Big Leaguer: A Small-Time Film with Big-Time Personalities

This article was written by Frederick C. Bush

This article was published in From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors

Most casual baseball fans are familiar with such well-known movies as the Lou Gehrig biopic The Pride of the Yankees, the myth-making twosome of The Natural and Field of Dreams, and the irreverent Bull Durham, but there are numerous films that have been largely forgotten even by diehard baseball and film aficionados. The 1953 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer release Big Leaguer falls into the latter category of cinema which is, in all likelihood, due to the fact that the real-life stories of some individuals involved in the project are of more interest than the characters and events in the film itself.

Later in his career, director Robert Aldrich called Big Leaguer “a nineteen-day marvel,” intended to be little more than theater-filler for MGM.1 Aldrich went on to greater fame as director of movies like The Dirty Dozen (1967) and the football-themed The Longest Yard (1974), but Big Leaguer marked his theatrical-film debut. In addition to cutting his teeth in cinema on the set of this film, Aldrich had the opportunity to work with longtime Hollywood star Edward G. Robinson, who was best known for his gangster roles in such films as Little Caesar (1931) and Key Largo (1948).

In his heyday, Robinson would have had no part of such a low-budget effort, but this was the first major-studio film role he had been offered in three years due to the fact that he had run afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee.2 Robinson was twice called to testify before the HUAC, in 1950 and 1952. Though he sought to distance himself from his liberal political activities in the 1930s and 1940s, he was “effectively ‘graylisted’ from Hollywood,” which resulted in film producers being hesitant to hire him.3

