No ‘Solid Front of Silence’: The Forgotten Black Sox Scandal Interviews

This article was written by Jacob Pomrenke

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

When legendary sportswriter Furman Bisher died in 2012, his obituary in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution repeated a claim that had been casually tossed around for many years — including by Bisher himself:

One of the biggest “scoops” of his career occurred in 1949, when “Shoeless” Joe Jackson gave Bisher and Sport Magazine his only interview since 1919, the year Jackson was ousted from baseball in the “Black Sox” scandal.1 [Emphasis added.]

The interview between Bisher and Jackson, conducted at the latter’s home in Greenville, South Carolina, appeared in Sport’s October 1949 edition with the headline “This is the Truth!” Jackson’s first-person account of the 1919 World Series fix and his subsequent banishment from baseball is, in the words of author Gene Carney, “one of the documents that nobody curious about Jackson can pass up.”2 Thankfully, BlackBetsy.com now makes a copy of the article available online.3 But even the Internet’s most comprehensive Joe Jackson website has erroneously claimed that it is “the only interview Joe Jackson ever gave concerning the infamous World Series.”4

That couldn’t be further from the truth. In the three decades between Jackson’s final major-league game in 1920 and his death in 1951, nearly a dozen interviews with Shoeless Joe appeared in such widely read publications as The Sporting News, Washington Post, and syndicated wire-service articles that ran in newspapers all over the country. Closer to home, Jackson maintained a friendly rapport with veteran South Carolina sports writers Jim Anderson and Carter “Scoop” Latimer, who kept readers updated on Jackson in numerous columns for the Greenville News during the 1930s and 1940s.5

- Related link: Click here for a list of all known interviews with 1919 World Series participants

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Jackson wasn’t the only Black Sox player to talk to the press in the years following the scandal. In the fall of 1956, Chick Gandil sat down with Los Angeles-based sportswriter Melvin Durslag for a tell-all exposé about the 1919 World Series fix that appeared in Sports Illustrated.6 Gandil’s rambling, self-serving interview made national headlines and shined a new spotlight on the old scandal. After the SI article was published, the Chicago Tribune called Eddie Cicotte and Happy Felsch for their reactions. Hearing of Gandil’s assertions, Felsch said, “They’re all wrong.” Cicotte added, “I took my medicine and I’ve forgotten about it.”7

Cicotte and Felsch had more to say about the scandal — and so did many other players involved in the 1919 World Series.

“A Solid Front of Silence”

It’s easy to believe the Black Sox had no interest in “talking about the past,” as another embattled ballplayer (Mark McGwire) famously told Congress during an investigation into baseball’s recent performance-enhancing drug scandal. Ever since the Black Sox were banned in 1921, finger-wagging sportswriters have perpetuated the idea that the Chicago players disappeared from the public eye and lived out the rest of their lives with their heads hung in shame.8

When Eight Men Out author Eliot Asinof went looking for the surviving Black Sox in the early 1960s, he encountered resistance from almost every ballplayer he found. Happy Felsch was a notable exception, and the old ballplayer finally loosened his lips after Asinof showed up at his door with a bottle of Scotch.9 Felsch became one of Asinof’s primary sources for the book — the author was so appreciative that he dedicated another book, Bleeding Between the Lines, to the former star outfielder. But Asinof’s attempts to interview Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Eddie Cicotte didn’t go so well. Even the “Clean Sox” like Red Faber, Ray Schalk, and Dickey Kerr didn’t have much to say to Asinof.

Asinof attributed their reluctance to talk to the stigma that everyone involved — even the innocent players — supposedly felt about the 1919 World Series. As he wrote in Eight Men Out:

“Though [the Black Sox] had almost no contact with each other over the decades that followed, they maintained a solid front of silence to the world. It was as if a pact existed between them and the forces that had brought them to it. It was a silence of shame and sorrow and futility. It was also a silence of fear, for the threats hanging over them made talking a doubly difficult adventure. But mostly, it was a story rooted in the bitterness and frustration of their lives. There seemed to be no way to talk of it that made sense to them, no way that would give some measure of understanding and, perhaps, vindication to their actions.”10

Asinof’s own experiences talking to the ballplayers seemed to back up that claim: The scandal was a subject best left alone. Hall of Fame pitcher Red Faber expressed a similar sentiment when Asinof met with him in Chicago in the early 1960s:

“It’s tough to talk about it. I see some of the boys — like Schalk, for instance — and though he was as straight as an arrow, he won’t even mention the Series. They were scared, I guess. Scared of the gamblers.”11

