Baltimore’s Forgotten Dynasty: The 1919-25 Baltimore Orioles of the International League

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

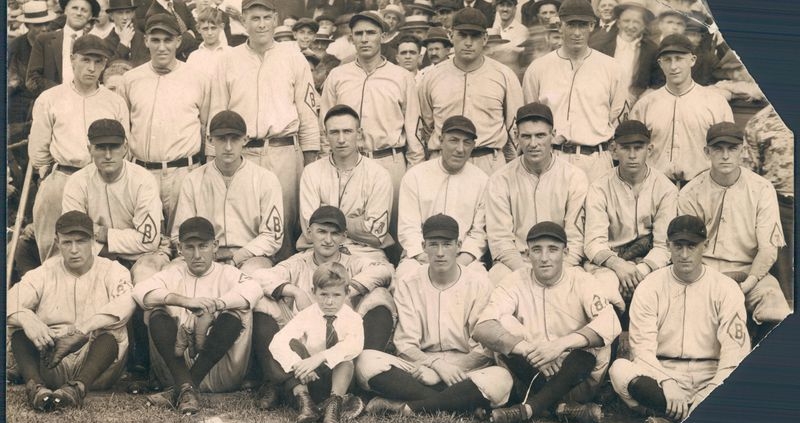

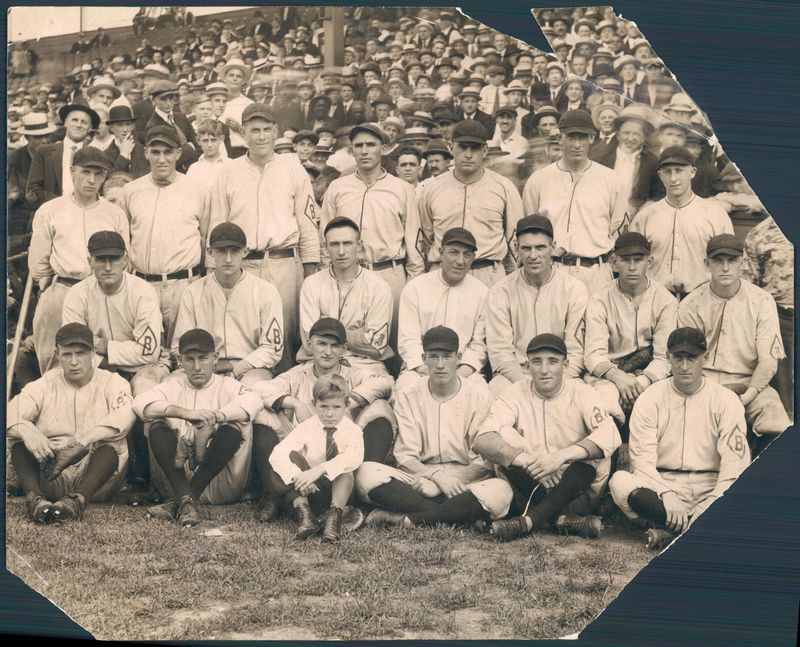

1920 Baltimore Orioles, International League champions. (BALTIMORE SUN)

1920 Baltimore Orioles, International League champions. (BALTIMORE SUN)

In 1920, the Baltimore Orioles were champions of the International League (IL) for the second straight year. Baltimore would win seven consecutive pennants (1919–25), and six of the championship teams are ranked in the top 20 of the 100 best minor league teams of the twentieth century by Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright.1 (See sidebar 1 below.)

Owner Jack Dunn had survived the invasion of the Federal League by selling off some of his players and hightailing it to Richmond, VA, then returning to Baltimore in 1916. He would create a minor-league dynasty, locking up his best players for years during a time when the IL was exempt from the major league draft. The man who had sold Babe Ruth to the Red Sox for a bargain price had learned his lesson, placing high price tags on players desired by big-league clubs. Dunn and 11 of his players are in the International League Hall of Fame. Only one player from the dynasty years made it to Cooperstown, and there should have been more. (See sidebar 2). This article will discuss these eleven players and the championship seasons of which they were a part.

Jack Bentley joined the Washington Nationals (nicknamed the Senators) at the end of 1913 and, in parts of four seasons, compiled a 6–9 record in 39 games as a pitcher. He was dispatched to Minneapolis of the American Association and, on August 18, 1916, was sent to Baltimore for the balance of the season. He was formally traded by Washington to Baltimore in early 1917 and was the cornerstone as Dunn rebuilt the Orioles.

