1918 World Series: Boston Red Sox vs. Chicago Cubs

This article was written by Allan Wood

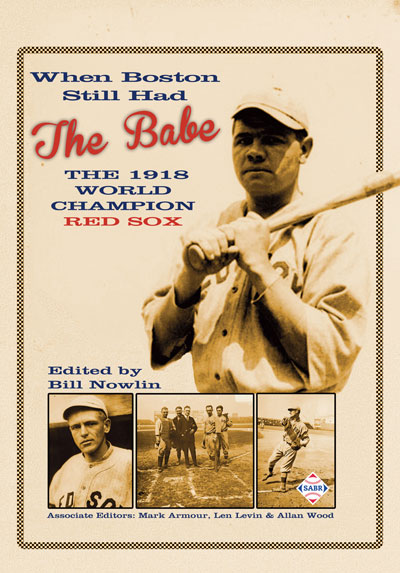

This article was published in 1918 Boston Red Sox essays

The Chicago Cubs won the 1918 National League pennant by 10½ games and were solid favorites to win the World Series against the Boston Red Sox.

The Chicago Cubs won the 1918 National League pennant by 10½ games and were solid favorites to win the World Series against the Boston Red Sox.

Hugh Fullerton, a sportswriter for the New York Evening World, looked at the Cubs–Red Sox match-up using a personal statistical formula – “Position Strength” – which included “hitting, waiting out pitchers, long-distance hitting, getting hit by pitched ball, speed” and defense.

Fullerton calculated “each man’s value and then figure[d] how his values, both in attack and defense, will be affected by the opposing team.” Fullerton concluded that the margin was “too small to indicate any marked superiority for either team,” but in his final analysis, he believed the Cubs would prevail in six games.

Many other writers agreed, including Henry Edwards of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Thomas Rice of the Brooklyn Eagle, Bill Phelson of Baseball Magazine, and George S. Robbins of the Chicago Daily News. New York syndicated writer Joe Vila gave the Cubs an edge because of its left-handed pitchers and the “yowling, heartless rooters” at Comiskey Park. (Cubs owner Charles Weeghman had decided to use Comiskey Park, which had a greater seating capacity.)

However, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack thought the schedule (three games in Chicago and the remaining contests at Fenway Park) gave Boston an edge. Eddie Hurley of the Boston Evening Record said the Red Sox “are the better defensive club” but questioned whether the team could score enough runs to win. Burt Whitman of the Herald and Journal said Boston would win in six games: “On paper, the Cubs figure ‘to beat’ the Red Sox . . . [but] this series will not be played on a typewriter.”

The Cubs had finished the regular season with a better record than Boston (84-45 to 75-51) and a superior team batting average (.265 to .249), on-base percentage (.325 to .322), and slugging percentage (.342 to .327). The Cubs had also scored more runs (538 to 474).

Rookie shortstop Charlie Hollocher led the National League in hits (161) and total bases (202), was second in on-base percentage (.379), third in stolen bases (26), and fourth in runs scored (72) and batting average (.316). He was the only Chicago regular to hit over .300.

Les Mann, Chicago’s 24-year-old left fielder, hit .288 and reached personal bests in doubles, stolen bases and walks. Center fielder Dode Paskert, at age 37, had his best season since 1912, batting .286 and finishing with 125 runs produced (RBI + runs scored – HR), second behind George Burns of the Giants (127).

Chicago’s team ERA was lower than Boston’s (2.18 to 2.31), although the Red Sox led the majors with 26 shutouts (the Cubs had 23). Both teams had the lowest opponents’ batting average in their respective leagues, Boston at .231 and Chicago at .239.

Chicago would rely heavily on its top left-handed pitchers, Jim Vaughn and Lefty Tyler. The Red Sox were 11-18 in games started by lefties.

Vaughn led the National League in wins (22), shutouts (8), ERA (1.74), strikeouts (148), and lowest opponents’ batting average (.208) – the best season of his 10-year career. And while he had a hard fastball and good control, Vaughn also carried a reputation of buckling in important games.

The ERAs of the four Red Sox starters were all between 2.11 and 2.25. Joe Bush had the lowest ERA on the staff, but bad luck and poor run support left him with a 15-15 record. In the season’s last month, Bush had gone 1-6; four of those losses were by scores of 2-0, 1-0, 2-1, and 1-0.

In the 15 years since the National and American Leagues had begun playing a post-season series, a team from either Boston or Chicago had been involved 11 times, but never during the same year.

Thursday, September 5

Comiskey Park, Chicago

Game One: Red Sox 1, Cubs 0

Rain had pushed the start of the series ahead one day. The National Commission’s original schedule had included no weekend games, which puzzled the players on both teams, but now, thanks to the postponement, Game Three would be played on Saturday.

