Cuban League

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

Editor’s note: This article was published in 2016.

The popular national sport of baseball maintained and even tightened its hold on the island nation of Cuba in the aftermath of the 1959 socialist revolution. In fact the national game actually expanded in popularity and elevated in talent level during several decades immediately after Fidel Castro’s midcentury rise to power. Once the four-team professional winter league loosely affiliated with North American major-league baseball was shut down after the 1961 season, the door was finally thrown open for establishing a truly island-wide baseball circuit that would feature homegrown talent rather than imported foreign professionals. And this newly revised version of Cuban League baseball would also launch a five-decade domination of international tournament competitions that now stands as the centerpiece of nearly a century and a half of island baseball history. With its novel brand of post-revolutionary “amateur” baseball, Cuba would also develop throughout the second half of the twentieth century a genuine “alternative universe” to better publicized professional circuits represented by the North American and Japanese professional leagues.

The popular national sport of baseball maintained and even tightened its hold on the island nation of Cuba in the aftermath of the 1959 socialist revolution. In fact the national game actually expanded in popularity and elevated in talent level during several decades immediately after Fidel Castro’s midcentury rise to power. Once the four-team professional winter league loosely affiliated with North American major-league baseball was shut down after the 1961 season, the door was finally thrown open for establishing a truly island-wide baseball circuit that would feature homegrown talent rather than imported foreign professionals. And this newly revised version of Cuban League baseball would also launch a five-decade domination of international tournament competitions that now stands as the centerpiece of nearly a century and a half of island baseball history. With its novel brand of post-revolutionary “amateur” baseball, Cuba would also develop throughout the second half of the twentieth century a genuine “alternative universe” to better publicized professional circuits represented by the North American and Japanese professional leagues.

The political estrangement between Cuba and the United States after 1962 not only largely ended the earlier moderate flow of Cuban ballplayers to North American major- and minor-league teams but also cast an aura of mystery over baseball circumstances on the island. North American fans have known precious little over the past five full decades about Cuban baseball developments. Island league stars have thus played in the same virtual obscurity as did the North American Negro Leaguers of the first half of the twentieth century. One obvious result of this isolation from the mainstream North American sporting press is an unfortunate persistence of several widespread myths concerning Cuba’s post-revolutionary baseball era. First and most damaging has been a notion that the level of Cuban baseball diminished dramatically once the professional winter league was scrapped for a new form of “amateur” diamond competition. A related and equally false notion is one suggesting that inferior amateur-level play for the first time replaced superior professional competitions as the central focus of the Cuban national sport.1

Anyone maintaining this latter view overlooks an established historical fact that widespread pre-1950 amateur leagues across the island drew far more interest and produced more native island talent than did the Havana-based pro circuit of the pre-Castro era. The Cuban winter league of the earlier epoch attracted most of its star players from the ranks of imported North American Negro Leaguers, drew a tiny fan following among Cubans living outside the capital city, and produced only a tiny handful of native big leaguers boasting true all-star stature – namely Adolfo Luque (1920s), Orestes Miñoso (1950s), and Camilo Pascual (1960s). It is also indisputable that a half-dozen or more Cuban Leaguers who abandoned the island during the late 1990s and early 2000s for big-league careers in the United States have of late far outstripped the achievements of the small cadre of pre-revolution Cuban major leaguers. Among the new generation of superior Cuban big leaguers originally trained in the post-1962 Cuban circuit we find sluggers Kendrys Morales, José Abreu, Yasiel Puig, and Yoenis Céspedes; flashy infielders Alexei Ramírez, Yunel Escobar, and Adeiny Hechavarría; frontline pitchers Orlando “El Duque” Hernández, José Contreras, Liván Hernández, and fastball phenom Aroldis Chapman. Chapman (recipient of an eye-popping $30 million contract from the Cincinnati Reds in 2010) would launch a heavy recruitment of native Cuban stars (some smuggled off the island by covert human-trafficking operations) that in the second decade of the new millennium produced megadeals for the likes of Céspedes, Puig, Abreu, outfielder Yasmani Tómas, Rusney Castillo, and touted Boston Red Sox minor-league prospect Yoan Moncada.2

The current Cuban League – known as the Cuban National Series – opened its historic 50th season with the first pitch tossed in November 2010. This yearly National Series competition slowly evolved through several distinct manifestations over five-plus decades and has lately undergone further drastic alteration in the past half-dozen winters. While geographically based league teams have always represented provinces (states) or groups of provinces, these league clubs have often changed names from year to year and have only in recent seasons been consistently labeled for a home-base province, with a team nickname attached (e.g., Cienfuegos Elephants, Villa Clara Orangemen, Camagüey Potters). Recent league structure involved 14 provincial teams and two added ballclubs (the Industriales Blue Lions and Metropolitanos Warriors) representing the capital city of Havana.3 There have also been several manifestations along the way of a second (often shorter) Cuban League season. A Selective Series (usually with the 14 provincial clubs combined into eight regional all-star squads) operated in late spring and summer between 1975 and 1995. And an even shorter four- or five-team Super League was staged in June during four early years of the new millennium (2002-2005). Before the idea of the additional Selective Series competition was conceived, a single “Series of the Ten Million” was staged in the early summer of 1970 with six clubs engaged in a marathon 89-game slate. The name for the three-month event was drawn from President Castro’s proclaimed goal of reaching 10 million tons in that year’s sugar-cane harvest, and the series was thus promoted as special entertainment for sugar-industry field laborers.

The Selective Series season played from the mid-’70s to mid-’90s was never considered a true league championship by most island fanatics. It did, however, contribute several highlight moments of Cuban League history and on several occasions provided the longest stretch of the year’s domestic baseball action. During its first nine campaigns the Selective Series was actually longer than the National Series: first 54 games compared with 38 (1975-1977) and then 60 games compared with 51 (1978-1983). Across a final dozen episodes the Selective Series season dipped to 43 contests per team (1984-1985), ballooned out to 60 games (1986-1992), then shrank again to 45 (1993-1995). It was during this competition in 1980 that Cuba celebrated its first .400-plus hitter (Héctor Olivera, Las Villa, .459 – father of the future “defector” and big leaguer of the same name); Omar Linares did not reach that plateau in the National Series until five years later. It was also in the Selective Series that Orestes Kindelán produced the first 30-plus home-run total (30 in only 63 games), with Alexei Bell not reaching that same milestone in the National Series until as late as 2008 (31 in 90 games). The Selective Series also provided seven of the island’s 51 rare no-hit, no-run pitching performances.

The half-dozen even shorter “second” seasons played during the past several decades – after the Selective Series tradition was finally scrapped – proved even less successful and therefore less sustainable. Two Revolutionary Cup campaigns in the 1990s (both won by Santiago de Cuba under manager Higinio Vélez) were memorable for a handful of individual record-setting performances and little else. Both 30-game events produced .450-plus batsmen (Yobal Dueñas, 1996, and Javier Méndez, 1997) and Santiago’s Ormari Romero claimed 14 pitching victories without defeat across the same stretch. The four-year Super League experiment was an even larger failure although it did witness a playoff no-hitter tossed for Centrales by Maels Rodríguez. The idea of having provincial teams combined into a smaller number of regional squads never gained much traction with island fans. Super League games also fell during the hottest (and wettest) part of the year, and most games staged in the month of June were played to empty stadiums and disappointingly sparse television viewership.

Failure of these experimental extra seasons to garner any true fan enthusiasm is largely explained by a unique feature of island baseball that is also the basic strength of Cuban League structure. Since league teams are government properties overseen by a national sports ministry (INDER, National Institute of Sports, Education and Recreation) – not corporate businesses run for profit – there is no trading or transferring of Cuban League players, with all athletes serving on teams representing their own native province.4 Like all Cuban athletes, ballplayers rise through the ranks of regional sports academies, performing for their neighborhoods on various age-group youth clubs and eventually graduating to Developmental League (the Cuban minors) and National Series teams. With the rarest of exceptions, a Cuban League star spends his entire playing career with a single local ballclub. The huge plus sides of this unique system are both the deep-seated loyalties between fans and players and the rabid fanaticism attached to local clubs that truly do represent a fixed geographical locale. (A big-league equivalent would be a Boston Red Sox club employing only players raised and trained in the New England region.) The downside, of course, is that the Cuban League – like the majors in the era before free agency – is not exceptionally well balanced. Larger provinces enjoy heftier talent supplies and thus usually better teams; Havana and Santiago teams (along with occasional inroads by Pinar del Río and Villa Clara) have dominated championship play throughout league history.

