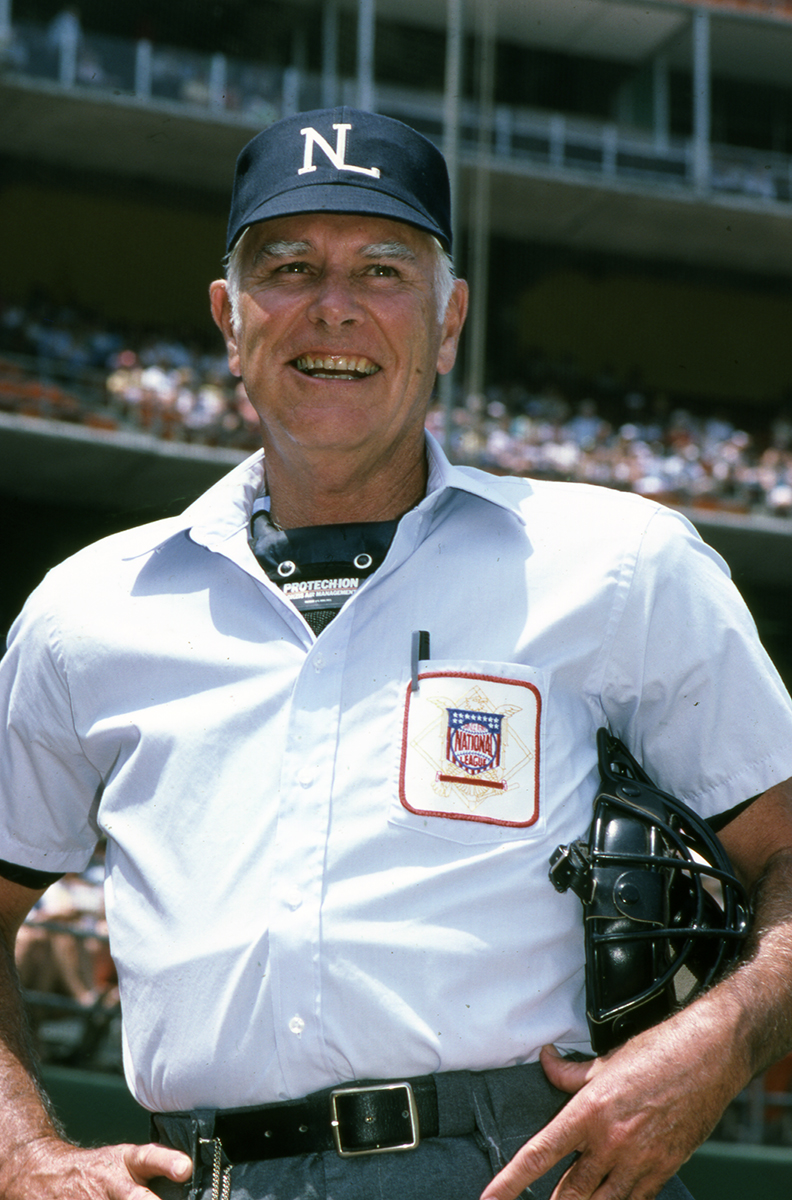

Doug Harvey

“The integrity of the game is the umpires. Nobody else. The entire integrity of the game is the umpires.” — Doug Harvey1

It was the late 1980s. The Cincinnati Reds had replaced the Big Red Machine with the Nasty Boys, and the Nastiest of the Nasty Boys was Rob Dibble. In the beginning of his career, Dibble had a habit of tapping his glove against his leg as he stood on the rubber. One day, the umpire was Doug Harvey. Harvey stepped out from behind home plate and strode to the mound. “Young man,” he said, “the next time you do that, I will call a balk.” Twenty-five years later, Dibble recalled his first meeting with God, and remembered Harvey as the pre-eminent umpire of his day, with an abundance of talent and patience.2

It was the late 1980s. The Cincinnati Reds had replaced the Big Red Machine with the Nasty Boys, and the Nastiest of the Nasty Boys was Rob Dibble. In the beginning of his career, Dibble had a habit of tapping his glove against his leg as he stood on the rubber. One day, the umpire was Doug Harvey. Harvey stepped out from behind home plate and strode to the mound. “Young man,” he said, “the next time you do that, I will call a balk.” Twenty-five years later, Dibble recalled his first meeting with God, and remembered Harvey as the pre-eminent umpire of his day, with an abundance of talent and patience.2