If a prepared and skilled interviewer like Asinof could not get these players to talk, after doing more homework on the scandal than anyone before him, what chance did any other writer have? Based on his own dealings with the players, Asinof may have gotten the impression that the “solid front of silence” was more widespread than it was. Decades later, Asinof repeated the idea that had become ingrained as part of the mythology of the scandal: “There’s a lingering impact on all of baseball. You don’t talk about this thing,” he told Sports Collectors Digest in 1988. “Even sympathetic ballplayers who did not involve themselves in the fix refused to talk.”12

As Asinof was writing Eight Men Out, he was well aware of Joe Jackson’s Sport interview and Chick Gandil’s Sports Illustrated account. He also knew that Westbrook Pegler, the Pulitzer Prize-winning political columnist, followed up on the SI article in 1956 by visiting Cicotte in Detroit, and Felsch in Milwaukee, and talking on the phone with Risberg.13,14,15 In Pegler’s five-part series on the Black Sox Scandal, which was distributed to hundreds of newspapers by the King Features Syndicate, Cicotte and Felsch expressed some regret for their roles while Risberg remained publicly defiant, as he would for the rest of his life.

These were by far the most prominent Black Sox interviews discovered by Asinof in the course of his research.16 But in an era long before text-searchable online archives, many other interviews were lost to obscurity, including those buried in small local newspapers near-impossible to discover prior to digitization. Other writers had been successful in getting not only the White Sox, but also the victorious Cincinnati Reds to talk about the tainted 1919 World Series.

More than 20 White Sox and Reds players spoke on the record about the scandal afterward, in at least 85 separate interviews. The players weren’t all forthcoming and their memories weren’t always accurate. Their words were sometimes embellished by reporters and, invariably, the players contradicted themselves or each other. There are no “smoking guns,” no special insights that help to clear up any of the longstanding mysteries surrounding the scandal. More often, there are claims of innocence or ignorance that don’t ring true given what is known now about the 1919 World Series. But like many common myths about the scandal, the idea that the Big Fix was too shameful or too dangerous for anyone to talk about doesn’t seem to hold up to scrutiny.

Black Sox Interviews

The Black Sox players were not that difficult to find in their years of exile. While it was sometimes reported they had “dropped out of sight” or “quietly vanished,” some writers did their due diligence to look them up.17,18

After he was banned by baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1921, Joe Jackson settled first in Savannah, Georgia, then moved back home to South Carolina. He played some semipro ball and was a successful businessman in both states, operating a liquor store, a barbeque restaurant, and a dry-cleaners, where he was occasionally visited by curious reporters. In 1927, Harry Grayson of the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) wire service spoke with Jackson about his punishment: “I don’t like being called an outlawed player because I fail to see where I am one,” Jackson said. “I was never convicted of any charge in any court.”19 It was a refrain he repeated to anyone who asked.

He also told Grayson he didn’t “care a whoop” about having his name cleared, but a few years later, a reinstatement effort was led on his behalf by Greenville mayor John Mauldin in 1933. By then, Jackson’s stance had softened. “About all I want now is a minor-league connection,” he told the Associated Press. “That’ll make me happy.”20

Judge Landis, predictably, ignored the appeal and Jackson soon stopped asking. But he never failed to take a shot at the baseball commissioner whenever the subject came up. “Sure, I’d love to be in the game,” he told the NEA’s Richard McCann in 1937. “But I’d rather be out than to be in and bossed by a czar.”21 In 1941, Shirley Povich of the Washington Post spent an afternoon with Jackson when the Washington Nationals played a spring training exhibition game in Greenville. Jackson said he was “not bitter toward baseball … [but] I don’t care for Judge Landis.”22

Other than proclaiming his innocence, Jackson rarely offered details in interviews about the 1919 World Series, preferring to let his .375 batting average and Series-high 12 hits stand as his primary defense. One notable exception was in 1932 when he opened up to the NEA’s William Braucher about a key detail that he had never revealed publicly: “[I] asked to be suspended before the World Series,” Jackson said. “I didn’t want to play hard after I heard what was going on. But I had to play and I did play.”23

Near the end of his life, Jackson repeated this story in 1949 to Furman Bisher and in 1951 to John Carmichael, both writing for Sport magazine.24 But his claim went virtually unnoticed at the time, despite the serious implication that Jackson had tried to inform White Sox officials of the fix before the Series began and they had ignored him. In his groundbreaking book Burying the Black Sox, author Gene Carney devoted most of a chapter to Jackson’s request, suggesting that this incident, if verified, would have been the start of a cover-up engineered by White Sox owner Charles Comiskey to sweep the scandal under the rug.25

But did it ever happen? The reliability of Jackson’s claim is still heavily disputed. He had two chances to tell this story under oath — during his grand jury testimony in 1920 and his civil-trial deposition in 1923 — but never said a word about asking to be taken out of the lineup. He also didn’t mention it in a long feature profile that appeared in The Sporting News in 1942, written by his old friend Scoop Latimer of Greenville.26 The Furman Bisher interview from 1949 contains a number of details that are inaccurate, such as Jackson misremembering how many outfield assists he had during the World Series, or other anecdotes that cannot be corroborated. In the end, only these vague quotations from Jackson’s interviews remain — a tantalizing piece to the puzzle that may never be connected for sure.

