Baseball Club Continuity: Keep Your Eyes on the Ball

This article was written by Mark Armour

This article was published in 2000 Baseball Research Journal

For how many ballclubs did Willie Mays play? To answer this question, a casual fan would need a baseball encyclopedia like Total Baseball and some knowledge of club histories. In the “Player Register” of Total Baseball, Mays’s entry indicates the club for which he played in a particular year with a “tag” (in 1951 he played for “NY-N” indicating the New York franchise of the National League). Reading Mays’s complete entry, you can see that Mays moved from New York (NY-N) to San Francisco (SF-N) in 1958, and then back to New York (NY-N) in 1972. Missing are the facts that he did not really switch clubs in 1958 — the Giants moved from New York to San Francisco — and that the New York club for which he played in 1972 was a different club (the Mets) than the one for which he played in the 1950s (the Giants).

Most readers of a baseball encyclopedia know the story of Willie Mays, but might not be so knowledgable about the clubs of Bid McPhee or Deacon McGuire. Consider the baseball encyclopedia reader in the year 2100. Would he not read Tim Salmon’s record and be apt to think that he moved from California (Cal-A) to Anaheim (Ana-A) in 1997? Would he not likely conclude that Jeff Cirillo left the Milwaukee AL club (Mil-A) in 1998 to move across town to join the Milwaukee NL club (Mil-N)?

Confusions about club continuity in the nineteenth century are more prevalent both because it was a long time ago and because there were more complicated issues involved. In fact, modern sources do not agree on some of the problems that this study addresses. Nonetheless, this article is an attempt to enumerate the club movements and league shifts and name changes that have occurred in all of major league history. Where sources disagree, I will try to explain the disagreement while selecting one side over the other. The definition of a club is a tricky thing to get a handle on and is at the heart of some of the disagreements that arise about club continuity. In a recent issue of Nineteenth Century Notes, the newsletter of SABR’s nineteenth century committee, Frederick Ivor-Campbell defines a team as “the players, managers, and coaches, the people who actually play the game,” and a club as “the organization and the people who make it up: directors, administrators, staff, [and] players.” This article deals mainly with the club, the organization itself, which is the entity that links the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

This study includes the six officially recognized major leagues and the National Association.

| League | Years |

|---|---|

| National Association (NA) | 1871-1875 |

| National League (NL) | 1876-present |

| American Association (AA) | 1882-1891 |

| Union Association (UA) | 1884 |

| Players’ League (PL) | 1890 |

| American League (AL) | 1901-present |

| Federal League (FL) | 1914-1915 |

The National Association had no central authority to control membership. A club paid the $10 entry fee and became a member in good standing. There was no limit to the number of clubs, nor were poor clubs kept from joining. If a club decided not to complete its schedule, it dropped out and its remaining games would not get played.

The National League was formed, in part, to end this chaos. In doing so it created the notion of a baseball “franchise,” a legal right granted by the league to a club to field a team in a particular city. The league had the authority to control who its member clubs were and where they played. All future major leagues would operate in this manner.

Clubs that switched major leagues

When the Milwaukee Brewers moved to the National League in 1998, it had been 106 years since a club had switched leagues. In the nineteenth century, when there were leagues coming and going, switching was common. The Brewers’ move is unique in that it is the only instance in which two healthy leagues cooperated in the switch.

Of the eight clubs that formed the National League from 1900 through 1961, only two actually began their major league play in the National League: Philadelphia and New York (now San Francisco) in 1883. The other six began play in other leagues. Boston (now Atlanta) and Chicago began play in the National Association. Pittsburgh, Brooklyn (now Los Angeles), Cincinnati, and St. Louis began play in the American Association.

There have been three different National League clubs in St. Louis. All three transferred from different leagues. The first club, a holdover from the NA, was a charter member of the NL but lasted only two years. The second St. Louis club in the National League had been the 1884 Union Association champions before being absorbed into the NL after the UA’s demise. It moved to Indianapolis in 1887. The third club was a member of the AA for all ten years of its operation, moved to the NL in 1892, and plays in St. Louis today.

The Boston club that won the Players’ League championship in 1890 moved to the American Association when the PL went under, won the AA championship in 1891, and was bought out during the merger of the AA and NL.