Early rumors were that either Carl Mays or Joe Bush would start for Boston, but manager Ed Barrow went with Ruth in the opener. This was Ruth’s second World Series start. In Game Two of the 1916 series, he beat Brooklyn 2-1, pitching all 14 innings (still the longest World Series game by innings).

Babe had been batting in the cleanup spot since early May, but for the World Series, Barrow put him back down at the bottom of the order.

Ruth got two quick outs in the bottom of the first, before Les Mann singled and stole second. Dode Paskert followed with a single and Fred Merkle walked. With the bases loaded, Ruth got Charlie Pick to fly out to George Whiteman in left-center field.

Whiteman opened the top of the second with a single and was bunted to second by Stuffy McInnis, but Everett Scott and Fred Thomas couldn’t advance him.

Ruth retired the bottom three of the Chicago order in the second and worked around a leadoff single in the third.

Vaughn had control problems early on, going to full counts on several Boston batters and allowing a hit in each of the first three innings. He began the fourth by walking Dave Shean. Amos Strunk attempted to sacrifice him to second, but popped up the first pitch to Vaughn.

Whiteman singled to left – Cubs shortstop Charlie Hollocher seemed out of position – and Shean moved up to second. With McInnis at the plate, Barrow called for a hit-and-run. Stuffy smacked Vaughn’s 1-0 pitch to left field. The ball rolled slowly on the soggy grass and Les Mann’s hurried throw to the plate was not in time.

With a 1-0 lead, Ruth settled into a rhythm, retiring the Cubs in order in the fourth and getting two quick outs in the fifth before hitting Max Flack with a pitch. Hollocher flew out to center to end that inning.

Paskert and Merkle both singled with one out in the bottom of the sixth, and Barrow told Sam Jones and Joe Bush to start loosening up. Charlie Pick moved the runners up to second and third with a ground ball to first base and when Ruth started Charlie Deal off with two balls, the Chicago crowd started to make some noise.

Ruth battled back and Deal fouled off three straight pitches before swinging at what was probably ball four and flying out to Whiteman in left center.

Both teams went down in order in the seventh and eighth innings. The Red Sox tried to get an insurance run in the ninth when Shean lead off with a walk. Strunk sacrificed him to second, but Whiteman struck out and after McInnis was intentionally walked, Everett Scott grounded back to the mound.

Ruth retired the first two batters in the bottom of the ninth – Merkle flew to left and pinch-hitter Bob O’Farrell popped to third – but Deal reached on an infield single. Bill McCabe pinch-ran. Cubs catcher Bill Killefer swatted the ball to deep right field. Harry Hooper caught it on the run and Boston had taken Game One.

It was the first shutout in a World Series opener since 1905, and only the second 1-0 World Series game in 13 years. Coupled with his victory in 1916, Ruth had now pitched 22 1/3 consecutive scoreless World Series innings. Christy Mathewson’s record of 28 innings was within reach in his next start.

Shean reached base three times (two singles and a walk) for Boston and scored the game’s only run. Whiteman singled twice, and made five catches in left field, three of which were tough chances on a windy afternoon. Ruth went 0-for-3, lining out to center and striking out twice.

The crowd of only 19,274 was roughly 13,000 fewer fans than had attended the first game of the 1917 Series, which had also been played at Comiskey Park.

Friday, September 6

Comiskey Park, Chicago

Game Two: Cubs 3, Red Sox 1

Ed Barrow went with Bullet Joe Bush in the second game, figuring that Carl Mays’s submarine delivery would baffle the Cubs and either put Boston up by three games or break a Series tie.

The weather was perfect — clear skies, 70 degrees — but the turnout was only slightly larger than the day before — a crowd of 20,040. One sportswriter counted fewer than 100 women in attendance, quite low for a World Series game.

Bush and Tyler had faced each other in Game Three of the 1914 World Series at Fenway Park, Tyler for the Boston Braves and Bush for the Philadelphia Athletics. In that game, Bush’s 12th-inning error allowed the Braves’ winning run. Seven players from that Series were in uniform today, including Mann, Charlie Deal, Stuffy McInnis, Wally Schang, and Amos Strunk. Cubs manager Fred Mitchell had been the Braves’ manager in 1914.

Facing another lefty, Barrow again started George Whiteman in left field, which left Babe Ruth was on the bench.

There had been some heckling in the opener, but things got much more intense in Game Two. In the first inning, when leadoff batter Harry Hooper tried to steal second base, Dave Shean stepped across the plate, bumping catcher Bill Killefer’s right arm with his bat. Shean was called out on strikes and Hooper ruled out on Shean’s interference. In the bottom of the first, the Cubs believed Amos Strunk intentionally dropped a popup in shallow center to force speedy Charlie Hollocher at second base, leaving a slower runner on first.

