Bats, Balls, Boys, Dreams and Unforgettable Experiences: Youth All-Star Games in New York, 1944–65

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

The summer of 1947 was like few others before it in the annals of New York baseball. The month of August welcomed a heat wave as well as young men (ages 16–18) from all over the United States for two events: the Hearst Sandlot Classic and Brooklyn Against the World All-Stars. Each of the contests was in its second year of existence. Max Kase of the New York Journal American had established the Hearst Sandlot Classic in 1946. Hearst papers from 12 cities sent players to face a team of New York’s best. That same year, Lou Niss of the Brooklyn Eagle invited newspapers from around the country to send players to Brooklyn to face Brooklyn’s best.

The initial Hearst Classic was played in 1946 and the New York kids won 8–7 in 11 innings. The second annual Hearst Classic was played August 13, 1947, and produced nine major leaguers. Playing for Ray Schalk’s U.S. All-Stars, which won a lopsided 13–2 decision, were three men who would be reunited in the 1960 World Series: Gino Cimoli, Dick Groat, and Bill Skowron. One of the big blows for the visitors was Skowron’s eighth-inning inside-the-park homer off Rudy Yandoli, the first home run in the history of the Hearst Classic.

A Classic record 31,232 attended the game which featured Babe Didrikson-Zaharias in a golf and baseball exhibition, and a performance by the Clown Prince of Baseball, Al Schacht, who had also performed at the 1946 Hearst game. Even more notable was an appearance by the game’s honorary chairman, Babe Ruth. Ruth took his seat at the start of the third inning of the game and was accorded a standing ovation that stopped the game. His lateness was due to his accepting a series of engagements that would tire the healthiest of men.1

The Hearst Newspapers and the Brooklyn Eagle were not the first publishing entities to sponsor an All-Star baseball game for the youth of America. With newspapers and periodicals being the dominant form of media, sponsoring baseball events was an attempt to increase circulation. In 1944 and 1945, Esquire sponsored All-Star games for 16 to 17-year-old players using an East-West format. The magazine, notorious for its curvaceous “Vargas Girl” caricatures, was seeking to expand into the sports arena.

The August 7, 1944, Esquire All-American Boys Baseball Game featured 29 boys from 23 of the then-48 states and was won 6–0 by the East squad in front of 17,803 spectators at the Polo Grounds. The managers in the game were Connie Mack (East) and Mel Ott (West). The dream itinerary included accommodations at the Hotel New Yorker, a visit to the Statue of Liberty, and an Empire State Building tour with former New York Governor and one-time presidential candidate Al Smith.2 Richie Ashburn from Tilden, Nebraska, caught the final innings and made the game’s last out. He was sent east by the Omaha World-Herald. Tilden has a baseball diamond with a sign over it that reads: “Tilden Memorial Park–Richie Ashburn Field.” Ashburn would return to the Polo Grounds often during his major-league career, covering the expansive center field. In 1962, in his last All-Star appearance, he represented the Mets.3

In 1946, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle began its “Brooklyn Against the World” competition at Ebbets Field. The forces behind the game were Branch Rickey of the Dodgers and Lou Niss, the sports editor of the Eagle. Brooklyn was managed by Leo Durocher, and the World was managed by Hall-of-Famer George Sisler. Henry Tominaga, Lenny Yochim, Roger Breard, Alex Romanchuk, and Joe Della Monica appeared on the “We the People” broadcast on CBS radio.4 After a performance of Oklahoma at the St. James Theater, cast member Beatrice Lynn, who hailed from Flatbush, posed with Chris Kitsos and Joe Torpey of the Brooklyn squad.5

The boys woke to rain on August 7. As afternoon turned into evening the rains stopped. At the ballyard, Brooklyn legend Gladys Gooding sang the National Anthem.6 Also in attendance was Hilda Chester, the most vociferous fan of the Dodgers. Hilda was hard to miss. She came to each game equipped with her cowbells and heckled the opposition with an unmatched fervor. The young “World” players were not spared Hilda’s treatment and Brooklyn won the three-game series, 2–1.7

Playing right field for Brooklyn in the second game of the series was Ed “Lefty” Ford of the 34th Avenue Boys Club in Astoria Queens and Aviation High School in Manhattan. It was his only appearance in the three games. Ford didn’t pitch in BAW but later that summer he would shine.8 1946 was the second year for the Journal-American Sandlot Alliance championship game. At the Polo Grounds on September 28, pitcher Ford allowed only two hits in 11 innings and struck out 18 batters. He led off the bottom of the 11th inning with a double for his team’s first hit, and came around to score the winning run in the 1–0 contest.9 Ford was awarded the Lou Gehrig Trophy as the game’s MVP. A week later, he signed with the Yankees for a $7,500 bonus, and his next game was as a professional. Whitey Ford returned to Ebbets Field to pitch in four World Series and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1974.