Because of such hometown fan loyalties and attachments to local stars, shorter seasons with fewer teams have failed to garner support, if only because the teams playing are not the usual fan favorites. Seeing the local heroes attired in strangely colored uniforms and competing for strangely named squads has little appeal for rooters attached by birthright and home base to Industriales, Pinar del Río, or Sancti Spíritus. What might Boston Red Sox fans make of any two- or three-month season featuring Sox players joining forces with Yankees, Mets, and Phillies stars on a team now relabeled as the Eastern Seaboard Lions? Fanaticism based on long tradition – and in Cuba also on the concept of local neighborhood stars – disappears in a league featuring several months of what are widely perceived as mere all-star exhibition contests.

National Series play was inaugurated in mid-January of 1962 and involved only a handful of teams during its earliest campaigns. Players were drawn from all areas of the island, but the initial clubs known as Occidentales, Azucareros, Orientales, and Habana played the bulk of their first-season 27-game schedule in Havana’s spacious Cerro Stadium (home of the pro winter circuit in the 1950s, rechristened as Latin American Stadium in 1971, and still in use today). The concept initially mandated by the new Castro government was to replace commercial baseball with dedicated amateur play, designed to promote public health rather than financial profit (for either athletes or franchise owners) and thus more in line with a socialist spirit of government at the heart of a revamped societal system. In early seasons the players were indeed true amateurs, and the lower level of early league play reflected that fact. The first few seasons were short, and ballplaying was not yet a full-time occupation for league athletes, who also maintained other professional occupations in the newly minted socialist society.

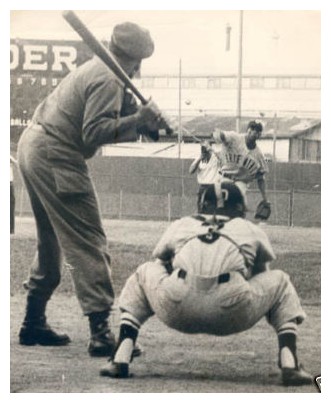

The historic initial season staged in the spring of 1962 lasted for little more than a full month and followed by less than nine months a clandestine US-backed invasion attempt at the Bay of Pigs. A future league ballpark in the city of Matanzas (Victory at Girón Stadium) would eventually carry the name of the landmark 1961 invasion that solidified the Fidel Castro-led revolutionary government. An opening set of league games was celebrated in Cerro Stadium before 25,000 fans on Sunday, January 14, 1962. President Castro provided a lengthy speech and then stepped to the plate in his traditional military garb to knock out a staged ceremonial “first hit” against Azucareros starter Jorge Santín. When the actual ballplayers took the field, Azucareros blanked Orientales 6-0 behind three-hit pitching from Santín. In an 11-inning nightcap, Occidentales edged Habana 3-1 with ace Manuel Hernández striking out 17 enemy batters.5 A widely reprinted photograph of President Castro stroking the season’s first base hit delivered by Azucareros pitcher Modesto Verdura (not Santín) actually occurred in the same park on Opening Day of National Series II later in the same calendar year.

Four clubs participated in the initial monthlong season, one managed by former big leaguer Fermín Guerra (Occidentales) and a second (Azucareros) directed by the former skipper of the minor-league Cuban Sugar Kings, Tony Castaño. Occidentales under Guerra captured the first short-season title with the circuit’s only winning ledger, and Occidentales outfielder Edwin Walter reigned as the first batting champion. The popular Havana-based Industriales ballclub was organized for the following second season, which was the first to begin in the month of December and thus the first to overlap two calendar years. Industriales – the longest existing and most successful league team – would immediately launch its proud tradition by claiming four straight league titles in its initial four years of league play.

Early successes of the Cuban national team during the first decade of Fidel Castro’s administration would soon redirect league structure and philosophy toward the development of strong national squads that could use baseball as something of a governmental foreign-policy tool. A string of eight straight Amateur World Series titles in the 1970s demonstrated that Cuban baseball squads could score strong propaganda victories by beating the North Americans (and also the Asians and rival Caribbean neighbors) at their own game. Baseball was, after all, also the long-standing Cuban national sporting passion and therefore very much a national pastime shared with the rival Americans.6 As a result of the new Cuban emphasis on victories abroad in Olympic-style events, government sports academies soon flourished around the island, and Cuban athletes graduating from those institutions became full-time practitioners of their assigned sporting activities. Thus athletes were financially supported – even if at a modest level by North American standards – and they became “professionals” in at least two different senses of the word. Cuban ballplayers are now paid for performance, and consequently they devote all their effort and attention to their assigned profession of ballplaying.7

Early successes of the Cuban national team during the first decade of Fidel Castro’s administration would soon redirect league structure and philosophy toward the development of strong national squads that could use baseball as something of a governmental foreign-policy tool. A string of eight straight Amateur World Series titles in the 1970s demonstrated that Cuban baseball squads could score strong propaganda victories by beating the North Americans (and also the Asians and rival Caribbean neighbors) at their own game. Baseball was, after all, also the long-standing Cuban national sporting passion and therefore very much a national pastime shared with the rival Americans.6 As a result of the new Cuban emphasis on victories abroad in Olympic-style events, government sports academies soon flourished around the island, and Cuban athletes graduating from those institutions became full-time practitioners of their assigned sporting activities. Thus athletes were financially supported – even if at a modest level by North American standards – and they became “professionals” in at least two different senses of the word. Cuban ballplayers are now paid for performance, and consequently they devote all their effort and attention to their assigned profession of ballplaying.7

Over the course of its opening decade the National Series expanded to first six teams (1966) and eventually an even dozen ballclubs (1968). The number of games for each club also surged to 65 by mid-decade (1966) and eventually to as many as 99 (1968). The league reached its full stride once all provinces were represented by the mid-’70s and once postseason playoffs were introduced for the 1985-86 season as a pressure-packed means of determining an eventual league champion. As the ever-changing league evolved in size, it also regularly changed in shape, with a division into two groups or “zones” after 1988, and then four groups after 1993. The two-division structure – with a Western League (Occidental) and Eastern League (Oriente) – was once again adopted with the recent 2007-2008 season, and a 90-game schedule has been the league standard since National Series #37 (1997-98). But with a decision in 2012 to divide the season into two 45-game segments, the league reverted to a single 16-team operation with only eight qualifying for the second-half championship round. Division structure was thus abandoned after National Series #51 (2011-12).

Cuba’s postseason playoffs have now witnessed more than a quarter-century history of their own and in many respects mirror their counterparts in the big leagues. Until the recent split-season transformation, for a decade-plus the postseason featured quarterfinal (five games), semifinal (best-of-seven), and final series (also seven games). But beginning in the spring 2013 the new format eliminated one postseason round since only four second-half clubs were playoff qualifiers. The one major departure from major-league postseason performance derives from the practice in the Cuban circuit of counting a player’s individual statistical record as part of his cumulative career totals. Individual pitching and batting titles are determined before the postseason fray commences, but the record 487 lifetime homers of Orestes Kindelán and the career .368 batting standard of Omar Linares do indeed include playoff numbers. Recent campaigns have featured a host of thrilling seven-game final-round confrontations that have gripped the nation’s television and radio audiences in early springtime. Just as big-league championships match American and National League rivals, the finals in Cuba traditionally included the top surviving clubs representing the eastern and western zones of the island. (That went away once the single league structure emerged in 2012.) The island’s top fan favorites, Havana-based Industriales, squared off in the winner-take-all conclusion with one of their two western-sector heated rivals – either Santiago or Villa Clara – on five different occasions in the first decade of the new millennium.