Bush had trouble controlling his fastball, so he relied more on his curve, which was not his best pitch. He walked Fred Merkle to start the second inning, then gave up a bunt single to Charlie Pick. After Charlie Deal popped out, Killefer drilled a first-pitch double down the right field line, scoring Merkle. With the Red Sox infield playing on the grass, Tyler grounded a ball up the middle. Shortstop Everett Scott dove to his left, but it scooted past him. Pick scored and Killefer rounded third. Strunk’s throw home was too late to get Killefer, so Sox catcher Sam Agnew came forward towards the mound, got the ball on one hop and fired to second. Scott slammed a hard tag on Tyler.

Otto Knabe, the Cubs’ first base coach, had been yelling at Bush throughout the three-run rally. Knabe had also baited Babe Ruth the previous day. At the end of the second inning, as the Red Sox left the field trailing 3-0, Heinie Wagner walked across the infield to take his spot in the third base coaching box; he met Knabe going in the same direction, towards the Cubs dugout. It is not clear exactly what was said, but both men started cursing. Wagner pointed to the alleyway leading to the Cubs clubhouse — challenging Knabe to a fight.

Once the men were in the Cubs dugout, Wagner grabbed Knabe’s arm and tried dragging him along the floor. Knabe quickly subdued Wagner, and Jim Vaughn apparently knocked Wagner down before he, Knabe, Claude Hendrix, and a few others started punching. Wagner later claimed Knabe had also kicked him while he was on his back. “I wouldn’t mind it if I was hit with a fist,” he later said.

When Wagner finally emerged from the dugout, his hair was a mess, his face pale and bruised, the back of his uniform torn and muddy. The umpires did not get involved. Afterwards, third base umpire Hank O’Day, who had been close to the Cubs dugout, said he hadn’t seen or heard anything.

After this incident, Bush began pitching almost exclusively inside — way inside. After Hollocher grounded out, Bush buzzed a fastball near Mann’s head. Mann cursed Bush, then pushed a bunt up the first base line. Stuffy McInnis made the play unassisted, but when Bush dashed off the mound to cover the bag, he tried tripping Mann on his way to first. Then Bush made the next batter, Dode Paskert, duck away from a beanball before retiring him on an infield pop-up.

Tyler walked the Red Sox leadoff batter in each of the first three innings, but the Red Sox were unable to exploit his lack of control. They didn’t force him to throw strikes, swinging early in the count and chasing poor pitches.

Chicago had an opportunity to widen its lead in the sixth when Hollocher tripled into the right field corner. With the infield in, Hollocher could not score when Mann grounded out. Agnew tried to pick off Hollocher, but his throw got under Fred Thomas’s glove. Thomas deliberately tangled himself up with Hollocher, so the runner couldn’t get up and advance. Already in a foul mood, the crowd howled at Thomas.

Hollocher broke for home when Dode Paskert chopped a grounder to short. It was a foolish play, perhaps borne of frustration, as Scott’s throw to Agnew was in plenty of time for the out.

Boston had very little luck against Tyler. Over the course of 20 batters, from the second inning to the end of the seventh, the Red Sox managed only one hit. In the eighth, Wally Schang pinch-hit for Agnew and singled. After Bush flew out, Hooper singled to right. Schang tried to go to third, but Max Flack made a perfect one-hop throw to Charlie Deal and Schang was cut down. It was a crucial mistake — instead of runners at first and second and one out, Boston had a man at first and two outs. Shean bounced to first and the threat vanished.

With the Red Sox down to their last three outs, Amos Strunk led off the ninth with a triple over Flack’s head in right. Whiteman followed with another triple, this one over Paskert’s head in center. Chicago’s lead was now 3-1 and the potential tying run (Stuffy McInnis) was at the plate.

Cubs manager Fred Mitchell had Phil Douglas and Claude Hendrix in the bullpen, but he stayed with Tyler. Instead of squeezing the runner home, McInnis swung away. He tapped a weak grounder right back to Tyler, who checked the runner and threw McInnis out. Tyler then walked Everett Scott.

Barrow thought about sending Babe Ruth up as a pinch-hitter, but opted for another pitcher: Jean Dubuc, who batted right-handed. It was an odd choice. If Barrow was intent on having a pitcher at the plate, Carl Mays, whose .357 on-base percentage was fourth best on the team, would have been a wiser choice.

Dubuc fell behind in the count 1-2, then fouled off four consecutive pitches before swinging and missing a curve about a foot off the plate. Schang was next, and Ruth waited on the dugout steps, black bat in hand, ready to hit for Bush if Schang could keep the inning alive.

Considering how hard Tyler had worked to get Dubuc, Schang should have looked at a few pitches. But he swung at the first one he saw, and popped it up. Hollocher moved a few steps to his right, made the catch, and ran quickly off the field, disappearing into the dugout with the baseball still in his glove. The Series was tied at one game apiece.

For the Red Sox, it was a game of missed opportunities. Boston’s leadoff batter had reached base in five of the first eight innings. The Boston sportswriters were dumbfounded by Barrow’s ninth-inning strategy. Eddie Hurley of the Boston Evening Record thought letting Ruth watch the entire inning from the bench was “nothing but criminal”.