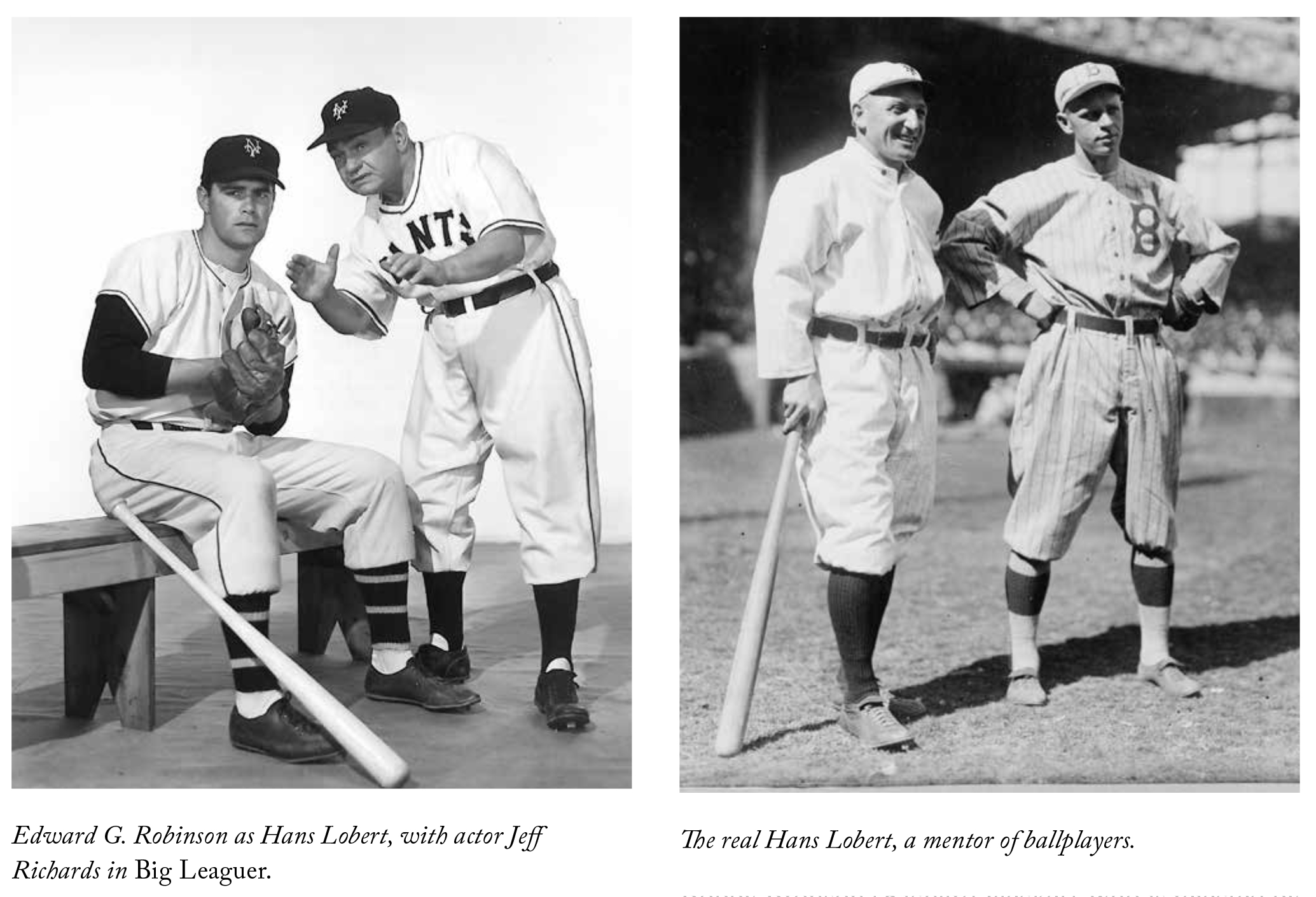

Robinson was also known to be a baseball fan, which likely helped him to embrace his role as Hans Lobert, a former Deadball Era infielder who was working as a scout and instructor for the New York Giants at the time the film was made. Though Robinson’s name still gave clout to his film, Aldrich developed some doubts about the casting choice. He recalled, “Eddie Robinson was a marvelous actor and a brilliant man, but he was not physically coordinated. He would walk to first base and trip over home plate.”4

Robinson’s lack of agility stood in contrast to the real-life John “Hans” Lobert, whom he was portraying. Lobert was born on October 18, 1881, and began his major-league playing career with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1903. The first Pirates player Lobert met was future Hall of Famer Honus Wagner, who dubbed the new rookie “Hans Number Two” because they shared the same first name.5 Lobert played for five different teams over the course of a 14-year career in the majors; he batted .274 with 1,252 hits and 316 stolen bases.

Lobert went on to become a baseball lifer. After his playing career ended, he coached the West Point baseball team from 1918 to 1925 before returning to the New York Giants – the last team for which he had played – as a coach. In 1934 he became a coach with the Philadelphia Phillies, another of his former teams, and ended up as the team’s manager for the 1942 season. The Phillies’ 42-109 record that year was, according to Lobert, “enough to end a beautiful friendship.”6 After two years as a coach for the Cincinnati Reds, Lobert returned to the Giants in 1945 and worked for the franchise until his death on September 14, 1968, by which time his life in Organized Baseball had spanned a total of 66 years.

Although Hans Lobert was a real person who did indeed work for the New York Giants and the movie was filmed at the Giants’ training complex in Melbourne, Florida, Big Leaguer is a fictional film that indulges in several of the clichés that abound in much of baseball cinema. Robinson’s Hans Lobert character runs a training camp that allows him to scout and to train prospects for the New York Giants. The movie alternates between faux-documentary narration about the training camp and the true action involving the characters.

The clichés involve the conflicts surrounding the primary prospects in the camp. Adam Polachuk (Jeff Richards) is an immigrant’s son whose father believes he is studying law while he is actually pursuing a baseball career. To complicate matters further, Polachuk falls in love with Lobert’s niece, who is portrayed by Vera-Ellen in the only non-dancing role of her career. Tippy Mitchell (Bill Crandall) is the son of a former star first baseman and is unable to tell his father that he would rather be an architect than a ballplayer. Lastly, there is pitching prospect Bobby Bronson (Richard Jaeckel), who is rejected by the Giants and then is signed by the rival Brooklyn Dodgers. Lobert is worried that Bronson will come back to haunt him by fulfilling his potential with the Dodgers, and he becomes concerned that the Giants might dismiss him or end his training program altogether. As Hollywood would have it, however, all turns out well in the end.