Obtained by Dunn along with Bentley was Turner Barber, who was dealt to the Cubs in exchange for outfielder Merwin Jacobson, who starred with Baltimore from 1919 through 1924. Although his services had been secured prior to the 1918 season, Jacobson spent that year in Washington, DC, doing war-related work.

Bentley also came into his own as a hitter in 1916, and in 1917, batting .343. Suffering from arm trouble, he only appeared in one game as a pitcher. Baltimore improved to 88-61, finishing in third place, 2.5 games behind the league leaders.

Baltimore almost lost Bentley after the 1917 season. He was drafted by the Red Sox but entered the Army, serving with distinction in World War I. As 1919 began, he was still in France, and the Red Sox still had the rights to his services. Boston didn’t need Bentley at first base, as they had Stuffy McInnis. As Boston owner Harry Frazee hadn’t paid the $2,500 draft price for Bentley by February 1, Bentley returned to Baltimore.

In the abbreviated 1918 season, Baltimore continued to build. Otis Lawry, who had been obtained from the Athletics in a seven-player deal after the 1917 season, came into his own, batting .317. He played with the Orioles until midway through the 1924 season.

Eighteen-year-old Max Bishop was installed at third base in 1918. With Bentley still in Europe at the start of the 1919 season, Bishop played first base. His average through the season’s first eight games stood at .652 with seven extra-base hits.. Once Bentley returned, Bishop was moved to second base, and it was at that position that he would remain for the balance of his professional career.

New faces were on the left side of the infield in 1919. The shortstop was Joe Boley, who played in the low minors in 1916 and 1917 and did not play in organized baseball in 1918. He had taken a job at a plant with work related to the war effort in 1917, and he played on the plant’s semi-pro team in 1917 and 1918. One of his teammates in 1917 had been Bishop. Bishop suggested that Dunn sign Boley and the shortstop joined the Orioles in 1919.2

Fritz Maisel was popular with Baltimore when he played with them from 1911 through mid-1913. He was traded to the Yankees and was with them through 1917. He spent 1918 with the St. Louis Browns. His acquisition by Dunn as the team’s third baseman put another stone in place.3

Baltimore opened at home against Rochester on April 30, 1919, with Rube Parnham pitching. The 25-year-old had gone 38-19 with Baltimore over the prior two seasons, but until January 16, 1918, was property of the Philadelphia Athletics. He had appeared briefly, in a total of six games, with Philadelphia in 1916 and 1917. Parnham was Baltimore’s top pitcher in 1919, going 28-12.

Bentley returned to Baltimore on June 21, 1919. On his first day in the lineup, he started the second game of a doubleheader against Rochester and went 3-for-5 with a sixth-inning homer.4

Baltimore won the IL pennant by eight games. After the season, Baltimore did not participate in the Junior World Series, which was contested that year between the champions of the American Association and the Pacific Coast League.

Late in 1919, Dunn ensured the future success of the team by signing his stars to two-year contracts. He demanded top money for his players, including a man who came on board during the 1920 season: Robert Moses “Lefty” Grove. Only 20 years old, Grove got his professional start in 1920 with Martinsburg, West Virginia in the Class D Blue Ridge League. His 1.68 ERA and 60 strikeouts in 59 innings aroused the interest of Dunn, who secured Grove’s services.

Grove joined Baltimore in late June and won his first two outings. In his first appearance, on July 1, he defeated Jersey City 9-3 in the second game of a doubleheader giving the Orioles a one and a half game lead in the league standings. He allowed five hits in the abbreviated seven-inning contest. Three days later, he defeated Reading, 8-1. He scattered seven hits, struck out eight, and, in the fourth inning, struck out the side.5

Another new arm in 1920 was that of Jack Ogden. Ogden was obtained from Rochester, where he had gone 10-13 in 1919. With Baltimore, he shined, and Dunn held on to him through 1927. In six of eight seasons, he won more than 20 games, and his record for the eight seasons was 191-80.

The 1920 Orioles still had Bentley, and he returned to mound duty, going 16-3 with a league leading 2.10 ERA. He also swung a potent bat with 71 extra-base hits, 20 of which were homers, to go along with a .371 batting average. His 161 RBIs led the league.

