Babe Ruth’s Final Legacy to the Kids

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

“The only real game in the world is baseball. In this game, you have to come up from youth. You’ve got to start way down at the bottom, if you’re going to be successful like those fellows over there (the Yankees lining the field between home and first base).” – Babe Ruth, April 27, 1947, when being honored at Yankee Stadium.

Babe Ruth had taken ill, and throat surgery had kept him out of the public eye for three months. He was most touched by his welcome that day from 14-year-old American Legion ballplayer Larry Cutler, who said, “From all us kids, it’s swell to have you back.”1

During the 1940s Babe Ruth was involved in several national youth all-star games played in New York, and promoted youth baseball through his work with the American Legion. In 1944 Ruth hosted a radio program sponsored by the A.G. Spalding Sporting Goods Company, and on August 5 he hosted the several boys who were in town to play in the Esquire’s All-American Boys’ Baseball Game. Young Jim Enright of St. Louis asked the Babe how a player could learn to throw a ball harder and faster. Enright was just about the youngest player to participate in any of the games. He had turned 15 on July 21, 1944, making him 15 years and 17 days old on game day. Ruth replied, “Constant practice. Your arm won’t come up if you use it only once a week. You must practice hard every day. If you do, I’d say you will be able to throw the ball 20 feet further in a week.”2

Enright, a second baseman, never played professional baseball. Leonard Cohen of the New York Post told his readers that the young man, who had just completed his freshman year of high school, was also a soccer player and dreamed of studying journalism at Notre Dame.3 Joe Fromuth from Reading, Pennsylvania, asked the Babe if he could tell him a joke. Fromuth explained that players run faster from first to second than they do from second to third because there is a “short stop” between second and third. Ruth was amused.4

Before the game, held on August 7, Ruth was one of several dignitaries who addressed the crowd of 17,803 spectators. In the pregame festivities, he stepped to the microphone at home plate and said that it mattered little which team won the All-American contest so long as it was played cleanly and hard.5 Each of the 29 players who participated in the game received a baseball autographed by The Babe.

Ruth managed the East squad in the Esquire’s Game at the Polo Grounds on August 28, 1945. The West squad was managed by Ty Cobb. Future Philadelphia Phillies star Curt Simmons emulated Ruth in the game. After pitching the first four innings, allowing one earned run in the third inning when the West scored four times, he was removed from the mound on the short end of a 4-0 score. Simmons switched to the outfield for the final five innings. In the ninth inning, with one on, he hit the longest drive of the game. His triple to center field drove in a run, and he scored the tying run during a three-run rally as his East team came from behind to win, 5-4. Simmons was chosen the game’s MVP. Remembering his experience in New York, Simmons said, “He called everybody kid. But I remember he said, ‘Hey kid, you’re pitching.’ So I got a base hit when I was pitching, and after I pitched he said, ‘Go play right field.’ So I got to play the whole game, and I hit a triple toward the end of the game, and we ended up winning.”6

Future major leaguer Bob DiPietro remembered a scene during a pregame practice at the Polo Grounds on August 27, when Ruth was frustrated with one of his players in the batting cage. “He grabbed the bat from one of the players and told the kid, ‘Get the hell out of the batting cage. You aren’t worth shit as a hitter.’ He said, ‘Carl (Hubbell), groove a few of ’em here. Let me show them how to hit.’ Carl Hubbell was pitching! I look back. Cobb, Ruth, Hubbell, and what did I get? Zip (autographs)! Ruth hit six balls into the stands. It was the damnedest exhibition I’d seen. And he was in a sweat suit. But he had that great swing. Of course, the Polo Grounds, it was very short down both lines, but he hit a good drive to center field. He put on a show; it was great.”7

In 1946, sportswriter Max Kase of the New York Journal-American was instrumental in creating what came to be known as the Hearst Sandlot Classic. In that first year, it was known as the Hearst Diamond Pennant Series. The game featured a team of New York All-Stars against a team of US All-Stars. Early on, Kase enlisted the aid of Babe Ruth, who served as honorary chairman in 1947. Harry Schlacht of the Journal-American noted that Ruth “set the spark which kindled a flaming torch in the hearts of the kids of the nation.”8 The Babe himself stated that “The Hearst papers are doing a grand job in the sandlot program for the youngsters. It keeps the kids off the streets; It keeps them out of mischief; It builds them up physically; It helps them to become better citizens.”9

On November 26, 1946, Ruth entered French Hospital and over the next 21 months he would rage war against a cancer that would take its toll in the end.

