‘Bigger than Sinatra’: Sandy Koufax in Hollywood

This article was written by Vince Guerrieri

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

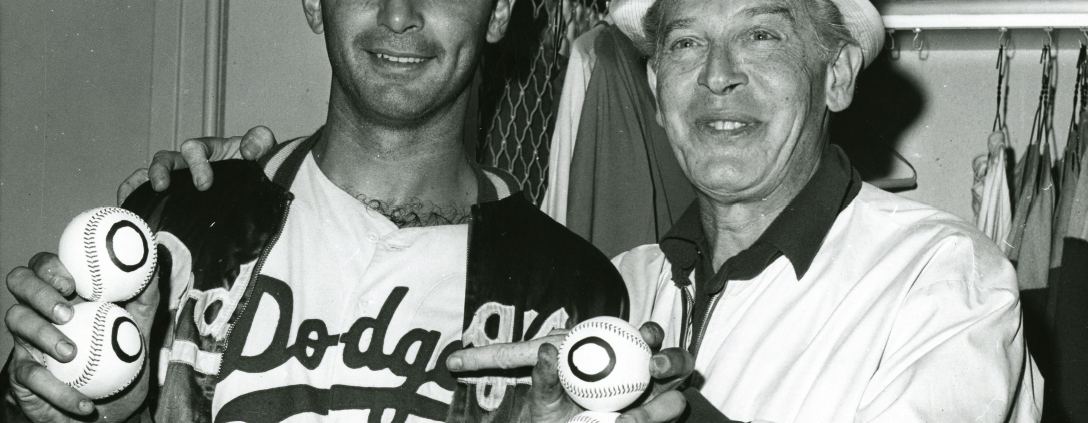

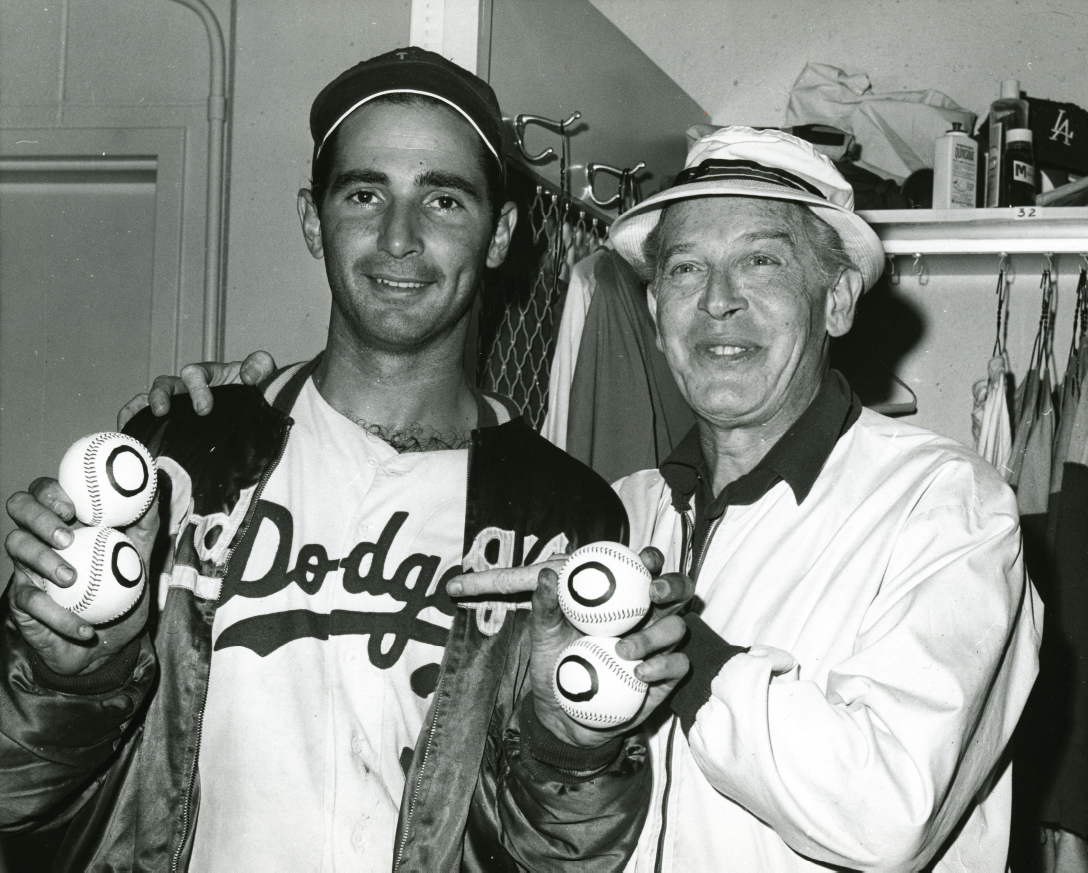

Famed comedian Milton Berle greets Sandy Koufax after the left-hander threw his perfect game against the Chicago Cubs in 1965. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

In the post-World War II era, New York City was effectively the baseball capital of the nation.

