September 24, 1944: Homestead Grays repeat as Negro League World Series champions

“But coming down through that would heighten my sense because I could dig I would soon be standing in that line to get in, with my old man. But lines of all black people! Dressed up like they would for going to the game, in those bright lost summers. Full of noise and identification slapped greetings over and around folks. … [These were] legitimate black heroes. And we were intimate with them in a way and they were extensions of all of us, there, in a way that the Yankees and Dodgers and what not could never be!” — Amiri Baraka1

“But coming down through that would heighten my sense because I could dig I would soon be standing in that line to get in, with my old man. But lines of all black people! Dressed up like they would for going to the game, in those bright lost summers. Full of noise and identification slapped greetings over and around folks. … [These were] legitimate black heroes. And we were intimate with them in a way and they were extensions of all of us, there, in a way that the Yankees and Dodgers and what not could never be!” — Amiri Baraka1

The heart of U Street in North West Washington stretches from roughly 18th Street to 7th Street, bordered on each side by the corners of Florida Avenue as it’s cut off from its original identity as Boundary Road. It was here in the early years of the District’s history that the city ended and the rural highlands of DC began. And it was here, most visibly in the first half of the twentieth century, that DC’s black culture found its most iconic and accessible avenue. At its heart were the Howard Theatre on 7th, the Republic at 14th and U, and countless other movie houses and entertainment palaces.2 Culture could be found at every turn. Just to the north was a hub of jazz and classical music at Howard University and the Howard music department.3

And it was right there, where 7th met Georgia, that anyone interested in baseball would find themselves on any given summer day, the smell of the Wonder Bread factory several blocks away sweetening the air. Hopping off the Georgia Avenue streetcar, you had only a short walk to the gates of Griffith Stadium. Walking north, past Off Beat Confectionery, the Old Rose Social Club and District Novelty, you passed Little Harlem Café and the old billiard hall next to the Goodwill before turning right toward the gate, the sound of the stadium mingled with the excitement in the air.4 In 1944 the streets were vibrant, the wartime employment boom affecting all of DC, including the black community in and around U Street. Art Carter, a Howard University alumnus and a journalist with the Afro American, had partnered with Clark Griffith and was instrumental in promoting black baseball in DC to the African-American “elite” and middle-class culture, and Griffith Stadium had become the home for black sports fans in DC.5

Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis was, in September 1944, ill and would soon check himself into the hospital, never to check out. To some, his passing was the final death knell for the color barrier that had long segregated and poisoned the game since the late nineteenth century.6 Integration was on the horizon. But some of the sportswriters covering Negro League baseball were as worried about what integration might do to the Negro National League and Negro American League as they were eager to capitalize on the growing popularity of black baseball.7

In June of 1944 the news of D-Day had burst into headlines, and hope permeated a war-weary populace. Things were looking up. Those sentiments were shared by the Negro League team owners, who had listened to what Cum Posey and Wendell Smith had suggested during the 1943 World Series. After the chaos of 1943, three “Commissioners” had been appointed to oversee the 1944 Negro World Series between the Homestead Grays and Birmingham Black Barons: Frank Young of the Chicago Defender (who also ran the press box and served as official scorer); Sam Lacy, a writer for the Baltimore Afro-American; and Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier.8

Only one game of the 1944 Negro World Series was played in Washington. The first four games were played in Birmingham, New Orleans, and Pittsburgh. It kicked off on September 17 in Birmingham, where the Grays won, 8-3. They also won the next two games, in New Orleans and Birmingham (again). The Barons made a series of it on the 23rd in Pittsburgh, the Grays’ other home, with a decisive 6-0 victory, setting up a do-or-die game (for the Barons) in Washington on the 24th.9

The Grays had narrowly defeated the Barons in the 1943 Series, but the Birmingham squad had improved upon an already stellar roster for the ’44 season. Led by captain Tommy Sampson and All-Star shortstop Artie Wilson, the Barons eyed a triumph over the Grays until a late-season car accident removed Sampson, Pepper Bassett and Leandy Young from competition, and injured Wilson and Johnny Britton, who were able to play in the Series.10

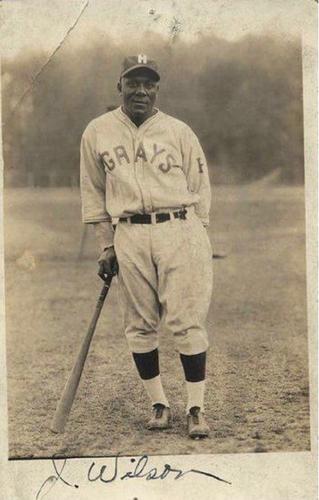

Returning for the Grays were most of the championship team of 1943, including a fully healthy Josh Gibson. Starting the game was Grays ace Roy Welmaker, just out of the Army, who took the mound in the bottom of the second with a comfortable 3-0 lead.11 It had all fallen into place quickly in the bottom of the first for the Grays. Jerry Benjamin and Sam Bankhead came out of the box swinging, each rewarded with a single. Thanks to a bobble by right fielder Ed Steele and a fielder’s choice, there was already one run home with just one out. Alfred Saylor, on the mound for the Barons, then intentionally walked Buck Leonard and Gibson and the crowd, estimated to be between 8,000 and 10,000, went wild as Jud Wilson dropped a single into shallow left to score Bankhead and Leonard.12