Harvey himself wrote: “I knew I wanted to be an umpire when I was six years old. My dad was an umpire — and a damn fine one — and I wanted to be just like him. I wanted nothing more than to be out on that field, and I umpired in the major leagues for thirty-one wonderful years, and for that I’m very grateful.”3

Harold Douglas Harvey was the third of four sons, and he was born in South Gate, a suburb of Los Angeles, on March 13, 1930. His father, Harold W. Harvey, who had migrated from the Midwest to California at a young age, worked in trucking for the Union Ice Company, and the family lived in South Gate. Doug’s mother, born Margaret Teters in Oklahoma, was from mixed Cherokee and Choctaw breeding. She worked as a waitress and then took a position as cashier at the local Safeway supermarket. At an early age, the future umpire was called Doug, so as not to be confused with his father. At the age of 4, Doug was afflicted with nephritis, a kidney infection, and it took him almost two years to get well and regain his strength. When Doug was 10, his father took another trucking job, and the family moved to El Centro, 170 miles away on the border with Mexico. During World War II, Harold Harvey was the civilian personnel director of the Camp Lockett Army Base.

In El Centro, Harold umpired industrial league and high-school games when he wasn’t working at Camp Lockett. After the war, he got a job selling tickets for the El Centro Imperials of the Class-C Sunset League, on occasion working as a stand-in umpire, getting a good reputation that didn’t hurt Doug when he, still in high school, began umpiring semipro and Industrial League baseball games. In school Doug played all sports, was on the California state championship basketball team as a junior, and went on to attend El Centro Junior College. While in college he married Joan Manning, and shortly thereafter left school. He worked at several low-paying jobs and his marriage, which produced a son, Douglas Lee Harvey, ended in divorce within two years.

Harvey was able to get a partial scholarship to San Diego State. He hit well enough in college (.378) to receive offers to play professional baseball, but he refused, wanting to stay close to home to attend to his sick mother and see his infant son as much as possible. A broken leg playing football ended his collegiate athletic career and, short of funds, he dropped out of college.

By 1956 Harvey’s life was going nowhere. He was working odd jobs and umpiring amateur and semipro baseball whenever the opportunity presented itself. He decided to try to get a job as a professional umpire. He wrote letters but was getting no place when he got his first break. He umpired a game for the Southern California Baseball Championship. A Milwaukee Braves scout at the game, Johnny Moore, liked what he saw and put in a good word for Harvey. Not long after, he had a job in the Class-C California League for $250 a month.

Alimony and child support were such that Harvey had little in the way of funds and could not afford to go to umpiring school. Nevertheless, he set out to make himself the best umpire he could be. He committed himself not only to being authoritative and fair on the field but also to learning the rulebook cover to cover. He was a no-nonsense fellow for whom name-calling was totally out of bounds and the cause for a quick ejection.

During his second year in the California League, Harvey met Joy Ann Glascock, a college student who was working at the ballpark in Bakersfield. It wasn’t long before the two became engaged. On September 24, 1960, a year after Joy graduated from college, they were married.4 They remained married for more than a half-century.

In early 1961 Harvey got a job umpiring in the Arizona Instructional League. Once again, as was the case five years earlier, his style and acumen caught the eye of someone in a position to push him forward. This time it was 82-year-old Clarence Henry “Pants” Rowland, a former major-league manager, scout, American League umpire, and former president of the Pacific Coast League. On Rowland’s recommendation, PCL President Dewey Soriano hired Harvey to work in the Pacific Coast League, a jump from Class C to Triple-A.5

After the season, National League President Warren Giles secured a job for him as an umpire in the Puerto Rico Winter League. Harvey was highly regarded by league President Pedro Vasquez, and was hired to work in the National League, starting in 1962. He was assigned to Al Barlick’s crew, joining Shag Crawford and Ed Vargo. Barlick and Harvey did not initially get along. Harvey discovered that Barlick was unhappy when Harvey was chosen over umpire Billy Williams, a Barlick favorite, to be promoted. Over the years, Barlick grew to appreciate Harvey’s skills as an umpire.