Buck Weaver was even more vocal about the 1919 World Series than Jackson. He continued to play semipro and outlaw baseball for more than a decade after his banishment in 1921, and then made his home in Chicago, where he regularly could be found at old-timers’ banquets with baseball friends like former teammates Red Faber and Ray Schalk. Weaver was outspoken about the injustice of his lifetime ban and often lobbied to have his name cleared.

In January 1922 — five months after he was banned — Weaver made his first public plea for reinstatement, telling reporters that he had recently met with Judge Landis to make his case in person. He acknowledged that he was aware of the fix rumors during the World Series: “The only doubt in my mind was whether I should keep quiet about it or tell Mr. Comiskey. I was not certain just what men, if any, had accepted propositions, or whether they accepted. I couldn’t bring myself to tell on them, even had I known for certain. I decided to keep quiet and play my best.”27 After the season, Landis denied Weaver’s request on the grounds that he had never adequately explained why he had attended the pre-Series fix meetings with the other players. Landis ominously declared, “Birds of a feather flock together.”28

Weaver continued to appeal to the judge over the years and used every opportunity to plead for reinstatement. After Landis’ death in 1944, Weaver stepped up his efforts, thinking a new commissioner might be more sympathetic to his cause. He appeared on WGN Radio and was interviewed by broadcaster Jack Brickhouse in 1947.29 He also wrote a letter to commissioner Ford Frick in 1953. In the fall of 1954, Weaver was visited by author James T. Farrell at the Morrison Hotel in Chicago. Buck was still unclear about what he had done to deserve such a harsh punishment: “A murderer even serves his sentence and is let out. I got life. … Landis wanted me to tell him something that I didn’t know. I can’t accuse you and it comes back on you and I am… a goof. That makes no sense. I had no evidence.”30

Chick Gandil gave an explosive interview that appeared in Sports Illustrated on September 17, 1956.

Weaver’s death in 1956, followed shortly thereafter by Chick Gandil’s sensational exposé in Sports Illustrated, launched another round of attention on the Black Sox Scandal. The syndicated political columnist Westbrook Pegler, who had covered the 1919 World Series early in his career, went to the homes of Eddie Cicotte, Happy Felsch, and Swede Risberg that summer to ask them more about the tainted Series. Cicotte and Felsch looked back with regrets. “We done wrong and we deserved to get punished,” the 72-year-old Cicotte said from Detroit. “But not a life sentence. That was too rough. I could have earned a living coaching later but they wouldn’t let me.”31 Felsch, then 65, said he had to give up his tavern in Milwaukee because he “had so much trouble with argumentative drinkers about the 1919 Series.”32 Risberg, at age 61, continued to insist he had done nothing wrong to earn his punishment; instead, he steered the conversation with Pegler more toward his observations on the modern game and about his son Gerald, who was then playing ball at Chico State College in California.33

No interviews have turned up yet for the remaining two Black Sox players, pitcher Lefty Williams and infielder Fred McMullin, who both lived quiet lives in California for decades after the scandal. After Gandil’s Sports Illustrated article appeared in 1956, Williams’ wife Lyria wrote a letter to her good friend Katie Jackson, Shoeless Joe’s widow, in which she expressed displeasure at the old scandal being brought up: “You sure have trouble with the newspaper men in the South. … I am glad they do not know where we are. We would send them chasing if they came here.”34 McMullin may not have talked to any reporters, but according to family lore, he once wrote up his version of the scandal in a file that was to be revealed after all the Black Sox players had died — and his wife Delia destroyed the letter.35 McMullin might have played a much larger role in the scandal than is commonly believed, but without his own words, that may never be known for sure.36

The last surviving Black Sox, Swede Risberg, remained defiant over the years and he occasionally took to the press to proclaim his innocence. In 1931, while playing semipro ball in South Dakota, he complained to a reporter for the Sioux Falls Argus-Leader about how much money he had lost because of the lifetime ban, which he estimated to be about $150,000 or $200,000. “That’s a terrible penalty for a man who believes himself the victim of circumstantial evidence. … [Risberg] still swears he was innocent of any conniving with gamblers or that he was promised or received any of the money which was accepted by other members of the team.”37

A few years later, as the Great Depression wiped out his savings and times were tough for an outlaw ballplayer, Risberg moved back home to San Francisco and made a public plea to be reinstated. “If I had held up a bank, I would have paid the penalty by this time and would be out of jail and able to earn a living,” he said in 1934.38 There is no record that Judge Landis ever responded to the Swede, who went on to rebound from his struggles and open a successful nightclub near the California-Oregon border by the time Pegler visited him two decades later.

