to believe that the young Chicago star will hit against the Boston hurlers.”23

The Red Sox took two of the first three games, which were played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park because of its greater seating capacity. The clubs split the next two games at Boston’s Fenway Park as left-hander Jim “Hippo” Vaughn tossed a five-hit shutout for the Cubs in Game Five. The Bruins lost Game Six, 2–1, and thus the series went to Boston — although the game almost wasn’t played because players objected to all first-division teams receiving a share of World Series revenue for the first time.24 Like most of the other Cubs, Hollocher didn’t fare well against Rex Sox pitching, hitting just .190 in 21 at-bats.

Noting that Hollocher had filled a five-year void left by Tinker, the 1919 Spalding Base Ball Guide said, “No young shortstop in recent years, in his first season with a major league club, has done so much to steady it and to assist it both on the field and at bat as this boy did in 1918. Only one other shortstop in the National League covered as much ground and only two others in the position were to be considered as ranking with him. These were Art] Fletcher of New York and Dave] Bancroft of Philadelphia.”25

A Fort Wayne, Indiana, newspaper called Hollocher the “most brilliant player to come into the major leagues in a decade” upon announcing that he had signed his contract for the 1919 season.26 Highlights that season included a 6-for-8 performance in a doubleheader loss to the Boston Braves on August 26. His hits included two doubles and a triple. However, Hollocher’s batting average fell to .270 for the year, and the Cubs slipped to third place.

A barnstorming trip with teammate Bill Killefer ensued. After it ended, Hollocher married his high school sweetheart, Jane Ellen Gray, on October 6, 1919, in St. Louis.

That winter, chewing gum magnate William Wrigley Jr. became the holder of the largest voting block of Cubs stock (in 1921, he assumed complete control of the franchise).27

The Cubs’ downtrend continued in 1920 — the team finished in a fifth-place tie and manager Mitchell was fired at the end of the season. Hollocher played in only 80 games that year as the result of an appendicitis operation on July 30. However, he did hit .319, getting 96 hits in 301 at-bats.

During the off-season, he was the subject of trade rumors. In November 1920 Cubs officials “vigorously denied” that a trade was imminent involving Hollocher, Alexander and a couple of unnamed players for Cincinnati’s Heinie Groh, Dutch Ruether, Earle “Greasy” Neale, and Larry Kopf.28 “We wouldn’t trade Alexander and Hollocher for the whole Cincinnati team,” Cubs secretary Johnny Seys said.29

By then 25 years old, Hollocher returned to full-time duty the next season. In 140 games, he hit .289, with 161 hits in 558 at-bats. However, the Cubs slid to seventh place and manager Johnny Evers of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance fame was replaced by Killefer in mid-season. Hollocher led the league’s shortstops with a .963 fielding average while handling 803 chances and making 30 errors. A game on September 3, 1921, in Cincinnati typified the season for both Hollocher and the Cubs. “He [Hollocher] covered a world of ground and took several chances without a sign of a wobble,” a Cincinnati newspaper reported. “Charlie also hit well, getting two of the four hostile hits.”30 Nonetheless, the Cubs lost, 4–0.

Hollocher had a career year in 1922, and the Cubs finished above .500 for the first time in four seasons at 80–74. August was an especially productive month for him. On August 13, he hit three triples in a 16–5 win over the St. Louis Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park. On August 25, he went 3-for-5 and drove in six runs in a record-setting 26–23 win over the Philadelphia Phillies at Cubs Park. Chicago scored 10 unearned runs in the second inning and 14 more runs in the fourth inning for a 25–6 lead at that point. The previous record for the most runs in a game (44) was set in a Players League game on July 12, 1890, when the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders beat the Buffalo Bisons, 28–16.

On August 29, again in St. Louis, Hollocher scored four runs in a game. When the season ended, he had amassed 201 hits, 90 runs, 37 doubles, eight triples, 69 RBIs, and a .340 batting average in 152 games. He also set a club record when he struck out only five times in 592 at-bats, third best all-time. Once again, he led the league’s shortstops in fielding with a .965 average.

Hollocher’s descent into baseball oblivion started before the next season opened. He was later quoted as follows: “My health first broke when at Catalina Island [off the California coast] in the spring of 1923. I returned to St. Louis for an examination by Dr. Robert F. Hyland, who examined me and then turned me over to a specialist.” It’s not certain when exactly he gave this account, which appeared in his obituary in The Sporting News on August 22, 1940.