The new National Series structure of the early 1960s not only spread organized league baseball island-wide for the first time, but it also extended and expanded a tradition of popular “amateur” leagues which had been at the center of the nation’s baseball since its origins in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Amateur-level baseball had always been the island’s most popular sporting tradition and thus did not suddenly take hold – as popularly misconstrued – only with the Castro-led revolutionary government of the early ’60s. Throughout the century’s first five decades it was not the racially integrated Havana pro circuit but rather the more geographically diverse and all-white amateur league that drew both the largest fan followings and the island’s top athletic talent. Many skilled players choose to remain amateurs since amateur teams ironically offered greater financial rewards (lucrative jobs with sponsoring corporations such as the national electric company or telephone company) and easier playing conditions (games played only on weekends). Today’s government-run Cuban baseball enterprise is admittedly more commercial in nature; yet it now draws its distinctive “amateur” flavor from the complete absence of any profit-motivated corporate team ownerships or ballplayer “free agency” of the type defining pro circuits in North America, Europe, or Asia.

Cuban throwback-style ballparks are today one of the league’s most charming features with their natural-grass surfaces, absence of concession stands, minimalist nonvideo scoreboards, concrete bleachers, and bulky concrete electric-light stanchions. Most parks were built in the ’70s and have a nearly identical appearance; construction crews were drafted from the island’s population of students and field workers to erect these structures as part of the government’s widespread public-works projects of that era. Many stadiums are named for late-’50s revolutionary military heroes or important revolutionary battle sites, but two were christened to honor star league pitchers tragically lost in 1970s-era automobile accidents. The former include Capitan San Luis (Pinar del Río) and Nelson Fernández (San José de la Lajas); the latter are José Antonio Huelga (Sancti Spíritus) and recently abandoned Santiago “Changa” Mederos (Havana). The current 16 league teams are housed in stadiums located in the capital city of each province, but most clubs also play a small portion of their league contests in smaller ballpark venues found in outlying provincial villages.

One historic older venue is Latin American Stadium, housed in the Cerro (“hill”) district of Havana. The park was constructed in 1946 and is thus a holdover from the pre-revolution professional circuit that operated in the capital city through 1961. The last decade of that circuit found almost all league games staged in the building that was then known as Cerro Stadium or Gran Stadium. The structure received a major expansion and renaming in 1971 when the country hosted one of the numerous Amateur World Series events played in the capital city. The Havana Cubans (Class-B Florida International League, 1946-1953) and the Cuban Sugar Kings (Triple-A International League, 1954-1961), two minor-league clubs affiliated with Organized Baseball in the ’40s and ’50s, also called this historic structure their home. Completely enclosed during its 1971 renovation, today’s Latin American Stadium boasts more than 55,000 seats in its slowly deteriorating single-deck structure of covered grandstand and open-air bleachers.

Contemporary Latin American Stadium (familiar dubbed “Latino”) features much the same appearance and aura it offered a half-century back, although the grandstand roof and home-plate area box seats have fallen into more than slight disrepair. The sprawling park has served for several decades as home to both capital city league clubs, Industriales and the now defunct Metropolitanos (more popularly called Metros). By the 2009 season, however, the also-ran and less popular Metros team was playing exclusively at the smaller-capacity Changa Mederos Stadium, located in the Havana Sports City athletic training facilities. Renovations were again done to Latino in advance of a Baltimore Orioles exhibition game versus the Cuban national team staged during late March 1999; MLB-quality outfield wall padding was provided by Major League Baseball as part of that historic exchange. A new scoreboard utilizing solar power and designed to cut usage of precious electricity was also imported from Vietnam and installed for the opening of a historic Golden Anniversary National Series in November 2010. Several mid-2000s seasons in Havana had featured only daylight play due to damaged light towers (at both Latino and Changa Mederos) and an island-wide effort to conserve electricity in the face of the island’s growing economic crisis.

Colorful team nicknames are also today a special feature of the Cuban League scene, although they were rarely used by the Cuban press until the final decade of the twentieth century when they became a regular feature of media coverage on the island. Current teams are actually named for the provinces that host them and not for provincial capital cities, which in most cases carry the same name. This has been the norm since the mid-’80s, but earlier club monikers often differed from provincial labels, occasionally indicated occupations sometimes overlapping with current club nicknames, and sometimes changed rapidly from year to year. The ’60s featured squads called Occidentales, Orientales, Granjeros, and Azucareros (Sugar Harvesters); the ’70s witnessed clubs labeled Mineros (Miners), Oriente, Henequeneros, Constructores, and Serranos; the ’80s introduced Camagüeyanos, Citricultores (Citrus Workers), and Vegueros (Tobacco Harvesters).

Recent-Era Cuban League Team Names and Principal Stadiums

Occidental (Western) League

| Team | Principal Stadium |

|---|---|

| Industriales Leones (Blue Lions) | Latinoamericano |

| Pinar del Río Vegueros (Tobacco Farmers) | Capitán San Luis |

| *Habana Province Vaqueros (Cowboys) | Nelson Fernández |

| Sancti Spíritus Gallos (Roosters) | José Antonio Huelga |

| Cienfuegos Elefantes (Elephants) | Cinco de Septiembre |

| Matanzas Cocodrilos (Crocodiles) | Victoria de Girón |

| Isla de la Juventud Piratas (Pirates) ** | Cristóbal Labra |

| Metropolitanos Guerreros (Warriors) * | Changa Mederos |

| Artemisa Cazadores (Hunters) * | 26 de Julio |

| Mayabeque Huricanes (Hurricanes) * | Nelson Fernández |

Oriente (Eastern) League

| Team | Principal Stadium |

|---|---|

| Santiago de Cuba Avispas (Wasps) | Guillermón Moncada |

| Villa Clara Naranjas (Orangemen) | Augusto César Sandino |

| Ciego de Avila Tigres (Tigers) | José Ramón Cepero |

| Las Tunas Leñadores (Woodcutters) ** | Julio Antonio Mella |

| Camagüey Tinajones (Potters) | Candido González |

| Guantánamo Indios (Indians) | Nguyen van Troi |

| Granma Alazanes (Stallions) | Martires de Barbados |

| Holguín Cachoros (Cubs) | Calixto García |

*Provincial realignment eliminated Habana Province and introduced Mayabeque and Artemisa for the 2011-12 league season. The Havana Metropolitanos team was disbanded at the end of that same campaign.

** The Isla de la Juventud ballclub was known as Pine Cutters until recent campaigns and Holguín recently switched its name from Perros (Dogs) to Cachorros. Las Tunas was earlier known as the Magos or Magicians.

Havana’s Industriales Blue Lions remain the island’s most popular club, not surprisingly since that team represents the capital city region boasting a third of the nation’s population. This team and its rabid following was the subject of the award-winning Cuban documentary (Fuera de la Liga, 2006) by Ian Padrón that took top prize at the 2009 Cooperstown film festival competition. The Industriales ballclub has also enjoyed the greatest championship success: The Lions have claimed a dozen title banners, four more than the Santiago de Cuba ballclub representing the island’s second most populous region. Former New York Yankees pitching star Orlando “El Duque” Hernández and 2000s California Angels, Seattle Mariners, and Kansas City Royals slugger Kendrys Morales both began their stellar careers on the Industriales roster. It is popular folklore in Havana that revolutionary war hero Ernesto “Che” Guevara was instrumental in the club’s founding on the eve of National Series II (1962-1963), but that myth has no demonstrated factual basis.

Cuban baseball of the modern post-revolution era is characterized by two unique features – the league’s geographical rather than corporate structure, and the fact that athletes traditionally have performed for regional teams during the entire duration of their careers. Ballclubs representing provinces and not private corporate businesses mean intense fan loyalties, since one’s local team always consists of strictly hometown athletes. This feature of fan loyalty is intensified by the fact that Cuban ballplayers are never sold or traded from one ballclub to another, thus performing their entire careers with the hometown squad.8 One consequence of such regional structure is the aforementioned imbalanced competition, since more populous regions enjoy far greater access to ballplaying talent. But the absence of team parity seems more than canceled out by the promise of passionate regional competitions.

