Babe Ruth’s National League ‘Career’: 28 Games with the 1935 Boston Braves

This article was written by Saul Wisnia

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

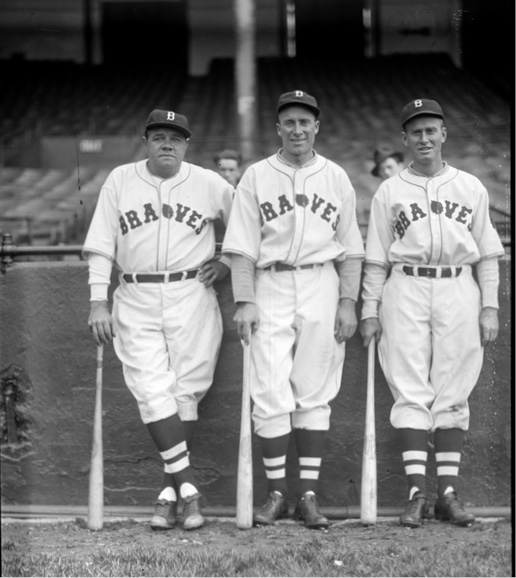

Babe Ruth, left, poses with Boston Braves teammates Wally Berger and Hal Lee in 1935. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

The buildup had been tremendous, and for a few days, at least, the hype seemed completely justified.

On April 16, 1935, the Boston Braves hosted the New York Giants in their home opener at Braves Field. The contest featured a matchup of two of the National League’s leading power hitters in Boston’s Wally Berger and New York’s Mel Ott, but all the pregame buzz was about the Braves left fielder batting in front of Berger and making his NL regular-season debut: Babe Ruth.

Ever since the Braves owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, announced the signing of the all-time home-run king in late February, Boston’s many daily newspapers had been crammed with stories speculating whether Ruth could help the city’s NL franchise improve upon the previous year’s fourth-place finish. Even though he had slipped from 41 homers to 34 to 22 in his last three seasons with the Yankees, and hit an un-Ruthian .288 with 84 RBIs in 1934, Fuchs and Braves fans hoped that the Bambino might find a new burst of productivity in the city where his big-league career began as a Red Sox pitcher 20 years earlier.1 Skeptics pointed to his declining numbers and advancing age – Ruth had turned 40 on February 6 – as reasons to doubt such optimism.2

A few days before the opener, the new recruit vowed to make a good showing for Braves manager Bill McKechnie’s club. “Wait till that bell rings,” Ruth told reporters. “That’s when I shall put the pressure on myself, and believe me, I know I am going to play a lot better ball than a whole lot of people think. I am not bothered about the hitting. I know when my eye is getting right – and it’s just about right now. My legs won’t be so bad.”3

The bell rang on April 16, and Ruth was indeed ready. In the first inning, stepping to the plate with Billy Urbanski on second base and one out, he lined the second pitch from Giants ace Carl Hubbell into right field for a run-scoring single and a 1-0 Boston lead. This quickly grew to 2-0 when Buck Jordan singled to bring The Babe home.

It was still 2-0 in the fifth with Urbanski on second again when Ruth launched a 2-and-2 screwball from Hubbell “20 feet up” into the right-field stands behind Ott, who shrugged his shoulders as it left the big ballpark. The fans cheered wildly again, and McKechnie – who had (justifiable) concerns about Ruth’s unexplained contractual role as his “assistant manager” – was caught up in the moment enough to step away from his third-base spot coaching box and grasp the Babe’s hand as he passed by on his 709th career regular-season home-run trot (and 16th against NL competition, including World Series play).4 Always knowing how to play to the crowd, Ruth doffed his cap after crossing the plate.5

Hubbell, who had counted Ruth among his record five straight strikeout victims at the previous July’s All-Star Game, was haunted by The Babe in more ways than one on this day. In the fifth inning, Hubbell blooped a pitch from Braves pitcher Ed Brandt over third base for what appeared to be a run-scoring single, only to see Ruth come sprinting in from left field to grab the ball with his outstretched glove near the foul line. He then continued running right into the Boston dugout to the delight of an estimated 25,000 chilly fans who included many state and city workers given a half-holiday so they could attend that game.6