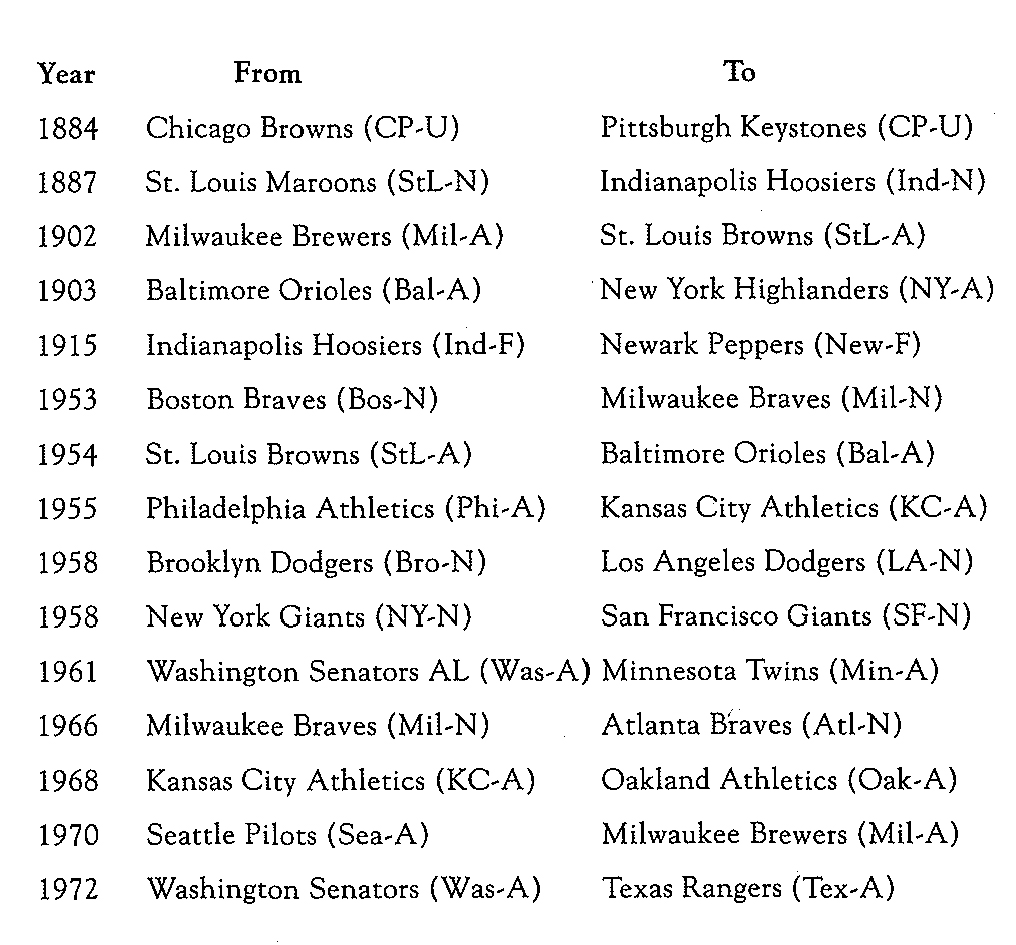

Clubs that switched cities

In the nineteenth century, a club that was having financial problems did not normally move to a different city. Usually, the club would fold and be replaced by a completely different organization, often one that had been playing in a minor league. There were two exceptions, and a few others that are open to interpretation.

In 1877, the NL Hartford Dark Blues played their home games at Brooklyn’s Union Grounds, which had been used in 1876 by the New York Mutuals, since expelled from the league. Despite playing all but a few home games in Brooklyn, the club continued to call itself “Hartford.” Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella’s The Ball Clubs refers to them as the Brooklyn Hartfords, but other contemporary and modern sources disagree with that designation. The 1878 Spalding’s Guide refers to them as Hartford. Total Baseball uses the tag Har-N in both years. All other sources used for this study refer to them as Hartford.

After the 1882 season, the NL voted to drop both Troy and Worcester from the League in favor of New York and Philadelphia. In a recent National Pastime article, Ray Miller claims that the facts support the argument that the Troy club moved to New York. Marshall Wright’s Nineteenth Century Baseball agrees. Noel Hynd’s history of the New York Giants, The Giants of the Polo Grounds, is more persuasive. John Day, the owner of the new New York franchise had a roster to fill and he raided a few of the players from the defunct Troy club, including Roger Connor, Buck Ewing and Mickey Welch. Troy did not move to New York, nor was there any agreement that the New York club would get first crack at Troy players. The Troy club resigned from the league under pressure from league officials and was dissolved while New York was building its team.