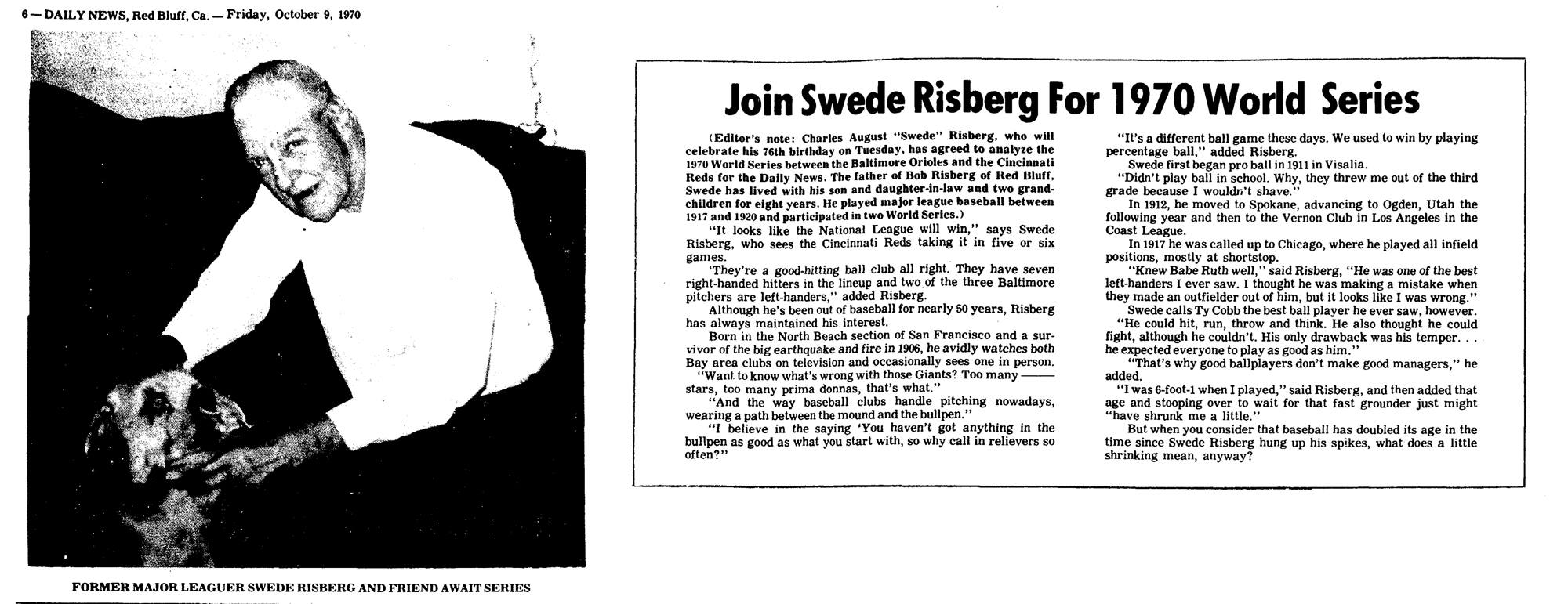

Risberg spent his final years living with his son Robert in Red Bluff, California. In 1970 he was asked to preview the upcoming World Series as a guest columnist for the local newspaper. Swede’s columns were short and amiable, and no mention was made of his sordid past. But anyone who knew his history might have raised an eyebrow at the irony of his prediction: he picked the Cincinnati Reds to win.39

Swede Risberg picked the Cincinnati Reds to win the 1970 World Series in the Red Bluff (California) Daily News.