Saturday, September 7

Comiskey Park, Chicago

Game Three: Red Sox 2, Cubs 1

The Red Sox were convinced that spitballer Claude Hendrix would pitch for Chicago, so they were shocked when Jim Vaughn came back to pitch on one day’s rest. The fans were also surprised, and they gave Vaughn a standing ovation as he walked to the mound. (Another Cubs lefty on the hill also meant Babe Ruth remained on the bench.)

A light rain started to fall in the top of the second inning. Home plate umpire Bill Klem saw no reason to pause the game, and it drizzled off and on all afternoon.

Boston drew first blood with one out in the fourth inning. Vaughn worked Whiteman inside and hit him in the back. McInnis tried to hit-and-run on the first pitch, but fouled it off. When he swung and missed the next pitch, Whiteman was trapped off the bag. Catcher Bill Killefer hesitated for a moment before throwing to first baseman Fred Merkle, and that slight pause allowed Whiteman to dive back safely.

Vaughn’s 0-2 pitch was high and inside and McInnis punched it into left field. Schang followed with a single to center; Whiteman scored and McInnis raced to third.

Ed Barrow was not a fan of the suicide squeeze, but with Scott, a good bunter, at the plate, the play was on. Scott dropped the first pitch right in front of the plate — a beautiful bunt — too far out towards the mound for catcher Bill Killefer to field it. Vaughn grabbed it, but when he tuned to throw to first, he saw that Merkle also had run in on the bunt and second baseman Charlie Pick hadn’t covered first. McInnis scored and Boston led, 2-0.

Thomas followed with a single to right field, his first hit of the Series. Heinie Wagner wanted Schang to stop at third, which would have loaded the bases and kept Vaughn on the ropes, but Schang ran through the stop sign. Max Flack’s throw was perfect and Schang was easily tagged out. Mays lined out to center field and Vaughn escaped with minimal damage.

Carl Mays was well-rested – he hadn’t pitched since his back-to-back wins against Philadelphia a week earlier – and he was nearly perfect. After walking the first hitter he faced, Mays set down 10 in a row, breezing through the third inning on only five pitches.

Facing Mays for the second time, however, the Cubs had a better read on his delivery and hit him hard. Les Mann doubled with one out in the fourth. Paskert whacked a fly ball to deep left center that looked like it might carry into the bleachers. Whiteman sprinted back, until he was literally against the wall — and grabbed the ball with a leap at the fence.

After his near-disastrous fourth inning, Vaughn was untouchable. He kept the ball in the infield in both the fifth and sixth innings, and at one point retired 13 Red Sox batters in a row. Meanwhile, his teammates repeatedly threatened to come back against Mays.

Charlie Pick’s fifth-inning grounder slipped under Everett Scott’s glove and slowly rolled into center field. By the time Amos Strunk got it back to the infield, Pick was on second. One out later, Killefer banged a single off Scott’s bare hand into left. Whiteman charged in, but there was no play to make. Pick scored, cutting Boston’s lead to 2-1. Killefer, perhaps thinking the Red Sox defense was unnerved, broke for second on Mays’s 2-0 pitch to Flack. Schang’s throw was low, but Scott dug it out of the dirt and put the tag on Killefer’s foot as he slid into the bag.

Mann and Paskert both singled with two outs in the sixth, but were stranded when Merkle struck out swinging. With one out in the seventh, Deal reached on an infield hit to third. All of Chicago’s six hits had come within the last 14 batters — nearly every other Cub was reaching base. Mays battled back: Killefer bounced back to the mound and Vaughn flew to left.

In the eighth, Mays retired the top of the Cubs lineup in order and got the first two batters in the bottom of the ninth. Facing the daunting prospect of needing to win three games at Fenway Park, Chicago tried to rally.

Charlie Pick was safe on an infield hit to second. Left-handed hitter Turner Barber pinch-hit for Deal. Mays’s first offering was ball one. On the next pitch, Pick sprinted to second. Wally Schang’s throw was right on the money — but Shean bobbled it. Pick made a great slide and the Cubs were still alive.

Barber smacked a line drive that landed about six inches foul down the third base line, then Schang set up outside. But Mays threw too far outside. The ball glanced off Schang’s mitt and rolled a few yards to his left behind the plate. As Pick ran to third, Schang fired a throw to Fred Thomas. Pick and the baseball arrived at almost the same time. Umpire George Hildebrand began calling Pick out, then saw Thomas hadn’t held onto the ball. He spread his arms: “Safe!”

Thomas and Pick were tangled in the dirt. Pick had overslid the bag and was on his stomach, trying to crawl back and touch the base with his hand. Thomas was yelling at Hildebrand, arguing that Pick had kicked the ball out of his glove. Cubs manager Fred Mitchell, coaching at third base, shouted at Pick to run home.

