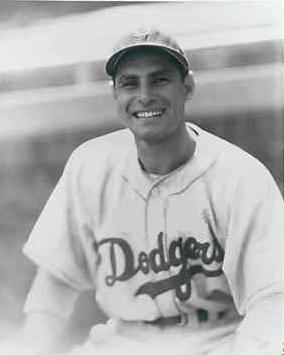

1947 Dodgers: Al Gionfriddo’s Memorable Game Six Catch

This article was written by Rory Costello

This article was published in 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers essays

In the bottom of the sixth inning of Game Six of the 1947 World Series, Al Gionfriddo replaced Eddie Miksis in left field. Normally an infielder, Miksis had gone in as a replacement for Gene Hermanski. As Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber later wrote, Brooklyn pitcher Joe Hatten was “wobbly.”[fn]Barber, Red. 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1984. p. 347.[/fn] After a sharp lineout, Snuffy Stirnweiss walked, Tommy Henrich barely missed a homer before fouling out, and Yogi Berra singled. Then Barber, on the Mutual radio network, called the moment that defined Gionfriddo for the rest of his life and beyond:

In the bottom of the sixth inning of Game Six of the 1947 World Series, Al Gionfriddo replaced Eddie Miksis in left field. Normally an infielder, Miksis had gone in as a replacement for Gene Hermanski. As Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber later wrote, Brooklyn pitcher Joe Hatten was “wobbly.”[fn]Barber, Red. 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1984. p. 347.[/fn] After a sharp lineout, Snuffy Stirnweiss walked, Tommy Henrich barely missed a homer before fouling out, and Yogi Berra singled. Then Barber, on the Mutual radio network, called the moment that defined Gionfriddo for the rest of his life and beyond:

“Joe DiMaggio up, holding that club down at the end. Big fellow sets, Hatten pitches—a curveball, high outside for ball one. Sooo, the Dodgers are ahead, 8–5. And the crowd well knows that with one swing of his bat this fellow’s capable of making it a brand-new game again. Outfield deep, around toward left, the infield over-shifted. Here’s the pitch, swung on—belted! It’s a long one deep into left center—back goes Gionfriddo! Back- back-back-back-back-back . . . he makes a one-handed catch against the bullpen! Ohhh-hooo, Doctor!”

Television, a World Series first that year, caught the iconic Yankee Clipper’s rare flicker of emotion as he kicked the dirt near second base. Joe D. was still miffed after the game. “‘Don’t write this in the paper,’ [DiMaggio] told a group of reporters, ‘but the truth is that if he had been playing me right, he would have made it look easy.’”[fn]Halberstam, David. Summer of ’49. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2002. p. 49. David Halberstam, age 13, was in the stands at Yankee Stadium that day. See Zant, John. “Gionfriddo’s Catch Receives the Stamp of Authority”. Santa Barbara Newsroom, May 11, 2007.[/fn] Gionfriddo himself later admitted that he was playing shallow, and a couple of steps over-shifted to left, at the direction of coach Clyde Sukeforth.[fn]Dave Anderson, “Subway Series Reflections: A Ride on the Carousel of Time,” The New York Times, October 20, 2000.[/fn] This heightened the drama of his sprint.

Al recounted the play many times over the years, most vividly in Roger Kahn’s book The Era 1947-1957. He described “Death Valley” in old Yankee Stadium, making the catch as a lefty, and getting a good jump. “‘I picked up DiMaggio’s ball good . . . I didn’t think I had a chance . . . I put my head down and I ran, my back was toward home plate and you know I had it right. I had the ball sighted just right.’ After all these years, Gionfriddo laughs in gorgeous triumph.”[fn]Kahn, Roger. The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002: p. 127.[/fn]

Al recounted the play many times over the years, most vividly in Roger Kahn’s book The Era 1947-1957. He described “Death Valley” in old Yankee Stadium, making the catch as a lefty, and getting a good jump. “‘I picked up DiMaggio’s ball good . . . I didn’t think I had a chance . . . I put my head down and I ran, my back was toward home plate and you know I had it right. I had the ball sighted just right.’ After all these years, Gionfriddo laughs in gorgeous triumph.”[fn]Kahn, Roger. The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002: p. 127.[/fn]

