An Ever-Changing Story: Exposition and Analysis of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s Public Statements on the Black Sox Scandal

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in Spring 2019 Baseball Research Journal

When it came to his involvement in the corruption of the 1919 World Series, Shoeless Joe Jackson rarely told the same story twice. When the fix first came to light in late September 1920, Jackson, along with teammates Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams, abjectly admitted that he had agreed to join the conspiracy to throw the series in return for a gamblers’ payoff. And that he had accepted $5,000 of a promised $20,000 bribe before the start of Game Five. But once in the hands of experienced legal counsel, Jackson’s story changed.

When it came to his involvement in the corruption of the 1919 World Series, Shoeless Joe Jackson rarely told the same story twice. When the fix first came to light in late September 1920, Jackson, along with teammates Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams, abjectly admitted that he had agreed to join the conspiracy to throw the series in return for a gamblers’ payoff. And that he had accepted $5,000 of a promised $20,000 bribe before the start of Game Five. But once in the hands of experienced legal counsel, Jackson’s story changed.

From then on, Jackson was the injured innocent, unaware that teammates had tried to rig the series outcome until after the fact, and entirely blameless in the affair. Even here, however, Jackson had trouble keeping the details of his story straight. His appearance on the witness stand in support of a civil lawsuit that he filed against the White Sox ended in disaster. Jackson was cited for contempt by the trial judge and subsequently charged with perjury by the Milwaukee County District Attorney. That charge ultimately went unprosecuted, and Jackson was still protesting his innocence at the time of his death in December 1951.

The text below examines the evolution of Joe Jackson’s public statements on the Black Sox Scandal. A forensic examination of those statements follows. We precede that exposition with a brief, Jackson-centric recap of the 1919 World Series and its aftermath.

THE 1919 WORLD SERIES AND EARLY INQUIRIES ABOUT CROOKED PLAY

The talent-laden Chicago White Sox were the Series betting favorites until a late surge of Cincinnati money gave the Reds a slight edge. Still, the Sox remained the choice of most sportswriters and other baseball insiders. But Chicago got off poorly in Game One when a sudden fourth-inning meltdown by pitching ace Cicotte triggered a lopsided 9–1 defeat. Then, a curious one-inning control lapse by 23-game winner Williams proved the difference in a 4–2 Game Two loss. A three-hit, 3-0 shutout thrown by undersized Dickey Kerr temporarily righted the Sox in Game Three, but Chicago bats thereupon went silent. The American League’s best hitting team went an astonishing 26-consecutive innings without scoring.1 Shutout defeats in Games Four and Five left the vaunted Sox on the brink of elimination just midway through the extended best-five-of-nine series.

Although hardly without accomplices in underachievement, a fair amount of the blame for the Sox predicament rested with clean-up hitter Joe Jackson. Through the first five games, Shoeless Joe had batted a soft .316 (6-for-19), with two runs scored and zero RBIs. Down 4–0 after four innings in Game Six, Chicago bats suddenly revived. A Jackson single in the sixth plated the first run, and the Sox went on to post a 10-inning, 5–4 victory. Thereafter, Eddie Cicotte put the Sox back in contention with a route-going 4–1 triumph which featured two more RBIs by Jackson. In Game Eight, however, a nightmarish outing by Lefty Williams — he did not survive the first inning — quickly put the Sox in a deep hole. With Chicago trailing 5–0, Jackson hit a solo home run in the bottom of the third. But Cincinnati kept up the attack against Sox relievers, and held a seemingly insurmountable eighth-inning 10–1 lead when a last-ditch Chicago rally cut the margin to 10–5. Two of those Sox runs were tallied by a Jackson double that upped his series RBI total to six. In their final at-bat, Chicago attempted another rally. But with two on and two out, a Jackson grounder to second brought the 1919 World Series to a close.

- Related link: Check out SABR’s Eight Myths Out project to learn more about common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

A day after the World Series ended, a widely syndicated column by Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton insinuated, without explicitly saying, that the Series had not been played on the up-and-up. But otherwise, the Cincinnati triumph, while unexpected by most, was well-received. Those seeking culprits for the Sox downfall did not focus on Joe Jackson. Superficially at least, his Series stats (.375 batting average, with a club-high six RBIs and the championship’s only homer) were considered outstanding. Blame for the Sox defeat was more readily pinned on Lefty Williams (0–3, with a 6.61 ERA), shortstop Swede Risberg (.080 BA in 25 at-bats, with four errors in the field), right fielder Nemo Leibold (.056 BA in 18 at-bats), and manager Kid Gleason.

Unbeknownst to the public, the Series outcome was not accepted at face value by two of the game’s most powerful actors: Chicago White Sox club owner Charles Comiskey and American League president Ban Johnson. Shortly after the Series conclusion, each began his own discreet inquiry into the series bona fides. And neither much liked what such probes uncovered. Information furnished to Comiskey investigators by St. Louis sources lent substance to the report — first received by Comiskey just after the series began — that Sox players had agreed to dump the series in return for a payoff from gamblers. In late December, these fix assertions were repeated by in-the-know gamblers Harry Redmon and Joe Pesch during a face-to-face meeting with White Sox brass. Notwithstanding that, Comiskey subsequently extended handsome new contract offers to players implicated in the fix by his informants: Joe Jackson, Swede Risberg, Lefty Williams, and outfielder Happy Felsch.2 Ban Johnson, meanwhile, had uncovered independent evidence that Sox players had been corrupted, purportedly bribed by a St. Louis businessman-gambler named Carl Zork. For the time being, however, Johnson chose not to make such revelations public.

While scandal simmered quietly out of public view, American League rooters focused on a tight three-way 1920 pennant chase involving the White Sox, New York Yankees, and Cleveland Indians. But early that September, fan attention was mildly diverted by the announcement that a Cook County (Chicago) grand jury had been impaneled to probe allegations that a recent Cubs-Phillies game had been fixed. The grand jurors would also investigate the locally popular but illegal practice of baseball game pool selling. Soon thereafter, prominent Chicago citizen Fred Loomis and sports reporters like Joe Vila of the New York Sun were publicly calling for the grand jury probe to be expanded to include inquiry into the integrity of the 1919 World Series.3 Behind the scenes, AL president Johnson was urging the same course upon a longtime acquaintance, Judge Charles A. McDonald, the presiding judge of the Chicago criminal courts and the overseer of the grand jury. Judge McDonald was agreeable, and within weeks the 1919 World Series became the dominant subject of the grand jury’s work.

EXPOSURE AND ADMISSION

In an extraordinary breach of normal secrecy requirements, the grand jury proceedings were publicly revealed on a daily basis, with many newspapers printing near-verbatim accounts of witness testimony. Thus by September 25, it was widely reported that eight White Sox players, including Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams, had been targeted for indictment by the grand jury on conspiracy and fraud-related charges grounded in their play in the 1919 World Series.4 Two days later, the burgeoning scandal exploded. In an interview first published in Philadelphia and then circulated nationwide, self-admitted fix insider Billy Maharg alleged that Game One, Game Two, and Game Eight of the Series had been dumped by the Sox at gamblers’ behest.5

The following morning, Eddie Cicotte was summoned to the law office of Alfred S. Austrian, counsel for the Chicago White Sox corporation. Under interrogation, a stressed-out Cicotte quickly broke down, revealing those aspects of the World Series fix that he was privy to. He also identified the other fix participants, including Joe Jackson.6 Cicotte was then whisked before the grand jury where he elaborated on his admissions about the Series conspiracy under questioning by Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle.7

The first public statement attributed to Joe Jackson about the fix allegations disclaimed any personal knowledge of the matter. “I am willing to go before anyone at any time, any place to testify to what I know. I know little except rumors,” said Joe early that morning. “I know I have never been approached with any gambling propositions. If anyone ever does approach me, I’ll knock their block off.”8

Jackson soon got his wish to testify. After being confronted privately with Cicotte’s admissions in the Austrian law office, Jackson telephoned the chambers of Judge McDonald. At first, Jackson maintained his innocence to an openly skeptical McDonald. During a second call placed shortly thereafter, Jackson asked the judge for the chance to appear before the grand jury and make a clean breast of his involvement in the World Series fix.

