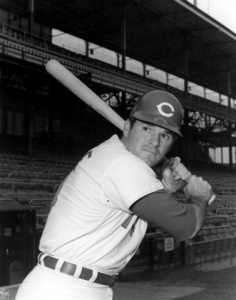

1975 Reds: Pete Rose mans the hot corner

This article was written by Rory Costello

This article was published in 1975 Cincinnati Reds essays

Pete Rose’s move from left field to third base in early May 1975 often receives credit as a pivotal moment in the success of the 1975 Reds — and with good reason. That’s when the team began to win consistently, surging to the National League West Division title.

Pete Rose roamed around the diamond during his 24 big-league seasons. Depending on when one saw him, the picture of Charlie Hustle with a glove on his hand varies. He was primarily a second baseman from 1963 through 1966. He shifted to the outfield in 1967, and played eight full seasons there through 1974 – even winning a pair of Gold Gloves in 1969 and 1970. During the final phase of his career, from 1979 through 1986, he was a first baseman.

Pete Rose roamed around the diamond during his 24 big-league seasons. Depending on when one saw him, the picture of Charlie Hustle with a glove on his hand varies. He was primarily a second baseman from 1963 through 1966. He shifted to the outfield in 1967, and played eight full seasons there through 1974 – even winning a pair of Gold Gloves in 1969 and 1970. During the final phase of his career, from 1979 through 1986, he was a first baseman.

Yet Rose also played third base in about 18 percent of his games – chiefly from 1975 through 1978. His move from left field to third base in early May 1975 often receives credit as a pivotal moment in the success of the 1975 Reds — and with good reason. The batting order became much more potent because Rose continued to set the table and George Foster soon took over left field. Also, keeping Rose’s bat in the lineup over light-hitting utility types John Vukovich, Doug Flynn, and Darrel Chaney did not come at a cost in defense. As Rose emphasized to sportswriter Joe Posnanski for a July 2009 article in Cincinnati magazine, “I wasn’t a great third baseman. But I worked my ass off. I don’t know if people realize how hard I worked.”1

And quite simply, the team began to win consistently. When Rose made his first start at the hot corner on May 3, 1975, Cincinnati was playing only .500 ball (12-12). The rest of the way, the Reds went 96-42 (.696).

There was a good bit of history behind the move. Third base had been an unsettled spot for Cincinnati during the mid-1960s. In fact, Rose had gotten a brief trial there at the beginning of the 1966 season, and it didn’t work out. From 1967 through 1971, Tony Pérez played at third, out of his natural position. That move as well was enabled by Rose’s switch from second base to left field. Pérez shifted to first base in 1972 after the blockbuster November 1971 trade with Houston, in which (among several other players) the Reds obtained infielder Denis Menke and dealt away slugging first baseman Lee May. Menke hit a combined .218 during his two seasons as the primary starter at third base, though, and so he was shipped back to the Astros for pitcher Pat Darcy.

In 1974 the team stuck Dan Driessen’s bat at third base. A natural first baseman, he was rocky with the glove at third (.915 fielding percentage at that position in 122 starts). Catcher Johnny Bench also started 30 games there, and various other players accounted for the remaining 10.

General manager Bob Howsam did not view Driessen as a viable ongoing option – in fact, he never appeared at third base again during his remaining 13 seasons in the majors. That December, The Sporting News ran an article called “Howsam Sees Safety in Numbers at Hot Sack.” The GM mentioned four players who could compete for the third-base job in 1975:

- Arturo DeFreites: This young Dominican eventually played 32 games for the Reds in 1978 and 1979. In that brief big-league career, he was mainly a pinch-hitter, playing a bit at first base and in the outfield – but not at third (his part-time position in the minors).

- Joel Youngblood: Cincinnati’s second-round draft pick in 1970, Youngblood went on to a 14-year career in the majors, mainly in the outfield. When the San Francisco Giants put him at third base regularly in 1984, his fielding percentage was an abysmal .887.

- Ray Knight: Knight, a tenth-round pick in 1970, was a very good true third baseman who had gotten his first major-league trial in 1974. He remained in the minors in 1975-76 but eventually took over at third base with Cincinnati in 1979 after Rose left the Reds via free agency. Knight later won a championship and was the World Series MVP with the New York Mets in 1986.

- John Vukovich: The Reds obtained this utilityman in an October 1974 trade. The article said, “While Vukovich has an outstanding glove, his bat is suspect.”2

Before spring training in 1975, according to Reds beat writer Earl Lawson, “listening to Howsam, one gathers that DeFreites rates as the No. 1 candidate among the youngsters.” Darrel Chaney, mainly a shortstop, was also in the mix.3 Sparky Anderson told Vukovich, “The third base job is wide open.”4 Vukovich got the opportunity, based largely on his defensive ability, and though there was talk of a platoon, he started most of the games at third base in April.

