1930 Negro National League

This article was written by Dick Clark - John Holway

This article was published in 1989 Baseball Research Journal

In the latest edition of an ongoing SABR project, researchers tabulated a banner year for Willie Wells, Rube Foster, and other Negro-league immortals.

LATIN AMERICANS called Willie Wells “Diablo”- the Devil. In 1930 he showed why.

The little shortstop hit .404 to lead the western clubs in hitting. (Bill Terry led the white majors with .401; it would have been exciting to see the two compete in the same league.)

Willie also slugged 14 homers, the best in the West, though second to big George (Mule) Suttles, his St. Louis Stars’ teammate who hit 20 splitting his season between St. Louis and New York. A short left-field fence in St. Louis aided both men.1

Wells was also tops in doubles, hits, and total bases, and second in stolen bases. His 17 steals were two more than his close friend and teammate, Cool Papa Bell, and one behind the league leader, Terris McDuffie of Birmingham.2

These figures were compiled by a team of researchers, in and out of SABR, who scoured hundreds of box scores in both black and white newspapers of that year. Although some games will be forever missing from the record, we believe these to be the definitive totals, as complete as they will ever be.

This is part of an on-going project, under editor Dick Clark, to compile the most compete statistics possible for the Negro leagues, whose stats were rarely published, and, when they were, were often inaccurate. The 1921 Negro National League stats were published in the 1985 “Baseball Research Journal.”

We have counted all league games in 1930, about 60 games per team. We have also counted additional games, about 10 or so per team against other top black clubs, such as the independent Homestead Grays. This gives us two sets of figures – league games and total black games. (We did not, however, count contests against white semipro clubs.)

In league games only, rookie Herman (Jabbo) Andrews of Memphis and Birmingham was the batting champ with .399 to Wells’ .397. (If Jabbo or Willie had known how close they were to .400, they might have sat out some games or dropped a few bunts, as Ty Cobb, Roger Hornsby, and others had been known to do, to top the goal.) And Andrews and Dale Alexander are the only batting champions ever traded midway through the season. Andrews remained in the black leagues for 13 years but never approached his 1930 performance again.

Among the pitchers, Eggie Hensley of first-place St. Louis edged Big Bill Foster of the Chicago American Giants as the biggest winner in the West. Hensley was 17-6, compared to Foster’s 16-10 with a sixth-place team overall.

Foster was the younger brother of Hall-of-Famer Rube and is considered by many the best lefty in Blackball annals3. In addition to managing the American Giants, he was also the strikeout king that year, with 134 in 199 innings.

Satchel Paige, who jumped to the East for the first half of the season, finished with a 9-4 record for fifth-place Birmingham. (He was 3-1 at Baltimore for 12-5 overall.)

Paige had 69 Ks in 102 innings. (His Baltimore totals are not yet available.) At Birmingham Satch scored well in TRA (Total Run Average – earned runs were not given in box scores). He had a 3.17, second best in the hard-hitting black league.

The league leader was Ted (Double Duty) Radcliffe, the popular speaker at the 1986 SABR Chicago convention, with 2.80. Duty had a 9-3 record for the champion Stars and tied Foster for the lead in saves, with three. He also batted .289, splitting his time between pitching and catching, hence the moniker “Double Duty,” given him by Grantland Rice.

Two other Birmingham hurlers, who taught Paige his fabled control, also did well in 1930. Harry Salmon was second in strikeouts, and Sam Streeter (see “Smartest Pitcher in Negro Leagues,” BRJ, 1984) led in complete games.

As the season opened, the two top sluggers in the West – indeed, the two top homer hitters in Blackball history – Suttles and Detroit’s Turkey Stearnes4 – joined Paigein jumping to the East. The Depression had settled over the league, and they hoped to make more money from the move.

St. Louis replaced the big Mule with speedy, fancy-fielding George Giles (pronounced Guiles), sometimes called “the Black Terry” and grandfather of Brian Giles, who played infield for the Mets in 1981-83. But the Detroit Stars had no way to replace Stearnes, a seven-time home-run champ. The powerhouse St. Louis club, with a team batting average of .327, won the first half of the split season, beating Kansas City, whose 17-game winning streak was not enough.