The final score was 4-2, with Ruth playing a part in all four Boston runs and making the defensive play of the afternoon. His glove work was perhaps the biggest surprise, as newspaper reports from spring training had been filled with accounts of Ruth’s struggles in the field. There was even a Johnny Sylvester-like story attached to the game; 14-year-old Bobby Baker, who had “been critically ill all spring,” received a baseball autographed by Ruth at his Salem Hospital bedside the day of the opener. Upon hearing of his hero’s home run, nurses said, “Bobby’s spirits soared” and he vowed to get well.7

Fittingly, given Ruth’s love of children, a youngster also wound up with the home-run ball. Sergeant Michael Carr of the North End Police Station was working a detail at the game and caught the shot on a bounce in center field. Carr turned down $25 from a fan for the ball, and when he got home, he gave it to his 9-year-old son, George. The other George, Ruth, had autographed it.8

Bill Carrigan, who managed the Red Sox with and against Ruth in earlier years, said that “Babe never hit the ball any harder during the height of his career than he did today.”9 Ruth himself was understandably upbeat; the day after the game, he sat smoking black cigars and told Jimmy Powers of the New York Daily News, “Listen, kid, you can tell the world poppa (meaning himself) is happy. I said I might hit forty home runs this summer, didn’t I? Well, change that. If I’m lucky I’ll hit fifty.”10

Homer number two came on Easter Sunday, April 21, against the Dodgers. It gave Ruth a .400 batting average for the young season, but he had already struck out six times in 15 at-bats – high by even his free-swinging standards. Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel, convinced that Ruth was still a force, noted, “I played against the Babe in World Series games when he was at his best. He missed quite a few those days and he still does today. But the old Babe was always dangerous with a bat in his hand and he always will be as long as he can walk up to the plate.”11

Stengel’s prediction did not come to pass. When the Braves hit the road, Ruth went 0-for-10 in four games at New York and Brooklyn with four more strikeouts. His average of more than one walk per game in the early going showed the respect pitchers still had for Ruth, but word spread that the Babe’s mighty bat now had holes. Hurlers began offering him a steady stream of curveballs, with almost universal success.

Defensively, Ruth’s shortcomings were also becoming acute. In a 6-5 loss at the Polo Grounds on April 23, he misjudged a pop fly by Bill Terry in the third inning that fell behind him for an inside-the-park home run, and one inning later booted Gus Mancuso’s single into a double.12 At home vs. the Phillies on April 29, he guessed wrong on a line drive with the bases loaded, resulting in three runs scoring.13 The Braves managed to win that game, 7-5, but this was becoming the exception rather than the rule. By early May, Boston had fallen into seventh place, ahead of only lowly Philadelphia, and matching the previous year’s 78-73 record seemed less likely by the week for McKechnie.

Boston Braves baserunner Babe Ruth steps on home plate behind Brooklyn Dodgers catcher Al Lopez as Braves teammate Wally Berger (#4) and home plate umpire Dolly Stark look on at Braves Field. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library)

Along with wins on the field, Braves boss Fuchs had hoped that Ruth could bring in big attendance figures at the gate. This was the case on May 5, when 31,200 fans jammed Braves Field to see Boston battle the reigning NL champion Cardinals – with the added attraction of the first-ever matchup between young pitching whiz Dizzy Dean and Ruth. It was strictly a one-sided affair; not only did Babe go hitless with a strikeout in a 7-0 loss, but Dean even beat the Bambino at his own game by hitting a home run and single. The next day, against Pittsburgh, just 2,000 fans showed up as Babe sat things out with a bad head cold.