Neither the content of Jackson’s telephone conversations with Judge McDonald nor the particulars of their subsequent conversation in chambers was contemporaneously memorialized. But testifying four years later during Jackson’s civil suit against the White Sox, McDonald stated that Jackson related various fix details to him, and identified his co-conspirators as Eddie Cicotte, Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, Lefty Williams, Happy Felsch, Buck Weaver, and Fred McMullin.9 In particular, McDonald “distinctly” recalled that Jackson told him that during the Series “he had made no misplays that could be noticed by the ordinary person, but that he did not play his best.”10

On the afternoon of September 28, 1920, Jackson testified under oath before the grand jury. At the core of the Jackson testimony rests a contradiction. On the incriminating side of the ledger, Jackson provided a fairly detailed account of the fix from his perspective, including his acceptance of $5,000 before the start of Game Five. Notwithstanding that, Jackson insisted that he had done nothing in the field to earn his payoff, citing his World Series stats as proof that he had given his best efforts at all times during the action.

Jackson’s testimony about the corruption of the World Series was precise and specific. He had not attended the mid-September players-only fix meeting at the Ansonia Hotel in New York. Nor had he been present for a follow-up meeting with gamblers in Chicago’s Warner Hotel, although Lefty Williams had told him about it afterwards.11 Rather, Jackson had been propositioned privately by teammate Chick Gandil. At first, Jackson rebuffed him. But in time, Joe agreed to join the plot to throw the Series in return for a $20,000 payoff, to be “split up some way” after each series game.12, 13 When he went unpaid after the Sox lost Game One, Jackson asked Gandil, “What’s the trouble?” but Gandil assured him that “everything is all right,” as Gandil had the money. Then, Jackson testified, “We went ahead and threw the second game,” only to be unpaid again. Jackson now asked Gandil, “What are you going to do?” and Gandil replied, “Everything is all right” once more.14 When no money was forthcoming after Game Three, Jackson told Gandil that “somebody is getting a nice little jazz, everything is crossed.” But Gandil responded that the fault lay with fix backers Abe Attell and Bill Burns. The two gamblers had crossed him.15

On the evening before the White Sox were to return to Cincinnati for Game Five, Lefty Williams entered Jackson’s room at the Lexington Hotel and threw $5,000 onto the bed. At that, Jackson asked, “What the hell had come off here?” Williams replied that Gandil “said we got the screw through Abe Attell. He got the money but refused to turn it over to [Gandil].” But Jackson suspected that Gandil actually had the payoff money and had “kept the majority of it for himself.”16 When Jackson later complained to Gandil, Chick told him that he could either “take that [$5,000] or leave it alone.”17 That evening, when Jackson told his wife that he “got $5,000 for helping throw [Series] games,” Katie Jackson told Joe that “she thought it was an awful thing to do.”18 Jackson put the $5,000 — “some hundreds, mostly fifties” in denomination — in his pocket and took the money with him to Cincinnati.19

Regarding the other conspirators, Jackson testified that Cicotte had told him that he had received $10,000 up front, and scolded Joe as “a God damn fool” for not getting paid the same way.”20 Risberg and Williams told Jackson that they received $5,000 each, but Jackson did not believe them. He suspected that Gandil, Risberg, McMullin, Cicotte, and Williams had cut up the bribe money “to suit themselves.”21 Jackson understood from “the boys” that Happy Felsch had also received $5,000, but had no knowledge of any payoff money paid to Buck Weaver.22 All Jackson knew about Buck was that Gandil had told him that Weaver “was in on the deal.”23

Despite having agreed to the fix and then accepting a payoff, Jackson nevertheless insisted that he had done nothing on the field to earn the money. Throughout the series, he “had batted to win, fielded to win, and run the bases to win.”24 Joe admitted that while he saw some questionable plays by teammates, particularly Cicotte and Williams, Jackson himself had not done anything to throw World Series games. He had “tried to win all the time.”25 After the Series was over, Jackson did not discuss the fix with his co-conspirators, and left Chicago for his home in Savannah the following evening.26 Jackson was ashamed of himself for accepting the $5,000, and had offered to reveal everything that he knew about the fix to White Sox management later that fall. But club brass had not brought him in.27

Jackson was also suspicious of late-1920 season performances by Cicotte and Williams, but declared himself anxious to win the pennant and then capture the World Series.28 This led to a poignant exchange near the end of the Jackson testimony. ASA Replogle: “You didn’t want to do that last year, did you?” Jackson: “Well, down in my heart I did. Yes.”29 Shortly thereafter, the grand jury proceedings recessed for the day.

Upon leaving the courthouse, Jackson was besieged by waiting reporters. Back in his hotel room later that evening, Jackson expounded upon various fix details. For example, following telephone calls that he had placed to an unsympathetic Judge McDonald, Jackson had gone to the jurist’s chambers. Once there, “I said I got $5,000 and they promised me $20,000. All I got was the $5,000 that Lefty Williams handed me in a dirty envelope. I never got the other $15,000. I told that to Judge McDonald. He said he didn’t care what I got. … I don’t think the judge likes me. I never got the $15,000 that was coming to me,” said Joe.30

Jackson further explained that his grand jury revelations were prompted by the attitude of Gandil, Risberg, and McMullin. When he had threatened to expose the series fix unless paid in full, Jackson was brushed off. “They said to me, ‘You poor simp, go ahead and squawk. … Every honest ballplayer in the world will say you’re a liar. You’re out of luck. Some of the boys were promised a lot more than you and got less.’ That’s why I went down and told Judge McDonald and told the grand jury what I know about the frame up,” Jackson told the press.31

Jackson concluded his extemporaneous monologue with this revelation: “And I’m going to give you a tip. A lot of these sporting writers that have been roasting me have been talking about the third game of the World’s Series being square. Let me tell you something. The eight of us did our best to kick it and little Dick Kerr won the game by his pitching. Because he won it, those gamblers double crossed us because we double crossed them.”32

The following day, Lefty Williams confessed his involvement in the Series fix, first in the Austrian law office, thereafter before the grand jury. In the process, Williams named Jackson as one of the eight Sox players who had been in on the deal.33 Williams also identified several of the gamblers who had agreed to finance the fix. The next day, the Chicago Evening American published a confession of fix participation given by Sox center fielder Happy Felsch to reporter Harry Reutlinger. Felsch now regretted his acceptance of a $5,000 bribe, but offered no excuses for his involvement. “I’m as guilty as the rest of them. We are all in it alike,” said an unhappy Happy. “Cicotte’s story is true in every detail,” Felsch continued. “I don’t blame him for telling. … I was ready to confess myself yesterday, but didn’t have the courage to be the first to tell.”34

Meanwhile, the other White Sox players who had been cited as grand jury targets publicly protested their innocence, with Buck Weaver in particular vowing to retain the best lawyer available to fight any criminal charges that might be brought against him.35 Buck would not have to wait long for such charges. On October 29, 1920, the Cook County Grand Jury returned formal indictments which accused eight White Sox players and five gamblers of multiple counts of conspiracy to obtain money by false pretenses and/or a confidence game.36