Both Suttles and Stearnes returned for the second half. Mule moved to left field, leaving Giles on first.

Stearnes hit only three homers, playing in huge Hamtramck Stadium, but he pumped new life into the Detroiters, who captured the second-half title.

The Monarchs, meanwhile, went on an extended barnstorming tour against the Grays. A bus accident put several key Monarchs out of action, including the great Bullet Joe Rogan, and the Grays won 13 of the 15 contests. The most famous one pitted Homestead’s forty-four-year-old Joe Williams against the Monarchs’ Chet Brewer5. They dueled for 12 innings under the lights, Brewer striking out 19 men and Williams 27 before Joe won it on a one-hitter. Homestead’s eighteen-year-old rookie Josh Gibson got his baptism in the series, hitting .243, with one home run.

In the NNL playoff, St. Louis and Detroit split the first two games in the cozy St. Louis park. Stearnes ripped two homers in the first game and went five-for-five in the second, including a homer. Moving to Hamtramck, Wells and Suttles homered, but Stearnes’ two doubles gave Detroit a 7-5 win. The next day Turkey tripled and became the first man to hit a ball over the park’s distant right-field wall; Wells trumped him with two singles and an inside-the-park homer, as St. Louis won 4-3 to even the Series.

Willie got three more hits in Game Seven, while the St. Louis pitchers finally stopped Stearnes, and St. Louis won 13-7. St. Louis went on to win the Series in nine games. Turk hit .481, the Devil .438.

There was no Black World Series that year against the champions of the East, the Grays (Williams, Gibson, Oscar Charleston), who defeated the New York Lincoln Giants (Pop Lloyd, Chino Smith) in a challenge series. That’s the series when Gibson reportedly hit one ball over the roof of Yankee Stadium and another over the centerfield fence of Forbes Field.

The year came to an end with the death of Rube Foster in the Kankakee insane asylum in December. With him, coincidentally, died his creation, the Negro National League, a victim of the Depression.

But perhaps the most historic event of the year was the birth of night ball. The Monarchs unveiled their lights at Enid, Oklahoma, on April 28 in a game against Phillips University, the same night that Organized Ball saw its first night game about 100 miles away at Independence, Kansas. (The putative pioneer, Des Moines, played its first night game May 2.)

“What talkies are to movies, lights will be to baseball,” Monarch owner J.L. Wilkinson predicted. He took his lights all over the country, including Sportsmen’s Park in St. Louis and Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Cardinal president Sam Breadon ordered a set for his Houston farm team.

The leagues began to crumble under the hard times, and many veteran teams succumbed. But the new invention of lights probably saved both the Negro-league teams and the white leagues in the long decade to come.

Dick Clark and John B. Holway are leading Negro-league historians.

Acknowledgments

The following persons have contributed to the Negro leagues statistics project: Terry Baxter, John Bourg, Harry Brunt, C. Baylor Butler, Elizabeth Cale, Dick Clark, Harry Conwell, Dick Cramer, Deborah Crawford, Paul Doherty, Garrett Finney, Bob Gill, Troy Greene, Richard Hall, John B. Hoiway, John Holway Jr., Men Kleinknecht, Larry Lester, Jerry Malloy, Joe McGillen, Bill Plott, Jim Riley, Susan Scheller, Mike Stahl, A. D. Suehsdorf, Lance Wallace, Edie Williams, and Charles Zarelli.

Notes

1 Wells set the Negro league single-season home-run record with 27 in 1929. That October he bedeviled a white big-league all-star team of Charlie Gehringer, Heinie Manush, Harry Heilmann, and others, hitting .500 with two triples and two steals of home, as the blacks won three games of four. Wells’ lifetime average against white big leaguers was .396.

2 McDuffie would later take up pitching and receive a reluctant tryout from Branch Rickey of the Dodgers in 1944.

3 Foster leads all Negro leaguers in lifetime victories, with a 129-62 record for games researched so far. Paige is fifth with 80-37.