BAW events would be held in various formats through 1950 and 10 participants—including Ford, Billy Loes, and Joe Pignatano—played in the big leagues. Even more participants found their success elsewhere, fulfilling the vision of men like Lou Niss and his counterpart from the other side of the East River, Max Kase.

Over 100 of the young men from the Esquire’s, BAW, and Hearst games made their way to the major leagues. At least one player appeared in the World Series in each year from 1949 through 1975, and in the 1957 World Series, seven participants could trace their starts to these games. There were All-Stars galore, 35 in all. For three consecutive years (1957–59), there were eight alums of the Esquire, Brooklyn Against the World, and Hearst programs in each of the All-Star games. And there was at least one alum in every All-Star Game from 1951 through 1978.

Max Kase of the New York Journal American created the Hearst Sandlot Classic in 1946. That year, it was known as the Hearst Diamond Pennant Series. Former ballplayer “Rabbit” Maranville directed the Journal-American Sandlot Alliance, and managed the Journal-American All-Stars. The All-Stars, selected from tryouts held in the leagues that comprised the Alliance, were opposed by the U.S. All-Stars. The visitors were selected by Hearst newspapers in 12 cities from coast to coast, and included representatives from each of the cities. In the first two years, they were managed by Ray Schalk, but Oscar Vitt took over in 1948. For 14 years, Vitt was the lifeblood and face of the U.S. All-Stars. Each year an MVP was selected to receive the Lou Gehrig Award. Five players from these games (including two New Yorkers) would be selected for enshrinement at Cooperstown. Many of the players from around the country would become part of the fabric of big-league ball in New York. Fifteen played for the Mets, 11 for the Yankees, and two went on to lead New York teams to championships in the World Series.

The inaugural Hearst game was played on August 15 and each visitor spent a week in New York, staying at the Hotel New Yorker. The first few days included a Yankees-Red Sox game, a trip to Long Island’s Jones Beach, a reception at Gracie Mansion, the residence of New York’s Mayor, and an evening show at Radio City Music Hall, where the movie Anna and the King of Siam was on the big screen. On Tuesday, there was a trip around Manhattan Island by boat, which included a view of the Statue of Liberty, followed by a Broadway show—that year it was Showboat. On the eve of the game, the boys travelled to West Point and dined on steak at the Bear Mountain Inn. The final highlight: U.S. All-Stars played in front of major league scouts and got to meet with major league players. The game was won, 8–7, in eleven innings by the New Yorkers in front of 15,289 fans.

Billy Harrell, from Troy, New York, was the first black player to appear in the Hearst Classic, playing in 1946 and 1947. In 1946, he starred at the All-Star game held at Albany’s Hawkins Stadium on June 15, with three singles and a double in six at-bats, driving in two runs.10 When he played in the Hearst Classic for the first time, heavyweight champion Joe Louis bought 1,000 tickets for the game, and these tickets were distributed by The Amsterdam News to children in Harlem.11 After playing in the Hearst Classic, he attended Siena College, starring on the basketball court as well as the baseball diamond. Harrell was signed by Hank Greenberg of the Indians in 1952, and played with the Tribe in parts of the 1955, 1957, and 1958 seasons.

Baseball lost Babe Ruth on August 16, 1948, and the Hearst game on August 26 was played in his memory. Joe DiMaggio stepped in as honorary chairman, and each of the players received an autograph from the Yankee Clipper. Dick Groat’s one vivid memory of his two games in New York was standing outside in the rain across from St. Patrick’s Cathedral during Ruth’s funeral on August 19.