His first game was on April 10, 1962, and it was the first time his father got to see him umpire professionally. Harvey, who was umpiring at third base that day, said, “It was as big a thrill for him as it was for me.”6

Harvey set his own standards for positioning himself, calling a game, and talking with managers and players. He saw arguments as part of the game, and when there was a close call he fully expected to have a “discussion” with a complaining manager. As long as the discussion was civil and there was no name-calling, he would let the player or manager have his say.

It wasn’t long before the 32-year-old arbiter ejected his first player. On May 9 the temperature was 38 degrees and the Pirates were playing the Braves at County Stadium in Milwaukee. Harvey was stationed at second base. With the game tied 1-1 in the third, the Braves took the lead on singles by Joe Torre, Frank Bolling, and Roy McMillan. Torre, trying to advance from first to third on McMillan’s hit, was not far past second base when catcher Smoky Burgess grabbed left fielder Bob Skinner’s throw and gunned down Torre as he tried to get back to second base. Torre disputed the call and his choice of words was deemed inappropriate by the rookie umpire.7

Thirty years later, in 1992, Torre was managing St. Louis. Harvey was in his final season and thought it would be appropriate for Torre, who had been his first ejection, to be his last. And on September 16, the time was right. (Both teams had been virtually eliminated from playoff contention.) Torre came out of the Cardinal dugout to “contest” a call, as pre-arranged (the cover story was that Torre questioned whether pinch-hitter Craig Wilson had been properly announced into the game), and Harvey gave him the heave-ho in the top of the ninth inning.8

One of Harvey’s earliest memories as a major-league umpire came from a game he was umpiring between St. Louis and the Dodgers on May 11, 1962. In the second inning, Dodgers pitcher Stan Williams had two strikes on the Cardinals batter, and the count was 1-and-2. The next pitch was coming straight for the plate, and Harvey prematurely called “strike three.” At the last instant the pitch broke out of the strike zone. The batter quietly walked away and over his shoulder calmly said, “Young fella, I don’t know what league you came from, but home plate is 17 inches wide, same as it is here. If you want to stay up here, wait until the ball crosses the plate before you call it.”9 The batter was Stan Musial, and the lesson was learned by the rookie umpire.

Toward the end of the 1962 season, Doug and Joy became parents for the first time when their son Scott was born. Harvey was umpiring in Pittsburgh and did not see his son until the baby was two weeks old. They later had another son, Todd.

What was Doug Harvey’s worst day behind the plate? In 1988, 25 years after the fact, he told writer Jerome Holtzman about a game in Houston. In those days, the Colt .45’s, as they were then called, were playing in a ballpark notorious for its heat and mosquitoes. Most games were played at night and “the lights were like flashlights.” He was tired that evening, having been on the road for 10 weeks, and had a child at home who was terribly ill. He “couldn’t tell if it was a ball or strike.” He “vowed that I would never let it happen again, and I haven’t.”10

In 1964 Harvey was transferred to Jocko Conlan’s crew, and was teamed with Conlan, Tony Venzon, and Lee Weyer. When Conlan retired at the end of the season, he joined Shag Crawford’s crew. He was on Crawford’s crew for 12 seasons. During that first season, he was teamed with Crawford, Venzon, and Al Forman. Years later, Harvey said that Crawford was the best umpire he had worked with.11

Money wasn’t good for umpires in the 1960s when Harvey was promoted to the National League. His salary during those first two years was $8,000 per year. To supplement his income, he became a basketball referee. He was a referee during the inaugural season of the American Basketball Association in 1967.