The ball had stopped rolling about 20 feet away in foul territory. Pick took off. Thomas finally ran over and grabbed the ball. He had no time to set himself, but his throw was straight and true. Pick slid in, spikes high, and Schang tagged him in the ribs a foot or two from the plate. The game was over – and the crowd exhaled a huge, collective groan. The Cubs had come close, but Boston’s razor-thin victory gave them a 2-1 lead in the Series, with all remaining games at Fenway Park.

Sunday, September 9 – Traveling from Chicago to Boston

Before the 1918 season began, the National Commission decided to allow the top four teams in each league to share some of the gate receipts of the first four World Series games. This decision, coupled with low attendance and reduced ticket prices, meant that the shares for the winning and losing teams could be 75% smaller than they had been in 1917.

During the train ride to Boston, players on both teams discussed whether anything could be done. Some felt the Commission was deliberately exploiting them and wanted to abandon the series immediately. Eventually, the players came up with two proposals: either guarantee shares of $1,500 and $1,000 or postpone the revenue-sharing plan until after the War. Harry Hooper and Dave Shean of the Red Sox and Les Mann and Bill Killefer of the Cubs tried meeting with Commissioner August Herrmann on Sunday afternoon, but he refused to see them, saying that he couldn’t make any official decisions without the other commissioners present. Herrmann and the players agreed to meet in Boston on Monday morning.

Monday, September 9

Fenway Park, Boston

Game Four: Red Sox 3, Cubs 2

On Monday morning, the full Commission refused to speak to the players, saying they needed to know what the actual revenues from the fourth game would be, and suggested getting together after that afternoon’s game.

Game Four was the Red Sox’s first World Series game in Fenway Park since 1912. Their home games in 1915 and 1916 had been played at Braves Field, which had a larger seating capacity.

Babe Ruth took the mound with yellow iodine stains visible on his left hand. He had injured his pitching hand the night before fooling around with fellow pitcher Walt Kinney on the train. Ruth was trying to break Christy Mathewson’s record of 28 consecutive scoreless World Series innings (his streak was at 22 1/3).

Left fielder George Whiteman was again batting cleanup and Ruth was hitting sixth. Babe had been in the sixth spot only once before all season — back on May 6, the day he debuted at first base. Barrow gave no explanation for the switch.

It was obvious from the first inning that Ruth had difficulty getting the proper spin on his curveball. Chicago put men on base in each of the first three innings, but was turned back by Ruth’s gutsy pitching and Boston’s airtight infield.

The game was scoreless in the fourth when Tyler walked Dave Shean. With right-handed hitters George Whiteman and Stuffy McInnis coming up, Amos Strunk tried to bunt. After two failed attempts, he lined out to center field. Shean took advantage of Tyler’s leisurely windup and stole second without a throw. The Fenway crowd stomped its feet in unison, clamoring for a run. Tyler couldn’t find the strike zone and walked Whiteman. The roar increased as Claude Hendrix came out of the third-base dugout and began warming up.

McInnis hit the ball right back at Tyler. The pitcher grabbed it, then paused for a split second before throwing to Deal at third base and forcing Shean. His slight delay meant the relay to first was late. Boston now had runners at first and second with two outs — and Babe Ruth was up.

Tyler looked over at his dugout, waiting for a sign from his manager. Should he walk Ruth intentionally, loading the bases for Everett Scott (who was 1-for-11 in the Series)? Should he pitch to Ruth? Was Hendrix coming in?

All summer long, Ruth had been walked in situations like this, often as early as the first inning. Ruth hadn’t faced Tyler in Game Two and he had yet to hit safely in a World Series game, wearing an 0-for-10 collar dating back to 1915.

Mitchell decided Tyler should pitch carefully to Ruth, and hope the Big Fellow would chase a bad ball. Max Flack was at normal depth in right field; he had been much deeper on Ruth in the second inning, but Babe had grounded out, and now he stayed where he was.

Tyler’s first three pitches were low and outside, well off the plate. Ruth was patient and everyone could see this was an “unintentional intentional walk.” Then Tyler slipped a slow curve on the inside corner. Ruth took a big swing and missed, spinning nearly all the way around.

Ruth thought Tyler’s next pitch was too high and a bit outside. He tossed his bat aside and started jogging to first. “Strike two!” Brick Owens yelled above the din. Ruth glared at Owens and kicked the dirt.

Killefer called for a curveball — Tyler’s strongest pitch and Ruth’s weakest — but the lefty came back with another fastball, and this time it remained belt high. Ruth pulverized it, sending it screaming into right field. Flack took a half-step forward, not seeing the ball clearly until it rose out of the shade of the grandstand. By that time, it was too late. He turned, ran back towards the bleachers. It was a triple, and Whiteman and McInnis scored easily. Boston led 2-0.