Chick Gandil opened up one more time after the SI article, in a two-part interview with Dwight Chapin of the Los Angeles Times in 1969, for the 50th anniversary of the tainted World Series. He was 82 years old and in poor health, but instantly regained his old fire at the mention of baseball’s first commissioner. “We were exonerated,” he said. “But that damned Judge Landis took more power than the courts and we were blacklisted for all time. … I just get tired of being made the goat in all this. I have taken an awful beating in this thing.”40 As he had done in 1956, Gandil again insisted that the World Series was never thrown, citing his own crucial RBI singles in Games Three and Six, and that he hadn’t received any money from gamblers. As Chapin wrapped up the interview, Gandil looked squarely at him and said, “I’m going to my grave with a clear conscience, you understand?”41

Eddie Cicotte offered a more penitent tone in his final interview, when Joe Falls of the Detroit Free Press came to visit his 5½-acre strawberry farm in 1965. “I admit I did wrong,” Cicotte said, “but I’ve paid for it the last 45 years. … I don’t know of anyone who ever went through life without making a mistake. I’ve tried to make up for it by living as clean a life as I could.”42 He offered no excuses for his involvement in the Black Sox Scandal and seemed genuinely at peace with his life. When Falls shook hands with the old pitcher and waved goodbye, he sized up Eddie’s plaid shirt, blue denim pants, and tan shoes. “But what I noticed for the first time were his socks,” Falls wrote. “They were white.”43

Clean Sox Interviews

When Hall of Fame catcher Ray Schalk learned of Eddie Cicotte’s death in 1969, he felt a pang of affection for his old, disgraced batterymate. “He made my work easy behind the plate,” Schalk told the Chicago Tribune. He also said the pitcher had “a great sense of humor and was a great storyteller.”44 But a few months later, when the Associated Press contacted him for a story on the 50th anniversary of the tainted series, Schalk clammed up. “You can ask me anything in the world except [that],” he said. “I have my personal feelings about it all. It’s one of the saddest things that ever happened.”45

Over the years, Schalk wavered back and forth on his willingness to talk publicly about the 1919 World Series. At times, he was candid and offered unique insight about the Series that only a participant could provide. On other occasions, he claimed to know nothing about the fix and “had no reason to suspect anything.”46 Eliot Asinof’s attempt to interview him at Purdue University, where Schalk was an assistant baseball coach, ended before it even started. Schalk threw the writer out of his office.47 Asinof later wrote of Schalk’s silence, “He could not bear the shame of the fix, for this was his team, these were the men he lived with, this was the game he played and loved.”48

But Schalk had been more open in the past. In fact, he had been the very first of the “Clean Sox” to open his mouth about the World Series fix rumors back in 1919 — and it got him in big trouble. Two months after the Series ended, Schalk spoke to an investigative reporter, Frank O. Klein, for a small Chicago-based gambling trade publication called Collyer’s Eye. He said seven of his teammates wouldn’t return to the White Sox roster in 1920 … and he even named them: Cicotte, Felsch, Gandil, Jackson, McMullin, Risberg, and Williams.49 (Everyone but Buck Weaver, whose name wasn’t being tossed around in the fix rumors then.) When The Sporting News picked up the story, Schalk was chastised by White Sox owner Charles Comiskey and he immediately retracted his comments.50

Schalk must have learned his lesson from this incident, because it took him more than twenty years before he spoke openly about the scandal again. In a 1940 profile for The Sporting News by veteran Chicago writer Ed Burns, Schalk said he had turned down “considerable sums” to tell the “inside story” of the 1919 Series and still had “confused emotions” about it all.51 He also denied reports that the Black Sox were disgruntled: “Whatever happened was not traceable to any general discontent.”

Eddie Collins was also quick to go on the record soon after the scandal was exposed. In an interview with Collyer’s Eye on October 30, 1920, he said “there wasn’t a single doubt in my mind” as early as the first inning of Game One that the games were being thrown. He added, “If the gamblers didn’t have Weaver and Cicotte in their pocket, then I don’t know a thing about baseball.”52

Collins’ accusation against Weaver was not the last time he pointed a finger in Buck’s direction. In 1943, the Hall of Fame infielder told Joe Williams of the New York World-Telegram that he “should have recognized the tip-off in the very first game” when Weaver missed a hit-and-run sign and Collins “was out by a yard at second.” Collins asked Buck if he “was asleep,” and Weaver snapped, “Quit trying to alibi and play ball.”53

Weaver’s reply could be damning evidence that he was more involved with the fix than is commonly believed, but it also could be just a reflection of his cool relationship with Collins, who wasn’t well liked in the White Sox’s dissension-riddled clubhouse. But Collins’ tone changed over the years and he began to back off from his comments that he had known much about the scandal. “I was to be a witness to the greatest tragedy in baseball’s history — and I didn’t know it at the time,” he told The Sporting News in 1950. “I didn’t for an instant believe at that time they would engage in anything as dastardly as a conspiracy to throw a ball game or a Series and let the rest of their teammates down.”54