Cuban baseball of the modern post-revolution era is characterized by two unique features – the league’s geographical rather than corporate structure, and the fact that athletes traditionally have performed for regional teams during the entire duration of their careers. Ballclubs representing provinces and not private corporate businesses mean intense fan loyalties, since one’s local team always consists of strictly hometown athletes. This feature of fan loyalty is intensified by the fact that Cuban ballplayers are never sold or traded from one ballclub to another, thus performing their entire careers with the hometown squad.8 One consequence of such regional structure is the aforementioned imbalanced competition, since more populous regions enjoy far greater access to ballplaying talent. But the absence of team parity seems more than canceled out by the promise of passionate regional competitions.

Two other special features of the Cuban League also demand emphasis. One is the fact that only native-born Cuban athletes perform in the league, making it the purest example of a homegrown sporting production. The practice is in line which INDER’s goal of shaping league seasons for the express purpose of training and selecting national team players. No other top circuits can boast this type of rigidly nationalistic flavor. Another oddity of league play (at least in view of traditions in Organized Baseball) is the practice of considering career statistics for individual ballplayers to be a composite not only of National Series games, but also of Selective Series, Revolutionary Cup, and Super League contests. And as earlier noted, batting and pitching stats accumulated during postseason play (in effect for the past three decades) are also counted in a ballplayer’s final career numbers.9

The most defining element of Cuban League baseball, however, remains the mere fact that championship seasons exist with a primary purpose of training and selecting national team rosters for top-level international competitions. Since the 1960s the focus of Cuban baseball has always been on capturing international championships and thus fostering the nation’s celebrated socialist-style sporting image. Cuba’s national teams have as a result dominated international baseball for a half-century and counting (since the early ’60s) and have in the process established a winning ledger that is easily the most remarkable in the history of the sport at any level. The most noteworthy feat has been Team Cuba’s five-decade string of either winning or at least reaching the championship game of more than 50 consecutive major international tournaments (53 events in total). This unparalleled streak finally came to an end with a second-round ouster of Team Cuba at the 2009 World Baseball Classic. Between the 1987 Pan American Games in Indianapolis and the 1997 Intercontinental Cup matches in Barcelona, the Cuban squad also claimed victory in 159 straight games played during major IBAF (International Baseball Federation) tournaments. Over five full decades Cuban teams maintained their dominance by capturing three gold and two silver medals in the five “official” Olympic baseball tournaments, as well as walking off with 18 of the 23 championship banners contested in the IBAF Baseball World Cup matches. Despite a recent dip in performance after the final IBAF World Cup event in 2011, Team Cuba’s overall game-winning percentage since 1962 still stands well above 90 percent.

Cuban baseball did experience its own brief game-fixing scandal in the early ’70s, though the affair was rather minor in scope when compared to the infamous big-league Black Sox affair or the widespread corruption that nearly sank the Taiwanese pro league in the late 1990s. The hushed-up Cuban event received no media coverage on the home island at the time and involved a contingent of Industriales players who were suspended in the late 1970s without any public admission of guilt. Among the banned was promising star infielder Rey Anglada, whose 10-year career was cut short by the affair. Another was slugger Bárbaro Garbey, a former league batting champion (Selective Series, 1976) and RBI leader (National Series, 1978). Garbey left Cuba in the celebrated 1980 Mariel Boatlift and eventually showed up in North American professional baseball (which seemed to find his alleged misdeeds acceptable since they were easily dismissed as a blow against an enemy Cuban government).10 Garbey quickly proved a big-league misfit while Anglada quietly served out two decades of rehabilitation at home and then resurfaced in the early 2000s as a remarkable Cuban League managerial success story. Anglada would eventually direct his former Industriales club to three league pennants and also claim both silver (IBAF World Cup) and gold (Pan American Games) medals as the 2007 bench boss for the Cuban national team.

The Cuban League has been especially noted for numerous unmatched individual performances, some rarely if ever duplicated in the world’s other top professional circuits. One of the most noteworthy has been the home-run-hitting exploits of Santiago outfielder Alexei Bell, who blasted a record seven bases-loaded home runs in the league’s short 90-game schedule during National Series #49 (2010). Bell’s feat of launching the 2009-2010 season with remarkable consecutive grand slams in the initial inning of the season’s lidlifter game may be the single most memorable moment in league annals. Another noteworthy slugging display in the new millennium has been the long-ball hitting of Granma star Alfredo Despaigne, who established a single-season mark for home runs (32) in 2009 (one better than Bell a year earlier) and then repeated the feat in 2012 by upping the mark to 36. Perhaps more remarkable still were the five consecutive batting titles of Las Tunas outfielder Osmani Urrutia. Between 2001 and 2005 Urrutia compiled an unearthly five-year composite batting average above .400 (.422), a feat approached in North American major-league competition only by Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby (.402, 1921-1925).

While many Cuban league records seem suspect to North American fans because of lesser talent, shorter seasons, and several decades of aluminum bats, there are some individual performances that have no true major-league equivalents. In addition to his single-inning grand slams, Bell holds two other distinctions, one being a pair of single-inning homers in a playoff game (April 18, 2007) and the second involving another postseason single-inning three-hit outburst (April 5, 2008). A player striking two homers in a single inning has occurred on several occasions in the majors (and 25 times in the Cuban League); three hits in an inning has been achieved but twice in the majors (Gene Stephens and Johnny Damon). But neither rarity has ever occurred during MLB playoff games. Still another unparalleled Cuban League event is the 14 consecutive hits by Granma’s Ibrahim Fuentes (1989), which outdistanced by two the 1952 big-league mark of Walt Dropo. A third unrivaled Cuban landmark would have to be the 22-strikeout game by Faustino Corrales, two above the big-league record posted on five occasions (twice by Roger Clemens and once each by Kerry Wood, Randy Johnson, and Max Scherzer). Also in contention for special recognition are the 63 career shutouts achieved by Braudilio Vinent, which match the live-ball-era major-league standard of Warren Spahn. Yet Vinent reached the figure in only about one-third the number of starts required by Spahn. Spahn logged 665 starts across his 21 Boston and Milwaukee campaigns (thus one shutout every 10.5 starts); Vinent reached the same total during his 20 years of combined National Series and Selective Series seasons in a mere 400 starts (meaning one shutout every 6.3 starts). Both recorded single-season highs of seven (Vinent in the 1973 National Series, Spahn in both 1947 and 1951), but again Santiago’s Vinent seems to hold the edge here since Cuban seasons are briefer and thus a pitcher’s game-starting opportunities are far fewer.

No-hit games are as much a cherished rarity in Cuba as they are in the majors, and by at least one measure they are a much rarer phenomenon. The league witnessed only 51 no-hitters (one per year) through December 2010, the last one thrown by Pinar’s Vladimir Baños only several weeks into the historic 50th National Series season. Granted that Cuban League seasons are only slightly more than half as long as are big-league campaigns, and twice as many ballclubs in the two MLB circuits also mean approximately twice the number of daily games. Nonetheless, the modern major leagues produced (by the finish of the 2010 season) a grand total of 269 “official” nine-inning gems or an average of 2.5 per season. And this number includes only “sanctioned” no-hitters in which a game must last a full nine innings and the pitcher authoring the gem must also be the game-winner. If we add in no-hitters tossed in losing efforts (there have been three), weather-shortened gems of less than nine frames (there have been 23 since 1903), plus games in which no-hitters were broken up in extra innings, after the first nine frames were hitless (13 of these), then the pre-2011 major-league total soars to 308 and the ratio to 2.878 major-league no-hitters per season. Of 50 Cuban National Series through 2011, only a mere three (those ending in 1968, 1969, and 2000) witnessed as many as three different no-hit efforts. There has only been one perfect game (without a single baserunner) in the Cuban League (tossed by Maels Rodríguez on December 22, 1999), again making this event even rarer on the Cuban island than in the majors.