The 1884 Chicago UA club moved to Pittsburgh in August. The team lasted eighteen more games before folding. Total Baseball uses the tag CP-U for this team. The move of the AL Baltimore club to New York in 1903 is open to interpretation. The Baltimore club had completely dissolved in the latter half of 1902 and was being run by the league. The franchise was shifted to New York, but the 1903 Highlanders bore no resemblance to the 1902 Orioles.

Indianapolis was the 1914 Federal League champion, and is thus the only pennant winner to move.

Two other clubs moved after finishing with better than .500 records. The 1957 Dodgers and the 1965 Braves were both winning teams. In fact, the Braves were a winning team all thirteen seasons they were in Milwaukee. The Athletics were a losing team all thirteen years they were in Kansas City.

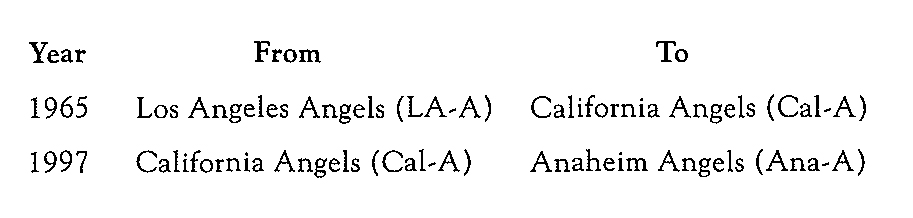

Clubs that changed names without moving

For the past century, major league clubs have commonly been referred to as a city (or state) name accompanied by a nickname. In the nineteenth century, team names were not so consistent. For example, Ivor-Campbell’s article on “Team Histories” in Total Baseball refers to the Pittsburgh club (of the AA and subsequently NL) as “the Allegheny Club” until 1891, when it finally became Pittsburgh. The annual Reach’s Guide (the official guide of the AA) referred to the club as Allegheny as long as it was in that circuit. Spalding’s Guide (the official guide of the NL) referred to it as Pittsburgh as soon as the club joined the National League in 1887. Most modern sources refer to the team as Pittsburgh, regardless of league.

There have been two occasions on which a club’s name change has caused a new “tag” to be used in the encyclopedias, which could cause the casual researcher to conclude that there are two clubs when there is really only one. Coincidentally, both changes involve the same club.

The Angels moved to Anaheim in 1966, one year after they became known as California and thirty-one years before they became known as Anaheim.

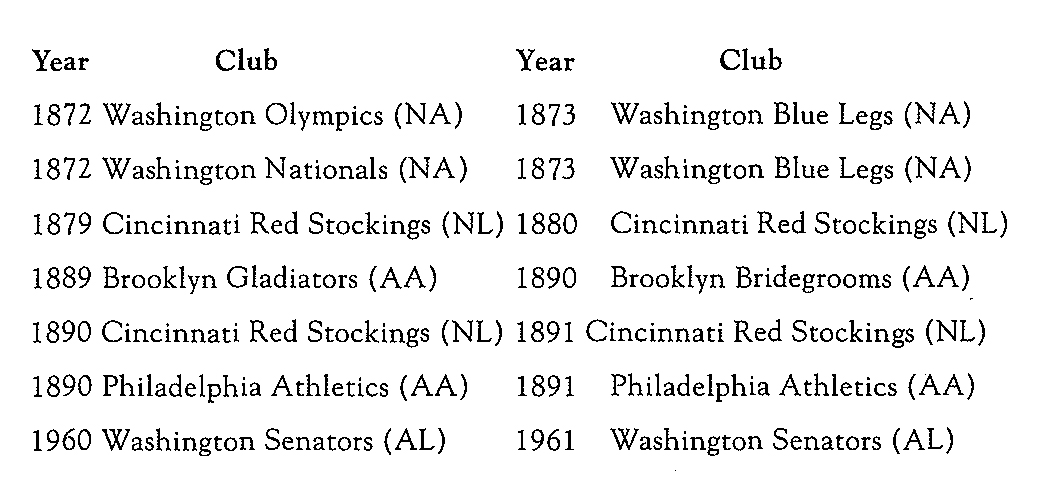

Same city, same league, consecutive years, different team

Sometimes a club has disbanded or left a city or league, and has been replaced by another club in the same city and league. A casual researcher could mistakenly conclude that the two clubs are the same. Here we will need to carefully draw on the distinctions between a team and a club.