4 Stearnes hit 160 homers in games found so far; Suttles hit 150, and Gibson 137 (most of them in Latin America). “Wells is sixth on the list with 111. All totals are incomplete.

5 Brewer now lives in Los Angeles, where his boys’ baseball program has rescued many youths in trouble and has sent Dock Ellis, Enos Cabell, Bob Watson, and many others to the major leagues.

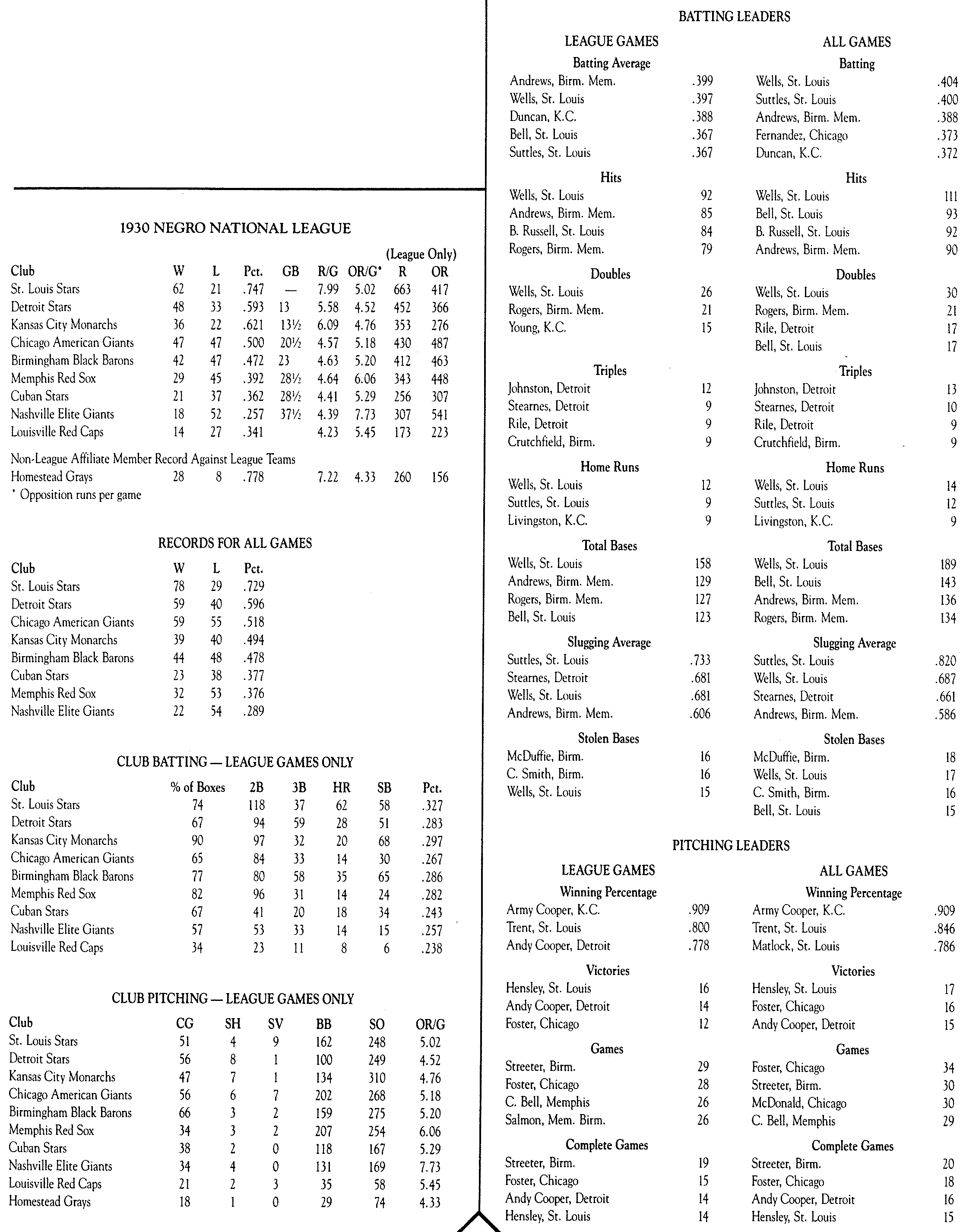

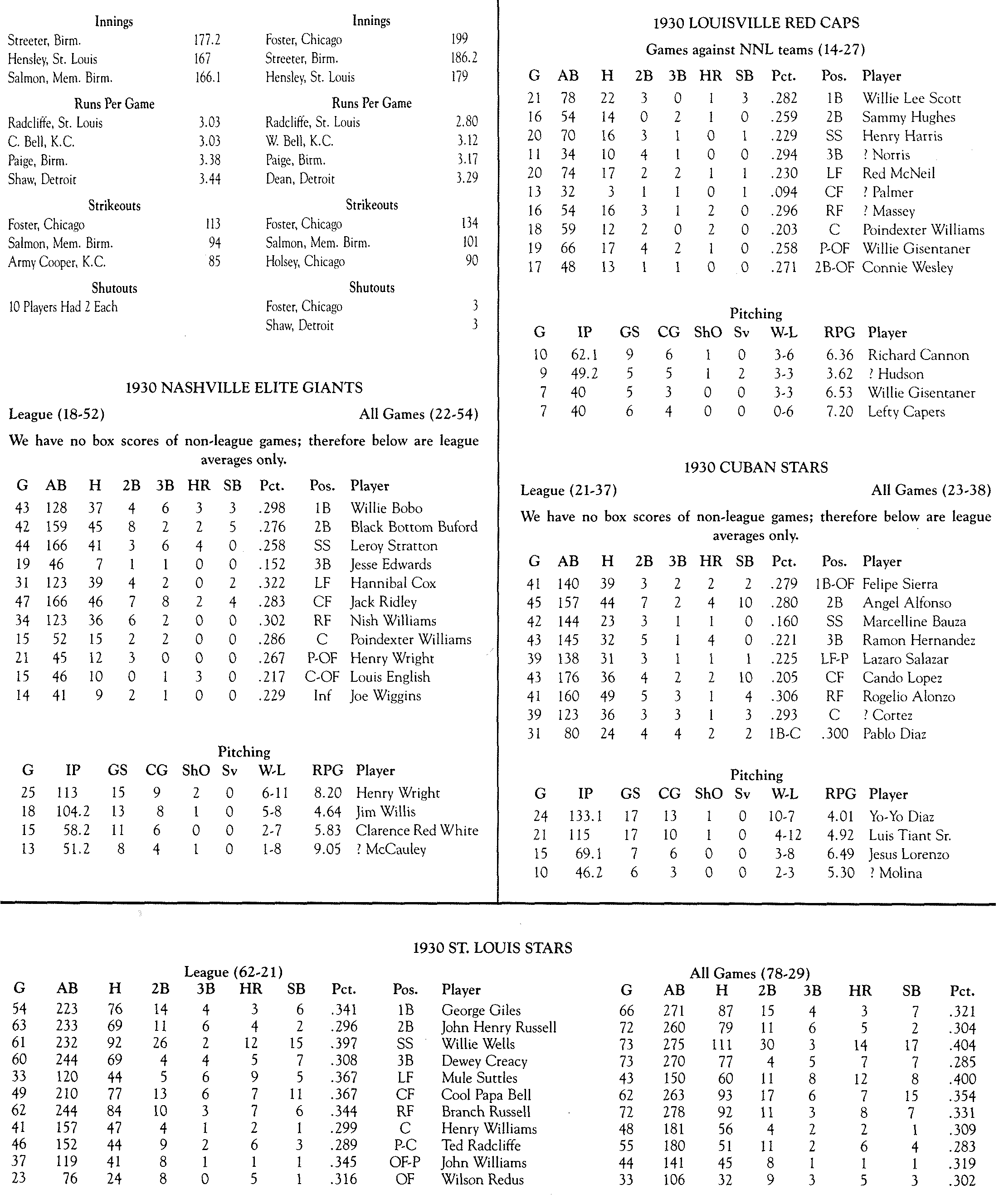