One no-hit-related event in Cuba stands out for special mention. The first pair of such games were thrown back in 1966, during successive starts by otherwise unheralded right-hander Aquino Abreu. Abreu, a lifetime sub-.500 hurler at 63-65 over 14 seasons (1962-1975), thus became the only pitcher in any major national professional league to match Cincinnati’s Johnny Vander Meer (1938) with consecutive no-hit masterpieces. The first Aquino whitewash came on January 16, 1966, at Augusto César Sandino Stadium (Villa Clara) during the opener of a four-team doubleheader. Abreu (pitching for Centrales) permitted five baserunners (including a hit batter in the ninth) yet blanked Occidentales 10-0 without permitting a single safety. Nine days later the feat was repeated with a 7-0 blanking (marred only by five free passes) against Industriales in Havana’s Latin American Stadium. An added historical irony attached to Abreu’s back-to-back masterpieces is that they were also the first two such games witnessed in Cuban League action.

When discussing pitching and batting feats on the island nation, Cuba’s half-century-long league history might best be viewed as three distinguishable epochs. First to unfold was Cuba’s version of the Deadball Era, which extended across nearly two decades into the late 1970s. Batting feats remained unimpressive and pitching marks were eye-popping, especially ERA totals. Eight league leaders in the latter department posted sub-1.00 figures across the first 15 National Series seasons, while only one slugger (Armando Capiró, 1973) was able to top the 20-homer plateau. Next came the upsurge in offense brought by the 1977 introduction of aluminum bats. This era lasted a full two decades until 1999 and the reintroduction of the wooden bat. The later event came at the time of the Baltimore Orioles’ exhibition visit in March 1999 and was spurred by changes in equipment rules for international tournament play. During this second era, slugging exploded, paced by the home-run bashing by Kindelán and the all-around offensive prowess of Omar Linares, who batted above .425 on three occasions. The third and final era, post-2000, has witnessed an even bigger onslaught on the batting entries in league record books. But this latter surge likely has been due to increased league-wide athletic talent as much as to any changes in equipment or playing conditions. By 2010 (a decade after the change) only three sluggers – Joan Carlos Pedroso in February 2009 and Yulieski Gourriel and Frederich Cepeda in January 2010 – had reached 200 or more homers playing only with major-league-caliber bats, but four more would get there in the past half-dozen years (Alfredo Despaigne, Eriel Sánchez, Alexander Malleta, and Yosvany Peraza) to 2016.

North American fans at all aware of Cuban baseball are seemingly most intrigued with the issue of Cuban ballplayer “defections” to the North American pro ranks, although before 2010 this was a subject much overblown in the foreign press while at the same time almost never discussed by Cuban media. The percentage of young prospects leaving the island began soaring near the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century as economic conditions worsened in the homeland. But the fact remained that until 2010 few recognizable stars abandoned the socialist baseball system, and thus the impact on the level of league play was quite minimal.11 Cuba long evaded the fate of all other Caribbean hotbeds (Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and especially Puerto Rico) which have been essentially stripped clean of their local baseball operations by the constant transfer of homegrown talent to the higher-paying North American majors and minors. All changed after 2010 when the slow trickle became first a steady leak (Aroldis Chapman 2009, Leonys Martin 2010, Yoenis Céspedes 2011, Yasiel Puig 2012, and José Abreu 2013 among the headliners) and finally a floodtide (with nearly 150 Cuban League escapees in late 2014 and throughout 2015). Many of the hair-raising departures involved most unsavory tales of human trafficking violations and life-threatening scenarios for athletes and their families, as thoroughly examined in my 2016 book Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story.

The three most talented and celebrated Cuban Leaguers of the past half-century have (by wide consensus) been Omar Linares, Orestes Kindelán, and Pedro Luis Lazo. Linares was repeatedly labeled across two decades as the top all-around third baseman performing anywhere outside the major leagues. “El Niño” Linares’s top career achievement may well have been a career slugging percentage (.644) outdone only by Babe Ruth in the big-league record books. Kindelán’s home-run slugging was legendary both on the island and in the realm of international tournaments. His career highlight came with 30 homers in only 63 games during a short Selective Series season. At the Atlanta Olympics the oversized DH belted the longest fly ball (a homer into the third deck in left-center field) ever witnessed in Fulton County Stadium (former home of the Atlanta Braves). There has never been a Triple Crown winner in National Series play, but Kindelán came tantalizingly close on several occasions.12 Lazo retired in December 2010 as Cuba’s all-time most successful hurler with a record 257 victories and 2,426 career strikeouts (only 73 short of Rogelio García on the all-time list). On the international scene “The Cuban Skyscraper” was a dominant closer who grabbed the attention of North American audiences during the first World Baseball Classic.

The slugging feats of Linares and Kindelán seem now somewhat muted by their career-long use of the aluminum bats that were employed in Cuba from 1977 through 1999. And younger sluggers like Alfredo Despaigne and José Dariel Abreu by 2010 were already threatening many of their cherished records, Abreu missing out on a Triple Crown on the season’s final day in 2011 and Despaigne setting single-season home-run marks and at least temporarily overhauling Linares’s hefty career slugging numbers. Lazo is more likely to maintain his fame over the long haul in Cuba due as much to his colorful image and charismatic character as to his mere statistical legacy. In the final years of his storied career, Lazo became a fixture of televised league games, regularly captured by cameras while leaning on the dugout or bullpen railing puffing on a huge cigar during live game action.

Another contemporary Cuban League figure who deserves note is veteran Isla de la Juventud hurler Carlos Yanes, one of the most remarkable “iron men” in the long annals of the sport. Completing a remarkable 28 league seasons, Yanes achieved feats unprecedented in modern era play. The Isla de la Juventud right-hander has few parallels as both a winner and loser of more than 200 games, and at the outset of the 2010-2011 campaign he continued to maintain hope of overtaking Pedro Lazo’s career victory mark; to reach that goal (he eventually fell 18 short), the breaking-ball specialist would have had to remain active beyond 30 campaigns (also beyond the ripe age of 50). Despite the shorter Cuban seasons, the crafty junkball hurler (235-242 at career’s end) nonetheless also fell only a shade short of the unique career won-lost ledger of big leaguer Jack Powell (245-254), the sub-.500 MLB 200-game-winner with the largest number of both wins and losses. Had Yanes only pitched for a more successful ballclub (like Villa Clara or Santiago), he would likely own all the Cuban career marks. As it is, the durable 46-year-old athlete bowed out at the top of a dozen categories, most of them attached to remarkable feats of mere durability.

Like any top professional leagues, Cuba’s has produced its own collection of memorable and talented managers. National Series play serves as a proving ground for the selection of national team managers and coaches as well as national team ballplayers, and thus a handful of the top skippers have eventually distinguished themselves in international tournament play. The most noteworthy in this group are perhaps Servio Borges, Higinio Vélez, and Jorge Fuentes. Borges was the most successful among the early 1970s school of coaches trained entirely in a revamped revolutionary baseball system introduced by Fidel Castro’s sweeping governmental and social reforms; he also presided over the mid-’70s transition from wooden to aluminum bats. In addition to guiding eight championship squads in Amateur World Series play over a dozen summers (1969-1980), Borges also claimed two National Series crowns with Azucareros (1969, 1972). Vélez was only briefly visible to North American fans as Cuba’s manager during the first two editions of the MLB-sponsored World Baseball Classic. In domestic league action, the most successful at winning championships over the long haul has been Jorge Fuentes in Pinar del Río, a five-time championship manager. Two skippers (Vélez and Pedro Jova) have strung together back-to-back-to-back league titles, and two others (Antonio Pacheco and Rey Anglada) have claimed three titles in four campaigns. But only one bench boss – Ramón Carneado – has claimed four pennant victories in a row. The legendary Carneado worked his magic with Havana’s Industriales club at the dawn of the new league (1963-1966) when most of his players were truly part-time amateurs. More recently, Victor Mesa, an all-star outfielder of the 1980s, proved to be the island’s most colorful and also controversial manager while serving at the helm in Villa Clara from the mid-1990s to late 2000s, and then again in Matanzas after 2012. Mesa (before his dismissal from Villa Clara in 2009) was known for such stunts as ejecting his entire relief corps from the bullpen to the team bus during an opposition rally, berating his bench between innings in full view of television cameras, replacing one pinch-hitter with another in mid-count of an at-bat, and substituting one pinch-runner for another after a successful steal by the first substitute. Many on the island complained that Mesa hurt his squads by always attempting to attract more attention to himself than his players (while others saw that same trait as a huge plus). Mesa also earned considerable attention off the island as manager of the powerful Cuban entry at the most recent edition (2013) of the World Baseball Classic.