Everett Scott tried twice to squeeze Ruth home before flying to center for the third out. The Fenway crowd never stopped roaring as Ruth ran back to the dugout, grabbed his mitt, and returned to the mound.

Ruth began losing his control in the sixth inning —the iodine on his finger was rubbing off on the ball, causing it to sail — and it was only Boston’s strong infield that saved his lead. Tyler walked to start the inning. Flack grounded straight back to Ruth. He turned and fired to second base, but it was a poor throw that got by Scott. Shean, however, was positioned only a few feet behind the base. He was on his knees when he gloved Ruth’s errant toss, then crawled on his stomach in the dirt, tagging the bag with his mitt just ahead of Tyler’s foot.

The next two Cubs grounded out and it was official: Ruth had set a new World Series record of 28 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings.

But in the seventh, Ruth’s control got worse, as he walked Fred Merkle and Rollie Zeider with one out. Joe Bush began warming up. Pinch-hitter Bob O’Farrell hit the ball hard up the middle. Scott raced over, scooped it up, and flipped to Shean, who fired to first for an inning-ending double play.

After Ruth’s triple, Tyler retired the next seven Boston hitters and prayed his teammates would rally. Killefer walked to open the eighth, Ruth’s third walk to his last four batters, his fourth free pass in two innings. Bush, still warming up, was joined by Carl Mays.

Claude Hendrix, a right-handed hitting pitcher, batted for Tyler. Hendrix had hit .264 in 1918, with three triples and three home runs. Mitchell’s move paid off when Hendrix singled to left. Killefer stopped at second. Flack bunted the first pitch foul, then Ruth threw one in the dirt. It skipped past Agnew’s glove for a wild pitch, and the Cubs had men at second and third.

The Cubs bench was heckling Ruth from the dugout and anxious Red Sox fans were poised on the edge of their seats. Flack bounced the next pitch to first and McInnis gloved it along the line and tagged Flack for the first out. Hendrix must have thought Killefer broke from third on the play because he was halfway to third before he realized his mistake. Everett Scott yelled for the ball, but Hendrix was able to get back to second.

Cubs manager Mitchell noticed the gaffe and even though he had wanted Hendrix to pitch the eighth inning, he yanked him and sent in Bill McCabe as a pinch-runner at second.

Charlie Hollocher, slumping at 1-for-13 in the Series, hit a sharp ground ball to Shean. The second baseman might have had a shot at Killefer at home, but he opted for the sure out at first. Killefer scored and Boston’s lead was 2-1. Les Mann singled to left and McCabe’s run tied the game at 2-2. Ruth avoided further trouble when Paskert grounded out to third. Ruth’s scoreless innings record ended at 29 2/3.

When the Red Sox batted in their half of the eighth, they faced a right-handed pitcher – Phil Douglas – for the first time in the Series. Wally Schang, a switch-hitter batting for Sam Agnew, singled to center and took second on a passed ball. Harry Hooper bunted to the third base side of the infield. Douglas’s throw to first was wild and sailed down the right field line. Schang scored to give Boston a 3-2 lead. Douglas then retired the next three hitters: Shean flew out to left, Strunk flew out to center, and Whiteman grounded to third.

In the top of the ninth, Ruth was three outs away from his second victory in the Series, but he was clearly out of gas. When Merkle singled to left and Zeider walked, Barrow decided he had seen enough. Barrow double-switched, bringing in Bush to pitch and sending Ruth (who would bat second in the bottom of the ninth inning, if necessary) out to left field.

Bush’s first batter was Chuck Wortman, who bunted. McInnis raced in from first and fired the ball to third. Merkle was forced by about 30 feet. Next, Turner Barber came up to hit for Killefer. Barber lined the ball on the ground towards Scott. The sure-handed shortstop flipped the ball to Shean, who threw to first for a game-ending double play. Bush had saved the win for Ruth, and the Red Sox were one victory away from their fifth World Series title.

Tyler pitched a much better game than Ruth, allowing only three hits in seven innings, but had no luck or support. Babe gave up seven hits and six walks, and threw one wild pitch, but the game had been a litany of missed opportunities by the Cubs. Much of Chicago’s inability to bring those runners home could be chalked up to the phenomenal play of Everett Scott. The Deacon handled 11 chances flawlessly, several of which robbed the Cubs of hits up the middle. Scott also started two double plays in the final three innings.

The outlook for the Cubs was grim, but back in the 1903 World Series, Boston had trailed Pittsburgh 3-1 before winning four games in a row. However, that had been a best-of-nine series — no team had come back from a 3-1 deficit in a seven-game series.

That evening, Harry Hooper, Everett Scott, Les Mann, and Bill Killefer went to the Copley Plaza Hotel to meet with the National Commission. However, they were told the commissioners had stood them up and gone to the theater instead.