Baltimore won its last 25 games to set an IL record. Their season’s record of 110-43 barely eclipsed Toronto’s 108-46 mark. In the best-of-nine JWS, Baltimore defeated American Association champion St. Paul in six games for the first of three JWS titles. Bentley’s two homers won Game One, 5-3. He let his arm do the work in Game Three, winning 9-2 to put the Birds within two games of the series win.6 After the Saints broke into the win column in Game Four, the teams traveled to Minnesota. Bentley was back on the mound, winning 6-5 in Game Five, a triumph marred by fan hostility to umpire Otis H. Stocksdale for calling Lawry, who had bunted, safe at first in an inning where the Orioles scored the game’s decisive run. In the same inning, St. Paul pitcher Dan Griner was accused of throwing a shine ball, and a further ruckus ensued.7 The Orioles clinched the series in Game Six. Ogden pitched a 1-0 shutout and Boley’s home run was the only offensive support needed.

Babe Ruth in a borrowed New York Giants uniform, with his former owner Jack Dunn (and Giants player Jack Bentley), before the October 3, 1923, exhibition game between the Giants and the Dunn’s International League Orioles. Ruth, who was a star with the Yankees by then, was enticed to play to be a gate draw. The game’s proceeds went to fundraising for former Giants owner John B. Day and former manager Jim Mutrie. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Babe Ruth in a borrowed New York Giants uniform, with his former owner Jack Dunn (and Giants player Jack Bentley), before the October 3, 1923, exhibition game between the Giants and the Dunn’s International League Orioles. Ruth, who was a star with the Yankees by then, was enticed to play to be a gate draw. The game’s proceeds went to fundraising for former Giants owner John B. Day and former manager Jim Mutrie. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

In 1921, Dunn added pitcher Tommy Thomas. Thomas racked up 105 wins in five seasons with the Orioles before being traded to the White Sox for Maurice Archdeacon late in the 1925 season. The deal was announced on September 12, 1925, and Thomas, after spending the balance of the season with Baltimore, joined Chicago for the 1926 season.8

Bentley batted .412 with 24 home runs and 120 RBI. His batting average is the IL record. He set a league record of 246 hits that still stands and led in doubles (47), total bases (397) and slugging average (.665). The 24 homers were a league record at the time. On the mound, Bentley was 12-1 with a 2.35 ERA. Being left-handed and with these statistics, it is not surprising that he was starting to be called “The Babe Ruth of the Minors.”9

Baltimore lost the 1921 JWS to Louisville in eight games.

The 1922 Orioles had a phenomenal record (115-52) thanks in large part to pitchers who could hit. In addition to Bentley (13-2; .351 batting average and 22 homers), the staff included Parnham (16-10; .315 batting average and six homers), Ogden (24-10; two homers), Thomas (18-9; two homers), and Harry Frank (22-9; one homer).

Grove went 18-8 with a pair of doubles amongst his 13 hits. He remained in Baltimore for 1923 and 1924, compiling a combined record of 53-16. He made his major-league debut in 1925 with the Philadelphia Athletics, and hung around for 17 Hall-of-Fame seasons, compiling a 300-141 record for the A’s and the Boston Red Sox.

Bentley hit at least 20 homers in each season from 1920 through 1922. What did he do as a pitcher? A none-too-shabby 41-6. It was his pitching that attracted John McGraw of the Giants who obtained Bentley for $72,500. Bentley was used mostly as a pitcher by the Giants going 40-22 from 1923 through 1925, but did manage to bat .329 with four homers, and went 5-for-12 (.417) in the 1923 and 1924 World Series.10 In 1923, his .412 batting average (28-for-68) set the one-season mark for hitting by National League pitchers. His overall average that year was .427 as he pinch-hit on 22 occasions, going 10-for-21 with a walk.

The Orioles returned to the Junior World Series in 1922, defeating St. Paul, five games to two.

The 1923 Orioles went 111-53 and won the IL pennant by 11 games. The core of the team — Bishop, Boley, Jacobson, Lawry, and Maisel — was still around, and Bishop led the league in homers with 22. In 1921, Dunn had signed 19-year-old Dick Porter, whom he kept locked up through 1928. Porter batted .316 in 1923. It was the first of six consecutive seasons in which he batted at least .316.