Even before the arrival on the stateside scene of recent headliners like Chapman, Puig, Abreu, and Céspedes, the Cuban League of recent decades, despite its isolation, spawned a small but noticeable number of big leaguers – especially pitchers. These players “defected” from their homeland for various personal (and not always strictly financial) reasons. René Arocha was the first of the modern-era national team stars to escape Castro’s baseball empire, doing so in the aftermath of a July 1991 exhibition series in Millington, Tennessee. Two half-brothers – Liván (with the 1997 world champion Florida Marlins) and Orlando Hernández (with the 1998 world champion New York Yankees) made their marks on major-league postseason lore in the late ’90s. José Contreras was a major star on the Cuban national team – posting a perfect 13-0 international record – before joining the Yankees in 2003. More recent refugee hurlers have been Chapman (Cincinnati Reds) and Yunieski Maya (Washington Nationals), both debuting with the pros in 2010. Southpaw Chapman gained much press attention with his 100-plus-mph fastball (surpassed in the speed department back in Cuba only by Maels Rodríguez), but Maya, number-two national team starter and 2005 league ERA champion, was perhaps a far greater loss – to both the home league and Team Cuba fortunes in international play. One nonpitcher enjoying early twenty-first-century successes in the big time was California/Anaheim Angels first baseman Kendrys Morales (whose career stretched on with Seattle and Kansas City). Morales exploded on the Cuban scene in 2003 as National Series rookie of the year but abandoned the island only three years later. The switch-hitter finally enjoyed a true breakout season with the American League Angels in 2009 (34 HR, 108 RBIs), but only after a long trial in the North American minor leagues.

Many top Cuban stars of recent decades have ranked among the world’s best ballplayers, despite never showcasing their talents in the professional North American major leagues. Pinar del Río mainstay Omar Linares – the Cuban League career batting leader with a lifetime .368 average compiled over 20 National Series and Selective Series seasons – was for two decades considered the world’s best “amateur” player and the “greatest third baseman never to appear in the major leagues.” And the inaugural three renditions of the World Baseball Classic (2006, 2009, 2013) demonstrated that Cuban League all-stars can easily match major leaguers in top-level tournament competitions. Cuba surprised the professional baseball world by reaching the finals of the initial event, while switch-hitting outfielder Frederich (Freddie) Cepeda was both batting leader and the only unanimous all-star selection at the 2009 second-edition Classic. And Granma Province slugger Alfredo Despaigne established an all-time home-run mark (11 in 15 games) while leading the Cuban national squad to the finals of the 2009 IBAF Baseball World Cup in Europe.

A drastic overhaul of Cuban League structure took place in the fall of 2012 on the eve of National Series #52, with the decision to scrap divisional structure in favor of a single 16-team league and also to divide the campaign into two distinct segments of 45 games each – an initial qualification round with the traditional 16 teams, followed by a championship round featuring only eight surviving clubs. Eight top players from each of the bottom (eliminated) squads would hence be awarded in a supplemental player draft at midyear to the second-round teams. The major impact here was the loss of the long-standing tradition of athletes only performing with the home province; still another more impactful result was the fact that half the provinces were suddenly left without baseball for more than half the league calendar. There was a dual motive for the chance, the first being the effort to shore up recently sagging national team fortunes by providing a more competitive league (for at least part of the year) with the island’s top pitchers clustered on fewer rosters. But equally at play was the reality that the Cuban Federation was finding it increasingly difficult to shoulder the cost of transporting 16 teams around the island for six months and lighting stadiums for night games in each and every province.

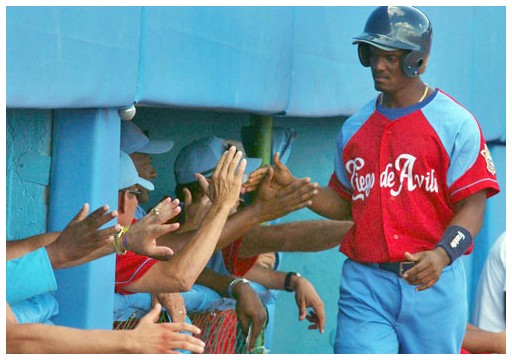

As of 2016, two teams have dominated the past half-dozen seasons with longtime doormat Ciego de Avila claiming three titles under manager Roger Machado, more traditional power Pinar del Río tasting victory twice, and Villa Clara walking off with the first title earned under the novel split-season format. A second novel development on the Cuban League scene has been the return of the league champion to the February Caribbean Series after a half-century-long estrangement. But a much heralded re-entry into the showcase tournament matching top squads from the Caribbean winter circuits (Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic) has brought only mixed results; Villa Clara was unceremoniously eliminated with only a single win in four contests in 2014 (in Venezuela) and Ciego de Avila suffered an identical fate two years later in Santo Domingo. Pinar did walk off with a Caribbean Series banner in San Juan during the intervening year, but only after also claiming but one victory in the opening round-robin before surging behind the slugging of Freddie Cepeda and Yulieski Gourriel in the pair of playoff contests. The Caribbean Series visits were also the unfortunate settings for several additional crucial ballplayer defections, including those of promising pitching prospect Vladimir Gutierrez in San Juan and star slugger Yulieski Gourriel in Santo Domingo.

Recent Cuban seasons have been marked by a number of memorable individual performances beyond Abreu’s near Triple Crown (losing only the RBI crown to Céspedes) in the Golden Anniversary 2011 season and Despaigne’s record-busting 36 homers a year later. Despite only one national team appearance, durable infielder Enrique Díaz retired with the 2012 disbanding of his Metros ballclub after a 26-year career run that left him as the all-time leader in base hits, runs scored, triples, and stolen bases. Wrapping up his Cuban career with a true bang, slugger Yulieski Gourriel amassed an unparalleled .500 batting average (49 games and 174 ABs) before abandoning the national squad in the Dominican Republic at the season’s two-thirds mark. After some controversy among league officials, it was at least tentatively decided to enter the lofty number in the league record books as Gourriel’s first official league batting crown.

Cuban League baseball has provided over a full half-century an isolated yet entertaining baseball universe unparalleled elsewhere in the sport. Both the big-league successes of a growing contingent of defectors and Cuba’s surprise victories in the World Baseball Classic have demonstrated an undeniable truth: that this league ranks alongside the Japanese pro leagues and perhaps just below the US majors among the trio of highest-level circuits. Cuba’s self-styled brand of “revolutionary baseball” today stands out for its experiment in truly regional competitions among strictly homegrown athletes. But the greatest legacy of this league in the end has to be its production of powerhouse national teams capable of dominating world tournament competitions for decades on end. For all its boasting points, however, the post-2010 Cuban league now seems to be living on borrowed time and struggling to keep anything of its earlier luster. Exploding player defections have killed league quality and gutted a once-proud national team system. Overtures by the Obama administration after December 2014 to end Cold War hostilities with Cuba have at first brought little in the way of détente between the Cuban Baseball Federation and an MLB brain trust still largely focused on Cuba as little more than a convenient plantation for harvesting future talent. And the Cubans’ efforts to relieve defection pressures on remaining top stars by allowing some to be loaned out to the Japanese circuit and the lesser Can-Am semipro league have done precious little if anything to stem the obvious domestic league disintegration.