There were three Hall-of-Famers in the history of the Hearst Classic. In 1951 Al Kaline set the standard for excellence. He had completed his sophomore year of high school, and at age 16 years, 7 months, and 20 days was one of the youngest players to play in the Hearst Classic. He was accompanied to New York by Baltimore News-Post writer Frank Cashen, who would go on to orchestrate the ascendance of the New York Mets during the 1980s. Kaline went 2-for-4 in the Hearst Classic with a single and an inside-the-park homer that sailed over the center fielder’s head. In the field, he was equally adept, making five good plays and gunning down a runner at third base.12 In 1960, long time U.S. All-Star manager Ossie Vitt said, “I could tell he was one of the best prospects I’d ever seen the first time I saw him. He had those wrists with a snap in them, the poise, hustle, and attitude, and how he could throw and run.”13

Ron Santo was the starting catcher for the U.S. team in 1958, and his hitting display in the practice leading up to the game was beyond impressive. Four of his first five swings were for homers. After starring as an infielder in his early years of high school, he caught as a senior. That fall, Santo was signed for a bonus estimated at $25,000 by the Chicago Cubs. One of their scouts, Dave Kosher, had been watching Santo since his sophomore year in high school, and, with Cubs head scout Roy “Hardrock” Johnson, corralled Santo. After signing with the Cubs, Santo was converted back to third base in his Texas League days. He made his major-league debut with the Cubs in 1960, less than two years after playing in the Hearst Classic, and had a 15-year major league career. He was named to nine All-Star teams, and batted .277 with 342 home runs. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2011.

Joe Torre played in the 1958 Hearst game. Torre was a bona fide hitter for the Brooklyn Cadets, but he was significantly overweight and was not considered major league material at either first or third base. His older brother Frank convinced him that his only way to the majors would be as a catcher, and he made the switch. Within a year, he was signed by the Milwaukee Braves. In 1961, he batted .278 and finished second in the rookie-of-the-year balloting. The Braves traded him to St. Louis in 1969, and he had an MVP season in 1971. At the end of his playing career he took over the managerial reins of the Mets as player-manager before switching to managing full time. After several mostly disappointing years managing the Mets, Braves, and Cardinals, he joined the Yankees in 1996. During his 12 years in the Bronx, his teams made it to the postseason every year, winning 10 divisional championships, six American League pennants, and four World Series. He left the Yanks after the 2007 season and managed the Dodgers to Divisional Championships in 2008 and 2009. On December 9, 2013, he received word that he had been elected to the Hall of Fame.

Davey Johnson, who would manage the Mets to the World Series in 1986, first attracted scouts at San Antonio’s Alamo Heights High School. He had just completed his first year at Texas A&M when he played in the 1961 Hearst game. In the regional game in San Antonio he had earned his way to New York with a fielding gem and a line-drive single. He was very highly thought of by Assistant Manager Buddy Hassett who commented, “I like his wrist action and the way he whips the bat around so fast.”14 After the Hearst game, he went back to Texas A&M for his sophomore year, where he played shortstop for “the greatest coach in the world, Tom Chandler, a real classic who taught me real respect for the game, and gave me an opportunity to show what I could do.”15 He signed with Baltimore after his sophomore year. He went on to appear in four World Series, was named to four All-Star teams, and won three Gold Glove Awards.

Tommy Davis won two National League batting titles and batted .302 with 16 homers and 73 RBIs in 154 games for the Mets in 1967. He was listed as Herman Davis from Brooklyn’s Boys High School when he played in the Classic in 1955. Hurricane Connie put a damper on things and the game was stopped after 4½ innings with the New Yorkers winning, 4–3. He signed with Brooklyn, but when Davis was ready for the big leagues, the Dodgers were in Los Angeles. In 1962, with the Dodgers, he returned to the Polo Grounds on Memorial Day, when 55,704 fans saw Davis’s Dodgers sweep the Mets in a doubleheader. In the first game, Davis went 2-for-5 with a pair of RBIs. A knee injury in 1965 set him back, and the knee would continue to give him problems for several years. However, he reemerged as a Designated Hitter in 1973 with Baltimore.

