September 23, 1951: Murry Dickson wins 20th game for seventh-place Pirates

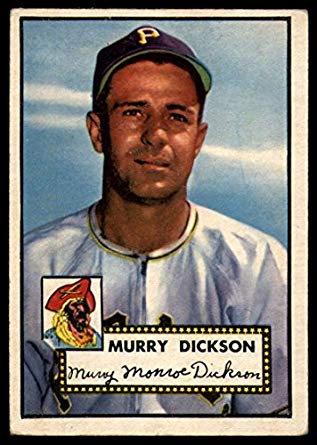

After competing for the 1948 National League pennant before finishing in fourth place, the Pittsburgh Pirates, on January 29, 1949, purchased right-hander Murry Dickson from the St. Louis Cardinals for $125,000 in an effort to improve their pitching staff for the 1949 season.

After competing for the 1948 National League pennant before finishing in fourth place, the Pittsburgh Pirates, on January 29, 1949, purchased right-hander Murry Dickson from the St. Louis Cardinals for $125,000 in an effort to improve their pitching staff for the 1949 season.

Regarded as one of the craftiest pitchers in baseball, Dickson had made his major-league debut with the Cardinals in 1939 at the age of 22, but didn’t become a permanent member of their staff until 1942. His best year with the Cardinals was in 1946, when he had a 15-6 record and started the seventh game of the 1946 World Series against the Boston Red Sox.

While the Cardinals won the deciding game, 4-3, on Enos Slaughter’s celebrated “mad dash” around the bases, Dickson was so angry about being taken out in the eighth inning with the Cardinals leading 3-1 that he dressed and left the ballpark. He drove around St Louis and listened to the rest of the game on his car radio.

Overcoming his unhappiness, Dickson became the workhorse of the Cardinals pitching staff for the next two seasons until he was sold to the Pirates. With the Pirates, Dickson continued in that role. In 1949, he pitched in 44 games, 24 of them in relief. In 1950, he pitched in 51 games, including 29 relief appearances.

Despite his reliability, Dickson hadn’t compiled a winning record since 1946, but all that changed in 1951. Used primarily as a starter, he won his first three games, including a 4-3 complete game against Don Newcombe and the Dodgers. By midseason, even with the Pirates floundering in the second division, he managed to stay at .500 or above. From July 15 through August 12, he won six games in a row to bring his record to 16-10 and on September 19 won his 19th game of the season, against the Boston Braves.

On September 23, Dickson, looking for his 20th win, started the first game of a doubleheader in Cincinnati. The Reds had struggled to score runs in 1951, but Dickson would still be facing a formidable lineup, led by sluggers Ted Kluszewski and Wally Post. He’d also have to beat Reds ace Ewell Blackwell in a matchup of pitching opposites.

Dickson, who stood 5-feet-10 and weighed 159 pounds, used a variety of pitches, including a knuckleball, and deceptive deliveries to get batters out. His former teammate Joe Garagiola claimed that players called him Thomas Edison because invented so many pitches.1 The Cubs’ Frankie Baumholtz hated facing Dickson: “His ball moved all the time and occasionally he’d sneak in a fastball. He was no fun to bat against.”2

Blackwell, who stood 6-feet-6 and weighed 195 pounds, was known as the Whip. The right-hander intimidated hitters with a side-arm fastball, once clocked at 99.8 mph. He knew his side-arm delivery “was intimidating and I took advantage of it. …. I was a mean pitcher.”3 He could tell Pirates slugger Ralph Kiner “was scared. … he’d bail out because my fast ball would break toward the batter.”4

After Blackwell retired the side in order in the top of the first, Dickson struck out leadoff hitter Bobby Adams on his way to a one-two-three inning. Blackwell had to pitch his way around an error and a single by Jack Merson in the second, while Dickson, after giving up two singles, struck out Roy McMillan and got Hobie Landrith on a ground ball to work his way out of trouble. Blackwell and Dickson gave up harmless singles in the third inning and retired the side in order in the fourth.

The Pirates finally broke through against Blackwell in the top of the fifth, but it was thanks to a costly throwing error by second baseman Adams. George Strickland doubled, then scored with two outs on Adams’s wild throw on a Pete Castiglione ground ball. With Castiglione on first, Blackwell walked George Metkovich, then gave up a run-scoring single to Gus Bell before striking out Kiner.