Shoeless Joe Jackson, right, and Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle pose together during Jackson’s grand jury appearance on September 28, 1920, in Chicago. (COURTESY OF BLACKBETSY.COM)

A NEW-FOUND CLAIM OF INNOCENCE

It appears that Cook County prosecutors presumed that those White Sox players who had confessed their fix involvement to the grand jury would turn State’s evidence and testify against the other accused. But pretrial negotiations with Daniel Cassidy, the Detroit lawyer (and personal friend) who represented Eddie Cicotte, foundered, while Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams were reportedly seeking legal counsel to fight the charges. Out in California meanwhile, Fred McMullin asserted that Happy Felsch had told him that his newspaper confession was a “phony.”37 Days later, Joe Jackson signaled a coming change in his story, publicly declaring, “I never confessed to throwing a ball game and I never will.”38 This evidently proved too much for Judge McDonald, who promptly informed the press that “Jackson’s testimony was made under oath to the grand jury. If he denies that testimony when he is brought to trial, he will be guilty of perjury and prosecuted under that charge.”39

In early November, developments in the baseball scandal were briefly overshadowed by an event of far greater national significance: the political elections of 1920. But election results would also have profound effects upon the course of the Black Sox case. Swept into office on the nationwide Republican Party tide was a new Cook County State’s Attorney, recently retired Chicago judge Robert E. Crowe. And joining Crowe in office would be an entirely new cadre of staff attorneys, none of whom was familiar with the Black Sox case. As a team of prosecutors headed by newly installed Second ASA George E. Gorman scrambled to catch up, the Black Sox defense made its first tactical move: a court application which included sworn repudiation of their grand jury admissions by Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams.

Drafted by criminal counsel Thomas D. Nash (defendants Weaver, Felsch, Risberg, and McMullin) and Benedict J. Short (Jackson and Williams), a defense motion for a bill of particulars was supported by affidavits signed by Buck Weaver, Jackson, and Williams.40 The bill of particulars averred that (1) while acquainted with gambler codefendants Bill Burns and Hal Chase, they had “no business transactions or personal relations” with the two ex-major leaguers; (2) that they had never met the other gambler codefendants (although Williams had once been introduced to strangers named Sullivan and Brown);41 and (3) that they were “entirely innocent” of the charges made against them.”42 When it came time for trial in July 1921, however, neither Weaver, Jackson, nor Williams testified before the jury.43 Nor did any of the other accused players.44 But out of the jury’s presence, Eddie Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams did take the stand mid-trial in support of a defense motion to preclude prosecution use of their grand jury testimony. Significant for our purposes, the Black Sox defense did not challenge the bona fides of the grand jury transcripts, nor claim that any of their content was inaccurate or unreliable. Indeed, the authenticity and correctness of the transcripts was conceded. Rather, the defense sought suppression on the grounds that the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony had been induced by broken off-the-record promises of non-prosecution made by authorities, and were thus inadmissible in evidence.45

At the hearing’s close, trial judge Hugo M. Friend found the denials that any such promises had been made elicited from former ASA Replogle and Judge McDonald persuasive, and ruled the Cicotte/Jackson/Williams transcripts available for prosecution use. In redacted form, the grand jury admissions of the trio were subsequently read to the criminal trial jury at length via colloquy between Special Prosecutor Edward A. Prindiville and grand jury stenographers Walter Smith and Elbert Allen — all to no avail as it turned out.46

Silence proved a sound defense strategy, as the jury acquitted the accused of all charges after deliberations taking less than three hours.47 Public reaction to the trial’s outcome for those acquitted was subdued, but the Black Sox case was far from over. Within hours of the verdict, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis permanently banished the accused players from Organized Baseball, their acquittal in court notwithstanding. Thereafter, a number of the former defendants, including Joe Jackson, instituted civil lawsuits against the Chicago White Sox.48

The particulars of a new Jackson account of the World Series fix emerged during the deposition phase of his lawsuit. And the story now told by Jackson was dramatically different from the sworn testimony that he had provided the grand jury in late September 1920. Appearing before court commissioner Girard M. Cohen on April 23, 1923, Jackson swore that “I knew absolutely nothing about the throwing of the World Series until two or three days after it was over.”49 Jackson further averred that “I played my best during the Series, threw everything that I had into the effort to bring victory to my team. I think the facts and figures [of my performance] will bear me out.”50

Regarding his acceptance of fix-connected cash, Jackson revised the timing of that event. He now asserted that “two or three days after the Series was over, Lefty Williams … came to my room with two envelopes in his hand. Williams was in an intoxicated condition. He told me that each envelope contained $5,000 in cash. He threw one of the envelopes at my feet and told me that certain players had used my name in negotiating with the gamblers and that the players had informed the gamblers that I was to help throw the games against my own team.”51 Jackson maintained that he was “dumbfounded” by Williams’s revelations and immediately informed him that “they had a lot of nerve to use my name under the circumstances.”52 Lefty then departed the room. “The very next day,” Jackson continued, “I went to Charles Comiskey’s office with the envelope to interview the club president concerning the transaction with Williams,” but was denied admittance by White Sox team secretary Harry Grabiner, who told Jackson “to beat it.” When he came to Savannah the following February to sign Jackson to a new contract, Grabiner already knew about the $5,000 given Jackson by Williams, and told him that White Sox brass had “the absolute goods on Cicotte, Williams and Gandil concerning their dishonest and crooked play during the 1919 Series.”53 Jackson then signed the new three-year contact proffered by Grabiner, the terms of which would subsequently become the gravamen of the civil lawsuit filed by Jackson against the club.

MILWAUKEE PERJURY CITATIONS

Of the Black Sox-related civil lawsuits filed in Milwaukee, the only one that ever went to trial was that of Joe Jackson. The specifics of that litigation are not germane to this article. Suffice it to say that Jackson sought recovery of the unpaid portion of the three-season deal that he had signed with the White Sox in February 1920.54 At first blush, the setting seemed a congenial one for the plaintiff. His attorney, local firebrand Raymond J. Cannon, was an aggressive and wildly successful civil litigator, having reportedly won over 100 cases in a row.55 The Jackson case, moreover, would be tried before Wisconsin Circuit Court Judge John J. Gregory, a competent and amiable veteran jurist, progressive in his social views (except in divorce matters) and widely perceived as plaintiff-friendly. Gregory was also an avid baseball fan. But before the trial was out, the proceedings would turn into a nightmare for Joe Jackson.

Of the Black Sox-related civil lawsuits filed in Milwaukee, the only one that ever went to trial was that of Joe Jackson. The specifics of that litigation are not germane to this article. Suffice it to say that Jackson sought recovery of the unpaid portion of the three-season deal that he had signed with the White Sox in February 1920.54 At first blush, the setting seemed a congenial one for the plaintiff. His attorney, local firebrand Raymond J. Cannon, was an aggressive and wildly successful civil litigator, having reportedly won over 100 cases in a row.55 The Jackson case, moreover, would be tried before Wisconsin Circuit Court Judge John J. Gregory, a competent and amiable veteran jurist, progressive in his social views (except in divorce matters) and widely perceived as plaintiff-friendly. Gregory was also an avid baseball fan. But before the trial was out, the proceedings would turn into a nightmare for Joe Jackson.

Things began well for the plaintiff, with Jackson’s direct examination by attorney Cannon drawing favorable press reviews.56 The tide abruptly turned, however, when Jackson underwent cross-examination by George B. Hudnall, lead attorney for the White Sox defense. Hudnall was armed with the transcript of Jackson’s September 28, 1920, grand jury testimony.57 He pressed the plaintiff on the inconsistencies between his current account of scandal events and what he had previously told the Cook County grand jury. Remarkably, Jackson did not attempt to harmonize the two or explain away their differences. Instead, he asserted that he had never said the words reposed in black and white on the grand jury transcript pages.