Cuban National Series Championship Teams

| Year | Series | Team (Mgr) | W-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | #1 | Occidentales (Fermín Guerra) | 18-9, .667 |

| 1962-63 | #2 | Industriales (Ramón Carneado) | 16-14, .533 |

| 1963-64 | #3 | Industriales (Ramón Carneado) | 22-13, .629 |

| 1964-65 | #4 | Industriales (Ramón Carneado) | 25-14, .641 |

| 1965-66 | #5 | Industriales (Ramón Carneado) | 40-25, .615 |

| 1966-67 | #6 | Orientales (Roberto Ledo) | 36-29, .554 |

| 1967-68 | #7 | Habana (Juan Gómez) | 74-25, .748 |

| 1968-69 | #8 | Azucareros (Servio Borges) | 69-30, .697 |

| 1969-70 | #9 | Henequeneros (Miguel A. Domingüez) | 50-16, .758 |

| 1970-71 | #10 | Azucareros (Pedro P. Delgado) | 49-16, .754 |

| 1971-72 | #11 | Azucareros (Servio Borges) | 52-14, .788 |

| 1972-73 | #12 | Industriales (Pedro Chávez) | 53-25, .679 |

| 1973-74 | #13 | Habana (Jorge Trigoura) | 52-26, .667 |

| 1974-75 | #14 | Agricultores (Orlando Leroux) | 24-15, .615 |

| 1975-76 | #15 | Ganaderos (Carlos Gómez) | 29-9, .763 |

| 1976-77 | #16 | Citricultores (Juan Bregio) | 26-12, .684 |

| 1977-78 | #17 | Vegueros (José M. Piñeda) | 36-14, .720 |

| 1978-79 | #18 | Sancti Spíritus (Candido Andrade) | 39-12, .765 |

| 1979-80 | #19 | Santiago de Cuba (Manuel Miyar) | 35-16, .686 |

| 1980-81 | #20 | Vegueros (José M. Piñeda) | 36-15, .706 |

| 1981-82 | #21 | Vegueros (Jorge Fuentes) | 36-15, .706 |

| 1982-83 | #22 | Villa Clara (Eduardo Martin) | 41-8, .837 |

| 1983-84 | #23 | Citricultores (Tomás Soto) | 52-23, .693 |

| 1984-85 | #24 | Vegueros (Jorge Fuentes) | 57-18, .760 |

| 1985-86 | #25 | Industriales (Pedro Chávez) | 37-11, .771 |

| 1986-87 | #26 | Vegueros (Jorge Fuentes) | 34-13, .723 |

| 1987-88 | #27 | Vegueros (Jorge Fuentes) | 35-13, .729 |

| 1988-89 | #28 | Santiago de Cuba (Higinio Vélez) | 29-19, .604 |

| 1989-90 | #29 | Henequeneros (Gerardo Junco) | 37-11, .771 |

| 1990-91 | #30 | Henequeneros (Gerardo Junco) | 33-15, .688 |

| 1991-92 | #31 | Industriales (Jorge Trigoura) | 36-12, .750 |

| 1992-93 | #32 | Villa Clara (Pedro Jova) | 42-23, .646 |

| 1993-94 | #33 | Villa Clara (Pedro Jova) | 43-22, .662 |

| 1994-95 | #34 | Villa Clara (Pedro Jova) | 44-18, .710 |

| 1995-96 | #35 | Industriales (Pedro Medina) | 41-22, .651 |

| 1996-97 | #36 | Pinar del Río (Jorge Fuentes) | 50-15, .769 |

| 1997-98 | #37 | Pinar del Río (Alfonso Urquiola) | 56-34, .622 |

| 1998-99 | #38 | Santiago de Cuba (Higinio Vélez) | 46-44, .511 |

| 1999-00 | #39 | Santiago de Cuba (Higinio Vélez) | 62-28, .689 |

| 2000-01 | #40 | Santiago de Cuba (Higinio Vélez) | 55-35, .611 |

| 2001-02 | #41 | Holguín (Héctor Hernández) | 55-35, .611 |

| 2002-03 | #42 | Industriales (Rey Anglada) | 66-23, .742 |

| 2003-04 | #43 | Industriales (Rey Anglada) | 52-38, .578 |

| 2004-05 | #44 | Santiago de Cuba (Antonio Pacheco) | 55-35, .611 |

| 2005-06 | #45 | Industriales (Rey Anglada) | 56-34, .622 |

| 2006-07 | #46 | Santiago de Cuba (Antonio Pacheco) | 57-32, .640 |

| 2007-08 | #47 | Santiago de Cuba (Antonio Pacheco) | 61-29, .678 |

| 2008-09 | #48 | Habana Province (Esteban Lombillo) | 57-33, .633 |

| 2009-10 | #49 | Industriales (Germán Mesa) | 47-43, .522 |

| 2010-11 | #50 | Pinar del Río (Alfonso Urquiola) | 50-39, .562 |

| 2011-12 | #51 | Ciego de Avila (Roger Machado) | 54-42, .563 |

| 2012-13 | #52 | Villa Clara (Ramón More) | 50-37, .575 |

| 2013-14 | #53 | Pinar del Río (Alfonso Urquiola) | 52-35 .598 |

| 2014-15 | #54 | Ciego de Avila (Roger Machado) | 50-37 .575 |

| 2015-16 | #55 | Ciego de Avila (Roger Machado) | 54-32 .627 |

1962 to 1984-85, champion determined by cumulative record

1985-86 to 2011-12, era of postseason playoffs

2012-13 to present, era of split seasons

Cuban League Career Batting Leaguers (through 2015 season)

- Batting Average: Omar Linares, .368

- Home Runs: Orestes Kindelán, 487

- RBIs: Orestes Kindelán, 1,511

- Hits: Enrique Díaz, 2,378

- Runs Scored: Enrique Díaz, 1,638

- Steals: Enrique Díaz, 726

- Doubles: Rolando Meriño, 405

- Triples: Enrique Díaz, 99

- Slugging: Alfredo Despaigne*, .650

- Total Bases: Orestes Kindelán, 3,893

* Players still active in 2015

Cuban League Career Pitching Leaders (through 2015 season)

- Wins: Pedro Luis Lazo, 257

- Losses: Carlos Yanes, 242

- ERA: José Antonio Huelga, 1.50 (871.1 IP)

- Strikeouts: Rogelio García, 2,499

- Walks: Carlos Yanes, 1,310

- Saves: José Angel García*, 166

- Shutouts: Braudilio Vinent, 63

- Innings: Carlos Yanes, 3,836.1

- Games: Carlos Yanes, 714

- Relief Appearances: José Angel García*, 501

* Players still active in 2015

Sources

Alfonso López, Felix Julio. Con las bases llenas: Béisbol, historia y revolución (Havana: Editorial Cientifico-Técnica, 2008).

Bjarkman, Peter C. Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story (Lanham, Maryland, and London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016).

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007 and 2014). See Chapter 8: “Cuba’s Revolutionary Baseball (1962-2005),” and Chapter 7: “Havana as Amateur Baseball Capital of the World.”

_____. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005). See Chapter 1: Cuba: “Béisbol Paradiso.”

Cases, Edel; Jorge Alfonso, and Alberto Pentana. Viva y en juego (Havana: Editorial Científico Técnica, 1986).

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana – A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Guia Oficial de Béisbol Cubano. Havana: Editorial Deportes, various years (an Annual Cuban Baseball statistical guide published most years in the 1960s and 1970s and then regularly since 1998).

Rucker, Mark, and Peter C. Bjarkman. Smoke: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 1999).

Toledo Menéndez, Dagoberto Miguel. Béisbol Revolucionario Cubano, La Más Grande Hazaña – Aquino Abreu (Havana: Editorial Deportes, 2006).

Notes

1 The most extended and impassioned statement of this thesis is found in Roberto González Echevarría’s pioneering 1999 history of island baseball. González Echevarría unquestionably provides the most thorough and useful documentation of the Cuban sport’s 19th-century roots and also of developments across five decades of early 20th century professional winter league action in Havana. His account of baseball’s role in the 1880s and 1890s revolt against Spanish rule (and the early connections between the game and the emerging ideas of Cuban nationhood) are unparalleled. But González Echevarría’s insistence on placing the “Golden Age” of Cuban baseball in the 1940s and early 1950s (when fan interest was actually waning) and his regrettably brief dismissal of the talent levels in post-revolution play seem to reveal more political bias than painstaking historical research.

2 The saga of Cuban League escapees to major-league baseball is detailed in my recent book, Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story, which not only explores the impact of these stellar athletes on the big-league scene but also reveals the sordid human trafficking operations that have often been the unfortunate backstory to their arrival on the North American scene.