Tuesday, September 10

Fenway Park, Boston

Game Five: Cubs 3, Red Sox 0

The players were finally able to meet with the National Commission on Tuesday morning, but the discussion was fruitless. The commissioners promised to render a final decision after the game, but the players knew if the Red Sox won, the Series would be over and any leverage they held would be gone. So they decided to wait in their locker rooms until a decision was announced. When two of the commissioners showed up at Fenway drunk and in no shape to discuss financial matters, the players again had a choice to make. With nearly 25,000 fans waiting in the stands, they decided to play the game.

Because of the delay, the game began one hour late. Sam Jones hadn’t pitched in eight days and was a little rusty (or perhaps nervous). Max Flack walked on four pitches to start the game and Charlie Hollocher followed with a hard-hit single up the middle. Carl Mays began warming up.

Les Mann bunted the runners to second and third. The Red Sox infield played back, willing to concede an early run. Dode Paskert’s sinking liner to left was caught on the run by George Whiteman. Without stopping to set himself, Whiteman fired the ball to Dave Shean at second base. Hollocher, thinking the ball would drop for a hit, had taken off for third base and was doubled up for the inning’s third out with Flack still 20 feet from the plate.

After pitching complete game losses in the first and third games, Jim Vaughn was once again on the hill. After a leadoff single by Harry Hooper, Vaughn retired seven batters in a row.

In the third, Hollocher walked on four pitches. He took a long lead off first, daring Sam Agnew to try and pick him off. It worked — the Boston catcher called for a pitchout, McInnis took the throw from Agnew and turned towards the bag — but he swiped at nothing but air. Hollocher was safe at second with a stolen base.

Mann followed with a double into the left field corner, scoring Hollocher and giving Chicago a 1-0 lead. After 21 innings in the series, Jim Vaughn was finally pitching with a lead.

It was a dull first three innings for the home fans: Hooper’s first-inning single and Jones’s walk in the third was the extent of the Red Sox offense. The Fenway crowd cheered as Amos Strunk led off the fourth inning with a double to deep right. But the rally fizzled when Whiteman popped up a bunt attempt and McInnis lined into a double play to first base, with Strunk being doubled off second.

In the fifth, Vaughn was likely tiring: he was pitching his 23rd inning in six days. The Red Sox began hitting him hard, but for all their line drives, Boston came up empty.

Jones pitched well through five innings, having allowed only two hits and one run. In the sixth, Hollocher singled and Paskert walked. Merkle singled to left, but George Whiteman was able to gun Hollocher out at the plate to keep the score at 1-0.

Babe Ruth came out to coach first base in the bottom of the seventh, and the crowd roared, hoping his presence on the field might spark a rally. With one out, Whiteman singled, but another double play, the third turned by the Cubs in the last four innings, killed any hope of a run.

Flack drew his second walk of the game in the eighth and Hollocher dropped down a perfect bunt. Jones and Fred Thomas watched the ball roll slowly along the third base chalk line. It struck a small rock, veered in about three inches and stopped. It was Hollocher’s third hit of the game, and with minimal effort Chicago had runners at first and second with nobody out.

Carl Mays and Jean Dubuc were busy in the bullpen as Jones retired Mann on a pop-up. Paskert whacked a double off the wall in left-center and two runs scored.

Scott, Thomas, and pinch-hitter Wally Schang went down in order in the eighth. With one inning left for the Red Sox, trailing 3-0, Hack Miller batted for Jones. He smashed the ball to deep left. Mann ran up the embankment, then slipped and fell. But even though he was sitting on the slope, he managed to catch the ball in his lap. It was a tough break for their team, but the Red Sox fans applauded the unlikely play.

Hooper popped to short left field. It looked like it would drop for a hit, but Hollocher, his hands outstretched, raced back and grabbed it. Instead of a double and a single, Boston was instead down to its last out.

Shean singled into the shortstop hole, but Vaughn zipped three pitches past Strunk for his fourth strikeout and the final out of the game.

Wednesday, September 11

Fenway Park, Boston

Game Six: Red Sox 2, Cubs 1

The players’ committee met with Harry Frazee, Charles Weeghman, and several shareholders of both clubs shortly before 11:00 AM. There were rumors that the owners promised the players a little more money from the gate receipts, but nothing was confirmed.

A morning temperature of 48 degrees and rumors that the sixth game would not be played had left Fenway Park half full.

Barrow selected Carl Mays to pitch, telling Joe Bush that he’d start the seventh game, if it was necessary. Fred Mitchell sent Lefty Tyler back to the Fenway mound and so George Whiteman was in left field and Babe Ruth was on the bench.

Mays was in peak form and retired the first four Cubs on ground balls. Charlie Pick singled, but Mays picked him off first base. Eight of the first nine outs were recorded by the Boston infield.