One of the trickier club continuity conundrums of the NA era involves the various Washington clubs. There were two Washington clubs in 1872 (the Olympics and the Nationals) and one in 1873 (variously the Blue Legs, the Nationals, or the Washingtons). Ivor-Campbell’s “Team Histories” chapter in Total Baseball considers the 1873 club a continuation of the 1872 Nationals. Other sources consider it a new club or a merger of the two 1872 clubs. Total Baseball (and other encyclopedias) uses a different tag (Was-n) for the 1873 club than for either 1872 club (Oly-n and Nat-n). The lax rules of entry in the NA make the problem a difficult one. The organizers of the 1873 club (without a reserve clause), started from scratch to assemble their team, and ended up with a couple of players from each of the 1872 teams, but mainly with new players.

The first NL Cincinnati franchise (1876-80) was represented by three different clubs. The first one folded in June 1877 and was replaced two weeks later by a new club that retained virtually all the same players and inherited the record of the previous club. It seems apparent that a contemporary baseball fan might not have bothered understanding the fact that the ownership of the club had changed. (After the season, the NL voted to void the results of the 1877 Cincinnati season. The 1878 Spalding’s Guide does not list the Cincinnati club in its official records. All modern sources have readmitted Cincinnati to the record books). The new club folded after the 1879 season and was replaced by a third club that retained only three players. This new club, in fact, fielded a new team. (For an excellent summary of this franchise, see Ivor-Campbell’s recent article in Nineteenth Century Notes.)

The 1889 Brooklyn AA club moved to the NL and was replaced in 1890 by a new Brooklyn AA team.

The 1890 Philadelphia club was disbanded in favor of the Philadelphia club that had played in the Players’ League in 1890.

After the 1890 season, the Cincinnati NL club gained entrance into the Players’ League, which soon dissolved. In the meantime, the NL had granted entrance to a new Cincinnati club. The erstwhile PL club first attempted to join the AA, but subsequently dissolved, which allowed the new NL club to sign up virtually all of its players. Nonetheless, a Cincinnati fan would likely have felt that he was rooting for the same team.

The 1960 Senators moved to Minnesota and were replaced with an expansion team.

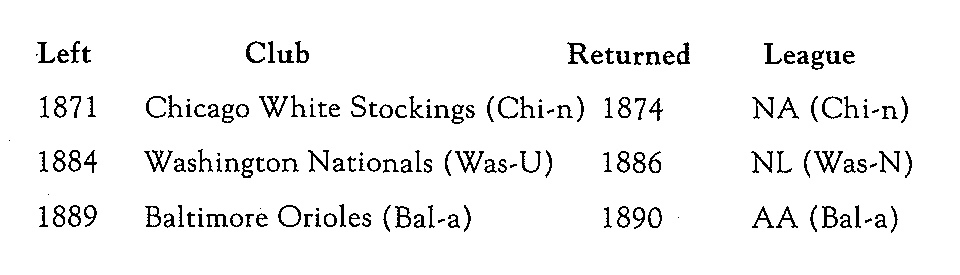

Clubs that left the major leagues and returned

It is important to remember that clubs that entered the major leagues in the nineteenth century were not necessarily brand new — they may have been an existing club that played the previous year in a minor league. Similarly, a club that left the major leagues often played in the minor leagues the next year. Although these transitions are beyond the scope of this article, a related issue does concern us here. There have been a few occasions when a club left the major leagues and later returned.

The White Stockings collapsed after the 1871 season when the great Chicago Fire destroyed their ballpark, their offices, their uniforms and several players’ homes. They took two years off, then returned to the NA in 1874. They remain in Chicago today.

As with the 1872 and 1873 Washington clubs, there is confusion about the relationship between the 1873 and 1875 clubs. Ivor-Campbell’s “Team Histories” chapter in Total Baseball considers the 1875 club a continuation of the 1873 Nationals. Other sources disagree, though it is probably an academic exercise due to the rules of entry in the NA.