Rumors were already spreading about Ruth’s possible future with the Braves. On April 25 an unattributed story appeared in the Boston Globe in which Fuchs denied reports printed in New York papers that Ruth would be succeeding McKechnie as Boston manager within two weeks. “There’s absolutely nothing to that story,” Fuchs said. “Save for the change of date, it’s the same story I’ve been hearing since Ruth came to the Braves. There was never any truth to it and there’s none now.”14

Whatever the Babe had on his mind, it wasn’t helping his game. By May 12 he had gone 10 straight games and 20 at-bats without a hit – dropping his average to .171.15 He had also missed several contests due to his cold and a sore knee. The rumors of discord between Ruth and McKechnie persisted. Fuchs did his best to deflect them, stating that he hoped both men would “remain with the Boston Braves as long as they live.” The owner also showed no public concern over Ruth’s slump, stating that “It is my belief … that as soon as the weather conditions are normal, and the physical condition, caused by a cold throughout his system, is improved, he will disprove the prediction of some of the New York writers – that his ability and power in baseball is a thing of the past.”16

Despite Fuchs’s comments, Ruth was losing his enthusiasm as his average and the team’s fortunes continued to slide. Still, his loyalty to his fans and his pride won out. “The Babe has intimated several times within the last two weeks that he has felt like quitting the active game,” the Boston Herald reported in mid-May. “But he said yesterday he would stick it out and give it all he had to further the best interests of the team and of Judge Fuchs.” A long road trip loomed for the Braves, with several cities planning “Babe Ruth Day” events that would mean big crowds and a chance for Fuchs to keep the struggling club afloat financially.17

Ruth broke a 26-day hitless skein in the opening game of the trip on May 17 at St. Louis, going 1-for-4 with a single. After this game, he denied more rumors – this time reports that he would quit after the road trip. “I’m going to play here tomorrow and keep right on playing as long as I have anything left,” he told reporters. “I have a cold but am feeling better and am in good shape.”18

On May 21 at Chicago, Ruth had his first home run in exactly a month. From there the Braves moved on to Pittsburgh, where in the next two games he was an uninspiring 1-for-8 with a single. His average was now down to .153, and perhaps it was a measure of manager McKechnie’s lack of talent that he continued to bat him third in the order. The assistant manager likely had no say in the decision; like the “vice president” title also in his contract, it was clear by now that both designations meant nothing.

There was also no sign that Ruth, or the Braves, would ever emerge from their respective slumps. Boston entered play on Saturday, May 25, in last place with an 8-19 record; after a 2-5 start to their trip, they still had seven more games to go before heading home. They were facing a Pittsburgh team that was eyeing a three-game sweep and would stay in the pennant hunt well into September. Against this uninspiring backdrop, and with all but the most optimistic fans already writing his epitaph, Babe Ruth broke through with his best game since Opening Day – and one of the most awesome displays of pure power in his career.

In the first inning, with one out and Urbanski on second, Ruth faced Pirates right-hander Red Lucas and homered into the right-field stands. In the third, again with one out and one on, he launched a Guy Bush pitch to right, this time an estimated 450 feet into the upper deck. The Braves now led 4-0, but The Babe’s big day was far from over. After Pittsburgh came back with four runs in the fourth inning to tie it, Ruth faced Bush again in the fifth and singled in Les Mallon (who had also scored on his second homer). Boston was back in front, 5-4; more precisely, it was Ruth 5, Pittsburgh 4.

Babe’s teammates gave up the lead once more, and it was 7-5, Pittsburgh, when he came up for the fourth time in the seventh inning. Bush was still in the game and delivered a fastball to Ruth between the knees and waist. As writer Leigh Montville would describe it, Ruth hit the ball “straight into the air, high, like a pop-up, except it kept carrying, far, far, over the right center-field fence at Forbes Field, bounced in the middle of the street, and rolled into Schenley Park. The estimated distance the ball traveled was well over 500 feet, the longest home run ever hit at Forbes Field.”19

It was Ruth’s fourth hit, third homer, and sixth RBI of the day. The afternoon sent the Babe’s average shooting up to .206, but amazingly the Braves still lost, 11-7 – another setback in a last-place season that would eventually bottom out with one of the worst marks (38-115) in major-league history.