Tyler faltered in the bottom of the third when he walked Mays on four pitches. After Harry Hooper bunted Mays to second, Tyler walked Dave Shean. Amos Strunk fouled off four pitches before grounding out, putting runners at second and third with two outs. Whiteman’s line drive to right field should have been the final out of the inning, but the ball caromed off Max Flack’s glove for an error. Both Mays and Shean scored easily to give the Red Sox a 2-0 lead.

Flack tried to atone for his error by singling up the middle to start the fourth inning. With one out, Mays hit Les Mann in the leg with a pitch. Catcher Wally Schang recorded a crucial out when he picked Mann off first base. Mays walked Paskert and Flack stole third on ball four. Fred singled to left, scoring Flack and cutting Boston’s lead to 2-1. Pick followed with a hard drive to short right field, very similar to Whiteman’s liner to Flack. Harry Hooper raced in and grabbed it for the final out.

After his stumble in the fourth, Mays regained control and kept the ball down in the strike zone and the Chicago batters hit ground ball after ground ball after ground ball.

In the fifth, Deal and Killefer grounded back to the mound. In the sixth, Mays speared a hot shot headed up the middle and threw to Shean for a force play. The other Red Sox were just as sure-handed. McInnis robbed Hollocher of a hit in the fifth and Schang threw Mann out at second to end the sixth. Fred Thomas knocked down Merkle’s smash in the seventh with his bare hand, recovered the ball in foul territory, and fired a strike across the infield to McInnis.

Cubs manager Fred Mitchell went to his bench in the eighth. Turner Barber lined the ball over shortstop. From the third base dugout, the Cubs could see that the sinking liner was going to drop in front of Whiteman for a single. But just as the ball was about to hit the ground, Whiteman dove forward, stuck his glove out in front of him and snagged the ball a few inches off the grass.

He landed head first and turned a full somersault, bouncing back to his feet with the ball securely in both hands. Whiteman was staggering a bit, but he was also grinning. He tossed the ball in to Everett Scott, who whipped it around the infield. The Fenway crowd leapt to its feet and hollered for a full three minutes.

The next batter, pinch-hitter Bob O’Farrell, popped up to short left field. There was no way Whiteman could reach this one — but Scott glided out and made a difficult catch look almost routine. At that point, with two outs, Whiteman jogged in to the Red Sox bench, rubbing his sore neck. As he crossed the infield, the crowd rose to its feet and applauded again. He was replaced by Babe Ruth.

Mitchell’s third pinch-hitter of the inning, Bill McCabe, lifted a foul ball near the third base stands. Scott caught that one, too, and the inning was over.

The first three hitters in Chicago’s lineup were due up in the ninth and Mays retired them without incident. Flack fouled out to third, Hollocher hit a routine fly to left (when the fans roared, Ruth took a graceful bow), and Mann grounded out to second.

With a 2-1 win, the Red Sox were World Series champions for the third time in four years, and the first franchise to win five World Series titles.

Carl Mays faced only three batters over the 27-man minimum. Chicago hit the ball out of the infield only twice in the last five innings and no Cub reached second base.

Max Flack was immediately compared to Fred Snodgrass, who dropped a routine fly ball that helped the Red Sox beat the New York Giants in the 10th inning of the final game of the 1912 World Series.

Many of the post-game wrap-ups concentrated on how lucky the Red Sox had been.

The Washington Post: “The Red Sox have often been called the luckiest ball club in the world. They lived up to their reputation again today.” Hugh Fullerton also believed “the best team did not win” and that if the Series were played over again, “the majority of the experts who have watched all of the games would wager on Chicago.”

Fred Mitchell was more magnanimous. “All the glory that goes with winning the world championship belongs to Boston. The pitching on both sides was the best in years. It was a tough series to lose. The scores of the games prove that. … I’m not trying to detract anything from the Red Sox. They are a great team and proved it. But I’d like to play the series over again if such a thing were possible. … I shall always contend that with an even break, we would have won. That’s all I have to say on the subject.”

The Red Sox batted only .186 in the series and slugged .233. The Cubs were not much better, batting .210, though Chicago did score 10 runs to Boston’s nine.

Wally Schang led the Red Sox with a .444 average (4-for-9). Both Whiteman and McInnis hit .250 (5-for-20). For Chicago, Charlie Pick was 7-for-18, .389. Merkle, Mann, and Flack each had five hits.

Each team used only four pitchers. For the Cubs, Vaughn and Tyler pitched 50 of their team’s 52 innings.

The winning shares turned out to be $1,108.45 per player, the lowest amount ever awarded to the World Series champions. The Cubs’ losing share was $671 per player.

ALLAN WOOD is the author of Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox. He also writes the blog “The Joy of Sox.” Allan has been writing professionally since age 16, first as a sportswriter for the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press, then as a freelance music critic in New York City for eight years. His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Baseball America, Rolling Stone, and Newsday. He has contributed to two SABR books: Deadball Stars of the American League and Deadball Stars of the National League. He currently lives in Ontario, Canada.