September 22, 1959: White Sox clinch first American League pennant in 40 years

As the Chicago White Sox took the field at Cleveland Stadium on the night of September 22, 1959, the city of Chicago was bracing for a celebration. A victory over the Cleveland Indians would clinch the American League pennant for the White Sox—the first AL crown for the Sox since 1919. That 1919 league championship would be tainted forever when eight members of the team were permanently banished from baseball for allegedly throwing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds; a pennant in 1959 would help put aside some painful memories for the Sox franchise.

As the Chicago White Sox took the field at Cleveland Stadium on the night of September 22, 1959, the city of Chicago was bracing for a celebration. A victory over the Cleveland Indians would clinch the American League pennant for the White Sox—the first AL crown for the Sox since 1919. That 1919 league championship would be tainted forever when eight members of the team were permanently banished from baseball for allegedly throwing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds; a pennant in 1959 would help put aside some painful memories for the Sox franchise.

The ’59 Sox weren’t making things easy for their fans. A five-hit 1-0 shutout by right-hander Bob Shaw over the Detroit Tigers on Friday, September 18, had reduced the White Sox “magic number” (the combination of Sox victories and/or Indians losses needed to clinch the pennant) to two. But the magic number had stayed at two on Saturday and Sunday, as the Sox suffered a pair of 5-4 losses to the Tigers while the uncooperative Indians were logging a pair of victories over the Kansas City Athletics (by scores of 13-7 and 4-3). Both teams were idle on Monday, and the Sox entered Tuesday’s showdown in Cleveland with a 91-59 record, three and a half games ahead of the Tribe (87-62). Interest in Tuesday night’s game was so strong in Chicago that WGN-TV, the club’s television outlet, arranged to televise the game “as a public service,” with Jack Brickhouse and Lou Boudreau describing the action.1 Prior to then, WGN had televised only home day games involving the White Sox and Chicago Cubs.

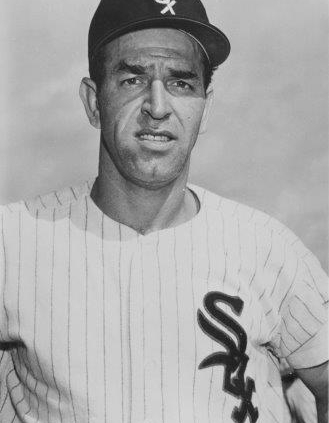

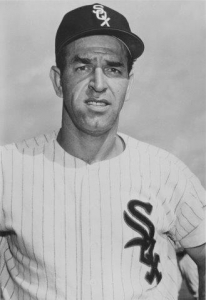

To face the Indians, Sox manager Al Lopez selected staff ace Early Wynn, who entered the game with a league-leading 20 wins (20-10 record). Wynn and Lopez shared a long history, as Lopez had managed the Indians from 1951-56, years in which Wynn had recorded four 20-plus victory seasons for the Tribe. When the White Sox acquired Wynn in a trade with the Indians in December of 1957, Lopez had commented that “If there was one game I had to win, my pitcher would be Early Wynn.”2 Indians manager Joe Gordon countered with rookie right-hander Jim Perry, who entered the contest with a 12-9 record and an excellent 2.61 ERA. Perry was only 23 years old, and his experience paled in comparison to the 39-year-old Wynn, who was in his 19th major-league season and had posted 269 major-league wins. But Indians general manager Frank Lane, who had once held the same job with the White Sox (1949-55) was confident. “He’s a great money player,” Lane said of Wynn, “but we’re going to beat him.”3

The crowd of 54,293 watched Perry set down the White Sox in order in each of the first two innings. Cleveland threatened in the second when ex-Sox star Minnie Minoso (who had been traded to the Indians in the deal for Wynn) was hit in the left wrist to lead off the frame, and Russ Nixon followed with a single that advanced Minoso to third. Rocky Colavito then lofted a flyball to left field; Sox left fielder Al Smith, who had come to Chicago in the Wynn-Minoso trade (Fred Hatfield had gone to Cleveland along with Minoso), made the catch and “threw on the fly to [catcher John] Romano, who put the ball on the sliding Minoso”4 for a double play. (“Minnie and I used to have a bet—who could throw out the other guy,” Smith would later recall. “That year [1959], he didn’t throw me out once. I threw him out three times.”)[5] Woodie Held popped out to end the inning. Frank Lane, who was watching the game from the press box, unloaded on his own team for the failure to score: “That guy at third [Coach Jo-Jo White] doesn’t think at all. He shouldn’t have sent Minnie home. It was only a short fly… That Colavito can’t drive in a run except the ones he drives himself in on a homer.”6

The White Sox broke through against Perry in the third. Bubba Phillips singled to center with one out; after Perry retired Wynn, Luis Aparicio doubled home Phillips, and Aparicio raced home on another double by Billy Goodman. Cleveland got a run back in the fifth. Held walked to lead off the inning. After pinch-hitter Chuck Tanner batted for third baseman George Strickland and struck out, another pinch-hitter, Gordy Coleman, singled. Jim Piersall then singled to center to drive in Held, with Coleman advancing to third. As Vic Power stepped to the plate, Lane grumbled: “This’ll be a double play. All Power does is hit into double plays.”7 Sure enough, Power grounded to Aparicio, who started a 6-4-3 DP to end the inning, with Lane lamenting that the Tribe should have opted to have Power lay down a squeeze bunt.