Montville and other biographers claim that Ruth’s wife, Claire, and friends pleaded with him to quit after this game. It certainly would have been a Hollywood ending, and Hollywood apparently took note. In The Babe, a 1992 film that barely outshines the dreadful Babe Ruth Story, released in 1948, the title character (played by John Goodman) actually does quit after his three-homer day in Pittsburgh in a fictionalized fit of passion that allows Ruth to finish his career and the film on a high note. He realizes he is never going to manage the Braves, and that his best days are behind him, so he literally walks away. The reality was far less dramatic. Knowing that several more National League cities planned to honor him in the weeks ahead and committed to satisfying his fans and fulfilling his contract, Ruth stayed with the club.

His brilliance, however, abandoned him as fast as it had returned. After hitting homers 712, 713, and 714 of his career on May 25, he never had another hit of any kind. He struck out three times in four at-bats the next afternoon – Babe Ruth Day in Cincinnati – and his average dropped below .200 for the final time. He then went 0-for-5 over four contests, although he did manage to walk four times and score twice.

How far had Ruth fallen? In a scene so cruel it almost seems unfathomable, his near-immobility was the subject of scorn in Boston’s May 28 game at Cincinnati. Montville describes it: “In the fifth inning, the Reds attacked him in left field. Every batter purposely hit the ball to left in a five-run inning. Ruth, unable to move, was helpless as he tried to field the balls. When the inning ending, he went directly toward the clubhouse, not the dugout, as the fans jeered him.”20

Thankfully, the worst was over. On May 30, 1935, at Philadelphia, Ruth came up third in the first inning and grounded a Jim Bivin pitch weakly to Dolph Camilli at first base. Then, in the bottom of the first, Ruth removed himself from the game after falling in the outfield and reinjuring his knee. There was no clear indication to the estimated 18,000 fans at the Baker Bowl that they were witnessing history, but for the rest of their lives they could lay claim to seeing George Herman Ruth appear in his final major-league game.21

A few days later, the news made bold but differing headlines across the country. The New York Times perhaps got it best on June 3: “Babe Ruth ‘Quits’ Braves and Is Dropped by Club.” Ruth, sidelined by his bum knee, had been frustrated when Fuchs refused to let him skip a game he wasn’t going to play in anyway and attend a party with his wife aboard the ocean liner Normandie. So Ruth quit, was fired by Fuchs, and released by the Boston team, all in one dismal afternoon.

“I do not have to put up with this sort of treatment,” the .181 hitter told reporters, “and I will not return to the Braves as long as Fuchs remains in control of the club.”22

Ruth then got into his car for the drive from Boston back to New York. Fuchs sold the team a few months later, but the Babe never returned – to the Braves or any major-league club as a player. His Hall of Fame career was over, with final batting statistics that would be memorized by generations of fans: .342 average, 714 home runs, .690 slugging percentage, 2,214 RBIs, 2,174 runs scored.

It ended sadly, but no player’s time in the game was ever more glorious.

SAUL WISNIA has authored, coauthored, or contributed to numerous books on Boston and general baseball history, including Fenway Park: The Centennial, Miracle at Fenway: The Inside Story of the Boston Red Sox 2004 Championship Season, and Son of Havana: A Baseball Journey from Cuba to the Big Leagues and Back (with Luis Tiant). He is a former sports and news correspondent for The Washington Post and feature writer for The Boston Herald whose essays have appeared in Sports Illustrated, Boston Globe, Boston Magazine, and Red Sox Magazine. For the past 20 years, he has chronicled the special relationship between the Red Sox and young cancer patients as senior publications editor-writer at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Wisnia lives in his native Newton, Massachusetts, 5.7 miles from Fenway Park.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com for box-score, player, team, and season information as well as pitching and batting game logs, and other pertinent material.

Notes

1 Fuchs was also excited about the potential crowds that Ruth would draw. An estimated 48,000 fans had jammed Fenway Park for a doubleheader between the Yankees and Red Sox the previous August, widely speculated to be Babe’s last games in Boston as an active player. Since the ballpark had fewer than 35,000 seats, thousands of fans stood on the field in a roped-off area behind the center-field flagpole.