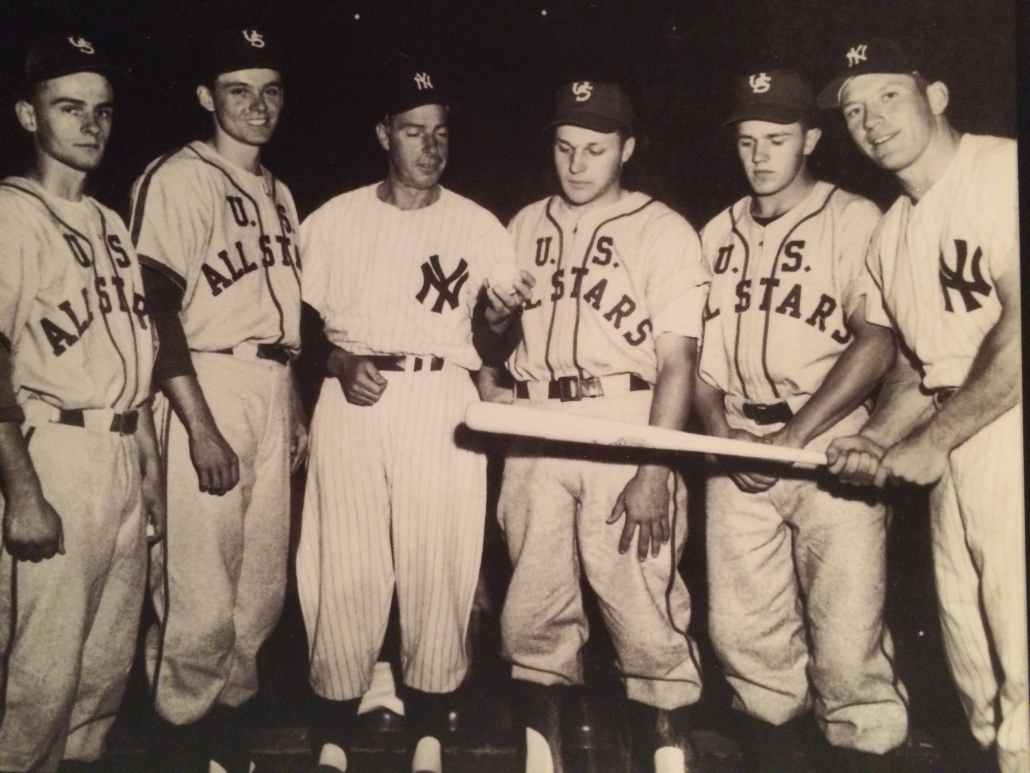

1957 Hearst Sandlot Classic. Mantle and DiMaggio partook in a pre-game home run hitting contest (with Willie Mays). To the left of DiMaggio is Ron Madden (2B) and John Mitchell (P) of Chicago. The boys between DiMaggio and Mantle are Thomas Hollman (C) and Frank Heinicke (1B) of Pittsburgh. (Both Hollman and Mitchell eventually signed with the original Washington Senators.) (PHOTO COURTESY OF CHRIS HOLLMAN)

Tony Kubek represented Milwaukee in 1952. His father had played with the Milwaukee Brewers during the 1930s. Tony did not sign right away, as he was only 16 when the game was played in 1952. He gained great experience playing sandlot ball, and caught the eyes of scouts, including Lou Maguolo of the New York Yankees.16 Kubek’s first spring training with the Yankees was in 1954. Five years after appearing in the Hearst game, Kubek was the American League Rookie of the Year.

There were many stars in the 1962 Hearst game which was stopped by curfew after 11 innings and over four hours of play, tied 4–4. It was the only tie in the history of the series. The game’s MVP, New York shortstop Joe Russo, made some sparkling plays in the field. He went on to graduate from St. John’s University and served as the school’s baseball coach for 23 years.

Ron Swoboda got to visit the Mets clubhouse at the Polo Grounds in 1962. In the Hearst game, a very nervous Swoboda went 0-for-4. The following summer Ron was on a Baltimore team that finished second in the All-American Amateur Baseball Federation championship game in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.17 After the game in Johnstown, Swoboda was signed by Pete Gebrian, a scout for the New York Mets.18 He made his major-league debut in 1965. He spent nine seasons in the big leagues and is best remembered for his game-saving catch in the ninth inning of the fourth game of the 1969 World Series.

The 1969 Mets also featured a man who had represented San Antonio in the 1961 game. During the week leading up to the 1961 Hearst Game, Jerry Grote roomed with fellow San Antonian Davey Johnson. Johnson remembers sitting on Grote’s shoulders while the future Mets catcher was doing pushups to strengthen his arms. Grote signed with Houston in 1962 for a reported bonus of $20,000 and was traded to the Mets in one of a series of trades that would lead the Mets to glory in 1969. He played twelve seasons in Queens, was named to two All-Star teams, and has a rightful place in the Mets Hall of Fame.