As Cannon sat by helplessly, Hudnall then led Jackson on a painstaking tour of the testimony that Jackson now maintained he had never given. Page space limitations preclude a thorough rendering of the Hudnall-Jackson colloquies, but the following are representative: When referred to his grand jury testimony that the World Series fixers had “promised me $20,000 and paid me $5,000 (at JGJ4-9 to 10),” Jackson told Hudnall, “I didn’t make that answer.”58 When asked about what Chick Gandil had said to him about the fix payment shortchange (at JGJ6-10 to 13), Jackson’s response was the same. He denied giving the testimony attributed to him in the grand jury transcript.59 Thereafter, Hudnall: “Were you asked and did you give this answer? Question: What did you say to Williams when he threw down the $5,000? Answer: I asked him what the hell had come off here (quoting JGJ6-25 to JGJ7-5).” Jackson: “No, sir. I don’t know anything about that.” Hudnall: “And you did not so testify before the grand jury?” Jackson: “No, sir. I didn’t.”60 Similarly, when referred to his grand jury testimony about the “jazz” given the players by fixer Abe Attell, Jackson denied the authenticity of the response reported at JGJ9-10 to 13. Hudnall: “You didn’t make any such answer before the grand jury?’ Jackson: “No, sir.”61

Elsewhere, Jackson again denied that he had given the answers contained in the grand jury transcript about his acceptance of the money delivered by Williams before Game Five. Insisted Jackson, “I didn’t make the answer like you are reading from there. No, sir.”62 Regarding his grand jury testimony about the $10,000 bribe paid Eddie Cicotte, Jackson replied, “I say that I did not make the answer that you read there.”63 Nor had Jackson testified about fix payments to Swede Risberg and Fred McMullin during his grand jury appearance. Hudnall, incredulously: “Those questions were not asked and you did not make those answers?” Jackson: “No, sir.”64 Also repudiated by Jackson were transcript excerpts pertaining to pre-Series conversations with Gandil, fix payments to Happy Felsch, Katie Jackson’s reaction to Joe’s involvement in the fix, and, by this writer’s count, 119 other particulars of Jackson’s sworn grand jury testimony.65, 66, 67

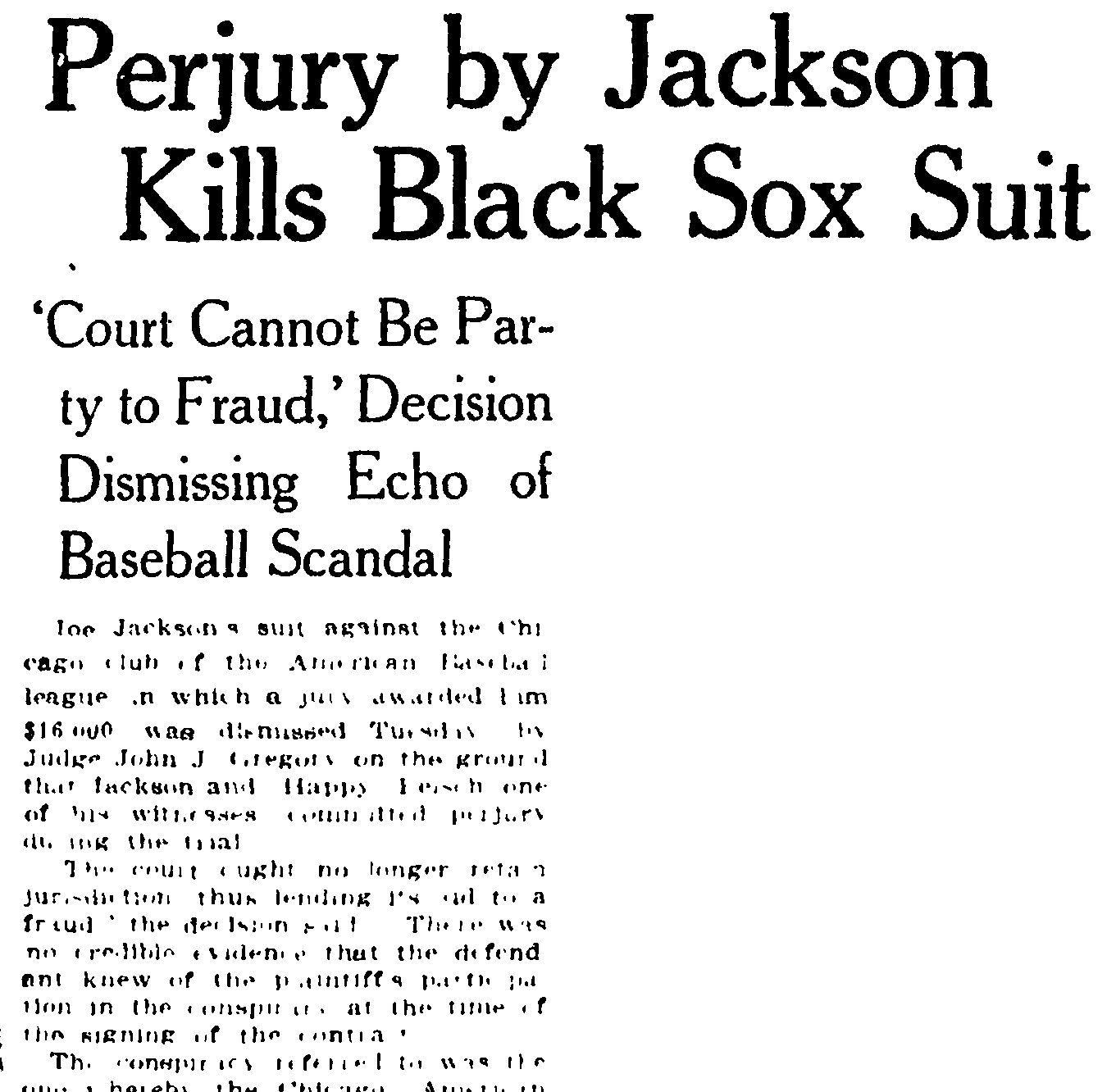

Throughout the Jackson cross-examination, Judge Gregory sat impassively. But inside, the normally genial jurist was seething. Several days later, Gregory made his displeasure with Jackson known. As soon as the jury had retired to deliberate its verdict, the plaintiff was unexpectedly summoned to the well of the court. There, Gregory informed Jackson that “you stand here self-convicted of the crime of perjury. You came to the wrong state, to the wrong city, to the wrong court.” Gregory then ordered bailiffs to take Jackson into custody, setting his bail at $5,000.68 Jackson was released shortly thereafter and back in court the following morning, but Judge Gregory was still rankled by the irreconcilability of the sworn testimony that Jackson had provided the grand jury and his testimony under oath at the civil trial, reiterating his view that Jackson “stands self-convicted and self-accused of perjury. Either his testimony here or his testimony before the Chicago grand jury was false. I think the false testimony was given here.”69

