Bill Veeck and the St. Louis Browns

This article was written by Greg Erion

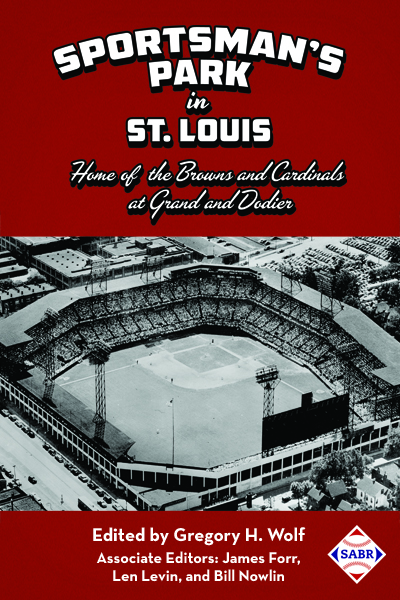

This article was published in Sportsman’s Park essays

By 1951 the Browns were decidedly moribund. They had been last in the American League in attendance every year since 1946 and the usual question one asked before the start of the season was whether they might finish in seventh or eighth place. Underfinanced, Charles and William DeWitt wanted out of what they saw as a no-win situation. The only way they had been able to continue running their team was through the sales of their more promising players, but by 1951 even this option was thinning out. They began to quietly let word get out that they were looking to sell the team.

By 1951 the Browns were decidedly moribund. They had been last in the American League in attendance every year since 1946 and the usual question one asked before the start of the season was whether they might finish in seventh or eighth place. Underfinanced, Charles and William DeWitt wanted out of what they saw as a no-win situation. The only way they had been able to continue running their team was through the sales of their more promising players, but by 1951 even this option was thinning out. They began to quietly let word get out that they were looking to sell the team.

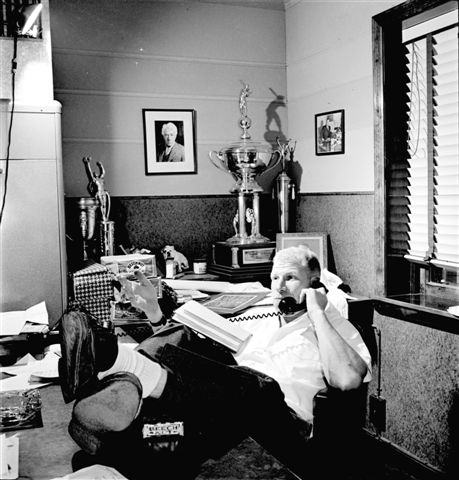

Their plan to put the Browns up for sale soon came to the attention of Bill Veeck. One of the most colorful characters in baseball history, Veeck grew up with the sport – his father, William Veeck Sr., had been president of the Chicago Cubs in the 1930s. Young Veeck followed in his father’s footsteps, first as treasurer of the Cubs and then as part-owner of the Milwaukee Brewers in the Double-A American Association. Taking on the financially strapped Brewers in midseason 1941, Veeck and co-owner Charlie Grimm soon turned things around. Offering a precursor of things to come, Veeck staged numerous promotional events ranging from offering free lunches to giveaways of pigeons and blocks of ice. He introduced night games at the Brewers’ Borchert Field and offered morning games for night-shift defense workers during World War II.1 Attendance nearly tripled over the previous season. During five years of ownership Grimm and Veeck won three pennants.

Veeck first attempted to get into the major-league market in late 1942, by trying to purchase the Philadelphia Phillies. Once gaining ownership, his plan was to fill the roster with players from the Negro Leagues – four years in advance of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier. Quite probably because of this, the league owners awarded the Phillies to another prospective buyer.2

In 1946 Veeck was able to purchase the Cleveland Indians. He immediately began to work his promotional skills on the team. Efforts ranged in all directions from introducing Ladies’ Day, refurbishing Municipal Stadium, and offering radio broadcasts of the games – all the while talking with fans and getting their take on how to improve the team’s draw and popularity. While these efforts were radical departures from the staid habits of Veeck’s predecessors, in 1947 he initiated an even greater change, signing Larry Doby, the first African American to play in the American League.