“Fellows, I can’t say a lot. But boys, you know how I feel toward the kids. I love ’em and that’s why I went as far as I did. They didn’t swing the bat for me, but, well, they helped. I’m getting pretty old now, but I’m going to do all I can for them.” – Babe Ruth, April 8, 1947, when he was speaking with the media after accepting a position as a consultant with the American Legion baseball program.10

On April 27 a crowd of 58,339 fans filled Yankee Stadium for Babe Ruth Day, a day celebrated throughout baseball. The Sultan of Swat had undergone major surgery on his throat on January 6, 1947, and spent 82 days in the hospital. He was but a shell of his former self and barely spoke above a whisper. Nevertheless, during the summer of 1947, Ruth promoted youth baseball, working with the Ford Motor Company to support the American Legion Junior Baseball Tournament. He also took seriously his role as the honorary chairman of the 1947 Hearst Classic.

Members of the East All-Stars with manager Babe Ruth at the 1945 Esquire’s All-American Boys Baseball Game. Seated (and smiling) at Ruth’s left shoulder is Burt Stone. In front of Stone is Curtis Simmons from Egypt, Pennsylvania. (Courtesy of Stone’s daughter, Laurie Kandel)

“The game he graced so well was graced once more by Ruth as it passed another unforgettable milestone with the greatest sandlot game in history.” – Lewis Burton, New York Journal-American.11

The 1947 Hearst game was played on August 13. In terms of attendance (31,123 fans), future major leaguers (nine), and runs scored by a team (13 by the US All-Stars), the 1947 Hearst game was the best in the 20-year history of the event.

Of course, the icing on the cake at the 1947 game was the appearance by the game’s honorary chairman. Ruth took his seat during the bottom of the second inning of the game and received a standing ovation that stopped the game. He was late after accepting a series of engagements that would tire the healthiest of men. First, he visited the bedside of a sick youngster in New Jersey. Then, before heading to the Polo Grounds, he stopped by New York’s amateur boxing finals where he signed more than a few autographs.12 The Babe was interviewed during the slugfest by Jack Conway of the Boston Daily Record. Ruth proved himself quite the prognosticator when he said, “I would not hesitate to predict that a least a half-dozen of the 23 boys on the United States All-Stars will be in major league baseball within three or four years.”13

Ruth was still quite ill with throat cancer and was barely audible, but he asked to speak with the game’s MVP. That was Don Ferrarese who had traveled to the game from Oakland, California. Ferrarese was one of the seven US All-Star players to make it to the big leagues. He was on the mound and paused when Ruth arrived in the second inning. One person did not know what all the fuss was about. Pitcher Hy Cohen of the Journal-American All-Stars related a couple of memories from that night. Before the Hearst game, Babe Didrikson, the famous female athlete, borrowed Cohen’s glove when she gave her pregame exhibition. Cohen’s father, who did not know much about baseball, was at the game and seated next to Babe Ruth. He didn’t recognize The Bambino.

Ruth was able to travel to spring training in 1948, At a game on March 18, he told Arthur Daley of the New York Times that he hoped to be playing golf that summer. Daley wrote:

“Seeing him again, you realize anew the tremendous magnetism of the man and the unshakeable hold he has on public esteem. There never was another like him and there never will be. The fans leap to their collective feet and cheer frenziedly (as they did on August 13, 1947) whenever he enters a ballpark. Small boys, whom the Babe always loved, stare adoringly at him.”14

Ruth returned from Florida having gained a few much-needed pounds and was planning to depart for California at the end of April to assist in the filming of his biopic, The Babe Ruth Story. Before he left for the Coast, his autobiography, written with Bob Considine, was released. These words from the first paragraph convey The Babe’s never-ending love affair with the young boys who were his adoring fans:

“I was a bad kid. I say that without pride but with a feeling that it is better to say it. Because I live with one great hope in mind: to help kids who now stand where I stood as a boy. If what I have to say here helps even one of them avoid some of my own mistakes, or take heart from such triumphs as I have had, this book will serve its purpose.”15

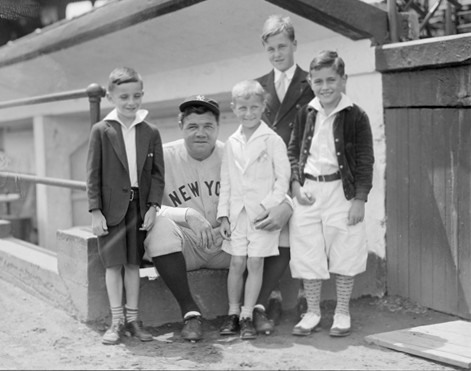

New York Yankee Babe Ruth with four young boys alongside the third base dugout at Fenway Park, ca. 1931-34. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

On June 5 Ruth traveled to Yale University, where he presented the manuscript of his book to George H. W. Bush, the Elis’ captain and first baseman, and the future president.16 And on June 13 he returned to Yankee Stadium for Old-Timers Day. He donned his old uniform as his number 3 was officially retired at a ceremony marking the 25th anniversary of Yankee Stadium. A week later The Babe joined with Dizzy Dean in St. Louis at a youth baseball clinic before a Browns-Yankees game at Sportsman’s Park. But on June 24, Ruth re-entered the hospital.

He emerged briefly on two occasions. On July 13 he traveled to Baltimore, his childhood home, for the annual interfaith charity game, which featured International League rivals Baltimore and Jersey City. When rain caused the festivities to be postponed to the following night, The Babe returned to New York. He was too ill to stay the night. The last time he appeared in public was when he attended the film premiere of his life story on July 26. By then, he was gravely ill.

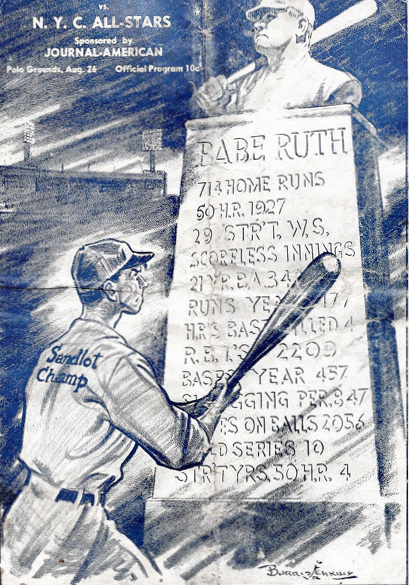

Baseball lost Babe Ruth on August 16, 1948. He was buried three days later, and the 1948 Hearst game on August 26 was played in his memory. Just before his death, one of the New York area newspapers featured a drawing of The Babe cheering the kids on from his hospital bed. The picture was titled “Your Cheering Section Kid.” Joe DiMaggio stepped in as honorary chairman, and each of the players received an autograph from the Yankee Clipper. During the pregame festivities, DiMaggio said, “Babe Ruth was my inspiration. It is one of my great regrets that I came too late to play alongside The Babe.” Dick Groat’s one vivid memory of his games in New York was standing more than an hour outside in the rain, across from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, during Ruth’s funeral on August 19, hoping, along with his roommate, Art Ruffing of Pittsburgh, to get a glimpse of Ruth’s funeral procession.

Before the game, columnist Bill Corum served as the master of ceremonies and introduced the participants in the Memorial to Babe Ruth. One tribute featured Al Schacht doing his pantomime of The Babe’s called shot in the third game of the 1932 World Series, while Robert Merrill brought tears to everyone’s eyes with his rendition of “My Buddy.”17 The tributes were many. On hand was New York businessman Johnny Sylvester, who was 11 years old when The Babe made his fabled hospital visit in St. Louis in 1926, promising to hit a home run in the next game of the 1926 World Series – a visit that sportswriters of the day claimed to have saved the young man’s life.18 The Police Athletic League choir sang “Auld Lang Syne” and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” The St. Vincent’s Drum and Bugle Corps from Bayonne, New Jersey, also performed.

