September 21, 1963: Pirates’ Gene Baker becomes first African-American to manage in the major leagues

Thanks in no small part to Bruce Markusen’s 2009 work, The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates, even non-Pirates aficionados are now familiar with the story of how, at Three Rivers Stadium on September 1 of that year Danny Murtaugh filled out a lineup that featured, for the first time in major-league history, a starting nine made up exclusively of African-Americans and Latinos.1 Certainly, as Markusen and others have noted, this was not done purposefully so as to break down racial and ethnic barriers in the sport; rather, the “Whistling Irishman” merely went with what he considered to be his best players for that specific contest against the Philadelphia Phillies: It resulted in a 10-7 victory for the home club.

Thanks in no small part to Bruce Markusen’s 2009 work, The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates, even non-Pirates aficionados are now familiar with the story of how, at Three Rivers Stadium on September 1 of that year Danny Murtaugh filled out a lineup that featured, for the first time in major-league history, a starting nine made up exclusively of African-Americans and Latinos.1 Certainly, as Markusen and others have noted, this was not done purposefully so as to break down racial and ethnic barriers in the sport; rather, the “Whistling Irishman” merely went with what he considered to be his best players for that specific contest against the Philadelphia Phillies: It resulted in a 10-7 victory for the home club.

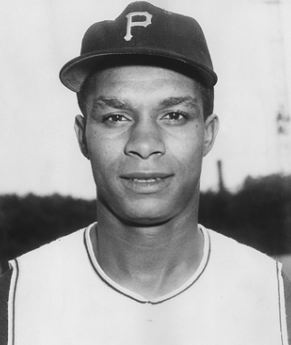

What many may not be aware of is that approximately 10 years before, the Pirates were involved in another racial milestone: the first time an African-American would manage a team at the major-league level. This momentous yet mostly overlooked event took place at Dodger Stadium on September 21, 1963, when both Murtaugh and coach Frank Oceak were tossed from the game by umpire Doug Harvey for arguing a close call at first base. Into the managerial breach now entered former Kansas City Monarchs, Chicago Cubs, and Pirates infielder (and at that time Pirates coach) Gene Baker.

Although he guided the squad for but two innings, Baker made history and helped to pave the way for Frank Robinson to become the first African-American major-league manager in 1975 with the Cleveland Indians.

Gene Baker was involved in many “firsts” during his career on the diamond. He was the first African-American signed by the Chicago Cubs, in 1950. He played his first season in the minors in his home state of Iowa (in Des Moines), hit .321, and scored 50 runs in just 49 games. He was one of the first African-Americans to play in the Pacific Coast League, where he spent most of 1951 through 1953 with the Triple-A Los Angeles Angels. Over those years he hit .278, .260, and .284. His final campaign was punctuated by 20 home runs, his professional best. Given his success in the PCL, many in Chicago wondered why the club did not bring Baker up to replace the Cubs’ regular shortstop during these years, Roy Smalley, who hit for considerably less average and power. Baker finally got his chance with the big club in the latter stages of the 1953 season. He was called up on August 31, but due to a back injury, he did not make his first appearance until September 20. By then Ernie Banks had already taken the field at shortstop for the North Siders. Club management decided to shift Baker to second and he and Banks formed a more-than-reliable double-play combination. Both players were named to the 1954 Sporting News rookie team. At the plate, Baker did not disappoint either, hitting .275, .268, and .258 over his time in the Windy City. He was a 1955 All-Star. Given that he was 32 after the 1957 campaign, the Cubs felt they could move him to another club; that turned out to be the Pirates, an organization that would employ Baker for the rest of his career.