2 Ruth had just found out he was a year younger than he always thought; according to many sources, including The Big Bam, by Leigh Montville, the Babe believed he was born on August 6, 1894, until he saw his birth certificate while preparing for an October 1934 trip to Japan. His actual birth date was August 6, 1895.

3 Melvin Webb Jr., “Nothing Wrong with His Wrist, Cronin Assures Globe Writer,” Boston Globe, April 12, 1935: 27.

4 Interestingly, James Dawson’s game story in the New York Times stated that it was the 724th home run of Ruth’s career without noting that this number combined regular and postseason blasts. Dawson did not hold back his enthusiasm for the day’s star, writing that “Ruth was king again with the bludgeoning ash that brought him fame.” James Dawson, “Ruth’s Home Run Defeats Giants in Boston, 4-2,” New York Times, April 17, 1935: 29.

5 According to Arthur Siegel’s April 17 story in the Boston Herald, Ruth also declared the home run as a sixth-anniversary gift to his wife, one day early. “That’s one for the old lady,” he said after the shot. Arthur Siegel, “ “‘That’s One for the Old Lady,’ Says Babe; Rescues Vice-Presidents from Oblivion,” Boston Herald, April 17, 1935: 28.

6 While the April 16, 1935, attendance was widely noted in Boston newspapers as the largest Opening Day crowd in Braves Field history to that point, it was far below the 40,000 to 50,000 fans that the Boston Globe, New York Times, and other papers predicted would attend. The subpar weather liked played a big part. The half-holiday for city and state workers was mentioned in the Boston Herald’s pregame story by Burt Whitman, and governors from five of the six New England states were also in attendance. April 16 was also declared “Judge Emil Fuchs Day” in Boston, with the Braves owner given a bronze plaque by Massachusetts Governor James Curley that was later displayed at the ballpark permanently. Next-day newspapers at the time reported “nearly 22,000” (Boston Globe), or 25,000 (both the New York Times and New York Daily News).

7 “Curley to ‘Babe’ to Bobby Erases Sick Boy’s Gloom,” Boston Globe, April 17, 1935: 10.

8 “Boy Has First Home Run Ball Babe Hit in League as Brave,” Boston Globe, April 19, 1935: 15.

9 Hy Hurwitz, “Bill Carrigan Declares He Never Hit Ball Harder – Crowd Pays Fitting Tribute,” Boston Globe, April 17, 1935: 28.

10 Jimmy Powers, “Babe Revises H.R. Schedule! He Now Plans to Hit 50!” New York Daily News, April 17, 1935: 363.

11 Hy Hurwitz, “Babe No Pushover, Says Casey Stengel,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1935: 9.

12 Arthur Siegel, “Ruth Hailed by 47,000 in New York as Braves Bow to Giants, 6-5, in 11th,” Boston Herald, April 24, 1935: 1.

13 James O’Leary, “Braves Beat Phils 7-5, Wilson Injured,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1935: 20.

14 “Fuchs Denies Ruth Report,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1935: 25.

15 Ruth’s official totals for the hitless stretch, as tallied by the Boston Globe on May 13, 1935: 30 plate appearances, 11 walks, 9 strikeouts, 10 balls put in play for outs.

16 “Deny Dissention in Braves Ranks,” Boston Globe, May 8, 1935: 22.

17 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Gives Braves Squad Fight Talk,” Boston Herald, May 15, 1935: 14.

18 Associated Press, “Angry Bambino Denies He Will Quit Playing,” May 16, 1935. Appeared in New York Daily News, May 17, 1935: 81.

19 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 342.

20 Montville, 342-343.

21 In the last 18 games of Ruth’s major-league career, the Braves went 3-15. Taking out his 4-for-4, three-homer day at Pittsburgh, he was 3-for-43 in the other 17 contests.

22 Burt Whitman, “Slugger’s Plan to Attend Banquet in N.Y. Tonight Led to Break,” Boston Herald, June 3, 1935: 1.