Not only was it the home of the commissioner’s office (baseball’s initial commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, kept an office in Chicago; his successor Happy Chandler, a Kentucky native, had his office in Cincinnati), but it was home to three major-league teams, all of which were successful. In fact, from 1947 through 1958, every World Series featured at least one of New York City’s teams, with the Yankees and Giants meeting in 1951 and the Yankees and Dodgers meeting six times.

In the 1950s New York City was also the hub for the nascent medium of television. Displayed at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, television was also seen as a potential sports broadcasting medium as well. In fact, the first American sports broadcast was a Princeton baseball game at Columbia University in 1939.1 Broadcast networks occupied Midtown skyscrapers with business offices and studios.2

But by the end of the 1950s, there were seismic shifts for both baseball and television, and both involved a move west. After the 1957 season, the Dodgers decamped for Los Angeles, bringing the Giants with them to San Francisco. (Before too long, there would be an American League team in Los Angeles as well, as baseball expanded to head off a potential third league.) The beloved Bums of Brooklyn had given way to a new team, more oriented toward speed and pitching, with Maury Wills setting a record for stolen bases in 1962 and dominant pitching by Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax.3

Koufax and the Dodgers became a dynasty in the 1960s, winning two World Series and losing a third. Their success and proximity to the new center of the television industry made them darlings of Hollywood, none more so than Koufax himself, who threw four no-hitters and won three Cy Young Awards. His roommate Dick Tracewski said Koufax was “bigger even than Sinatra.”4

When the film industry moved west in the early twentieth century, there were technical considerations.5 Los Angeles offered more temperate weather and an abundance of natural sunlight, both aids to filmmaking. Television production also moved west because of new technology.

Initially, television was live, for the simple reason that there wasn’t a lot of technology available to record and rebroadcast shows. Film was used for some shows, most notably I Love Lucy,6 ensuring that it would be around for generations.7 Some programs were recorded on kinescope, which is essentially filming a television screen, at least initially for rebroadcast on the West Coast.8

Magnetic tape had been around for audio purposes since the 1920s, and by the 1950s a workable solution was found to use tape recording for video as well as audio, leading to television shows being recorded and played at any time.9 In 1953 some 80 percent of network television was broadcast live. By 1960 that number had shrunk to 35 percent, and very little of that was scripted television.10

Perhaps most importantly, the movie studios were moving into television production themselves. Columbia Pictures recycled the name of its prewar cartoon production company, Screen Gems, into its TV production company, starting first with advertisements and then with original series like Father Knows Best, I Dream of Jeannie, and The Partridge Family. When Walt Disney opened his eponymous theme park in California in 1955, it was televised live, and Disney became a Sunday evening television staple for generations. In fact, by 1959 Warner Bros. supplied one-third of ABC’s prime-time schedule.11

There has always been a connection between athletes and Hollywood. The Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League team included celebrities among their minority owners,12 including Gene Autry, who parlayed that into ownership of the American League team that came to Los Angeles in 1961. Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, buddies in a series of Road movies for Paramount, were minority owners of the Indians and Pirates respectively.13 And the Los Angeles Dons, a football team in the new All-America Conference in 1946, were named for their owner, movie star Don Ameche.

But the arrival of the Dodgers marked a new era in the marriage between sports and celebrity. Milton Berle and Doris Day could be spotted at Dodgers games. An exhibition game against Hollywood actors–started initially with the Hollywood Stars–became an even bigger deal with the Dodgers in the 1960s.14

And suddenly, TV roles abounded for Dodgers players in general and Koufax in particular. He played bit parts on shows like 77 Sunset Strip and Bourbon Street, and played himself in cameo roles on Dennis the Menace and Mister Ed,15 where he notably gave up a home run to the title character, a horse.16

Koufax had become that breed that, while common now, was rarer in the 1960s: an athlete whose fame transcended his sport. “To a gushy Hollywood columnist he is Clark Gable, Gregory Peck and William Holden rolled into one,” said a 1963 New York Times profile that said Koufax “has the world by the tail.”17

Although they both had limited roles in a variety of TV shows, Koufax and Drysdale also tried to use Hollywood as a bargaining chip during their 1966 holdout.18 While they were waiting for a new contract, Paramount said the pitchers had signed for roles in a crime drama called Warning Shot. Drysdale denied the signing, but said he and Koufax were keeping their options open.19 The two did start rehearsals for the movie, but ultimately re-signed with the Dodgers (in a deal that former Dodgers farmhand and TV star Chuck Connors helped broker20), and didn’t take part in the film, which was released in 1967, the year after Koufax retired.

The great irony is that for as much as Hollywood took to Koufax as the Dodgers’ ace, a post-playing career in television did not materialize. Following his retirement after the 1966 season, he signed a million-dollar contract with NBC, becoming host of The Sandy Koufax Show, a 15-minute program that aired prior to the network’s Game of the Week on Saturday. It did not go well. “I’m not sure where it would be more accurate to say I saw Sandy go on the tube or down it,” one wag said.21 By many accounts, he improved as the years went on, but finally in 1973, the year after his Hall of Fame induction, Koufax quit NBC with four years left on his contract.22

“He kept saying this is the best job in the world but ‘it’s not for me,’” said NBC vice president Carl Lindemann.