With a 2-0 lead, Dickson retired the Reds in order in the bottom of the fifth. After the Pirates failed to score in the top of the sixth, Adams led off the bottom of the inning with a single, then moved to third base on two groundouts. Kluszewski, however, flied out to right field to end the threat.

In the top of the seventh, Dickson, who would hit .273 for the season, singled and was sacrificed to second by Castiglione. After Metkovich lined out to third, Bell brought Dickson home with a single to right field to give the Pirates a 3-0 lead. When Dickson took the mound in the bottom of the seventh, he was nine outs away from a 20-win season with a Pirates team that was struggling to stay out of last place.

With one out, Dickson walked Grady Hatton, then gave up a two-out single to Landrith. With Blackwell due up, Reds manager Luke Sewell went with pinch-hitter Joe Adcock. Facing the tying run at the plate, Dickson bore down and struck out Adcock to end the inning.

After the Pirates wasted a Clyde McCullough single in the eighth off Reds righty reliever Frank Smith, Dickson had his finest inning in the bottom of the frame. Facing the top of the Reds lineup, he struck out Adams, Johnny Wyrostek, and Post. When he walked off the mound, he still possessed a 3-0 lead and was one inning away from his 20th win.

Dickson led off the top of the ninth with his second hit, but after Castiglione sacrificed, Jack Phillips and Bell failed to bring him home. In the bottom of the ninth, Kluszewski led off by lining out to short and Hank Edwards grounded out to second. When Hatton lofted a fly ball to center fielder Frank Thomas, Dickson became a 20-game winner for a team that would win only 64 games for the season and finish in seventh place, only two games ahead of the Chicago Cubs.

The irony of Dickson’s accomplishment in the 1951 season was that it was eclipsed by St. Louis Browns right-hander Ned Garver, who made history by becoming the first pitcher to win 20 games for a last-place team. His Browns finished the season with 102 losses and only 52 wins. Like Dickson, Garver was a craftsman on the mound. Satchel Paige once said that Garver knew more about pitching than anyone, except, of course, Paige himself.5

Unfortunately for Dickson, he would go on to pitch for a 1952 Pirates team, dubbed Branch Rickey’s “Rickey Dinks,” that set a modern Pirates record for ineptness with a record of 42-112. Dickson would make his own history by losing 21 games and becoming the first pitcher to have a 20-game-losing season after a 20-game-winning season.

After losing 19 games in 1953, Dickson was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies, where he lost 20 games in 1954. He bounced back in 1955 with a 12-11 record, and, after being sent to the Cardinals after a poor start in 1956, went on, at the age of 40, to win 13 games. After going 5-3 with the Cardinals in 1957, he ended his career as a part of the Kansas City-New York shuttle. With the Yankees, after spending most of the 1958 season with the A’s, he appeared in two games in the 1958 World Series. He ended his career with the A’s in 1959, just one year short of pitching in four decades.

Joe Garagiola was one of many teammates who admired Murry Dickson because of his intelligence and determination. He said that Dickson was “one of those guys who always wanted the ball and it was more than having a rubber arm. He was the kind of guy you wanted out there when things were tight.”6

Dick Schofield, who was Dickson’s teammate with the Cardinals in 1956 and 1957, remembered him as “a good guy … and a real battler, who threw every day on the sideline and wanted to pitch in every game.” Dickson’s roommate, Ken Boyer, told Schofield that Dickson’s regimen was to eat once a week and drink coffee all day long.7

While Dickson ended his career with a losing record at 172-181, his 172 wins were remarkable considering that he spent several seasons with awful baseball teams. Had he pitched for better teams, there is no doubt that he would have won over 200 games and earned a place in the Hall of Fame. But he had his moment of greatness in 1951 when he became a 20-game winner and, no doubt, inspired young pitchers Bob Friend and Vernon Law, who would go on to win 20 games for the Pirates and, in Law’s case, become a Cy Young Award winner.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, and Finoli, David, and Bill Ranier, eds. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia (New York: Sports Publishing, 2015).

Notes

1 Michael Gershman, David Pietrusza, and Matthew Silverman, eds., Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (Kingston, New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000), 287.

2 Daniel Peary, ed., We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 156.

3 Peary, 35.

4 Ibid.

5 Richard Peterson, ed., The St. Louis Baseball Reader (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 313.

6 Gershman et. al., 288.

7 Peary, 355.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 3

Cincinnati Reds 0

Game 1, DH

Crosley Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.