Dickey Kerr, a rookie pitcher in 1919 who won two games in the World Series, also spoke publicly about his suspicions. In a 1937 interview with David Bloom of the Memphis Commercial-Appeal, Kerr said, “We knew it all the time. A newspaperman tipped me off. But what could we do?”55 Reserve catcher Joe Jenkins told the Fresno Bee in 1962 that the fix rumors were openly discussed inside the clubhouse. He said he noticed Chick Gandil “betting heavily” on the World Series games, but “I didn’t think much of it as we used to get good odds and bet all the time.”56

Outfielder Eddie Murphy expressed similar sentiments in a 1959 interview with Chic Feldman of The Scrantonian in Pennsylvania. He said manager Kid Gleason held a team meeting early in the Series, declaring, “I hear $100,000 is to change hands if we lose.” But his threats to expose the fix weren’t enough to get his team back on track. Murphy also talked about rumors that the Black Sox had thrown games in 1920, too: “We knew something was wrong for a long time, but we felt we had to keep silent because we were fighting for a pennant. We went along and gritted our teeth and played ball. It was tough.”57

By and large, the “clean Sox” were no longer angry at their teammates for selling out. But they remained disappointed at what might have been: a White Sox baseball dynasty that could have challenged Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees for American League supremacy for years to come.

Hall of Fame pitcher Red Faber said, “Loss of those men ruined our club. If we had kept them, we would have gone on winning pennants, or fighting for them, for years.”58 Added Eddie Collins, “They were the best. There never was a ballclub like that one, in more ways than one.”59

Cincinnati Reds Interviews

To a man, the Reds players had one thing to say whenever they were asked about the tainted World Series: They all insisted they didn’t need any help to beat the powerhouse White Sox. “Sure, the 1919 White Sox were good. But the 1919 Cincinnati Reds were better,” Hall of Fame outfielder Edd Roush told Lawrence Ritter, author of The Glory of Their Times. “I’ll believe that till my dying day. … We could have beat them no matter what the circumstances!”60

Roush liked to point out that the Reds had a deeper pitching staff and a more well-rounded lineup, which matched up well against the White Sox in a best-of-nine series.61 “I still don’t see why the White Sox were supposed to be such favorites to beat us,” Reds third baseman Heinie Groh told Ritter. “I didn’t see anything that looked suspicious. I think we’d have beaten them either way; that’s what I thought then and I still think so today.”62

There is reason to believe the Reds were indeed the better team, and there is also some evidence that the conspiring Chicago players called off the fix early in the Series after failing to receive payment from the gamblers. At any rate, the Reds players said they didn’t seem to notice anything suspicious — at least on the field. Outfielder Greasy Neale, who went on to become a Hall of Fame football coach in the NFL, told writer Grantland Rice in 1945, “The fellows rumored as the crooks starred all thru the series. … I’ll admit, they had to be the greatest artists in baseball history to throw any game outside the first one, for those labeled as crooks looked and acted like great ballplayers. … How could we figure they were crooked?”63

Years later, pitchers Dutch Ruether and Slim Sallee said they had a hard time believing the fix was in. “No one ever dreamed there would be anything shady in a World’s Series,” Sallee told The Sporting News.64 Said Ruether: “In that first game, I got two triples, a single, and a base on balls — a record that’s never been beaten. And then I found out they were only foolin’.”65

By the end of the Series, the Reds could no longer claim to be surprised about rumors of a fix — because one of their own teammates was being offered a bribe to lose, at least according to Edd Roush. Before the decisive Game Eight, Roush said, manager Pat Moran confronted pitcher Hod Eller in the clubhouse. Eller confirmed that he had been approached by gamblers and offered $5,000, but he said he had run them off. Moran cautiously allowed Eller to pitch and the right-hander responded with a stellar performance as the Reds won the game and clinched the Series. Roush first told this story to a New York reporter in 1937 and then repeated it in print many times until his death more than a half-century later.66 His former teammate, Ray Fisher, corroborated the story in an interview with the Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch years later.67 Like many of the interviews mentioned above, Roush’s story raises as many questions as it answers, adding a new layer of complexity to our ever-evolving collective knowledge of the Black Sox Scandal.

For decades, the “solid front of silence” was a key part of that story. In his classic history of the American League, published in 1962, historian Lee Allen noted that the “honest players on the team who still survive will not talk,” a phenomenon he found “passing strange.”68 Dr. Harold and Dorothy Seymour also claimed “the players, honest as well as accused, have maintained an almost unbroken silence.”69 Few writers or fans have seriously challenged that notion in the years since. But it’s clear the players involved in the 1919 World Series were often willing to talk about what happened. Thanks to the power of the Internet, their words are much easier to find today using searchable newspaper archives than they were when Eliot Asinof was writing Eight Men Out.