Though the film’s content is trite, considerable effort was expended to portray the baseball scenes as realistically as possible. For one thing, Lobert was retained as technical adviser to tell Aldrich and the actors how things should play out and so that Robinson could learn to mimic his mannerisms. Lobert was paid the grand sum of $2,000 for providing his expertise.7 In addition to that, several former ballplayers had minor roles, including future Los Angeles Dodgers executive Al Campanis, Bob Trocolor, and Tony Ravish; Jeff Richards had also been a baseball prospect at one time, but an injury had derailed his shot at a professional career. Lobert recalled that the ballplayers received $10 per day for their roles and that another $10 was added if they actually had a speaking part in a particular shot.8

The most notable player to appear in Big Leaguer was Hall of Fame pitcher Carl Hubbell, who had won 253 games and the 1933 World Series with the Giants. According to Lobert, Hubbell received $5,000 for his cameo role as himself, a paycheck that was commensurate with his status in comparison to that of Lobert and the other ballplayers on the set.9

Big Leaguer received mixed reviews upon its release. One critic called it “nothing more than a double-bill entry,” while Variety magazine wrote that Robinson was “good as the camp founder and believable in the hokum that has been mixed in with fact.”10 The Giants’ training camps were certainly a fact, and Lobert continued to conduct them, even in as far away a locale as the Virgin Islands. In November 1958 the Giants sent Lobert to St. Thomas and St. Croix for two weeks to work with the Virgin Islands Baseball Clinic Committee to plan instructional classes.11 Hollywood may not have ventured out on a limb with Big Leaguer’s content, but the real Giants franchise showed that it was willing to go much farther than Melbourne, Florida, in search of new talent.

FREDERICK C. BUSH and former big-leaguer Hans Lobert, who is featured in his article, have much in common: 1) They both lived in Pittsburgh, PA for parts of their lives; 2) Lobert played briefly for the Pirates, and Bush later cheered for the same franchise; 3) Lobert is featured in Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times, and Bush has read Ritter’s book; 4) Lobert coached the baseball team at the US Military Academy (Army) at West Point for eight years, and Bush grew up as the son of a career US Army soldier. Add in the fact that both men hail from German ancestry, and it becomes obvious that Bush is practically a latter-day Lobert, who was fated to write about his predecessor for this book.

Notes

1 Robert Bock, The Edward G. Robinson Encyclopedia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 43.

2 Hal Erickson, The Baseball Filmography, 1915-2001, 2nd edition (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 92.

3 Ibid. According to Robert Aldrich, being “graylisted” was worse than being blacklisted: “Since Robinson was not overtly accused of anything, the HUAC would not give him a chance to publicly defend himself and thus encourage producers to hire him.”

4 Bock, 44.

5 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times, enlarged edition (New York: William Morrow, 1984), 189.

6 Ritter, 185.

7 Henry W. Thomas and Neal McCabe, eds., The Glory of Their Times, audiobook, by Lawrence S. Ritter (HighBridge Company, 1998), CD.

8 Ibid. It may be of some interest that Bing Russell, the father of actor Kurt Russell and grandfather of former major leaguer Matt Franco, appeared in an unbilled role. (See https://imdb.com/name/nm0751032/). Bing Russell later owned the Portland Mavericks, an independent minor-league baseball team, from 1973-77. The Mavericks lived up to their name and were featured in a 2014 documentary film, The Battered Bastards of Baseball.

9 Ibid.

10 Bock, 44.

11 “’Hans’ Lobert of Giants to Hold Clinic,” Virgin Islands Daily News, November 18, 1958.