As a Pirate starting in 1957, he backed up Bill Mazeroski and Dick Groat and played in 111 games. He was slotted as Pittsburgh’s third baseman for 1958, but suffered a severe leg injury on July 13 and was lost for the rest of that season, as well as for 1959. Baker returned to the field in 1960, but in a utility role. He played sparingly during the regular season, and went hitless in three at-bats during the World Series against the New York Yankees. With the start of 1961, his role became even more restricted, and the Pirates waived him on June 15. Less than a week later, Baker was named manager of the Pirates’ Class-D Batavia, New York, affiliate. With this announcement, the Pirates had broken a significant barrier: naming the first African-American to skipper a major-league-affiliated squad. Given the tenor and assumptions of many during these times, it was necessary for Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown to reassure fans that Baker was “capable” of handling the job. “He is a fine gentleman with outstanding baseball knowledge and experience. We’re confident he will do a fine job in the managerial field,” Brown said. His confidence was well placed, as Baker guided his team, which was in seventh place when he took over, to a third-place finish in the standings, as well as a victory in the first round of New York-Penn League playoffs. As a result, Baker earned a promotion in 1962 to the Pirates’ Triple-A team in Columbus, and then to the big-league club for 1963. It was late in that season that certain events transpired and resulted in cementing Baker’s status as a pioneer in the sport.2

After having played their final home game on September 18 against the Cubs, the Pirates took off to finish the season on a nine-game Western swing through Los Angeles, Houston, and San Francisco. The first game of the set against the Dodgers took place on September 20 and resulted in a 2-0 defeat for Pittsburgh, leaving the team at 72-82, 23 games behind LA. The next day’s matchup featured a pitching duel between Bob Friend and Sandy Koufax. As usual, a large crowd of over 48,000 witnessed the proceedings at Chavez Ravine. Both hurlers were sharp from the outset and there was no scoring over the first three innings. In the Pirates’ half of the fourth, Donn Clendenon homered off Koufax for the game’s first tally. Friend continued his mastery over the first-place Dodgers through six frames. Pittsburgh scored again in the top of the seventh as, after a Clendenon flyout to deep center, Ted Savage singled and stole second as Mazeroski struck out, then scored on a single by Bill Virdon to make the score 2-0 for the visitors. In the bottom of the frame the Dodgers scored twice to tie the game on singles by Jim Gilliam and Wally Moon, a groundout by Tommy Davis, a single by Ron Fairly (which scored Gilliam), then a single by Willie Davis off Harvey Haddix (who had replaced Friend). Johnny Roseboro grounded into a double play to end the rally.

In the top of the eighth, the Pirates regained the lead with singles by Clemente, Clendenon, and Savage. Mazeroski was then walked intentionally and Ron Perranoski replaced Koufax on the hill. The final out of the inning came when Bill Virdon grounded out, pitcher to first. Both Murtaugh and Oceak contested the call and were ejected. This left Gene Baker in charge of the Pirates for the final two frames. Of course, it would have been wonderful if there had been a victory to discuss after all of these significant events. It was not to be as Willie Davis hit a three-run home run in the bottom of the ninth off Tommie Sisk after singles by Tommy Davis and Ron Fairly,to win the game for Los Angeles.

While Gene Baker did not get “credit” in the won-lost column for his managerial effort in this contest, it was an important breakthrough. An African-American had managed in the majors and had demonstrated the ability to lead, if but temporarily, a team at this level. In 1964, Baker was once again assigned to lead the Batavia squad. This season did not turn out as well as did 1961, however. This team finished dead last in the circuit with a mark of 33-97. After that year, Baker and the Pirates parted ways in regard to managing, though he remained in the team’s employ for the next 23 years. He returned to his hometown of Davenport, Iowa, and served as the Pirates’ chief scout in the Midwest. Gene Baker died on December 1, 1999, from a heart attack. While he did not gain great notoriety from his exploits, he proved to the management of baseball that a man of his race was more than capable of leading men on the diamond. As his widow noted after Baker’s passing: “He was very proud of some of the accomplishments that he made with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was a black man in a white man’s sport, and he did very well in that sport.”3

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used information from retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Bruce Markusen, The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates (Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2009).

2 Robert J. Puerzer, “Gene Baker: Unsung Hero in the Integration of Major League Baseball,” Black Ball, Volume 4, Number 1, Spring 2011: 28-37.

3 Elizabeth Bloom, “Pittsburgh Pirates’ Gene Baker Quietly Crossed Baseball’s Color Lines,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 7, 2016. See: post-gazette.com/sports/pirates/2016/02/07/As-a-Pirate-Gene-Baker-quietly-broke-baseball-s-color-barriers/stories/201602070090.

Additional Stats

Los Angeles Dodgers 5

Pittsburgh Pirates 3

Dodger Stadium

Los Angeles, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.