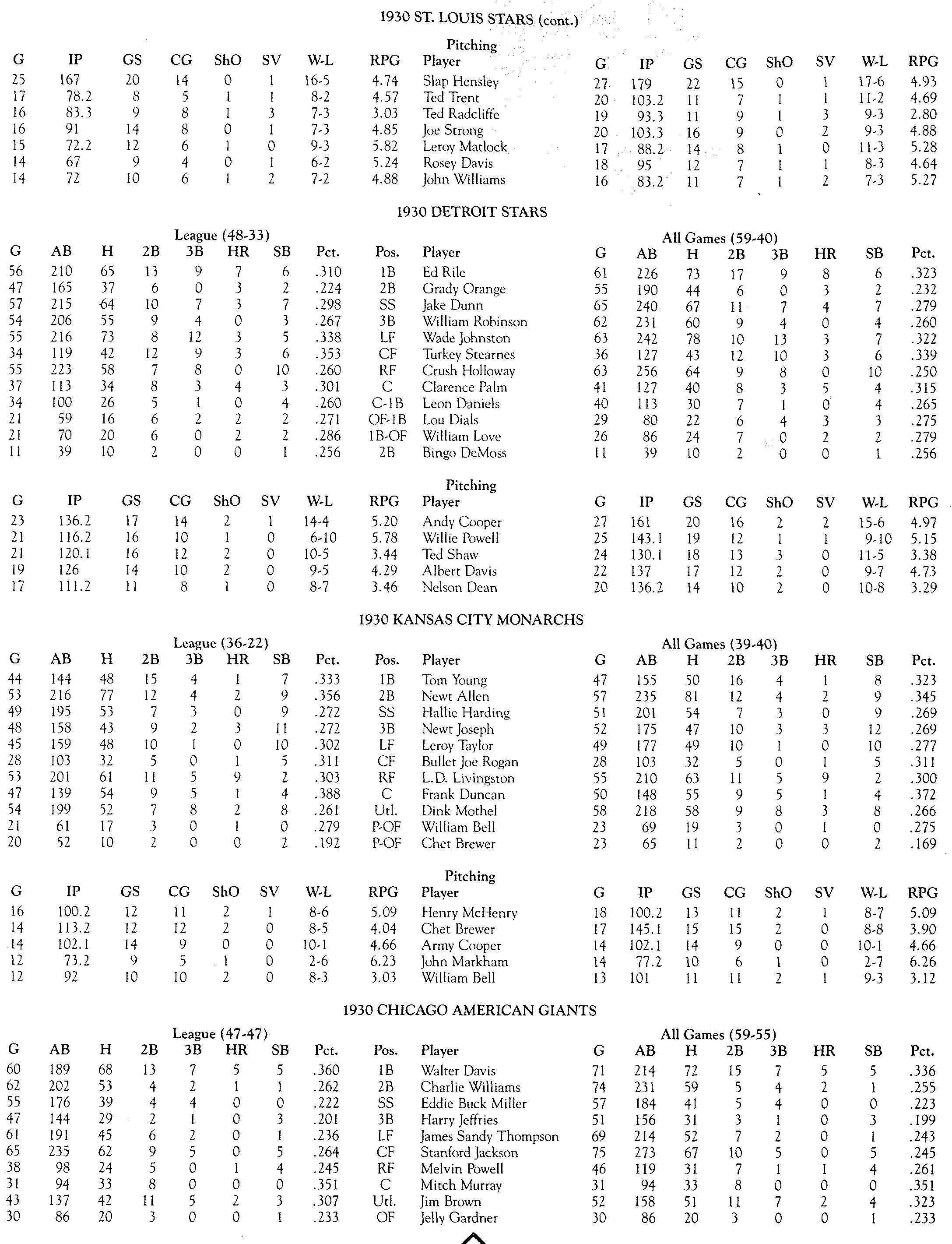

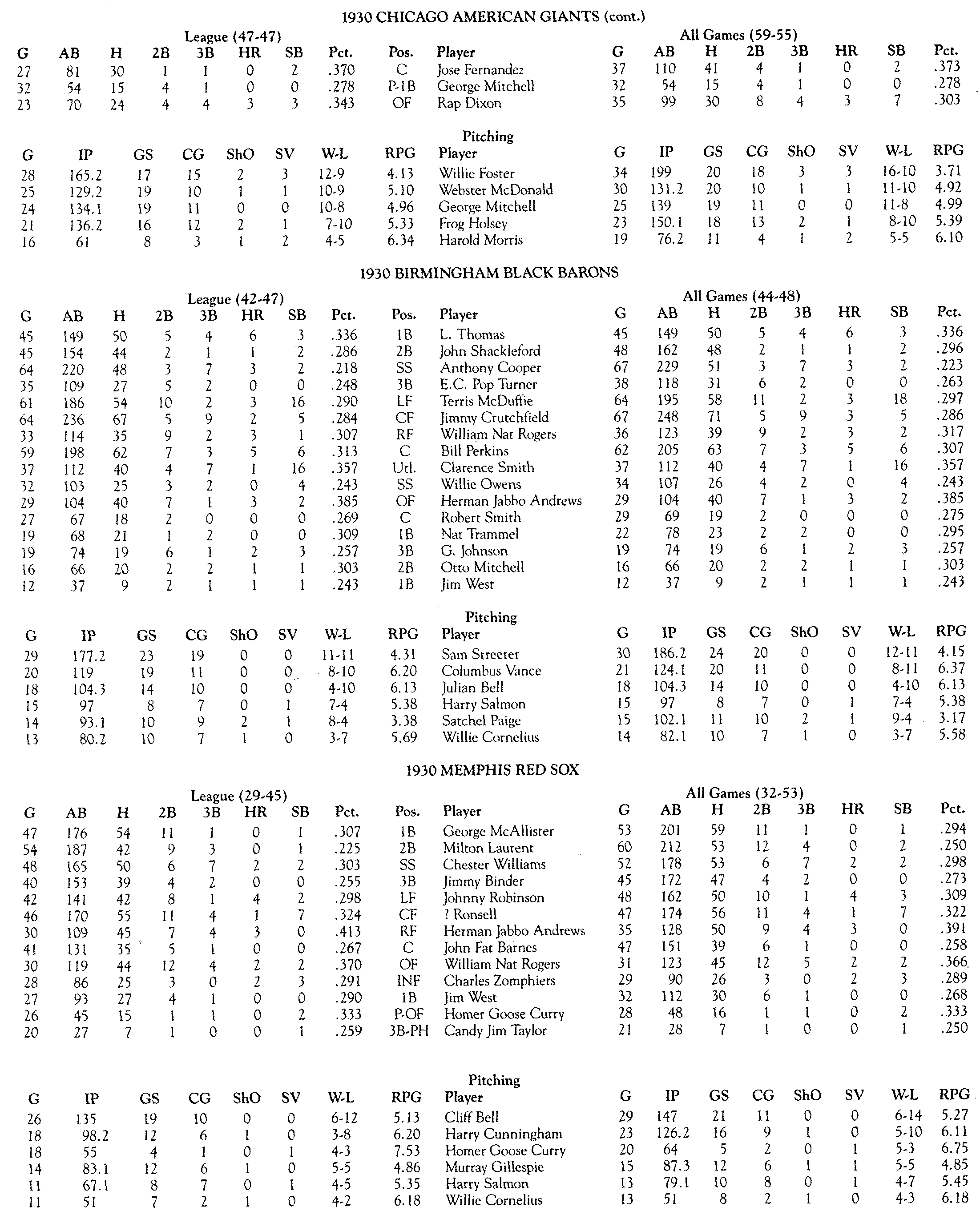

1930 Negro National League statistics

(Click images to enlarge)