Harvey also was a strong force in the umpires union, which was formed in 1963, his second year in the league, and over the years fought hard to improve benefits for umpires. Umpires struck during the first games of the 1970 playoffs, and in 1979 they stayed on the sidelines during spring training, looking for better pay. Asked to comment about the replacement umpires, Harvey said, “It’s like not having a police force in our society. The amateurs can’t cope because they don’t have our training.”12 In 1984 the umpires stayed out for the first games of the playoffs before Commissioner Peter Ueberroth agreed to arbitrate the matter. Harvey was part of a four-man crew that, as part of the agreement, umpired the final game of the playoff between the Cubs and the Padres and agreed to be available for the World Series.13

In his time in the National League, Harvey called many historic games and interacted with the greats of the game. On August 22, 1965, with the Dodgers playing the Giants in San Francisco, Harvey was at third base. Juan Marichal led off for the Giants in the third inning. There had been unusually bad feelings between the two teams and Marichal had been pitching the Dodgers batters a bit close. On each of the first two pitches to Marichal, Dodgers catcher John Roseboro stepped behind Marichal when firing the ball back to the pitcher, blazing the ball past Marichal’s ear. Marichal, enraged, hit Roseboro over the head with his bat. A brawl ensued with Harvey’s crew chief, Crawford, the home-plate umpire, at the bottom of the pile. Harvey tried to play peacemaker, and locate his comrade. Crawford ejected Marichal.

Harvey’s first of five World Series was in 1968, when the Tigers defeated the Cardinals. He also worked six All-Star Games and nine League Championship Series.

As much a fan as an arbiter, Harvey was very much in the right place at the right time on September 30, 1972. He was umpiring at second base when the batter rifled a shot to left-center field for a double. The center fielder returned the ball to the infield. Harvey asked the shortstop for the ball, which he handed to the batter as he congratulated Roberto Clemente on his 3,000th hit.

In 1974 Harvey was named a crew chief. His first crew comprised Harry Wendelstedt, Nick Colosi, and Art Williams. Over time, he worked with two umpires, Paul Pryor and John McSherry, who had more seniority, but he was able to maintain camaraderie with them and with all the other umpires he worked with.

On July 14, 1978, Harvey ejected Dodgers pitcher Don Sutton after the umpires crew found three balls that were scuffed. Sutton was often accused of doctoring the ball.

On September 20, 1979, Harvey’s crew was umpiring a game in Philadelphia between the Pirates and Phillies. The teams had split two games and the Pirates needed a win to maintain their slim lead over Montreal in the NL Eastern Division. The game was tied going into the bottom of the sixth inning. With two runners on base, the Phillies’ Keith Moreland, in a play “that defines what it’s like to be an umpire,”14 lined a ball toward the left-field corner. Home-plate umpire Harvey’s view of the ball was blocked as the batter crossed in front of him. Third-base umpire Eric Gregg ruled the line drive had gone over the fence in fair territory, putting the Phillies up 4-1.

Bedlam erupted and Harvey was besieged by the angry Pirates. Gregg “looked like he was being attacked by wasps or yellow jackets, because back in those days the Pirates had those awful yellow-and-black uniforms,” Harvey later wrote. The umpiring crew of Harvey, Gregg, Andy Olsen, and Frank Pulli got together and reversed the call. None of them had gotten a good look. It was the Phillies’ turn to erupt, charging the field, led by manager Dallas Green and one of Harvey’s favorite players, Mike Schmidt. Harvey ejected Green, the Phillies protested the game, and Moreland struck out. In the next inning, the Phillies scored a run and won the game, 2-1, dropping the Pirates to second place. In retrospect, Harvey said that the play was “the closest I’ve ever come to being stumped.”15

Harvey was never one to put up with nonsense. The Phillies were playing the Cubs at Wrigley Field in 1982 and Philadelphia reliever Ed Farmer was wild. Farmer had already walked two batters in the seventh and the count was 2-and-0 on a potential third baserunner when manager Pat Corrales removed him from the game. The departing Farmer hurled some expletives in Harvey’s direction and was ejected, causing Corrales to exclaim, “How do you throw a guy out of the ballgame when he is already out?”16

Occasionally an umpire’s call can change the outcome of a game, and on June 6, 1984, Harvey was umpiring at third base in a game between the Mets and the Pirates. With the score tied 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth inning and Pirates center fielder Lee Mazzilli on third base, Jason Thompson launched a fly ball to center fielder Mookie Wilson. Mazzilli tagged up and scored what appeared to be the winning run. The Mets appealed the play, saying that Mazzilli left too early. Harvey, sure that it was the right call, ruled in favor of the Mets, and New York went on to win the game 2-1 in 13 innings. Harvey said, “That’s a call that if there’s any doubt in the umpire’s mind, he won’t make it. A call like that comes from the heart and guts.”17