More interviews with White Sox and Reds players almost certainly are waiting to be discovered in the future. Many daily newspapers from Chicago and Cincinnati, let alone all the other places these players lived and worked, haven’t been digitized yet. But one thing can now be said for sure: When asked about the scandal, the participants often answered.

“I don’t know whether the whole truth of what went on there with the White Sox will ever come out,” Edd Roush told author Lawrence Ritter in 1964. “Even today, nobody really knows exactly what took place. Whatever it was, though, it was a dirty, rotten shame.”70

JACOB POMRENKE is SABR’s Director of Editorial Content, chair of the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, and editor of “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (2015). He lives in Scottsdale, Arizona, with his wife, Tracy Greer, and their cats, Nixey Callahan and Bones Ely.

Photo credits

Joe Jackson and Furman Bisher, 1949: Courtesy of Mike Nola/BlackBetsy.com

Chick Gandil, Sports Illustrated, 1956: Author’s collection

Swede Risberg, Red Bluff Daily News, 1970: Author’s collection

Notes

1 Alexis Stevens, “Sportswriter Furman Bisher dies at 93,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 19, 2012. Accessed online at http://www.ajc.com/news/sports/sportswriter-furman-bisher-dies-at-93-1/nQSJx/ on November 3, 2015. The author has added emphasis.

2 Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006), 63-64.

3 http://www.blackbetsy.com/theTruth.html

4 Ibid.

5 Latimer is best known as the sportswriter who gave Shoeless Joe his iconic nickname during a minor-league game in 1908.

6 Arnold (Chick) Gandil, as told to Melvin Durslag, “This is My Story of the Black Sox Series,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

7 “’Black Sox’ Blast Gandil ‘Confession’,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1956.

8 For one early example, see: Frank G. Menke, “Crooked Players Find Themselves Despised By All,” King Features Syndicate, Idaho Statesman, April 4, 1922. No meaningful effort is made to accurately report on the Black Sox players’ whereabouts. Lefty Williams is described as “loafing day after day,” Swede Risberg as “idle and seemingly broke.” Joe Jackson has “the years stretching before him, barren of baseball hope.” The others are described in similar, pathetic terms.

9 James Nitz, “Happy Felsch,” SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/cd61b579.

10 Eliot Asinof, Eight Men Out (New York: Henry Holt, 1963), 284.

11 Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines (New York: Henry Holt, 1979), 93.

12 Paul Green, “The Later Lives of the Banished Sox,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 22, 1988, 196-97.

13 Westbrook Pegler, “Control, a Little Riser, Were Cicotte’s Secrets,” Kansas City Star, September 28, 1956.

14 Westbrook Pegler, “Onus of Bad Series Finally Made Happy Felsch Sell His Business,” Butte (Montana) Standard, September 25, 1956.

15 Westbrook Pegler, “Swede Risberg Prospers But He Also Suffered; Son a Prospect,” Butte (Montana) Standard, September 26, 1956.

16 If Asinof discovered any other interviews, they are not part of his collection of research notes which is now available to researchers at the Chicago History Museum.

17 Bob Considine, “On the Line,” Waterloo (Iowa) Sunday Courier, January 12, 1947.

18 John Lardner, “Remember the Black Sox,” The Saturday Evening Post, April 30, 1938.

19 “Shoeless Joe’ Jackson Star in Valet Loop Now,” Santa Ana (California) Register, April 7, 1927.

20 “Jackson Applies for Readmission to Pro Baseball,” Florence (South Carolina) News, December 19, 1933.

21 “Baseball Still is ‘First Love’ of Joe Jackson,” Blytheville (Arkansas) Courier News, March 10, 1937.

22 Shirley Povich, “Say It Ain’t So, Joe,” Washington Post, April 11, 1941.

23 “’Shoeless’ Joe Takes Time For Reminiscence,” Blytheville (Arkansas) Courier News, March 9, 1932.

24 As cited in Carney, Burying the Black Sox, 62.

25 There is other credible evidence that White Sox officials were aware of the fix as early as Game One and that Charles Comiskey attempted to inform the National Commission about it (only to be dismissed by American League president Ban Johnson with the famous retort, “That’s the whelp of a beaten cur!”) But Joe Jackson’s request to be benched would be the only known instance of a Black Sox player attempting to inform team officials about the fix during the Series. For a detailed analysis of this episode, see chapter 4 of Carney’s Burying the Black Sox.

26 Scoop Latimer, “Joe Jackson, Contented Carolinan at 54, Forgets Bitter Dose in His Cup and Glories in His 12 Hits in ’19 Series,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1942.

27 “Buck Weaver Asks For Reinstatement,” New York Times, January 14, 1922.