Mudcat Grant relieved Perry in the sixth, and after retiring Romano to start the inning, gave up back-to-back home runs to Smith and Jim Rivera to increase the White Sox lead to 4-1. In Cleveland’s half of the inning, Tito Francona led off with a single and Russ Nixon hit a one-out single to move Francona to third. After Colavito drove home Francona with a sacrifice fly to center field, Lopez replaced Wynn with Bob Shaw, who retired Held to end the inning. Cleveland threatened again in the seventh when Piersall and Power hit two-out singles, but Shaw got Francona to ground out to end the inning.

Cleveland mounted one last threat in the bottom of the ninth. Shaw retired Held to open the frame, but Jim Baxes singled off the pitcher’s glove. Indians manager Joe Gordon then allowed pitcher Jack Harshman, a one-time minor-league slugger as a first baseman, to hit for himself, and Harshman came through with a single that moved pinch-runner Ray Webster to second, and Piersall hit an infield single off Fox’s glove to load the bases. With Vic Power due up and Billy Pierce, Turk Lown and Jerry Staley all warming up, Lopez brought in Staley, a sinker-ball specialist. “When the White Sox bought Staley from the Yankees [in May of 1956] he was depending mostly on his knuckle ball,” Lopez had commented about Staley. “Over here he throws mostly the sinker, a real good one with great control.”8 Staley was expecting to get the call. “A situation like that, a ground ball gives you a chance to get a double play and get out of the inning,” he recalled.9

Staley needed only one pitch to bring home a White Sox pennant. Bob Vanderberg recorded Jack Brickhouse’s call on WGN-TV. “Here we go. Power is 1-for-4, an infield single—there’s a ground ball… Aparicio has it! Steps on second throws to first… The ballgame’s over! The White Sox are the champions of 1959! The 40-year wait has now ended!”10

According to Vanderberg, the double play was completed at 9:43 PM Chicago time, setting off celebrations both on the field and back in Chicago. “An estimated 20,000 people gathered in the Loop to salute the victory,” he wrote. “Thousands more began heading for Midway Airport, where the Sox’s planed was scheduled to land around 2 AM.”11 The Chicago Tribune estimated the crowd at Midway at 25,000, The Sporting News at over 100,000.

Along with the excitement about the White Sox pennant in Chicago, there was confusion and even some panic among many of the city’s residents that night. Chicago Fire Commissioner Robert Quinn, a good friend of Mayor Richard J. Daley and a passionate White Sox fan, decided to honor the Sox victory by turning on the city’s air-raid sirens. Many citizens feared that the city was under threat of nuclear attack. “The sirens sounded for about five minutes and brought anything but joyful reaction from thousands of people who thought there was an air raid,” wrote Jerry (later known as Jerome) Holtzman. “Television and radio shows had to be interrupted to explain that the sirens were sounded only to signal the first White Sox pennant in 40 years…. The Illinois Bell Telephone Co. said it handled the heaviest deluge of calls since the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945.”12

“The sirens’ wail made the night memorable, since there was no way for the people of Chicago to know whether the sirens were announcing the White Sox victory or the imminent arrival of the Russians,” wrote Bill Veeck. “I mean, if you were a White Sox fan, you had to figure that it was just your luck for The Bomb to be dropped right after the White Sox won the pennant. What else could follow 1919?”13

Sources

Kalas, Larry. Strength Down the Middle: The Story of the 1959 Chicago White Sox (Chicago: RR Donnelly & Sons, 1999).

White Sox television schedule information from The Sporting News Dope Book 1959.

1] “WGN-TV Will Televise Sox Game Tonight,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1959: 64.

2 Ed Prell, “Lopez calls on Wynn to Clinch Title,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1959: 61.

3 Robert Cromie, “Indian Fans Dream, Rush for Tickets,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1959: 64.

4 Edward Prell, “White Sox Win Pennant!” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1959: 54.

5 Bob Vanderberg, ’59; Summer of the Sox: The Year the World Series Came to Chicago (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc, 1999), 138.

6 David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1959: 57.

7 Ibid.

8 Edward Prell, “Castoff Hurlers Aid Lopez’s Rise,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1959: 65.

9 Vanderberg, 139.

10 Ibid., 139.

11 Ibid., 140.

12 Jerry Holtzman, “Sirens Sound for Chisox; Calls Flood Switchboards,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1959: 8.

13 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck—As In Wreck (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 350.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 4

Cleveland Indians 2

Cleveland Stadium

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.