Also participating in the pregame festivities were Metropolitan Opera soprano Annamarie Dickey, who sang the National Anthem, National League President Ford Frick, who had chronicled Ruth when he was with the Journal-American, and comedian Joe E. Brown.19

The 1949 Hearst Classic was held two days after the anniversary of Ruth’s death. DiMaggio read a message to youngsters as Ruth was remembered.

To the end, The Babe was devoted to his young fans, and on his deathbed made provision in his will that 10 percent of this estate was bequeathed “to the interests of the kids of America.”20

ALAN COHEN serves as Vice President-Treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter and is a datacaster for the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Rockies. His biographies, game stories and essays have appeared in more than 60 SABR publications. His work on youth ballgames awakened an interest in the role of Babe Ruth in these games. Alan has continued to expand his research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946- 1965), which launched the careers of 87 major-league players, and had Babe Ruth as its honorary chairman in 1947. He has four children, nine grandchildren, and one great-grandchild and resides in Connecticut with wife Frances, their cats Ava and Zoe, and their dog Buddy.

Sources

In addition to sources shown in the notes, the author consulted:

Schumach, Murray. “Babe Ruth, Baseball Idol, Dies at 53 after Lingering Illness,” New York Times, August 17, 1948: 1.

The author interviewed Don Ferrarese, Billy Harrell, Rudy Regalado, Dick Groat, and Hy Cohen, each of whom played in the 1947 Hearst Sandlot Classic.

Notes

1 “Babe Ruth Receives Tributes on Return to Yankee Stadium,” Baltimore Sun, April 28, 1947: 17.

2The Sporting News, August 10, 1944: 13.

3 Leonard Cohen, New York Post, August 5, 1944: 18.

4 Richard Flannery, Reading Eagle, October 18, 1998: D-2.

5 Louis Effrat, New York Times, August 8, 1944: 12.

6 Richard Panchyk. Baseball History for Kids: America at Bat from 1900 to Today, with 19 Activities (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2016), 53.

7 Nick Diunte, “Bob DiPietro” SABR BioProject.

8 Harry H. Schlacht,” The Hearst Sandlot Classic – A Living Memorial to Babe Ruth,” New York Journal American, August 26, 1948 (reprinted in the Milwaukee Sentinel, August 26, 1948: 14).

9 Harry Schlacht, “The Spirit of Babe Ruth Lives On,” New York Journal-American, August 16, 1949: 16.

10 Oscar Fraley, “Broken in Health, Babe Ruth Will Aid Legion Baseball,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, April 9, 1947: 8.

11 Lewis Burton, “Record Crowd Sees U.S. Sandlotters Win,” New York Journal-American, August 14, 1947: 24.

12 Edgar C. Greene, “Babe Still ‘Do as I Please’ Guy,’” Chicago Herald-American, August 14, 1947: 24.

13 Jack Conway Jr., “Sandlotters Back; Hail Keany Clout,” Boston Daily Record, August 15, 1947: 40.

14 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Mostly About Babe Ruth,” New York Times, March 19, 1948: 30.

15 Babe Ruth (as told to Bob Considine), The Babe Ruth Story (New York: Pocket Books [E.P. Dutton], 1948), 1.

16 John Rendel, “Ruth Gives ‘Story’ to Yale Library: Babe Presents His Manuscript Before Game in Which Elis Beat Princeton, 14-2,” New York Times, June 6, 1948: S-1.

17 Tommy Kouzmanoff, Milwaukee Sentinel, August 27, 1948: part 2, 3.

18 Al Jonas, “U.S. Aces in Drill: 35,000 Expected at Sandlot Classic,” New York Journal-American, August 22, 1948: L27.

19 Charlie Poeckel, Babe and the Kid: The Legendary Story of Babe Ruth and Johnny Sylvester (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007), 132.

20 “Babe Left ‘Kids’ Share in Estate,” New York Journal-American, August 23, 1948: 1.