“I’m just not suited for it,” Koufax said.23

is a journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He’s the secretary/treasurer of the Jack Graney SABR Chapter, and has contributed to the SABR BioProject, the SABR Games Project, and several SABR anthologies. Additionally, he’s written about baseball history for a variety of publications, including Ohio Magazine, Cleveland Magazine, Smithsonian, and Defector. He can be reached at vaguerrieri@gmail.com, or found on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.

Notes

1 David J. Halberstam, “Eighty years ago today, NBC experimented with the first ever telecast of a sporting event,” Sports Broadcast Journal, May 17, 2019. https://www.sportsbroadcastjournal.com/eighty-years-ago-today-nbc-experimented-with-the-first-ever-telecast-of-a-sporting-event/ The first televised sporting event in the world was the 1936 Olympics. (David J. Halberstam is not the author David Halberstam, who was noted for his writing on the Vietnam War, but who also wrote several books on sports. He was killed in an auto accident in 2007.)

2 NBC, then as now, is a tenant at Rockefeller Center, nicknamed 30 Rock. CBS’s headquarters, not far away, was called Black Rock for its dark facade. The headquarters for ABC, regarded at least initially as an also-ran, was sometimes called “Little Rock.”

3 Wills debuted with the Dodgers in 1959, by which time they were in Los Angeles. Both Koufax and Drysdale debuted for the Dodgers while they were still in Brooklyn, Koufax as a “bonus baby” in 1955 who signed with his hometown team, and Drysdale the following year. Drysdale was a contributor in the Dodgers’ final season in Brooklyn; Koufax was seen as more of a project.

4 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: Harper Collins, 2009), 382.

5 There were other reasons as well, chief among them a desire to stay out of reach of Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company. Further reading: https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2021/03/thomas-edison-the-unintentional-founder-of-hollywood/.

6 Leigh Allen, “Filming the ‘I Love Lucy’ Show,” American Cinematographer, January 1952. https://theasc.com/articles/filming-the-i-love-lucy-show.

7 At Lucille Ball’s death, it was held as an article of fact that I Love Lucy was always on somewhere in the world.

8 The first coast-to-coast broadcast was a speech by President Harry Truman in 1951. “This Day in History: President Truman Makes First Transcontinental Broadcast,” https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/president-truman-makes-first-transcontinental-television-broadcast.

9 Alex Marsh, “A History of Videotape, Part 1.” https://blogs.library.duke.edu/bitstreams/2017/07/27/history-videotape-part-1/. The article also notes an unfortunate consequence: To save money, a lot of the tapes were reused, wiping out the earlier content. The entire first decade of Johnny Carson’s stint on The Tonight Show (as well as much of his predecessors, Jack Paar and Steve Allen) are lost to history because of it.

10 Ralph G. Giordano, Pop Goes the Decade: The Fifties (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing, 2017). Accessed online February 26, 2024.

11 Kerry Segrave, Movies at Home: How Hollywood Came to Television (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999), 35.

12 See also Stephen M. Daniels, “The Hollywood Stars,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1980. https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-hollywood-stars/.

13 Crosby also owned minority shares in the Tigers, which he was allowed to keep with a special ruling by Commissioner Ford Frick. Kevin Reichard, “Celebrity Owners and Major League Baseball,” Ballpark Digest, March 7, 2019. https://ballparkdigest.com/2019/03/07/celebrity-owners-and-major-league-baseball/.

14 Mark Langill, “The Movie Hollywood Stars Game,” The National Pastime, SABR, 2011. https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-movie-hollywood-stars-game/.

15 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVm-HwAkVp8&t=41s.

16 Mister Ed featured a cameo by Leo Durocher, who was by then on the Dodgers’ coaching staff. He also made appearances on several shows in the 1960s, most notably giving Herman Munster a tryout on The Munsters.

17 “Man With Golden Charm: Sanford (Sandy) Koufax,” New York Times, October 3, 1963: 40.

18 Drysdale had an even lengthier list of television credits, and he went on to a career as a broadcaster after his playing days.

19 Associated Press, “Drysdale Hints at Compromise; He, Koufax Weigh Film Pact,” New York Times, March 17, 1966: 48.

20 Jeff Katz, “Everybody’s a Star: The Dodgers Go Hollywood,” The National Pastime, SABR, 2011. https://sabr.org/journal/article/everybodys-a-star-the-dodgers-go-hollywood/.

21 Charlie Maher, “Sandy Koufax’ New Life,” Sport, July 1967.

22 Among Koufax’s difficulties, as described in his SABR biography, were imparting his knowledge to a generalized audience and his discomfort being critical of players he’d played with or against.

23 Sandy Padwe, “Koufax Leaves TV, ‘Just Not Suited for It,” Newsday (Suffolk edition), February 23, 1973: 119.