Baseball Seppuku? The Role of the Bases-Loading Intentional Walk in the 1999 Playoffs

This article was written by Chris DeRosa

This article was published in 2001 Baseball Research Journal

At the ballpark, when the home team loads the bases, people stand up and cheer. You don’t see many fans slapping their heads, saying, “Rats, now there’s a force at every base. I wish the bases weren’t loaded.” Yet in a surprising number of 1999’s postseason games, the team in the field chose to load the bases on purpose with an intentional walk.

The intentional walk has been under siege for the last twenty years, both from baseball researchers and managers of the Earl Weaver school. Most recently, David F. Riggs looked at what happened in the plate appearances following World Series intentional walks. (“The Intentional Walk,” BRJ 1999, p. 108.) He concluded that handing out free passes was akin to inserting Ted Williams into the opponent’s lineup.

Worse, the outcome of a free pass is not confined to what the next hitter does; it can also set up a big inning. When a team issues an intentional walk, it is betting that it will win a particular match-up, and in order to bring that match-up about, it places itself in a situation where there is greater potential to give up multiple runs. Loading the bases on purpose is a particularly dangerous form of the intentional walk gamble because it permits the pitcher no margin of error. If the pitcher gets behind in the count, the batter knows he has to come in to him, and can sit on a strike.

Despite the dangers, this move proved quite popular in the 1999 postseason. I would have guessed it happened eight or nine times. Would you believe fifteen? Fifteen times a playoff team issued a Bases Loading Intentional Base on Balls (BLIBB), accounting for 39 percent of all postseason intentional walks (38).

Intuitively, it seems like this move fails nine times out of ten. As a fan, I cringe when my team loads them up on purpose, but perhaps that is because the failures are more memorable than the successes. Let’s see how the fifteen postseason gambles worked out in 1999:

ALDS: Yankees vs. Rangers

In Game 1, with the Yanks leading, 3-0, in the bottom of the fifth, men on second and third with two out, Texas gave Darryl Strawberry an intentional walk to load the bases. The Rangers escaped when Jorge Posada lined out (1999 Postseason BLIBB Performance Record: 1-0).

NLDS: Braves vs. Astros

In Game 1, with Houston leading, 1-0, in the top of the fifth, the Braves faced Carl Everett with men on second and third and one out. Everett received an intentional walk to load the bases. It worked out when the next hitter, Ken Caminiti, bounced into a double play. In the top of the ninth, the Braves were still trailing by a run when Jeff Bagwell came to the plate with first and third and one out. Bagwell got the game’s second intentional walk to load the bases. Everett hit a sacrifice fly and Caminiti followed with a three-run homer. The walk may have been irrelevant to the sac fly, but it can hardly be called a success, seeing that Bagwell came around to score (BLIBB: 2-1).

In Game 3, with the series tied and the score knotted, 3-3, Bagwell again came up with first and third and one out. The Braves responded with another intentional walk to load the bases. This time it worked out when Caminiti fanned and Matt Mieske flew out (BLIBB 3-1).

ALDS: Red Sox vs. Indians

This series’ epic Game 5 should long be remembered as a showcase of just how pivotal these intentional walks can be. With the series tied and Cleveland leading, 5-3, in the top of the third, second and third with one out, Nomar Garciaparra came to the plate and received an intentional walk to load the bases. Troy O’Leary cleared the bases with a grand slam (BLIBB 3-2).

Later, Cleveland rallied to tie the score, 8-8, and in the top of the seventh, man on second with one out, again gave Nomar a free pass to face O’Leary. Although this did not load the bases, O’Leary punished them again with a three-run blast. The two walks to Garciaparra arguably wrecked Cleveland’s season and cost skipper Mike Hargrove his job.

ALDS: Mets vs. Diamondbacks

In Game 3, with the series tied and the Mets leading, 4-2, in the bottom of the sixth, second and third with one out, Buck Showalter decided to deal with Edgardo Alfonso via an intentional walk to load the bases. John Olerud promptly followed with a two-run single, then Roger Cedeno knocked in Alfonso, and Darryl Hamilton drove in Olerud and Cedeno, and the game was out of hand (BLIBB 3-3).

In Game 4, with the score tied, 3-3, and two outs in the bottom of the eighth, the D-Backs gave Daryl Hamilton an intentional walk to load the bases, after which Rey Ordonez struck out (BLIBB 4-3).

ALCS: Yankees vs. Red Sox

In Game 2, with New York leading, 3-2, in the top of the eighth, men on second and third and one out, Joe Torre ordered reliever Allen Watson to give pinch hitter Lou Merloni an intentional walk to load the bases. Then Ramiro Mendoza came in, struck out pinch hitter Butch Huskey and got Jose Offerman to fly out to Bernie Williams, and Yankee Stadium exhaled (BLIBB 5-3).