With the Grays up 3-0, the fans, some of whom were the “most passionate” fans of the Senators, were even more excited to see the Grays sweep the series.13

Welmaker pitched a masterful game, scattering hits here and there but walking no one. He faced few challenges until the fourth, when John Britton, playing in bandages since the car accident, reached on an error by Jud Wilson at the hot corner. Britton moved around the bases on another error by Wilson and a fielder’s choice, giving the Barons their first run. However, Welmaker was too sharp, and if the gloves behind him held, he would prove unbeatable.14

And just to prove it, in the bottom of the inning, Welmaker decided to take the run back that had been gifted to Birmingham in the top of the fourth. He ripped a double and one batter later was driven home by Bankhead’s sharp single. The score was now 4-1 Grays. Not only had Welmaker singlehandedly taken back control of the game, but had forced the hand of Barons manager Lucky Welsch to remove his dueling partner Saylor. Saylor’s replacement, Alonzo Boone, shut down the Grays’ vaunted offense.15

Only one more run was scored in the contest, by the Barons in the fifth. As if agreeing with Welmaker that the pitchers would control the fate of the game from both the mound and the plate, Boone reached first on an awkward infield bounce. He then advanced around the bases and scored on sloppy play, when Jesse Cannady, who had replaced Jud Wilson at third, committed an error on an easy grounder. Now that both pitchers had satisfied their urge to contribute runs, they both settled in and pitched scoreless ball for the rest of the game.16

That’s not to say there weren’t great moments for the fans. Despite an ailing wrist, Birmingham’s Artie Wilson fielded brilliantly. The Grays’ second baseman Jelly Jackson did as well, and the fans were treated to a base theft by Cool Papa Bell.17 But the hometown crowd was hungry for a Grays win, even if it meant the season would end with only one game played in Washington (though the fans would be treated to an exhibition game in the following days).18

The final out came on a double play on par with Tinker to Evers to Chance. With one out in the ninth and a runner on first, Johnny Markham hit a slow grounder to back to the mound. “Welmaker to Bankhead to Leonard.”19 Euphoria swelled on U Street as, for the final time, a Washington baseball team would claim a championship on District soil. The next time the Grays were in the Series, in 1948, when they once again faced a formidable Barons team, none of the games were played in Washington. It would not be until 2012 that a deciding postseason game was played in Washington.

About 50,000 saw all five Series games in 1944, proving the naysayers of the disorganized ’43 contest right — by appointing commissioners to ensure that all scheduled games, both official series games as well as exhibitions, were played when and where the fans expected them, the turnout was huge. According to Wendell Smith, there were more press requests for the 1944 Negro World Series than any previous major event, including the East-West games.20

Yet the end of the ’44 Negro World Series was also in some ways the end of an era of great black baseball. Landis died soon after the Series, and World War II ended within a year. Jackie Robinson played his first game in Montreal in April of ’46, and Josh Gibson died not too long after that. As many of the sportswriters of the day had feared, the integration of the National and American Leagues would spell the death of the Negro Leagues.

Notes

1 James Overmyer, Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1993), 63.

2 Blair A. Ruble, “Seventh Street: Black DC’s Musical Mecca,” in Maurice Jackson and Blair A. Ruble, eds., DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2018).

3 Lauren Sinclair, “No Church Without a Choir: Howard University and Jazz in Washington, DC,” in Maurice Jackson and Blair A. Ruble, eds., DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2018).

4 Boyd’s District of Columbia Directory, Vol. LXXXVI, 1944 Edition (Washington: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers 1944).

5 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2003).

6 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

7 Jim Reisler, Black Writers/Black Baseball: An Anthology of Articles from Black Sportswriters Who Covered the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1994).

8 “Grays Win ’44 World Series,” The Negro Baseball Yearbook: 1944 Yearbook, October 29, 1958: 10.

9 Fay Young, “Summary of 1944: Series Playoffs,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), September 30, 1944: 9.

10 “Grays Win ’44 World Series.”

11 Sam Lacy, “Grays Take 4 Out of 5 to Cop World Title: Barons Win but 1 Game in Title Playoff with Negro National League Champs,” Afro-American, September 30, 1944: 18.

12 Fay Young, “Grays Capture 4 Out of 5 to Win 1944 World Series,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), September 30, 1944: 9.

13 Snyder, 13.

14 Wendell Smith, “Grays Retain Baseball’s Top Banner,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 30, 1944: 12.

15 Fay Young, “Grays Capture 4 Out of 5 to Win 1944 World Series.”

16 Ibid.

17 Wendell Smith, “’Smitty’s’ Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 30, 1944: 12.

18 Fay Young, “Grays Capture 4 Out of 5 to Win 1944 World Series.”

19 Ibid.

20 Wendell Smith, “‘Smitty’s’ Sports Spurts.”

Additional Stats

Homestead Grays 4

Birmingham Black Barons 2

Game 5, Negro League WS

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.