The jury’s verdict did little to improve Gregory’s mood. It returned a $16,711.04 judgment in Jackson’s favor. Astonished and indignant, Gregory lit into the jurors for ruling in favor of a “perjurer” and promptly vacated their verdict, specifying fraud and perjured testimony as the basis for the court’s action.70 When later explained to the press by foreman John E. Sanderson, however, the jury’s verdict had a defensible rationale. According to Sanderson, the panel had disregarded Jackson’s claims of innocence, but had awarded him his unpaid salary for the 1921 and 1922 seasons (plus the final days of the 1920 campaign) on the principle of condonation. As the jury viewed the proofs, the post-Series investigation of Comiskey’s detectives had left the Chisox boss aware of Jackson’s Series perfidy well before he tendered Jackson a new three-season contract in February 1920. By so doing, Comiskey had condoned (or forgiven) Jackson’s World Series misconduct. That being so, Comiskey could not avoid making good on that contract simply because the public had discovered what White Sox brass had known about Jackson all along.71

Although perjury during civil litigation rarely receives law enforcement attention, Milwaukee County District Attorney George A. Shaughnessy announced his office’s intention of investigating the Jackson testimony. “We will go over it carefully to see if there is anything that seems to warrant prosecution for perjury. If we find anything, we will make complaint, a warrant will be issued, and Jackson re-arrested,” he said.72, 73 By April, the district attorney was satisfied that Jackson, and Happy Felsch, as well, had testified falsely and obtained warrants for their arrest.74 On May 18, 1925, Jackson failed to appear for pretrial proceedings on a perjury complaint and a bench warrant was issued for his arrest by Judge George F. Page.75 But as long as Jackson stayed out of Wisconsin, there was little chance of his being apprehended. As far as can be discovered, proceedings on the perjury complaint outstanding against Jackson went no further.76

RENEWED CLAIMS OF INNOCENCE

Happily for Jackson, few outside Milwaukee paid heed to his civil lawsuit. By then, the world had moved on, with baseball, fueled by the unprecedented exploits of pitcher-turned-everyday-slugger Babe Ruth, embarked upon a golden age. To most fans, the Black Sox scandal and the likes of Shoeless Joe Jackson were ancient history.

Contrary to popular belief, the Black Sox did not remain silent after their banishment from the game.77 Jackson was among the most talkative, resolute in his claims of innocence but either erratic or inventive in his recall of scandal details. In 1941, Jackson told Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich that “I’m as innocent as you are. I had no part in that fix in 1919.”78 He then cited his World Series stats as proof of clean play. Jackson also complained about the “shoddy tricks” used by prosecutors against him, maintaining that the claim that he had confessed guilt was bogus. “There was no confession by me. That was trumped up by the court lawyers. They couldn’t produce it in court. They said it was stolen from the vaults. Does that sound right?”79 Povich was far too young to have covered the Black Sox trial in 1921, and reported Jackson’s assertions without reservation. Presumably, Povich was unfamiliar with the fact that only the original transcriptions of the Cicotte/Jackson/Williams grand jury testimony had been stolen. The theft was discovered well before trial, with the transcripts thereafter recreated by means of the grand jury stenographers’ handwritten notes. At trial, the Jackson grand jury confession was read at length to the jury.

Jackson reiterated his claims of innocence the following year to sportswriter Carter (Scoops) Latimer, an old friend.80 “I’m innocent of any wrongdoing,” Joe asserted, adding that “the Supreme Being is the only one to whom I’ve got to answer.”81 As before, Jackson cited his World Series statistics as proof of his innocence. He also debunked the notorious post-grand jury appearance “Say It Ain’t So, Joe” anecdote as a fabrication concocted by a “sob sister” sportswriter.82 Left unmentioned were the incriminating details about the fix that Jackson made to the press that same afternoon.83

The best-known of the Jackson apologias was published in the October 1949 issue of Sport magazine.84 Presented as a first-person Shoeless Joe narrative (as told to sportswriter Furman Bisher), the piece was treated as the last word on the Black Sox scandal — as Jackson would die only two years later — by Bisher and other Jackson sympathizers too young to have any personal memory of the affair. But Jackson’s reminiscences were marred by faulty recollection, confabulation of events, and the occasional outright falsehood. Indeed, the very first sentence of the piece — “When I walked out of Judge Dever’s courtroom in Chicago in 1921 … I had been acquitted by a twelve-man jury in a civil courtroom of all charges and I was an innocent man in the records”85 — was historically inaccurate. The jurist who presided over the trial was Judge Friend, not Dever, and Jackson and the others were found not guilty (different from innocent) by a criminal court jury, not a civil court one.86

The story then proceeds to the stunning allegation that Jackson was so troubled by World Series fix rumors swirling about that he went to club owner Comiskey’s hotel room in Cincinnati the night before Game One and pleaded to be removed from the line-up, lest his reputation be besmirched by playing in a rigged championship match.87 And this, Jackson said, was all witnessed by syndicated sports columnist Hugh Fullerton “who offered to testify for me at my trial later.” In fact, neither Fullerton nor any other witness was summoned to the stand by the Jackson defense.88 Three years later, however, Fullerton did testify as a White Sox defense witness in the Jackson civil suit. More important, Fullerton’s testimony contains no mention of Jackson trying to beg off playing in the 1919 Series. Nor does the alleged event appear anywhere in Fullerton’s writings on the scandal, inexplicable given that star player Jackson begging Comiskey to keep him out of the World Series would have been a sensational story that any sportswriter would have rushed into newsprint — had it ever happened.

The article takes another shot at the “Say It Ain’t So, Joe” anecdote, this time describing it as a fabrication invented by Chicago Daily News reporter Charley Owens. According to Jackson, the only person that he spoke to outside the courthouse after his grand jury appearance was a deputy sheriff whom Jackson gave a car lift home.89 But if this was true, where did the Chicago Daily Journal, Chicago Tribune and other news outlets get the specific fix details (Jackson’s complaint about being shortchanged on his bribe payout; his resentment of the brush-off given him by Gandil, Risberg, and McMullin; the thwarted Black Sox attempt to throw Game Three, etc.) attributed to Jackson? Like other followers of the fast-breaking scandal, the gathered pressmen were then unaware of such fix minutiae. Jackson’s revision of scandal events also made the far-fetched claim that prosecutors “kept delaying the trial until I personally went to the State Supreme Court judge, after which he ordered the case to be tried.”90 As the record documents, the issue was actually joined by a prosecution motion for a continuance of the proceedings presented to Circuit Court Judge William E. Dever who denied the application. Jackson, represented by able and experienced criminal defense lawyer Benedict Short, was no more than a silent bystander in the matter.91

Jackson even got small things wrong — his final White Sox contract, for example. It was a three-season deal, not five.92 He also got the story about the reputed origin of Comiskey’s feud with Ban Johnson backward. It was Johnson who had sent the smelly fish to Comiskey, not vice versa.93 There were others, as well. But misstatements large and errors small made no difference to Jackson admirers. And Shoeless Joe was still protesting his innocence when felled by the last of a series of heart attacks in December 1951.

FORENSIC ANALYSIS

Joe Jackson was a great ballplayer and, by all accounts, a nice man. But when it came to the Black Sox Scandal, Jackson inarguably perjured himself. The only issue, as observed by Judge Gregory in 1924, is whether Jackson lied under oath to the Cook County grand jury when he admitted entering the conspiracy to fix the outcome of the 1919 World Series, or whether it was Jackson’s duly sworn assertions of innocence in the matter thereafter that were false. The paragraphs below are devoted to forensic analysis of the question. Ultimately, the credible evidence — and reason, too — admits but one conclusion: Joe Jackson, while hardly an instigator or a proponent of the fix, was a knowing participant in the plot to rig the 1919 World Series; his protests of innocence, although prolonged, ring hollow.