Most of the players did not make it to the majors, but their stories are compelling just the same. Howie Kitt of Oceanside, New York, was all over the local papers as a kid. In 1960, Kitt, who had just completed his freshman year at Columbia University, was the starting pitcher for the Journal-American All-Stars. In his three innings of work the left hander allowed no hits. His seven strikeouts (six of them were consecutive) set a Hearst record. After five minor league seasons in the Yankees organization, he left baseball behind him with no regrets and forged a career as an economist. His career took him to the top echelons of antitrust and trade regulation matters.19

Over the years, between tryouts, elimination games, and the big events in New York, over one million boys participated in these programs.

ALAN COHEN has been a SABR member since 2011, serves as Vice President-Treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter, and is the datacaster (stringer) for the Hartford Yard Goats. He has written more than 35 biographies for the SABR BioProject, and has contributed to several SABR books. He has expanded his research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946–65), the annual youth All-Star game which launched the careers of 88 major-league players. He graduated from Franklin and Marshall College with a degree in history. He has four children and six grandchildren and resides in West Hartford, Connecticut, with his wife Frances, one cat (Morty), and two dogs (Sam and Sheba).

SOURCES

In addition to the sources in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and the following newspapers:

Baltimore News-Post

Milwaukee Sentinel

San Antonio Light

The author also interviewed the following persons for this story.

Dick Groat: 5/21/3014

Billy Harrell: 1/22/2014

Jim Henneman: 07/07/2014

Davey Johnson: 03/10/2015

Howie Kitt: 05/19/2016

Tony Kubek: 5/23/2014

Jim McElroy: 06/06/2014

Joe Russo: 01/22/2015 and 05/27/2017

Ron Swoboda: 1/07/2014

NOTES

1 Edgar C. Greene, “Babe Still ‘Do as I Please’ Guy,” Chicago Herald-American, August 14, 1947: 24.

2 Bill Leiser, “As Sports Editor Bill Leiser Sees It,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 3, 1944: 1-H.

3 Mark Kram, “Welcome to Tilden Nebraska: Ashburn grew up in a Quiet, Safe, and Friendly Place, and It Hasn’t Changed,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 26, 1995.

4 “Boro, World Pilots Announce Starting Lineups Tomorrow,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 5, 1946: 10.

5 “Brooklyn Born and Bred,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 6, 1946: 13.

6 James Murphy, “Brooklyn All-Stars Seek 2nd Win Tonight,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 8, 1946: 1, 15–16.

7 “Array of Notables See Brooklyn Triumph,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 8, 1946: 15.

8 Fay Vincent, We Would Have Played for Nothing (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2008), 149–50.

9 “34th Avenue Nine Takes Met Crown with 1–0 Victory: Ed Ford Outstanding Star of 11 Inning Test at Polo Grounds,” Long Island City Star Journal, September 30, 1946: 12.

10 Dick Walsh. “District’s Stars Rally in 10th for 10-7 Victory,” Albany Times-Union, June 16, 1946: B-7.

11 “Negro on Hearst Sandlot Nine; Louis Tix for Free,” The Amsterdam News, August 3, 1946: 10.

12 Al Jonas, “U. S. Stars Defeat New York Team in Sandlot Classic,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1951: 28.

13 Morrey Rokeach, “Vitt Picks Hearst Stars: Kaline, Loes Among Grads of Sandlot Tilts,” New York Journal-American, August 14, 1960: 29.

14 Rokeach, “Vitt Impressed by Star Nine’s Power, Speed,” New York Journal-American, August 19, 1961: 15.

15 Edward Kersch, “Davey’s Destiny,” Cigar Afficionado, September, 1999.

16 Joseph Wancho. “Tony Kubek” SABR BioProject.

17 L. D. McReady, “Brooklyn Cadets top Baltimore in AAABA Title Tilt,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963: 39.

18 Len Pasculli. “Ron Swoboda” SABR Bio-Project.

19 “Antitrust and Trade Regulation Specialist Howard Kitt Joins CRA International’s New York Office; Founder of NERA’s Antitrust Consultancy Offers Wealth of Experience,” Business Wire, June 2, 2005.