The quote continued, “They advised me that I would ruin my health if I played ball that season. But Bill Killefer, the manager of the Cubs, came to St. Louis and urged me to join the team, telling me that I didn’t have to play when I didn’t feel well. I yielded to Bill, and, once in uniform, couldn’t stay on the bench. I played when I should have been home.”31

Despite playing in just 66 games in 1923, Hollocher had a career-high .342 batting average. Yet despite his status as the Cubs’ captain, he left the team on August 3 without notifying the front office. Teammates and fans wondered if he’d played his last game. However, before departing for his home in St. Louis, he left a note for Killefer that said: “Tried to see you at the clubhouse this afternoon but guess I missed you. Feeling pretty rotten so made up my mind to go home and take a rest and forget baseball for the rest of the year. No hard feelings, just didn’t feel like playing anymore. Good luck.”32

Hollocher then asked Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis to be put on the voluntarily retired list for the rest of the season. On August 11, Landis absolved the Cubs’ star despite the latter’s desertion.33

Hollocher was the subject of trade rumors again over the next winter. Stories appeared in several newspapers, including one in the Washington Court House (Ohio) Herald, that asked “Will Trade Cure Charlie Hollocher of Ills the Doctors Couldn’t Find?” An accompanying photo of him catching a ball was captioned, “Charlie Hollocher, star Cub infielder, is booked to play with the St. Louis Cardinals next season as a result of a trade recently hatched.”34 While the Cubs had spent lots of money on specialists the past two years to determine what ailed him, “the x-rays proved the suspect—trouble with his stomach—did not exist,” the caption added.35

Other newspapers speculated that month about a trade involving Hollocher and Hornsby, who had hit .384 in 1923. According to a story in the Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, “It is generally believed that these two stars will figure in one of the big deals due to be pulled this winter. The chances are good that neither will be with his present team.” That report added, “Hollocher, who lives in St. Louis, has hopes of playing there or at least leaving Chicago.”36 (The Cubs eventually did acquire Hornsby from the Boston Braves in November 1928 for five players and $200,000, long after Hollocher had left the game for good.)

Despite reports that Hollocher was gaining weight and would report for spring training in 1924, he missed the preseason workouts at the Cubs’ site on Catalina Island. On May 20, Chicago Tribune sportswriter Irving Vaughan wrote, “The X-ray plates of Charlie Hollocher’s stomach have definitely determined that there is nothing organically wrong with the star shortstop.”37

In his second at-bat during his final season, he bounced a home run through a grating under the grandstand and finished 3-for-4 against the Giants at Cubs Park. By August 20, however, his batting averaged had dipped to .245. On September 4, manager Killefer said he had allowed Hollocher to go home for health reasons. His last appearance on a baseball diamond came on October 3, 1924, when he played the last two innings of a City Series game against the White Sox. He went hitless in his only at-bat and the Cubs lost, 6-3.

Thereafter, his only other experience with major league baseball was as a scout for the Cubs in 1931. After retirement, he operated a tavern in Richmond Heights, Missouri. He was also an investigator for the county prosecuting attorney and a watchman at a drive-in movie theater.

His life started unraveling again when his wife — Jane Ellen Hollocher of Des Peres, Missouri — filed for divorce and custody of their 16-year-old daughter in Clayton, Missouri, in early March 1939, charging “general indignities.”38 According to the divorce petition, the Hollochers separated on February 28, 1939. A St. Louis County court granted the divorce on March 17, 1939, and awarded Jane Hollocher $20 a month alimony and an added $20 to support their daughter.39 Shortly afterward, Charlie married Ruth Fleming.

Hollocher’s life ended prematurely on August 14, 1940. His body, with a bullet wound in the neck, was found lying beside his parked automobile just south of Litzsinger Road near Lindbergh Boulevard in St. Louis. According to Constable Arthur Mosley, a new shotgun, which Hollocher had purchased from a mail order store the previous day, was under the ballplayer’s arm. Sunglasses and a membership card in the Association of Professional Baseball Players were found near Hollocher’s body.40 A note on the car’s dashboard said: “Call WALnut 4123. Mrs. Ruth Hollocher.”41 A funeral was held on the morning of August 16 at the Edith E. Ambruster Chapel on Lindell Boulevard in St. Louis.42 A private burial was held afterward at Oak Hill Cemetery in Kirkwood, Missouri.43

His second wife told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that the stomach ailment that forced him to retire from baseball at age 28 had been bothering him for the past three or four months before his death.44 Apparently, Hollocher’s early retirement from the game caught people off guard. “He appeared healthy and robust and his friends were amazed over his retirement from baseball as he was only 27 [sic] at the time,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported the day after his death.45

What was the true nature of Hollocher’s ailment? “Whether his sickness was something unknown to medical science of that era or largely psychosomatic will probably never be known,” author Ahrens concluded. “Equally, one can only speculate on the great career that might have been.”46

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to SABR members Brian Flaspohler of St. Louis and Shane Etter of Keokuk, Iowa, for their assistance.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com; Baseball-Almanac.com, Retrosheet.org; and clippings from Hollocher’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. Also helpful were newspaperarchive.com, paperofrecord.com, and wikipedia.org.

