September 7, 1889: The Candlelight Game

The September 7, 1889, game between the St. Louis Browns and the Brooklyn Bridegrooms is now remembered for the humorous episode when the Browns had lighted candles put up in front of their bench to emphasize to the umpire that it was too dark to play. But the game’s riotous ending and rancorous denouement fractured the American Association, and went a long way toward putting the organization on the road to extinction.

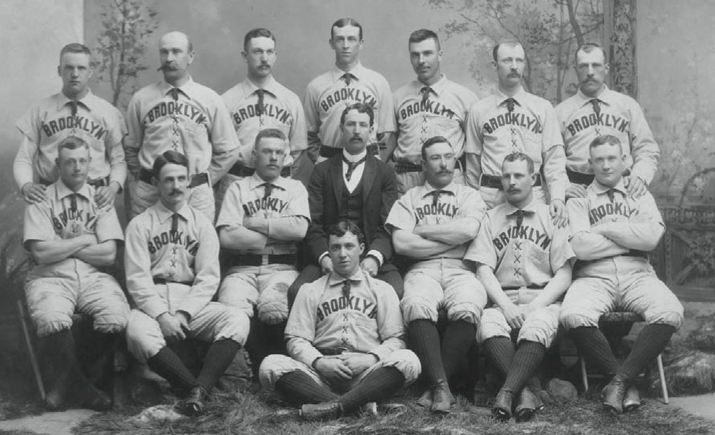

The Browns, led by Captain Charlie Comiskey and owner Chris Von der Ahe, were looking for their fifth consecutive pennant in 1889, and they led the race for most of the summer. Under the ownership of Charles Byrne, the Bridegrooms had gone to considerable expense to unseat the champs. Now finally in September of 1889, the Bridegrooms had moved into first place and led the Browns by 2½ games when the champs came to Brooklyn for a three-game series. But the future looked far from rosy for Byrne. On September 1, the Queens County sheriff had stopped the Bridegrooms game at Ridgewood Park, the venue the team had used since 1886 for lucrative Sunday games just beyond the city limits. State law prohibited Sunday amusements, but the authorities in Queens had allowed them to go on unmolested until now. Other Sunday games could be played while the case went through the courts, but there would be no law enforcement at the site in the meantime.

The Browns, led by Captain Charlie Comiskey and owner Chris Von der Ahe, were looking for their fifth consecutive pennant in 1889, and they led the race for most of the summer. Under the ownership of Charles Byrne, the Bridegrooms had gone to considerable expense to unseat the champs. Now finally in September of 1889, the Bridegrooms had moved into first place and led the Browns by 2½ games when the champs came to Brooklyn for a three-game series. But the future looked far from rosy for Byrne. On September 1, the Queens County sheriff had stopped the Bridegrooms game at Ridgewood Park, the venue the team had used since 1886 for lucrative Sunday games just beyond the city limits. State law prohibited Sunday amusements, but the authorities in Queens had allowed them to go on unmolested until now. Other Sunday games could be played while the case went through the courts, but there would be no law enforcement at the site in the meantime.

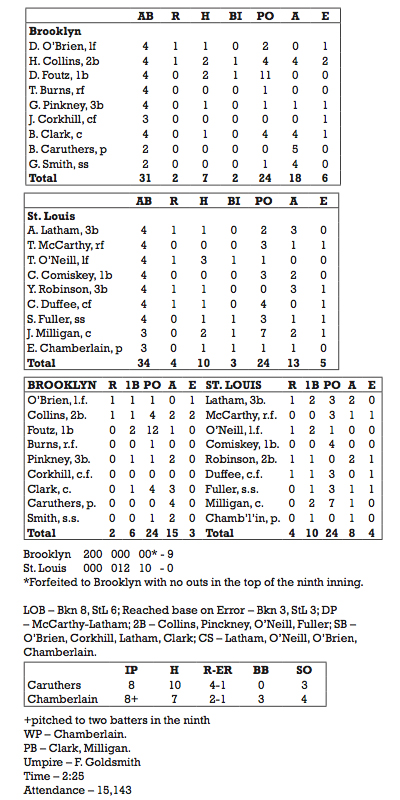

The big series opened on Saturday, September 7, with an immense crowd of more than 15,000 packed into Washington Park in downtown Brooklyn. The game they saw was quintessential American Association baseball, replete with brilliant fielding, desperate baserunning, and constant wrangling with the umpire. In the first five innings four men were caught stealing, three were tagged out at home, and two others were retired in rundowns between third and home.