Our analytical starting point is the grand jury testimony given under oath by Joe Jackson on the afternoon of September 28, 1920. As previously noted, Jackson’s account of the World Series fix was specific regarding events that he was involved in, full of peculiar detail, and highly incriminating, his claim of actually trying his best on the field notwithstanding.94 Jackson biographer Donald Gropman and other Jackson defenders confronting the issue usually try to explain away Shoeless Joe’s grand jury testimony by describing it as no more than regurgitation of information supplied to him by his interrogators.95 And regrettably, false confessions are a phenomenon that the criminal justice system has to deal with on a far-too-frequent basis. The Jackson grand jury testimony, however, betrays none of the indicia of a false confession. Here is why.

The essential component of the false confession is knowledge of the details of the underlying offense by those questioning a suspect — for if the questioner does not know what happened, how can he implant such information in the mind of someone else? When Joe Jackson was first confronted about his fix involvement in the Austrian law office, his inquisitors had only limited information about the matter. Club boss Comiskey, present but silent during the questioning, had presumably imparted the intelligence uncovered by his operatives to Austrian. But Comiskey’s minions had spent most of their time on the West Coast, trolling for dirt on Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin. They also spent time investigating reports on Buck Weaver and Happy Felsch. But no fix-related information had been uncovered on the other Black Sox.96 Rather, the only specific intel that Comiskey had about the fix that implicated Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams was the hearsay supplied to him by disgruntled St. Louis gamblers Harry Redmon and Joe Pesch. And that intel lacked detail. Sox attorney Austrian knew even less, while ASA Replogle’s grand jury probe had produced only scandal headlines. It had yet to uncover hard evidence against the targeted Sox players.97

Nor had Eddie Cicotte been over-enlightening. Summoned to the Austrian office ahead of Jackson, a distraught Cicotte readily admitted his own complicity in the plot to fix the Series outcome. And he specifically named Joe Jackson as one of “the men who were in on the deal.”98 But otherwise, Cicotte had not been particularly forthcoming. And he supplied Austrian, and later Replogle, with none of the fix-specific detail — about being propositioned privately by Chick Gandil; about the hold up of fix payoffs blamed on Abe Attell; about the $5,000 delivered to his hotel room by Lefty Williams prior to Game Five; about the denomination of the payoff currency, etc. — that Jackson would reveal to the grand jury later the same day. In short, Jackson’s detail-specific grand jury testimony could not have been implanted in his mind by Austrian or Replogle, since neither they nor Comiskey were aware of such details at the time.99 Only Jackson knew them.

For Jackson’s grand jury testimony about his fix involvement to be some sort of implanted fabrication, one must also conclude that every other Black Sox who named Jackson as a fix participant — Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, inferentially Happy Felsch, even Chick Gandil100 — maliciously accused an innocent man. No reason why his teammates would implicate Jackson falsely has ever been advanced because there is none. Nor is there any readily apparent reason for Judge McDonald to have testified falsely about Jackson’s admission of fix complicity in chambers prior to his grand jury appearance when McDonald appeared as a witness in the Jackson civil trial.

Finally, there are the Jackson quotations published in the Chicago Daily Journal, Chicago Tribune and elsewhere the day after Joe’s grand jury appearance. Once again, Jackson revealed fix details to the press unknown to Austrian, Replogle, and Comiskey. Indeed, some details — that attempts to dump Game Three had been frustrated by Dickey Kerr’s shutout pitching; that his confession was motivated by the brush-off about fix payment received from Gandil, Risberg, and McMullin — even went unmentioned during Jackson’s grand jury testimony. This next-day reportage, ignored by Jackson supporters and mostly neglected by scandal chroniclers, has never been discredited and further demolishes the notion that Jackson’s grand jury confession of fix guilt was contrived by some third party and then parroted to the panel by Joe as the scandal broke.

Interestingly, Jackson himself never asserted that the details of his grand jury testimony were fictions invented for him by others. Rather, Jackson insisted that he had never spoken the words memorialized on the grand jury transcript pages. This, of course, contradicted the concession of grand jury transcript accuracy made by the Black Sox defense during the criminal trial in Chicago. It was also belied by the testimony of grand jury stenographer Elbert Allen and panel foreman Henry Brigham, both of whom authenticated the transcript and its content during the Jackson civil trial in Milwaukee.101 In the end, Jackson’s dogged witness stand repudiation of his grand jury testimony was mind-boggling, so utterly preposterous that even plaintiff’s counsel Cannon effectively abandoned Jackson’s innocence claim in summation. Instead, Cannon focused his closing argument for judgment on the legal principle of condonation, maintaining that his client should be awarded his unpaid 1921–1922 contract salary because Comiskey had known that Jackson was a participant in the 1919 World Series fix, but had chosen to sign him to a new three-season contract despite that.

Balanced against the force of Jackson’s grand jury admissions of complicity in the fix is … pretty much nothing. Jackson and present-day supporters invariably cite his Fall Classic stats — the Series-leading batting average at .375, the club-high six RBIs — as proof of honest play. But statistics are always malleable, subject to partisan manipulation. More rigorous examination of how the 1919 World Series unfolded, for example, just as plausibly yields a damning assessment of Joe’s performance. During the first five games, the outer limit of the fix duration in most minds, clean-up batter Jackson notably under-produced, failing to drive in a single White Sox run. Most of Jackson’s gaudy stats were compiled only after the fix had been abandoned and the Black Sox had begun trying to win.

Jackson’s revised account of his World Series conduct, unveiled in the affidavit prepared by his criminal trial attorney and later embellished during his ensuing civil suit against the White Sox, also does the Jackson cause little good. Aside from its obviously self-serving nature, Jackson’s new story was plagued by implausible and/or inconsistent particulars. In same, for instance, Jackson was not so traumatized by rampant fix rumors that he had gone to club boss Comiskey’s hotel room prior to Game One and begged to be let out of the lineup (as he later told Furman Bisher). Rather, Jackson swore during his civil deposition testimony that he knew nothing of the fix until days after the Series was over, and was “dumbfounded” when Lefty Williams finally clued him in.

Of necessity, the revision of fix-related events also required movement of Williams’ delivery of the $5,000 payoff to Jackson from before the start of Game Five. It was now relocated to three days after the Series was completed. Not only did this contradict his own sworn grand jury testimony (and that of Williams, as well), it made no sense, as why would Jackson be hanging around a Chicago hotel room three days after the World Series was over? Clearly, there were no post-Series celebrations in town that he needed to attend. Far more likely was Jackson’s grand jury testimony that he and his wife had left Chicago for their home in Savannah the evening after the Series concluded. Jackson’s insistence that he had later tried to turn over the bribe money to Comiskey also rang false. At the civil trial in Milwaukee, it was established that the $5,000 was deposited in the Jackson account at the Chatham Bank & Trust Company in Savannah.102

That Joe Jackson was a likable fellow and persistent in his claims of innocence does not change the historical record. On the evidence, the call is not a close one, as a mere reading of this essay’s factual narrative should make plain. As he admitted under oath after first being confronted, Jackson was a knowing, if perhaps unenthusiastic, participant in the plot to fix of the 1919 World Series. And damningly, Jackson was just as persistent in his demands to be paid his promised fix payoff money as the Series progressed as he would later be in his disavowals of fix involvement. In the final analysis, Shoeless Joe Jackson, banished from playing the game that he loved while still in the prime of his career, is a sad figure. But hardly an innocent one.

WILLIAM F. LAMB is the editor of “The Inside Game,” the quarterly newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee, and the author of “Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation” (McFarland, 2013). Prior to his retirement, he spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey.

Notes

1 The White Sox led the league in team batting average with .287 and were secondin OPS and OPS+.

2 Comiskey later maintained that the evidence of player corruption uncovered by his investigators was inconclusive, and that the new contracts offered Jackson, Risberg, Williams, and Felsch had been predicated upon the legal advice of Alfred Austrian, counsel for the White Sox corporation. A far-more critical view of Comiskey’s conduct is provided in current Black Sox scholarship’s seminal work. See Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2006).