In Game 4, with the Yanks leading the series, 2-1, the Red Sox trailed by a run in the top of the eighth with one away and Chili Davis at the plate. The Sox waved Davis to first with an intentional walk to load the bases in order to face Scott Brosius. They were rewarded when Brosius popped out and Chad Curtis fanned. The next inning, with New York ahead, 5-2, with second and third and one out, the Sox gambled again by giving Tino Martinez an intentional walk to load the bases. Ricky Ledee capitalized with a grand slam, putting the game out of reach (BLIBB 6-4).

NLCS: Braves vs. Mets

In Game 5, a titanic fifteen-inning affair, there were six intentional walks (!) but only one to load the bases. The Mets gave free passes to Chipper Jones (twice), Eddie Perez, Brian Jordan, and Gerald Williams. In the bottom of the fifteenth, the Braves got into the act. Leading by one run with one out, they walked John Olerud to get to Todd Pratt. Unlike the previous five, this one was an intentional walk to load the bases. Pratt squeezed out an unintentional walk to tie the game, and Robin Ventura hit it out of the park to win it. Pratt began celebrating before Ventura reached second, thereby reducing the grand slam to a grand single (BLIBB 6-5).

In Game 6, with Atlanta leading the series, 3-2, and the game, 5-3, in the bottom of the sixth with men on second and third and one out, the Mets gave an intentional walk to load the bases to the original Brian Hunter. Walt Weiss postponed the decision with a comebacker, but then Jose Hernandez singled to left to drive in two runs (BLIBB 6-6).

This game was just getting started. The Mets kept fighting and tied the score, 9-9. In the bottom of the eleventh, fireballing Armando Benitez was finally out of gas and New York summoned Kenny Rogers to pitch. With one out and a man on third, Mets manager Bobby Valentine ordered Chipper Jones to first base (in the NL East race, Jones had slain the Mets almost single-handedly). Brian Jordan then came to the plate with men on first and third and the Mets’ whole misbegotten odyssey of a season on the line. Valentine ordered an intentional walk to load the bases. Back-to-back free passes to juice the bags! Rogers then issued Andruw Jones an unintentional walk to lose the game and end the series (BLIBB 6-7).

Superficially, there seemed to be little advantage in pitching to Andruw Jones (.275 BA, .365 OBP, .483 SA) instead of Brian Jordan (.283, .346, .483); however, Jordan had a better record against left-handers. To gain this platoon advantage, though, the Mets had to put Kenny Rogers into a bases-loaded jam with the pennant in the balance.

World Series: Yankees vs. Braves

In Game 1, with the Yankees up, 4-1, in the top of the eighth, men on second and third and none out, Bobby Cox bypassed Bernie Williams with an intentional walk to load the bases. John Rocker then struck out Tino Martinez and Jorge Posada, but walked Jim Leyritz before fanning Scott Brosius. In this case, the walk didn’t lead to a blowout inning, but the Yankees still scored, and scored only because the bags were full. I’ll call that a no-decision (BLIBB 6-7-1).

In Game 4, Williams came to the plate with no score in the bottom of the third, men on first and third with one out. Determined not to let Bernie beat him, Cox called once more for an intentional walk to load the bases. Martinez foiled the plan with a two-run single, Strawberry went down on strikes, then Posada drove in Williams to punctuate the inning (Final 1999 Postseason BLIBB Performance Record: 6-8-1).

Damage Assessment

The bases-loading intentional walk did not in fact fail “nine times out of ten” in this small sample from the 1999 playoffs. In fifteen tries, the walk-issuing team came away unscathed six times. Nine times the team at bat scored, and seven times it scored multiple runs. Among the big innings were such memorable self-inflicted wounds as the Indians’ loading the bases for Troy O’Leary’s grand slam, which put Cleveland in the hole in Game 5 of the ALDS; the Braves’ setting up Todd Pratt’s fifteenth inning game-tying walk which preceded Ventura’s game-winning long shoe in Game 5 of the NLCS; and the Mets’ returning the favor with their BLIBBs to Hunter and Jordan in the sixth and eleventh innings of the terminal Game 6.

