September 26, 1912: Heinie Zimmerman won’t go home; Reds’ stalling efforts fail to catch Cubs

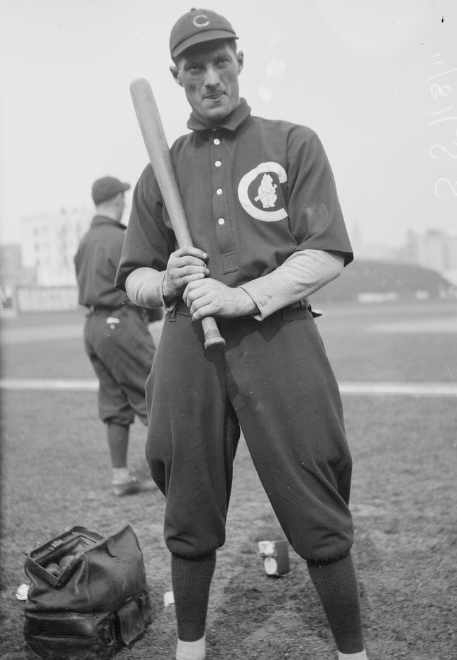

Mention the name Heinie Zimmerman to followers of baseball lore and they will more than likely think of one thing above all: the New York Giants third baseman’s futile pursuit of Eddie Collins down the third-base line in Game Six of the 1917 World Series.

Mention the name Heinie Zimmerman to followers of baseball lore and they will more than likely think of one thing above all: the New York Giants third baseman’s futile pursuit of Eddie Collins down the third-base line in Game Six of the 1917 World Series.

That’s the play in which Zimmerman’s Giants teammates botched a rundown and inexplicably left home plate uncovered. Their failure forced the slower Zimmerman to chase haplessly after the speedy Collins as the White Sox second baseman raced home to break a scoreless tie in the fourth inning. Chicago went on to a Series-clinching 4-2 win.1

Fairly or not, that debacle remains the one play most closely associated with Zimmerman’s name. It places him in the company of other players – Fred Merkle, Fred Snodgrass, Mickey Owen, Bill Buckner, and others – more famous for classic “boners” than for all of their other accomplishments on the diamond.

Note the headlines announcing Zimmerman’s death more than half a century later, in 1969: “Giants’ Heinie Zimmerman Dies; Committed 1917 Series ‘Boner’” (New York Times); “Henie Zimmerman, Famed for Goof, Dies,” (Philadelphia Daily News); “Bonehead Play Maker of 1917 Series, Dies” (Minneapolis Star Tribune); “Ex-Giant Goat in Chase Over Plate Dies, 82” (Boston Globe).

Five years before that Series game, Zimmerman, then with the Chicago Cubs, was in the news for a very different play at the plate, a play in which he – for a strategic reason – did everything he could to not reach home.

The story takes place on September 26, 1912, during the second game of a doubleheader between the Cubs and the Cincinnati Reds at Chicago’s West Side Park. The 25-year-old Zimmerman was nearing the end of what turned out to be the best season of his 13-campaign major-league career. He led the National League in many offensive categories, including batting average (.372), home runs (14), RBIs (104), hits (207), doubles (41), and slugging percentage (.571).

The first game of the September 26 doubleheader was strange enough. The Cubs led 9-0 going into the ninth inning, but the Reds scored 10 in the top of the ninth to take a 10-9 lead. It would have been the largest ninth inning come-from-behind win in major-league history – except that the Cubs scored two runs in the bottom of the ninth, without benefit of a hit to win 11-10. (Four walks and a hit batter produced the two runs.)

That set the stage for the nightcap, after an unusual intermission in which a group of theatrical performers in Arab dress “swarmed out on the field and played a game of association football in their bare feet,” using a baseball for the ball,2 hoping to entertain the crowd of 1,500 on what the Cincinnati Enquirer described as a “very cold” afternoon.3

The Cubs offense remained hot from the outset in the second game of the doubleheader. They scored two runs in the first, seven in the second, and one in the third, driving Cincinnati starter Rube Benton – who had allowed two inherited runners to score the tying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth in the opener – from the game. Leadoff hitter Jimmy Sheckard paced the Cubs’ attack with three runs scored; second-place hitter Ward Miller added two more runs. Meanwhile, Chicago’s starting pitcher, Larry Cheney, who “earned” the win in the first game despite walking three men with the bases loaded to give Cincinnati its short-lived lead, was holding the Reds scoreless.

Then things got really interesting.

There were, of course, no lights at Chicago’s West Side Park (or any other major-league ballpark) in those days. After a long first game and an especially long bottom of the second in the second game, there was some doubt that 4½ innings could be completed before darkness set in. If not, it would not be an official game and all records, including the Cubs’ 10-0 lead, would be wiped out.

The two teams did all they could to speed up (Cubs) or slow down (Reds) the game. Reds manager Hank O’Day “switched his men about with such careless abandon,” reported the Chicago Tribune, “that his batting order got all mixed up and at one stage of the game the umpires and captains had to appeal to the press to find out whose turn it was to hit.”4

The Cubs, in turn, wrote the Tribune’s Sam Weller, “attempted to rush matters by striking out in ridiculous fashion.”5 But nothing could top the antics that ensued during one of Zimmerman’s at-bats. Here’s how Weller described it:

“He went to bat intending to get out if possible on the first ball pitched in order to hurry matters, so he used only one hand in swinging the bat. He connected with the ball and drove it to left center for a three base hit, then when a bad throw got past the third baseman Heine [sic] trotted on up to the plate and stood one foot away until the pitcher had recovered the ball and thrown it to the catcher so he could be tagged out.”6

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer account of the game, “The Cincinnati players, just as anxious to stall off the five innings till dark, passed the ball around among themselves. But Umpire Cy Rigler forced them to tag Zimmerman out at the plate.”7

Rigler somehow managed to get the game past the 4½-inning mark, finally calling it after six innings with the Cubs still ahead 10-0, thus bringing to an end what has to be one of the strangest doubleheaders ever played.

The Tribune’s headline the next day? “Cubs Win Two in Comedy Matinee.”

The wins gave the Cubs a 1½-game lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates for second place in the National League, but Chicago was winless in its next six games – including two losses and a tie against the Reds and three losses against the Pirates – and Pittsburgh overtook Chicago for second. The Cubs finished the season in third with a 91-59 record; Cincinnati was fourth at 75-78-2.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN191209262.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1912/B09262CHN1912.htm

Notes

1 Frederick G. Lieb, “Zimmerman’s Shad, 2,803 Bones All in One, Makes Giants Easy Victims in Deciding Game of World’s Series: Giants’ Defeat Is Fourth in World’s Series,” New York Sun, October 16, 1917: 12.

2 Harry Daniel, “Cubs Take 2 Game from Reds; Latter Get 10 in 1 Round,” Chicago Inter Ocean, September 27, 1912: 4.

3 Jack Ryder, “Reds Make Record Rally but Drop First Contest Then Lose Second Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 27, 1912: 8.

4 Sam Weller, “Cubs Win Two in Comedy Matinee,” Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1912: 15.

5 Weller.

6 Weller.

7 Ryder, “Reds Make Record Rally but Drop First Contest Then Lose Second Game.”

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 10

Cincinnati Reds 0

6 innings

Game 2, DH

West Side Grounds

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.