3 Decades later, it was revealed that Loomis’s call for a probe of the 1919 series had been ghostwritten by Chicago Tribune sportswriter James Crusinberry. See “A Newman’s Biggest Story,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956, 69-70. Crusinberry himself would later be a significant witness in early grand jury proceedings.

4 See e.g., the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and New York Times, September 20, 1920.

5 Philadelphia North American, September 27, 1920.

6As per notes of the Cicotte admissions taken down by Austrian and now preserved at the Chicago History Museum, Black Sox File, Box 1/Folder 2.

7 Unlike that of Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams, the grand jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte has not survived intact. But substantial portions of the Cicotte grand jury testimony were embedded in the transcript of his sworn January 14, 1924, deposition for the Jackson civil case and thereafter read into the civil trial record.

8 Chicago Evening Post, September 28, 1920.

9 Jackson repeated what he told McDonald in chambers, and more, when he subsequently testified before the grand jury. For space reasons, most particulars of the Jackson-McDonald conversation are omitted herein. But the complete testimony of Judge McDonald is preserved in the still-extant but difficult-to-access transcript of the Jackson v. Chicago White Sox civil case, pages 528-554.

10 McDonald civil trial testimony, page 552. See also Chicago Tribune, February 5, 1924. Decades later, Happy Felsch reportedly stated, “Playing rotten, it ain’t that hard to do once you get the hang of it. It ain’t that hard to hit a pop-up while you take what looks like a good cut at the ball.” Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1979), 117.

11 Jackson grand jury testimony [hereafter JGJ]5-21 to JGJ6-8. The long-lost transcript of the Jackson grand jury testimony first resurfaced in 1988, and is now viewable on various websites. See e.g., www.blackbetsy.com.

12 JGJ6-13 to 16.

13 JGJ6-17 to 24.

14 JGJ9-4 to 19.

15 JGJ4-19 to 23.

16 JGJ6-25 to JGJ7-9.

17 JGJ7-10 to 12.

18 JGJ4-20 to JGJ5-3.

19 JGJ12-5 to 12.

20 JGJ16-25 to JGJ17-12.

21 JGJ 17-23 to JGJ19-6.

22 JGJ16-9 to 14.

23 JGJ20-3 to 7.

24 JGJ11-11 to 24.

25 JGJ12-20 toJGJ13-24 and JGJ 14-3. Like Cicotte, Jackson was victimized by specious accounts of his testimony circulated by the Associated Press. Among other things, newspapers that subscribed to the AP wire printed that “Jackson said throughout the series he either struck out or hit easy balls when hits would have meant runs.” See e.g., Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1920. In fact, Jackson had said nothing of the sort.

26 JGJ15-13 to 14.

27 JGJ14-18 to 19; JGJ12-13 to 16.

28 JGJ22-11 to JGJ23-3; JGJ23-16 to JGJ24-5.

29 JGJ24-6 to 7.

30 Initially published in the Chicago Daily Journal and Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920, and then re-printed nationwide via the AP wire. See e.g., Cincinnati Post and New Orleans State, September 29, 1930, and Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1920. Unlike the more famous “Say it ain’t so, Joe” anecdote, the authenticity of these Jackson remarks has never been credibly challenged.

31 Chicago Daily Journal, Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920, and other newspapers nationwide.

32 Ibid.

33 During his grand jury appearance, Williams testified that eight White Sox players had agreed to the series fix, naming for the record “Cicotte, Gandil, Weaver, Felsch, Risberg, McMullin, Jackson, and myself.” See transcript of grand jury testimony of Claude Williams, September 29, 1920, page 30-20 to 24.

34 Chicago Evening American, September 30, 1920.

35 As reported in the Boston Globe, Chicago Evening Post, and New York Times, September 29, 1920.

36 The original indictments returned in People of Illinois v. Edward V. Cicotte, et al, can be reviewed via the website www.cookcountyclerkofcourt.com. Joe Jackson was among the Sox players charged, while indicted fix backers included professional athletes-turned-gamblers Abe Attell and Bill Burns, and banished star Hal Chase. Separate indictments were returned against a number of Chicago-area baseball pool operators. In March 1921, the original Black Sox indictments were administratively dismissed by SA Crowe, replaced by superseding indictments that re-charged all of the previously accused while expanding the roster of non-player defendants by five, including St. Louis gambler Carl Zork.

37 Los Angeles Times, November 13, 1920.

38 As reported in the Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times, November 24, 1920.

39 As quoted in the Boston Globe and Chicago Tribune, November 24, 1920. Although the venue would prove different from that envisioned by McDonald, his observation that Jackson risked exposing himself to a perjury charge proved prophetic.

40 A “bill of particulars” is a pretrial pleading that seeks more specific information about the charges from the prosecution.

41 Notorious Boston bookmaker Joseph “Sport” Sullivan and the shadowy Rachael Brown (probably Nat Evans, a capable lieutenant and business junior partner of reputed, but unindicted, fix financier Arnold Rothstein) were among the gamblers indicted in the Black Sox case.

42 An excerpt from the bill of particulars appears in Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 6, No. 2 (December 2013), 10.

43 Outside the jury’s presence, Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams testified in support of a defense motion to suppress their grand jury testimony. That testimony, however, was restricted to events attending their grand jury appearances, with no prosecution questioning about the actual fix of the World Series permitted by Judge Hugo Friend. At the hearing’s end, the motion was denied and redacted versions of the Cicotte/Jackson/Williams grand jury transcripts were later read to the jury at length. But to no avail, as the defendants were acquitted notwithstanding their grand jury admissions of guilt.

44 The only defendant who testified in his own defense at trial was gambler David Zelcer.

45 Partial transcripts of the motion proceedings survive in the Black Sox archive maintained at the Chicago History Museum (Box 1/Folder 4). The proceedings were also memorialized in reportage by the Chicago Herald Examiner, Chicago Tribune, and Savannah Daily News, July 26, 1921, and elsewhere. If defense claims were true, admission of the grand jury transcripts in evidence would have violated the constitutional due process rights of the accused.

46 Redaction means the removal of extraneous or inadmissible portions of the evidence. In the case of the Cicotte/Jackson/Williams grand jury transcripts this entailed the deletion of the names of the other defendants (Gandil, Felsch, Weaver, etc.) from the text, the anonym Mr. Blank being inserted wherever such a name appeared.

47 In the writer’s view, the prosecution presented a compelling case at trial against defendants Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams, and a strong one against codefendants Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and David Zelcer (if not versus the remaining accused). For one hypothesis about the verdict, see William Lamb, “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 44 (Fall 2015), 47-56.

48 The first of these lawsuits was instituted by Buck Weaver in October 1921, and sought unpaid salary for the 1921 season per the three-year contact that he had signed previously. Originally filed in Chicago Municipal Court, the Weaver suit was quickly transferred to the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois on diversity of citizenship grounds, the White Sox being incorporated in Wisconsin. In April 1922, Happy Felsch, Joe Jackson, and Swede Risberg filed state court suits against the White Sox in Milwaukee. Same posited various injury claims.

49 The press was barred from the Jackson deposition, and only ill-informed snippets appeared in newsprint until verbatim excerpts of the deposition were published by syndicated sports columnist Frank G. Menke. See e.g., the Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, April 23, 1923. Menke had previously authored a fawning portrait of Raymond J. Cannon, Jackson’s brash young civil attorney, and would prove a reliable Jackson apologist throughout the proceedings.