How did Harvey get to be known as “God”? One story has it that San Diego catcher Terry Kennedy had seen Harvey checking out a rain-soaked field during a rain delay and made a comment about “God’s” walking on water. Another story has Whitey Herzog exclaiming, during an argument, “Who do you think you are — God?”18

Kennedy remembered well the game in question. It was May 28, 1984, and the Padres were in New York for a series against the Mets. Before the first game, Mets GM Frank Cashen asked Harvey to do everything within his power to get in the first game of the series as even worse weather was forecast for the next two days.

Kennedy recalled, “Doug was behind the plate, and I asked him how long we were going to play in such bad conditions. He said we had to make this game official or we would be playing back-to-back doubleheaders. (When the Padres next visited New York, the teams played two doubleheaders in a row. Had the May 28 game been rained out, there would have been three doubleheaders.) After the game, I was asked about playing in those conditions (the teams completed nine innings with the Padres winning, 5-4) and I made a comment about how the Son of God knew more bad weather was coming and we should play through this. (There was one 63-minute delay in the fourth inning.)19 It all started from that. Doug got wind of my comment and, instead of being insulted, he was actually pleased by it.” Kennedy went on to say, “Doug was a good umpire and kept his skills even as he got older, which was rare. He too enjoyed being in the rarefied air of major-league baseball.”20

By the time Harvey worked the National League Championship Series in 1986, use of the term was very widespread and even more respectful. As Jerome Holtzman noted in an article that year, “Many players and managers refer to Harvey as ‘God,’ because in 22 years in the National League he has yet to make a wrong call.”21

In the NLCS, the New York Mets were facing the Houston Astros and having all sorts of trouble with the offerings of Mike Scott. As had been the case with Don Sutton, Scott was accused of doing a little slicing and dicing of the ball. Umpire Harvey was the crew chief and drew the Game One assignment behind home plate. Scott, the National League’s most dominant pitcher that year, was so strongly believed by the Mets to be putting something extra and quite illegal on the ball that backup catcher Ed Hearn’s sole task was to track down balls and look for evidence of scuffing. In the first inning Gary Carter swung at strike two and asked Harvey to check the ball. Harvey examined the ball, and tossed it back to Scott. Carter struck out on the next pitch. Harvey elaborated: “Carter said, ‘Harvey, Harvey, no way. Look at that ball.’ So I looked at it. I purposely turned toward Carter. I turned it over one way, then the other. That ball was clean. The man just exploded two extraordinary pitches.”22

Carter, in his book A Dream Season, said of Harvey: “He’s tall with thick white hair and a face as stern as rock. He’s one of the premier umpires, and he is never wrong. I mean he knows everything. A pitch will come in, a ball, and Harvey will say, ‘That one missed by half an inch.’ Half an inch? What eyes! He tries to be helpful. He’ll study your stance, your swing, and say, ‘You know, son, you’re not holding your hands back enough.’ He calls every ballplayer son.”23

Mets catcher Ed Hearn said he was behind the plate one time when a pitch came in relatively low. Hearn thought it to be in the strike zone. Harvey called, “Ball!” Hearn questioned the call. Hearn had turned his glove fingers down to make the catch. Harvey said, “Look, son, you turn your hand down and it’s never a strike.”24

Harvey’s last season was 1992 and he retired as the most respected umpire in the game. He had stated that his goal was to work 5,000 games and retire at age 65. However, his knees were giving him problems and, at 62, he informed National League President Bill White that he was unable to continue. After the All-Star Game, it was announced that he would retire at the end of the season. When he umpired his last game, in October 1992, it brought his count to 4,673 regular-season games, which at the time was the third most for a major-league umpire.

In all of his years of umpiring, Harvey never was involved in a no-hitter. The closest he ever came was in 1969.

In his retirement, Harvey encountered medical issues. After chewing tobacco much of his life, he was diagnosed with throat cancer in August 1997. Radiation therapy proved successful and at the end of his treatment, he committed himself toward educating young people on the dangers of chewing tobacco.