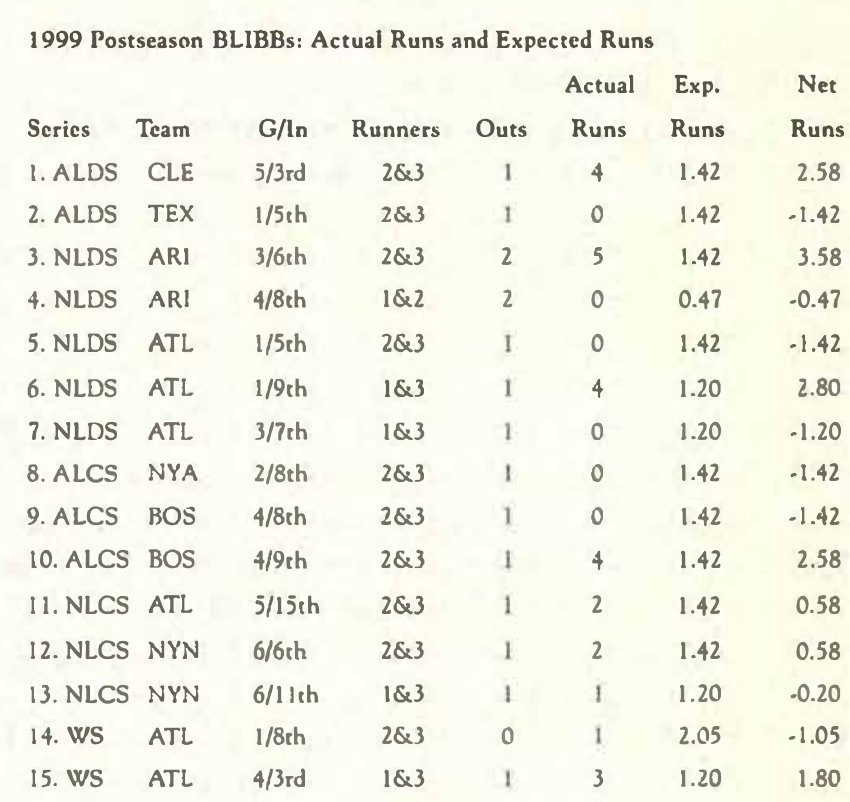

It is important to keep in mind that before a bases-loading intentional walk can occur, there have to be two men on (although the Mets did walk two batters to load the bases in NLCS Game 6). In fifteen second-and-third and first-and-third situations, the team in the field is most likely going to yield some runs no matter what it chooses to do. It is possible to compare how many runs scored after the fifteen BLIBBs to how many runs we might expect to have score based on situational averages. To get the expected runs for each situation, I used the averages compiled over the past five seasons by STATS, Inc.

To be clear, on the chart, the “Actual Runs” are the actual number of runs that scored after the BLIBB. The “Expected Runs” are for the situation before the BLIBB. The “Net Runs” is the theoretical increase or decrease in runs allowed as a result of the move.

All bases-loaded situations expect to yield more runs than any situation without the bags loaded and the same number of outs. Obviously the defensive manager knows that, in general, it is not preferable to load the bases. The question is how they do when they go against the odds.

From the fifteen pre-BLIBB situations, we might reasonably have expected 20.1 runs to score. After issuing the walks, 26 runs scored, a 29 percent increase over the expected scoring. Of course in terms of total runs, the extent of the damage in Cases 11 and 13 is contained by the fact that they involved game-ending plays. On the chart, Case 13 (Rogers walks Jordan) looks like a success, but believe me, it was not. In Case 11, had Ventura circled the bases, 29 runs would have scored after BLIBBs, an increase of 44 percent. Of the fifteen bases-loading intentional walks, nine were issued while the team was behind, two while ahead, and four while tied. The walk-issuing team won only two of the twelve games above.

The bases-loading intentional walk proved an unreliable weapon for 1999’s postseason managers. It would take further research, however, to determine if in a larger sample the move tended to convert potential big innings into actual big innings with the same efficiency.

The funny thing about this move being in vogue now is that the frequency of intentional walks over, all, long stable, is in sharp decline. In 1975, the average NL team gave out 66 free passes and AL teams averaged 45. In 1980, it was 66 in the NL and 46 in the AL. In 1985 it was 65 in the NL and 40 in the AL. Five years later in 1990, it was 66 in the NL and 42 in the AL. Look, however, at what happened to intentional walks during the hard-hitting ’90s: in 1996, the NL average was 52 and the AL average was 44. In 1997, it fell to 45 (NL) and 39 (AL). In ’98 it fell again to 40 (NL) and 30 (AL), before leveling off in 1999 (42 for the NL, 31 for the AL).

Managers are likely changing their habits in direct response to the surge in scoring. When almost anyone can hit it out of the park, it makes less sense to put runners on for free. At the same time, when there are runners on second and third with one out, they seem to be saying, “This is probably going to be a big inning anyway, so I’ll just take a shot with one good matchup.” In the 1999 playoffs, the gamble paid off less than half the time.