Jimmy Walsh was the new first baseman in 1923 and batted .333. He was a 35-year-old veteran who had parts of six seasons in the majors, and had joined Baltimore in 1922, batting .327. It was his second go-around with Baltimore. He had been with the team from 1910 through 1912.

Grove was 27-10 with a league leading 330 strikeouts. Parnham, who had rejoined the team in 1922, was 33-7 in his last great season. In the JWS, Baltimore lost to Kansas City in nine games.

In 1924, Baltimore went 117-48 and finished 19 games ahead of Toronto. Grove’s pitching (26-6) and Porter’s batting (.363) led the league. The key acquisition that season was George Earnshaw. Dunn held on to Earnshaw until 1928, when the Athletics met Dunn’s price of a reported $80,000. Baltimore lost to St. Paul in a JWS that took 10 games to complete, there being one tie.

In 1925, three pitchers won at least 28 games. The team’s leader in wins was Thomas with 32. Earnshaw, in his first full season, won 29. Ogden won 28. Baltimore’s 188 homers were tops in the league. In the JWS, Baltimore defeated Louisville in eight games.

The dynasty would yield ten inductees to the International League Hall of Fame in a steady stream of inductions between 1948 and 1963, with an eleventh, Grove, added in 2008 (after his induction to Cooperstown). Dunn’s Orioles would never again have the glory of those seven great seasons.

ALAN COHEN has been a SABR member since 2010. He serves as Vice President-Treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter and is datacaster (MiLB First Pitch stringer) for the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Colorado Rockies. His biographies, game stories and essays have appeared in more than 40 SABR publications. Since his first Baseball Research Journal article appeared in 2013, Alan has continued to expand his research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946-1965) from which 88 players advanced to the major leagues. He has four children and eight grandchildren and resides in Connecticut with wife, Frances, their cats Morty, Ava, and Zoe, and their dog, Buddy.

SIDEBAR 1

Orioles’ Place on All Time Minor League Team Ranking

|

Year |

Place |

|

1921 |

2nd |

|

1924 |

5th |

|

1920 |

9th |

|

1922 |

15th |

|

1923 |

19th |

|

1919 |

35th |

Source: Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, The 100 Best Minor League Teams of the 20th Century

SIDEBAR 2

Orioles Inductees to the International League Hall of Fame

|

Year |

Name |

|

1948 |

Thomas |

|

1950 |

Dunn |

|

1952 |

Ogden |

|

1954 |

Boley |

|

1955 |

Jacobson |

|

1956 |

Earnshaw |

|

1957 |

Parnham |

|

1958 |

Bentley, Walsh |

|

1959 |

Maisel |

|

1963 |

Porter |

|

2008 |

Grove* |

*Also inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Sources

In addition to Baseball-Reference.com and the sources cited in the notes, the author used:

“Bentley Goes to Red Sox: World Champions Grab Oriole First Sacker in Draft,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1917, 9.

“Orioles of Old Could Probably Whip Big League Teams Today,” Salisbury Times, April 17, 1953, 12.

Foreman, Charles J. “Orioles Mark Time Waiting for Saints,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1920, 3.

Notes

1 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, The 100 Best Minor League Teams of the 20th Century (Parker, Colorado, Outskirts Press, 2006).

2 Darrell Hanson, “Joe Boley,” SABR BioProject.

3 “Fritz Maisel an Oriole,” Baltimore Sun, March 30, 1919, 9.

4 “Jack Bentley Rounds Out Orioles’ Infield for Dash to the Pennant,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 23, 1919, 11.

5 “Slugging Miners are Meek Before Lefty Groves: Wins His Second Game for Orioles,” Baltimore American, July 5, 1920, 4.

6 The Sporting News, October 14, 1920, 8.

7 Earl Arnold, “Wrangling and Horseplay Mark Orioles Fourth Win Over Saints, 6-5,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 14, 1920, 24.

8 “White Sox to Get Tommy Thomas from Orioles,” Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), September 12, 1925: 12.

9 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, The 100 Best Minor League Teams of the 20th Century, (Parker, Colorado, Outskirts Press, 2006).

10 Nelson “Chip” Greene, “Jack Bentley,” SABR BioProject.