28 Ibid.

29 Jack Brickhouse, with Jack Rosenberg and Ned Colletti, Thanks For Listening! (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1996), 213-14.

30 James T. Farrell, My Baseball Diary (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1957).

31 Pegler, “Control, a Little Riser, Were Cicotte’s Secrets.”

32 Pegler, “Onus of Bad Series Finally Made Happy Felsch Sell His Business.”

33 Pegler, “Swede Risberg Prospers But He Also Suffered; Son a Prospect.”

34 Lyria Williams letter to Katie Jackson, October 16, 1956, Legendary Auctions, Summer 2003 catalog.

35 Bob Hoie telephone interview with the author, July 16, 2012. According to Hoie, who spoke with Fred McMullin’s daughter-in-law twice in 2002, Fred had supposedly written an account of the scandal that was to be given to veteran Los Angeles sportswriter Matt Gallagher after all the Black Sox players were dead. Years later, when Fred’s son Billy asked his mother Delia for the document, she said she had destroyed it.

36 For further discussion on McMullin’s role in the scandal, see the author’s SABR BioProject biography of McMullin at http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7d8be958.

37 “Risberg’s Silence Costs Him Fortune; Landis Locks Door; It’s Too Late Now,” Sioux Falls Argus-Leader, May 23, 1931.

38 “Diamond Outlaw Asks Baseball Heads to Lift Life-time Suspension,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, January 16, 1934.

39 “Reds Rooter Risberg Has Little Hope Now,” Red Bluff (California) Daily News, October 14, 1970.

40 Dwight Chapin, “The Black Sox Scandal: Torn Lives — 50 Years Later,” Los Angeles Times, August 13, 1969.

41 Dwight Chapin, “Gandil Continues to Claim His Innocence,” Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1969.

42 Joe Falls, “Eddie Cicotte — at 81, He’s Proud of Life He’s Led; Family Is, Too,” The Sporting News, December 6, 1965.

43 Ibid.

44 Edward Prell, “Cicotte Had Great Stuff — Schalk,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1969.

45 Associated Press, “Black Sox Scandal Skeleton Still Rattles,” The Oregonian, August 10, 1969.

46 New York World-Telegram and Sun, June 21, 1955. As cited in Brian E. Cooper, Ray Schalk: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009).

47 Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines, 95-97.

48 Ibid.

49 Frank O. Klein, “Catcher Ray Schalk in Huge World Series Exposé,” Collyer’s Eye, December 13, 1919. Schalk was echoing a similar claim made by reporter Hugh Fullerton the day after the World Series concluded. However, Fullerton’s column in the Chicago Herald-Examiner on October 10 did not name the seven White Sox players he claimed “would not be there when the gong sounds next Spring.” Schalk’s interview with Collyer’s Eye was the first to name them.

50 Oscar C. Reichow, “Ray Schalk Never Hinted At Anything Wrong in Series,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1920.

51 Ed Burns, “Unforgettable Memory Left With Schalk by Tears of Black Sox When Told by Comiskey of Banishment,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1940.

52 Rick Huhn, Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2008), 179-83.

53 New York World-Telegram, July 10, 1943.

54 Jim Leonard, “From Sullivan to Collins,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1950.

55 David Bloom, “Dick Kerr, Breaking 17-Year Silence, Tells of ’19 Series,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1937.

56 Tom Meehan, “Hanford’s Jenkins, Black Sox Innocent, Talks of One Big Smirch On Baseball,” Fresno (California) Bee, May 13, 1962.

57 The Scrantonian (Pennsylvania), September 13, 1959.

58 United Press International, “Faber Recalls How Gamblers Were Ruination of White Sox,” Rockford (Illinois) Register-Republic, January 10, 1947.

59 John Lardner, “Remember the Black Sox?” Saturday Evening Post, April 30, 1938.

60 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1984), 222.

61 The World Series was played in an experimental best-of-nine format from 1919 to 1921.

62 Ritter, 301. For Glory, Ritter also interviewed a third member of the 1919 Reds, outfielder Rube Bressler, but they didn’t talk much about the 1919 World Series.

63 Grantland Rice, “Sportlight,” Nebraska State Journal, March 26, 1945.

64 “What’s Become of Sallee? Slim’s Still Tossing,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1944.

65 Earl Wilson, “It Happened Last Night,” Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Morning Herald, June 10, 1952.

66 Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram, March 2, 1937. As cited in Susan Dellinger, Red Legs and Black Sox: Edd Roush and the Untold Story of the 1919 World Series (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006).

67 Dellinger, 326-27.

68 Lee Allen, The American League Story (New York: Hill & Wang, 1962), 100.

69 Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 294.

70 Ritter, 222.