Notes

1 “Charlie Hollocher Continues To Win Praise,” The (Portland) Sunday Oregonian, September 1, 1918, 2.

2 In 1984, the school was converted into a performing arts school with about 400 ninth through 12th grade students.

3 “Sight of Honus Wagner Prompted Charlie Hollocher to Become Baseball Player,” Waterloo (Iowa) Evening Courier and Reporter, May 2, 1918, 12.

4 Email from SABR member Brian Flaspohler, August 21, 2020.

5 Flaspohler email.

6 “Wabadas Continue Fast Ball in Trolley League,” St. Louis Globe -Democrat, June 29, 1914, 10.

7 Arthur Ahrens, “The Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher,” http://research.sabr.org/journals/the-tragic-saga-of-charlie-hollocher (http://research.sabr.org/journals/the-tragic-saga-of-charlie-hollocher), accessed March 21, 2020).

8 “Chicago Scribes Amuse F. Boyle.”

9 “Chicago Scribes Amuse F. Boyle,” Waterloo Evening Courier and Reporter, above.

10 “Wabadas beat Litchfield, 5-2,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 25, 1915, 10.

11 “Wabadas beat Litchfield, 5-2.”

12 “Is Best In Business,” Moline (Illinois) Daily Dispatch, January 22, 1918, 9.

13 “Is Best in Business.”

14 “Is Best in Business.”

15 Charles Weeghman, “Cubs Hollocher Is a Holdout,” Chicago Examiner, February 24, 1918, Part 3, 3.

16 Weeghman, “Cubs Hollocher is a Holdout.”

17 Weeghman, “Cubs Hollocher is a Holdout.”

18 “Fans Think Hollocher Story Is Camouflage,” The (Portland) Morning Oregonian, March 15, 1918, 18.

19 “Diamond Dust,” Waterloo Evening Courier and Reporter, March 20, 1918, 12.

20 “Hollocher One Reason Why Cubs Win, Says Pilot,” Waterloo Evening Courier and Reporter, July 4, 1918, 6.

21 “Dopester Figures Hollocher Better Than Boston Star,” Waterloo Evening Courier and Reporter, September 2, 1918, 6.

22 “Dopestar Figures Hollocher Better Than Boston Star.”

23 “Dopestar Figures Hollocher Better Than Boston Star.”

24Les Krantz, Wrigley Field: The Centennial: 100 years at the friendly confines (Chicago: Triumph Books LLC, 2013), 25.

25 “The National League Season of 1918,” 1919 Spalding Base Ball Guide, https://archive.org/details/spaldingsbasebal19191chic/page/n103/mode/2up), accessed June 28, 2020.

26 “Hollocher Signs With Cubs For 1919,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Journal-Gazette, March 9, 1919, 10.

27 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999), 175.

28 “Cub Officials Deny Trade,” Hammond (Indiana) Lake County Times, November 23, 1920, 8.

29 “Cub Officials Deny Trade.”

30 “Gossip of the Game,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, September 4, 1921, 6.

31 Charles J. Hollocher, The Sporting News.

32 Ahrens, “The Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher.”

33 Ahrens, “The Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher.”

34 “Will Trade Cure Charlie Hollocher of Ills the Doctors Couldn’t Find?” Washington Court House (Ohio) Herald, November 28, 1923, 7.

35 “Will Trade Cure Charlie Hollocher of Ills the Doctors Couldn’t Find?”

36 “Hornsby and Hollocher to Figure In Big Deal of the Winter Season,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, November 6, 1923.

37 Ahrens, “The Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher.”

38 Unidentified article dated March 9, 1939, Hollocher file, Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Library.

39 Unidentified article dated March 23, 1939, Hollocher file, Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Library.

40 “C.J. Hollocher Takes Own Life,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 15, 1940, 5.

41 “Former Baseball Player Kills Self,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 14, 1940, 1.

42 “Charlie Hollocher’s Funeral Tomorrow,” St. Louis Star and Times, August 15, 1940, 15.

43Charles Jacob Hollocher, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7472260/charles-jacob-hollocher (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7472260/charles-jacob-hollocher), accessed August 28, 2020.

44 “Former Baseball Player Kills Self,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, above.

45 “C.J. Hollocher Takes Own Life,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, above.

46 Ahrens, “The Tragic Saga of Charlie Hollocher.”

Full Name

Charles Jacob Hollocher

Born

June 11, 1896 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

August 14, 1940 at Frontenac, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.