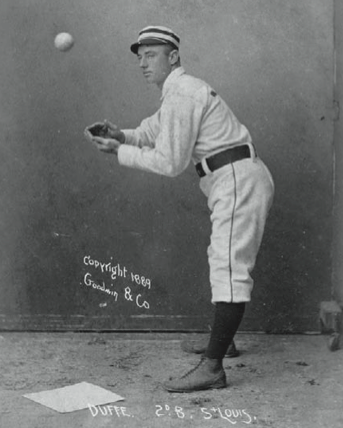

Fred Goldsmith, the old Chicago pitcher, was the arbiter, and he called “Play” at the usual 4 p.m. starting time under overcast skies. Brooklyn chose first bats and drew first blood, scoring two runs and giving Browns third baseman Arlie Latham a nasty spike wound in the process. St. Louis finally scored a run in the fifth. Charlie Duffee led off with a single to left and advanced to second when the return throw got away. Brooklyn put up a kick, claiming that Duffee had interfered with the throw. He then came around on an infield out and a scratch hit.

With the lead cut to 2–1 and the skies ominous, Brooklyn Captain Darby O’Brien urged Goldsmith to call the game, but the ump would have none of it. In the last of the sixth, the Browns grabbed the lead with a pair of runs, thanks to singles by Tip O’Neill and Yank Robinson and a double by Shorty Fuller, with a sacrifice and a wild throw added in. St. Louis comic Latham “turned flipflaps, stood on his hands and rolled over the ground in a perfect paroxysm of delight,”1 much to the amusement of the crowd.

Now it was Captain Comiskey’s turn to harangue for an end due to darkness. As the seventh inning began at around 5:40 p.m., there was some light left.2 But it seemed that every play caused an argument, and St. Louis delayed at every opportunity. Goldsmith assessed fines and threatened a forfeit to get the Browns back to their positions. St. Louis tallied another run in the seventh when O’Neill’s single brought in Latham. Before the start of the eighth inning, St. Louis right fielder Tommy McCarthy dunked the game ball in the water bucket to make it hard to hit. An enraged Goldsmith saw the trick and put a new ball into play. Meanwhile, Von der Ahe had sent an errand boy to a local grocery store for candles, and in the eighth inning he had them lighted and placed them by the visitors’ bench.

Now it was Captain Comiskey’s turn to harangue for an end due to darkness. As the seventh inning began at around 5:40 p.m., there was some light left.2 But it seemed that every play caused an argument, and St. Louis delayed at every opportunity. Goldsmith assessed fines and threatened a forfeit to get the Browns back to their positions. St. Louis tallied another run in the seventh when O’Neill’s single brought in Latham. Before the start of the eighth inning, St. Louis right fielder Tommy McCarthy dunked the game ball in the water bucket to make it hard to hit. An enraged Goldsmith saw the trick and put a new ball into play. Meanwhile, Von der Ahe had sent an errand boy to a local grocery store for candles, and in the eighth inning he had them lighted and placed them by the visitors’ bench.

The Browns’ “impudent exhibition of bulldozing” had made the crowd “like an excited mob,” and the fans “hooted and yelled and shouted like maniacs.”3 But despite Goldsmith’s indignation and injured sense of authority, by the time the ninth inning began it really was too dark to see. The first Brooklyn batter struck out but reached base when the catcher missed the ball. After another passed ball, the Browns refused to continue, leaving the field and heading for the clubhouse. A few of the players were hit by objects thrown by a frenzied portion of the crowd that followed them. Goldsmith, after waiting the required five minutes, declared the game a forfeit victory for Brooklyn.

Fearing further violence and knowing there would be no police presence on Sunday, Von der Ahe refused to have his team appear at Ridgewood the following day, again forfeiting. Rain prevented the final game of the series. The fine for forfeiting a game was $1,500, and the penalty for purposely failing to appear was expulsion from the Association. After a tortuous 10-hour meeting on September 23, the Association board of directors handed down a compromise verdict: The Saturday forfeit was overturned, the Sunday forfeit upheld, and no expulsion mentioned. There was a certain logic to the ruling, since the game played 10 miles away in New York on the same date had been called due to darkness about 45 minutes before the game in Brooklyn was ended. But owner Byrne was apoplectic with the ruling, and Sporting Life’s local correspondent reported “disgust and contempt” in Brooklyn over it, adding that the decision had “put a keen edge on the desire for jumping out of the American Association and given new zest to the … possibility of Brooklyn joining the (National) League.”4 That is exactly what happened. At the Association’s December meeting, both Brooklyn and Cincinnati (which had also had its Sunday games interfered with by authorities) quit the AA and joined the NL, while Baltimore and Kansas City left for the minor leagues. The emasculated American Association limped through two more seasons before finally succumbing to the buyout that brought four of its members into the National League in 1892.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1889.

2 Ibid.

3 The Republic, St. Louis, September 8, 1889.

4 Donnelly, J.J. Sporting Life, October 2, 1889.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Bridegrooms 6

St. Louis Browns 4

Washington Park

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.