3 Due to a division of Habana Province into two distinct administrative entities during 2011, the league structure was slightly modified for the season beginning in winter 2011 (National Series #51). Two familiar teams (Havana’s cellar-dwelling Metros and the recently powerful Habana Province) were eliminated and replaced with teams representing the new political entities in Mayabeque (the Hurricanes) and Artemisa (the Hunters). The elimination of the Metropolitanos ballclub solved a longstanding league problem involving the unorthodox practice (discussed in the following note) of shifting players between Havana’s rival Industriales and Metropolitanos teams.

4 The system of single-team careers for all league players is not a hard-and-fast policy, although until most recently there were few exceptions to the general rule. The main exceptions have been the Metros and Industriales teams, both under control of the city’s INDER commissioners. A practice long persisted of employing Metros as an “unofficial” farm club where young talent could gain experience for a season or two before being elevated to the more celebrated Industriales roster. Many top Industriales stars of the 2000s (Alexander Malleta, Carlos Tabares, Rudy Reyes, Yadel Martí, and Frank Camilio Morejón among them) began careers with the capital city’s weaker club. Because of the sparse Isla de la Juventud provincial population, players are often moved to that club (as was the case with Havana-born future big leaguer Liván Hernández in the early 1990s) to strengthen an otherwise noncompetitive roster. Some players have also been moved by the league commission for developmental reasons, since the league mission is to train national team talent. One mid-2000s example is found with catcher Yenier Bello, who served a couple of seasons in Camagüey rather than sit on the bench in Sancti Spíritus behind veteran national team reserve Eriel Sánchez. There have also been rare cases where a player has been shifted simply to maintain postseason balance, such as in 1999 when all-star Matanzas outfielder Jorge Estrada was assigned to Pinar del Río for postseason games after Pinar was hampered by numerous late-season injuries. But all this would change in the fall of 2012 (National Series #52) when the league season was revamped into two separate rounds, the second 45-game segment containing only eight qualifying provincial squads staffed with supplemental reinforcements from eliminated teams.

5 The most detailed existing account of the Cuban League’s historical “opening day” of January 14, 1962 is found in Dagberto Toledo’s brief biography of double-no-hit hurler Aquino Abreu. Sketchier accounts are also found in the 1963 Official Cuban League Guidebook and in Alonso López’s Con las Bases Llenas volume.

6 The historical connections between baseball and Cuban national identity are not at all a late twentieth-century (post-Fidel) development, nor are the uses of the national sport as an instrument of foreign policy and Cuban image building. National pride was already being attached to Cuban victories at the earliest Amateur World Series events of the early 1940s. This conception of baseball as significant propaganda tool arises with the sport’s origins on the island and the significant early linkage between baseball and rebellion against Spanish overlords in the 1880s and 1890s. Discussions of Cuban baseball origins and the intimate link between the adopted national sport and Cuban national identity are provided in detail in both González Echevarría’s The Pride of Havana (Chapter 4: A Cuban Belle Epoque) and my own 2007/2014 McFarland volume (Chapter 5: Myths and Legends of the Cuban Professional League).

7 Recent remunerations for Cuban ballplayers are discussed in this volume’s biography of Omar Linares. INDER does not release any formal figures on salaries, but can be estimated that national-team stars until recently collected between 200 and 400 dollars (in equivalent Cuban currency) monthly, along with additional perks such as new automobiles and houses. Other league players make considerably less but do earn salaries commensurate with an average Cuban laborer. Some caustic 2006 World Baseball Classic (San Juan) postgame press conference comments by national team manager (and later league commissioner) Higinio Vélez reflect the Cuban take on the notion of baseball professionalism. When asked about his amateur players competing against pros, Vélez hastened to respond that his ballplayers were professional by any standard. “Our guys spend all their time training and playing and devote themselves to their profession which is ballplaying,” Vélez retorted to the attempts to brand his Cubans as unfortunate amateurs. He then disarmed the assembled press corps by inquiring: “In the United States do you claim that your schoolteachers are not professionals just because they do not make the same kind of salaries as top rock stars or all-star big leaguers?”

8 This feature was somewhat modified with the recent introduction of the split-season format which resulted in some top players being drafted onto different clubs (those that survived the qualifying round) for the second-stage championship round. Also increasingly in recent seasons, some players have been allowed to switch provincial residence – the most notable case being the transfer of the three Gourriel brothers (including star slugger Yulieski) from the Sancti Spiritus roster to the Havana Industriales team on the eve of the 2013-14 campaign.

9 Orestes Kindelán’s record 487 career home-run numbers, for example, are broken down as follows: 296 in 21 National Series (an unspecified number of which came in playoff matches), 165 in 13 Selective Series, 26 in two Revolutionary Cup tournaments. There is no available encyclopedia for Cuban League baseball that provides detailed composite career stats for league players on a season-by-season basis. Annual Cuban League guidebooks (published regularly since 1998) contain career totals only, with no individual season breakdowns. The best data on Cuban baseball is found on the BaseballdeCuba.com website launched by Ray Otero in 2005 and constantly expanded over recent seasons. Nonetheless, this website as of early 2016 provided only incomplete statistical data for players performing before the 2000 season. Baseball-Reference.com does provide individual player yearly totals, but only since the mid-’90s.

10 Detroit Tigers two-season washout Bárbaro Garbey flashed brief promise in the mid-’80s (1984-1985) and was seen as perhaps the long-awaited first Cuban slugger to arrive in North America with legitimate pro credentials. But Garbey fizzled quickly in the majors and instead became little more than the answer to an obscure trivia question about who was the first post-1962 Cuban League refugee to don a big-league uniform. The stocky outfielder had paced the Cuban circuit in RBIs in 1978, then was booted from the league with more than a dozen countrymen for reported involvement in a little-publicized game-fixing operation. The ex-Industriales mainstay was sent packing to US shores by the Cuban government along with other political undesirables during the Mariel “Freedom Flotilla” of spring 1980, soon signing on with the Detroit Tigers, who debuted him with Class-A Lakeland of the Florida State League. When news of Garbey’s Cuban antics reached the American press (in 1983 while he was still with the Tigers’ Triple-A team in Evansville) he suffered a brief second suspension from minor-league action which in the end was only an apparent “formal” slap on the wrist from Organized Baseball. After rapidly playing his way out of the majors (following brief trials with both Detroit and the Texas Rangers, marred by a number of disciplinary infractions), Garbey reappeared as a 37-year-old union-busting “replacement player” for Cincinnati during 1995’s lockout-year spring training.

11 In my Omar Linares biography I discuss in some detail the reasons offered by one particular island superstar for his own personal choice to remain loyal to the Cuban system and thus to reject the promises of huge financial rewards from the North American professional leagues. All Cuban ballplayers have their own truly individual and highly personal reasons for either staying or leaving, but one indisputable fact is that the huge majority long remained loyal to the island’s unique brand of baseball structure despite worsening Cuban economic conditions in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Most “defectors” before the early 2000s were second-tier athletes with little chance of earning the perks associated with national team status; a large majority were natives of the capital city, where athletes are perhaps more aware of their economic shortfall due to the larger number of their fellow citizens earning elevated salaries (as hotel and restaurant workers) in the extensive Havana tourist industry. Discussion of how and why the situation changes over the most recent half-dozen years (to 2016), plus full listing of Cuban baseball defectors (through late 2015) is provided in Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story.

12 There is some controversy surrounding the issue of the batting Triple Crown in Cuba. For five seasons in the late 1980s and early ’90s (National Series XXVII-XXXI) individual titles were awarded separately for the two divisions of the National Series. In 1988-1989 Kindelán did pace the Oriental Division in batting (.402), homers (24), and RBIs (58). Two decades later the Cuban baseball press continued to stress that there had never been a “true” Triple Crown champion, since Kindelán did not pace the entire league in all three categories (leading the Occidental Division leaders only in homers). But under the record-keeping traditions of the season in question, it can be claimed that Kindelán was a legitimate Triple Crown winner.