DiMaggio became more gracious about the play in later years. Talking with Al to a group of children, Joe said, “Some big guy wouldn’t have ever made the Catch. A big guy woulda backed off and left it to go over the fence. But this little guy. He always had to work harder than anybody else . . . he never gave up.”[fn]Ibid., p. 128.[/fn] DiMaggio and Gionfriddo also got together in 1974 to offer their recollections for the television program “The Way It Was.”[fn]Weichel, Penny. “Gionfriddo Revisited”. The Oil City (Pennsylvania) Derrick, November 16, 1974.[/fn]

Though most stories at the time said the ball would have been a home run, debate remains. Even then, it was not unanimous. Associated Press writer Frank Eck noted, “many in the [Yankees] dressing room believed the ball would have hit the iron fence for at least a triple.”[fn]Frank Eck, “DiMag’s Blow Called Longest He Ever Hit,” The Titusville (Pennsylvania) Herald, October 6, 1947.[/fn] DiMaggio biographer David Jones quoted historian Eric Enders: “This was merely an example of the halo granted DiMaggio by the New York media. Film of the play clearly shows that it would not have left the park. Indeed, Gionfriddo caught the ball two full steps in front of the fence.”[fn]Jones, David. Joe DiMaggio. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. pp. 97-98.[/fn], [fn]Enders, Eric.100 Years of the World Series. New York, NY: Barnes and Noble Books, 2003.p. 118.[/fn]

Al himself always thought he stopped it from going out. At the time, he told The Sporting News, “Bobby Bragan was in the bullpen, and he said it would have cleared the fence by from one to two feet.”[fn]Birtwell, Roger. “Little Al Didn’t Expect to Stay With Dodgers,” Sporting News, October 15, 1947.[/fn] On the radio, Red Barber (who was not given to hyperbole) said, “He took a home run away from DiMaggio.”

Visual evidence is questionable. Newsreel footage does not show the play from start to finish; there are even allegations it may be a staged re-enactment. However, an expert in the field, Doak Ewing, proprietor of Rare Sportsfilms, Inc., says, “Anybody who thinks that doesn’t know film. There are a couple of different views out there, with different angles, but how could you stage that crowd?” Sue Gionfriddo added, “Al had been asked, and he felt that the newsreel footage was accurate. It was always his understanding that it was live.”

Along with the fans’ reaction, reality shows in the way Gionfriddo loses his cap on the run and then gets it back from the center fielder (though one cannot make out Carl Furillo’s distinctive profile). The left-field umpire—the use of six umpires was another first from the ’47 Series—also enters the frame to give the “out” sign. Alas, umpire Jim Boyer passed away in 1959; his view is unknown.

Decades later, other authors have drawn and fostered (mis)impressions from this clip. For example, another DiMaggio biographer, Richard Ben Cramer, describes Al as “dancing a spirited tarantella, unsure where to run, which way to turn, how to get under the ball.”[fn]Cramer, Richard Ben. Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2000. p. 235.[/fn] Jonathan Eig called it a “stumbling, bumbling play.”[fn]Eig, Jonathan. Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2007. p. 257.[/fn] These descriptions belie Gionfriddo’s skill as an outfielder—and many other contemporary accounts. For one, Hall of Famer Bill Terry called it “the greatest catch I’ve ever seen.”[fn]“‘Greatest Catch I’ve Ever Seen’—Terry,” Winnipeg Free Press, October 6, 1947.[/fn]

Photographers got Pee Wee Reese to pose kissing Al on the cheek, though “finally Reese, grinning as happily as all the other Dodgers, pretended annoyance and called out: ‘Let somebody else kiss this little guy. I’m tired of it.’”[fn]Roscoe McGowen, “Outfielder Feted for Mighty Catch,” The New York Times. October 6, 1947.[/fn]

“I’ve signed thousands of that picture,” Gionfriddo remarked in 2000.[fn]Anderson, op. cit.[/fn] In 1991, he said, “You think, ‘Geez, how in the world do these people remember?’ They were there when they were teen-agers, I guess, and they tell their sons, their grandkids.”[fn]Campbell, Steve. “Gionfriddo’s Name Still Catchy Over 40 Years Later,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 11, 1991.[/fn] Hollywood portrayed this very thing in a tender deathbed scene from the 1989 film Dad with Jack Lemmon and Ted Danson.

Sue Gionfriddo recalled, “He used to say, ‘If all the people that said they were there that day actually were there, Yankee Stadium must have held a million.’”

RORY COSTELLO is the author of “Twilight at Ebbets Field” (The National Pastime #26), an essay of stadium lore revealing what happened after the Dodgers left Brooklyn. He is a longtime Brooklyn resident but was years too late to have the pleasure of seeing a game at the lovable old ballpark in Crown Heights.