In 2010, Harvey became the ninth umpire inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. By then, his mobility was limited as he had suffered a couple of strokes. It was thought for a time that he would not be able to attend the induction ceremony, but he was able to go to Cooperstown to accept induction, along with Andre Dawson and longtime nemesis Whitey Herzog. In his autobiography, published in 2014, he said he had regained his mobility, survived a bout with pneumonia, and was “hanging in there pretty good for an old guy who started out with twenty-two months in the hospital when I was four years old. I had to fight it then, and I’ve had to fight it all the way.”25

Reflecting on his time in the game, Harvey observed in 2015 that umpires were considered “necessary evils” when he broke in. Now they get a month off, and are allowed time off for things such as the birth of a child. With the use of replays, most confrontations are avoided.26

In 1986 manager Whitey Herzog of the Cardinals presented Harvey with a cap inscribed, “We’ll get along just fine as soon as you realize I’m God”27 — That’s basically it.

Harvey died at the age of 87 on January 13, 2018, in Visalia, California.

This biography is included in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and the following:

Books

Hearn, Ed, with Gene Frenette. Conquering Life’s Curves: Baseball, Battles, and Beyond (Indianapolis: Masters Press, 1996).

Kaiser, Ken, with David Fisher. Planet of the Umps: A Baseball Life From Behind the Mask (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003).

Skipper, John C. Umpires: Classic Baseball Stories from the Men Who Made the Calls (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 1997).

Articles

“Pittsburgh Second by a Half-Game: Phils Beat Pirates 2-1,” New York Times, September 21, 1979: A21.

Blair, Sam. “Seeking Solace Amid the Storm,” Dallas Morning News, July 25, 1978.

Coffey, Wayne. “Longtime Ump Harvey Says He Made the Right Call — Retirement,” New York Daily News, October 18, 1992.

Walfoort, Cleon. “Strikeouts and Men Left on Base are Making Braves’ Progress Slow,” Milwaukee Journal, May 10, 1962: 16-17.

Notes

1 Bruce Weber, As They See ’Em: A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires (New York: Scribner, 2009), 15.

2 Author interview with Rob Dibble, June 20, 2014.

3 Doug Harvey with Peter Golenbock, They Called Me God: The Best Umpire Who Ever Lived (New York: Gallery Books, 2014), 9.

4 Harvey, 67.

5 Harvey, 75.

6 Phil Collier, “Climb to Major Leagues Swift for Harvey, San Diego Umpire,” San Diego Union, May 27, 1962: B-11.

7 Harvey, 188; Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, May 10, 1962: 1D

8John Harper, “Cards Officially Eliminate the Mets,” New York Post, September 17, 1992: 67.

9 Harvey, 124.

10 Jerome Holtzman, “A Chat With God Offers Salvation,” Chicago Tribune, December 28, 1988: C1.

11 Author interview with Doug Harvey, March 15, 2015.

12 Jack Murphy, “Umpires See Anarchy Unless Pros Return,” San Diego Union, April 13, 1979: C-1.

13 Jerome Holtzman, “Umps End Strike, Go to Arbitration,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1984: C7.

14 Harvey, 229-233.

15 Ibid.

16 Jayson Stark, Philadelphia Inquirer, June 17, 1982.

17 Ken Rappoport (Associated Press), The Index-Journal (Greenwood, South, Carolina), June 7, 1984: 12.

18 Author interview with Bill Haller, June 18, 2015.

19 Murray Chass, New York Times, May 29, 1984: D15.

20 Letter to author from Terry Kennedy, June 2015.

21 Jerome Holtzman, Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1985: C3.

22 Bus Saidt, “Great Scott! Debate Over Scuffed Baseballs a Challenge to Game’s Integrity,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, October 14, 1986: B-1.

23 Gary Carter with John Hough Jr. A Dream Season (Orlando: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1987), 14.

24 Author interview with Ed Hearn, April 24, 2015.

25 Harvey, 268.

26 Author interview with Doug Harvey, March 15, 2015.

27 “A Chat With God.”

Full Name

Harold Douglas Harvey

Born

March 13, 1930 at South Gate, CA (US)

Died

January 13, 2018 at Visalia, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.