After the collapse of the UA, the Nationals played in the Eastern League for one year before joining the NL in 1886.

The Orioles quit the American Association after the 1889 season after a dispute with AA authorities. They played in the Atlantic Association in 1890, but answered the call to return to the AA late in the year to replace the Brooklyn club.

Clubs that folded in midseason and were replaced During the National Association era, clubs often failed to finish the season. Due to the nature of the league these clubs were never replaced, though on at least one occasion a club (1871 Brooklyn Eckfords) entered the league midyear to complete a disbanded club’s schedule. These games did not count in the standings.

Since the NA era, there have been several occasions on which a club disbanded in midseason and was replaced by a new club, usually one already playing in another league. These clubs began playing without inheriting their predecessors’ won-loss record.

Altoona was the smallest post-NA city in major league history (approximately 25,000) and played only twenty-five games (6-19). The club folded so early that the UA had no minor leagues to raid, so the Kansas City club was quickly formed.

The 1884 Milwaukee Brewers won the Eastern League, then moved over to finish out the UA season for Pittsburgh (which had moved from Chicago). The Brewers were probably one of the better teams in the league, finishing 8-4.

The St. Paul Apostles (2-6) never played a home game.

The short-lived Richmond AA entry in 1884 was the first major league club from the former Confederacy. The second was the Houston Colt 45’s in 1962.

Clubs bought out by, or merged into, another existing club Several times in major league history, a folding club has managed to sell out its assets, including some or all players, to another club before going under. In some of the following cases, sources differ about whether one club bought out the other’s assets, or whether there was a true merger.

The owners of the Cleveland Blues sold out to the St. Louis Maroons, but most of the best Cleveland players jumped to Brooklyn’s AA club before the deal could be consummated.

The two Philadelphia clubs merged after the 1890 season but the resulting club was made up mainly of players from the PL club even though the club ended up in the AA.

Four other PL clubs were amalgamated with their NL counterparts as part of the PL collapse.

The three 1899 “mergers” were a result of “syndicate” ownership, which had taken hold in the NL. In each of these cases, the clubs had been owned by the same entity, so when the NL contracted from twelve clubs to eight, it was just a question of transferring the best players from one club to another. For example, Louisville “traded” Honus Wagner, Fred Clarke, Tommy Leach, Rube Waddell, Deacon Phillippe, and others to Pittsburgh for a much less impressive package of players. A few weeks later, the NL bought out the Louisville franchise.

The 1915 mergers were part of the agreement that dissolved the Federal League.

Conclusions

In 1876, there was one major league that played in eight cities: New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Louisville, and Hartford. In 1900, there was one major league that played in a remarkably similar list of eight cities — Pittsburgh and Brooklyn had replaced Hartford and Louisville. In the intervening twenty-four years, there had been a vast turnover in the major leagues, with three leagues and dozens of clubs coming and going. The 1900 National League alignment lasted fifty-three years. The 1903 alignment of the new American League lasted almost as long.

But based on the game’s recent history, no sensible baseball fan in 1903 could have imagined that the two eight-club leagues would remain intact and in the same cities for the next half-century.

MARK ARMOUR writes software, worries about the Red Sox, and conducts baseball research in his hometown of Corvallis, Oregon.

Sources

Dewey, Donald, and Acocella, Nicholas, The Ball Clubs, HarperPerennial, 1996.

Hynd, Noel, The Giants of the Polo Grounds, Doubleday, 1988.

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick and Silverman, Matthew, “Team Histories,” Total Baseball, Sixth Edition, Total Sports, 1999.

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick, Nineteenth Century Notes, 99:1, SABR, Winter 1999.

Miller, Ray, “Pre-1900 NL Franchise Movement,” The National Pastime, Number 17, SABR,1997.

Nemec, David, The Beer and Whiskey League, Lyons and Burford, 1994.

Nemec, David, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Baseball, Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Pietrusza, David, Major Leagues, McFarland, 1996.

Reach’s Guide, 1883-92.

Ryczek, William J., Blackguards and Red Stockings, Colebrook Press, 1999.

Seymour, Harold, Baseball: The Early Years, Oxford University Press, 1960.

Spalding’s Guide, 1876-1892.

Thorn, John, et. al., Total Baseball, Sixth Edition, Total Sports, 1999.

Wright, Marshall D., Nineteenth Century Baseball, McFarland, 1996.