50 Per Menke in the Lincoln Star, April 23, 1923.

51 Menke, Lincoln Star.

52 Menke, Lincoln Star.

53 Menke, Lincoln Star.

54 For a detailed accounting of the civil litigation attached to the scandal, see William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013), 149-198.

55 According to Menke, “From Baseball to $100,000 a Year,” Atlanta Constitution, July 17, 1921, and elsewhere. Cannon, a decent ballplayer himself and once a semipro teammate of Jackson co-plaintiff Happy Felsch, was also actively engaged in trying to revive a major league players union.

56 See e.g., “Find Shoeless Joe Excellent Witness,” (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, January 31, 1924. Closer to home, local reportage was also initially favorable to the plaintiff. See the Milwaukee Sentinel, January 30, 1924: “Jackson made an excellent witness. He looked well on the stand. His answers came quickly and cleanly.”

57 One of the many fabrications that mar enjoyment of Eliot Asinof’s popular treatment of the Black Sox scandal is the assertion that the Jackson grand jury testimony had long been lost, and that Jackson was ambushed when the transcript “suddenly reappeared [from] Hudnall’s briefcase.” Eight Men Out (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1963), 289-290. The claim is absurd. The transcript of Jackson’s grand jury testimony (and that of Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams, too) had been used extensively during the earlier Black Sox criminal trial and was tantamount to a matter of public record. Nor was the Jackson side surprised by Hudnall’s possession of it, plaintiff’s attorney Cannon having made a motion to preclude the transcript’s use at the civil trial. That motion was denied by Judge Gregory.

58 Jackson v. Chicago White Sox civil trial transcript [hereinafter JTT], page 151.

59 JTT, page 156.

60 JTT, pages 159-160.

61 JTT, page 162.

62 JTT, page 220.

63 JTT, pages 197-198

64 JTT, page 200.

65 JTT, page 188.

66 JTT, pages 154-155.

67 JTT, page 160.

68 As reported in the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel, February 15, 1924. The day before, Judge Gregory had found plaintiff’s rebuttal witness Happy Felsch in contempt for repudiating what was incontestably his signature on his 1920 White Sox contract. Felsch was thereupon taken into custody, but released later that evening when two local attorneys posted his $2,000 bail.

69 JTT, pages 1686-1687. See also, the Milwaukee Evening Sentinel, February 15, 1924. The perjury-related crime of false swearing can be deemed a sort of self-accusing, self-convicting offense. In one of its forms, false swearing does not require the demonstration that a particular statement given under oath was false. Conviction can rest upon proof that the accused uttered inconsistent statements on the same subject matter while testifying under oath at two different judicial proceedings. It does not matter which of the two inconsistent statements is false, just that one of them has to be (e.g., giving two different birth dates).

70 JTT, pages 1694-1696. See also, the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Evening Sentinel, February 15, 1924.

71 As reported in the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Evening Sentinel, February 15, 1924.

72 Over more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor, the writer recalls only three perjury prosecutions, each of which involved false witness testimony during a very serious criminal case. Prosecutors generally take little interest in alleged perjury during civil litigation, leaving the affected parties and/or the court to pursue their own remedies.

73 As per the Milwaukee Journal, February 16, 1924, and Chicago Tribune, February 17, 1924. The perjury arrest of Jackson ordered by Judge Gregory was a contempt of court-type sanction. Criminal proceedings against Jackson could only be instituted by a law enforcement agency, like the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office.

74 As reported in the Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1924.

75 As reported in the Milwaukee Sentinel and Sheboygan (Wisconsin) Press, May 18, 1925. That same date, Felsch appeared before Judge Gregory and pled guilty to a reduced charge of false swearing. He was sentenced to a one-year term of probation.

76 Decades later, it was reported that the charge had been dismissed. See the Milwaukee Journal, March 13, 1986. In 2010, letters to the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office from the writer about the disposition of the Jackson perjury complaint went unanswered.

77 A complete accounting of statements uttered by the Black Sox is provided in Jacob Pomrenke, “After the Fall: The Post-Black Sox Scandal Interviews,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 8, No. 1 (June 2016), 6-9.

78 Shirley Povich, “Say It Ain’t So, Joe,” Washington Post, April 11, 1941.

79 Povich, Washington Post.

80 Back in 1908, Latimer, then a cub reporter for the Greenville (South Carolina) News, had hung the Shoeless Joe moniker on Jackson after Joe had discarded tight-fitting new spikes for a few innings during a minor league game.

81 Carter (Scoops) Latimer, “Joe Jackson, Contented Carolinian at 54, Forgets Bitter Dose in His Cup and Glories in His 12 Hits in ’19 Series,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1942.

82 Latimer, The Sporting News.

83 See again, the Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Post, and New Orleans State, September 29, 1920.

84 See “This Is the Truth,” by Shoeless Joe Jackson as told to Furman Bisher, Sport, October 1949.

85 “This Is the Truth,” 13.

86 Months prior to the trial, Judge William E. Dever had rendered a significant pretrial ruling in Black Sox defense favor, denying a prosecution motion for an indefinite continuance of the proceedings. The short peremptory trial date then set by Dever prompted State’s Attorney Crowe to administratively dismiss the original indictments returned in the case, and re-present the matter to the grand jury for superseding charges.

87 This sensitivity and desperate reaction to pre-series fix rumors was a stunning departure from events recounted in Jackson’s sworn April 1923 civil case deposition. Then, Jackson had claimed to be oblivious to the series corruption until Lefty Williams informed him about it several nights after the series was over.

88 “This Is the Truth,” 14. A number of witnesses were presented at the criminal trial by the Gandil defense. None of the accused players testified before the jury at trial, but Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, and Lefty Williams did take the stand out of the jury’s presence in support of the unsuccessful defense motion to suppress their grand jury testimony.

89 “This Is the Truth,” 14.

90 “This Is the Truth,” 83.

91 Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 89-90.

92 “This Is the Truth,” 83.

93 “This Is the Truth,” 83.

94 Under then-applicable Illinois criminal law, the offense of conspiracy was committed the moment that two or more persons agreed to commit an unlawful act. No action (overt act) needed be taken by the conspirators in furtherance of their plan for the crime to have been committed. See People v. Lloyd, 304 Ill. 23, 136, N.E. 505 (Ill. Supreme Ct. 1922). Given that, the purported abandonment of the plot to throw the World Series by Jackson (or any of the other Black Sox defendant) had no legal effect. Nor did the criminal law principle of renunciation apply once a bet on the Series outcome had been placed by an in-the-know gambler with some unsuspecting White Sox backer. At that moment, the crime of conspiracy was irrevocably committed.

95 Donald Gropman, Say It Ain’t So, Joe! The True Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson (New York: Citadel Press, 3rd ed., 2001), 185-190.

96 Gene Carney, “Comiskey’s Detectives,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Fall 2009), 108-116.

97 For a session-by-session account of developments during the first Cook County grand jury investigation of the fix, see again, Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 29-79.

98 As per notes of the Cicotte interview taken by Austrian now reposed in the Chicago History Museum’s Black Sox archive (Box 1/Folder 2).

99 For further demolition of the argument that Jackson’s grand jury testimony was false and implanted in his mind by others, see Craig R. Wright, “The Austrian Conspiracy,” www.BaseballsPast.com, 2015.

100 “This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series,” by Arnold (Chick) Gandil, as told to Mel Durslag, Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

101 JTT, page 599, et seq. (Allen); JTT, Page 648, et seq. (Brigham). During his testimony, Allen recited the 128 or so answers that Jackson had denied giving to the grand jury during his testimony earlier in the civil trial.

102 JTT, page 1169 et seq. (deposition of bank teller John J. Cornell admitted in evidence).