As had been feared, though – despite expressions of confidence from the brass in the off-season – Vukovich didn’t hit. In fact, as Joe Posnanski described at length in his 2009 book The Machine, Anderson hung the derisive nickname Balsa on him for his soft bat.5 Chaney and Flynn got some starts, but the three players were hitting a collective .157 (14 for 89) on May 2 when the exasperated Anderson felt he had to make a move to secure more offensive production from his lineup.

Posnanski also provided much colorful inside detail on various other aspects of the situation. There was how Anderson asserted his authority over the team, as seen in his handling of Vukovich. There was the flash of inspiration that spurred Sparky to try Rose at third. But above all, there was the psychology involved. When Cincinnati’s manager in 1966, Don Heffner, had moved Rose, it was an order. Anderson didn’t tell, he asked.6 Appealing to Rose’s desire to help the team made it happen (though when the Hit King was chasing Ty Cobb’s record as playing manager in 1985, another motive was visible).

Previous insight came from John Erardi and Greg Rhodes, who wrote The Big Red Dynasty (1997). They noted that Anderson also had to find playing time for his many well-qualified outfielders and Dan Driessen – and that preserving his own job was also a part of moving Rose. Howsam, who was away in Arizona, thought it was a mistake when he saw the box score of the May 3 game – and said “Oh my God” when he found out it was for real. Reds broadcaster Marty Brennaman talked about Rose’s initial adventures in the field. The book also recounted how Rose’s teammates “were all over him”7 for his unpolished play.

As a United Press International feature described it that July, “Pete Rose plays third base like a mad bull. He barricades the ball, stomps after it, or hurls himself in its vicinity, whatever he feels it takes to catch, stop or somehow slow down the ball. … ‘Finesse!’ he shouts. ‘I don’t play with finesse. Aggressive. That’s what I am. That’s the way I play third base.’ ”8

Further quotes were entirely in character. “I love to play third. You know why? ’Cause I get to touch the ball after each out. … Third base is more fun than the outfield. I feel more a part of the game. Closer to it.” He made the same point that he did to Posnanski more than 30 years later: “Hard work. I work hard, that’s it. I think if you work hard enough you can do just about anything, or come close to it. I may not look too smooth out there, but I’m working, I’m getting the job done.”9

Rose committed just 13 errors in 349 chances at third in 1975, a respectable .963 fielding percentage. When asked that July if hitters were able to bunt on him, the reply was again as one would expect. “‘Yeah, three or four have tried it,’ says Rose with a hard, straight face. The subject is serious to him. ‘But I threw ’em out. No problem.’”10 Fielding in the postseason wasn’t a problem either, as he cleanly handled all the relatively few chances that came his way.

In his 2004 biography, Pete Rose: Baseball’s All-Time Hit King, author William Cook noted another important dimension of the move. “[Rose] remarked that the advantage it gave the Reds, other than getting the powerful bat of George Foster into the lineup, was that it gave the Reds a set lineup to play every day. Sparky Anderson agreed with that assessment, stating that after he moved Rose to third and inserted Foster in left he concerned himself mainly with the Reds’ pitching and hardly paid any attention to the starting eight for the rest of the season.”11

Rose started an average of 157 games a year at third with the Reds from 1976 through 1978. There was precious little time for his backups, first Bob Bailey and later Ray Knight. After the 1978 season, Rose signed with the Philadelphia Phillies. He shifted to first base for the Phillies – reflecting the presence of Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt at third. Rose returned to the outfield with some frequency in 1983 and again in 1984, by which time he was with Montreal. However, he played only five more games at third (all in 1979).

Nonetheless, Pete Rose’s years at the hot corner formed a vital chapter in his career. If this move hadn’t taken place, perhaps the Los Angeles Dodgers might have won the NL West – and the pennant – for five straight years. In that case, nobody would have written books about the Reds dynasty.

Notes

1 Joe Posnanski, “The Hit King’s Lament,” Cincinnati, July 2009, 71.

2 Earl Lawson, “Howsam Sees Safety in Numbers at Hot Sack,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1974, 54.

3 Earl Lawson, “Hot Corner Will Be Crowded When Reds Open Camp,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1975, 43.

4 Earl Lawson, “Sparky to Give Reds Rfesher in Fundamentals,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1975, 36.

5 Joe Posnanski, The Machine (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 26-28.

6 Posnanski, The Machine, 75, 89.

7 John Erardi and Greg Rhodes, The Big Red Dynasty (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1997).

8 “Pete Rose Hot at Third Base,” United Press International, July 20, 1975.

9 “Pete Rose Hot at Third Base.”

10 “Pete Rose Hot at Third Base.”

11 William A. Cook, Pete Rose: Baseball’s All-Time Hit King (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2004), 46-47.