In 1948 Veeck added legendary Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige to the roster. The presence of Doby and Paige proved vital in helping the Indians win the pennant and the 1948 World Series. Performance on the field generated success at the box office. A major-league record 2,620,627 fans attended Cleveland’s regular-season games. In 1945, the year before Veeck purchased the team, just 558,182 fans had come through the Indians’ turnstiles. One year after winning the Series, Veeck sold the team. He was getting a divorce and settlement terms demanded that he jettison the Indians.

A little over a year and a half later, with his divorce settled and newly remarried, Veeck jumped at the chance to get back in the game as an owner. Negotiations commenced in early May. By June Veeck secured an option on the DeWitts’ shares in the Browns.3 His ability to purchase the team depended on his obtaining 75 percent ownership of the club. According to The Sporting News, Veeck and his partners needed to meet that percentage threshold under Missouri law to “liquidate the present Browns set-up, pay off minority stockholders and form a new corporation entirely owned by Veeck and his associates.”4 The DeWitts held 58 percent of the shares; Veeck was given 12 days to purchase 114,000 shares and gain the remaining 17 percent he needed. The day before the deadline, Veeck was 8,500 shares short of his goal but a last-minute purchase of 8,572 shares from a Browns board member on July 3 put him over the top.5

Including Veeck, 16 members of the syndicate ended up owning 222,000 of the Browns 275,000 shares – giving them slightly over 80 percent control of the club.6 Most versions of the deal pegged Veeck and his syndicate as having purchased the team for $1,750,000. The DeWitts had bought the club for approximately $1,000,000 in 1949.7

A day after meeting the deadline Veeck went to the ballpark. “I moved all over the park and talked to every fan I could reach. … These are people we are going to serve. I want to know what they want, what they like, what they think of the ball club.”8 What fans thought of the club was probably not positive, as the Browns were swept in a doubleheader by, ironically, the Cleveland Indians. The double loss entrenched their hold on last place; they were the worst team in major-league baseball. Of Veeck’s decision to purchase the Browns, John Lardner wrote, “Many critics were surprised to know that the Browns could be bought because they didn’t know the Browns were owned.”9

Veeck immediately went to work on several fronts to upgrade the ballpark, increase interest in the Browns and improve the team. Responding to women’s complaints that Sportsman’s Park needed a thorough cleaning, Veeck arranged for the St. Louis Fire Department to hose down the upper deck.10 Within days during a doubleheader on July 6, he announced that soft drinks and beer were on the house; he personally handed out several buckets of cold beer while visiting the bleachers.11 As if these activities were not enough, Veeck reached out to a then highly regarded Browns minor leaguer named Frank Saucier, who had decided to leave the game rather than play for the salary he was offered. Veeck tracked down Saucier, who was working for an oil company, and signed him to a contract. Never mind that Saucier would fail with the Browns. That Veeck would go all out to improve his team impressed the fans. Over the next several months, Veeck crisscrossed the region drumming up support for the team.

Veeck immediately went to work on several fronts to upgrade the ballpark, increase interest in the Browns and improve the team. Responding to women’s complaints that Sportsman’s Park needed a thorough cleaning, Veeck arranged for the St. Louis Fire Department to hose down the upper deck.10 Within days during a doubleheader on July 6, he announced that soft drinks and beer were on the house; he personally handed out several buckets of cold beer while visiting the bleachers.11 As if these activities were not enough, Veeck reached out to a then highly regarded Browns minor leaguer named Frank Saucier, who had decided to leave the game rather than play for the salary he was offered. Veeck tracked down Saucier, who was working for an oil company, and signed him to a contract. Never mind that Saucier would fail with the Browns. That Veeck would go all out to improve his team impressed the fans. Over the next several months, Veeck crisscrossed the region drumming up support for the team.

These were minor efforts compared with subsequent endeavors Veeck put forth that season. On August 19 the Browns hosted the Detroit Tigers for a doubleheader. Between games a celebration marking the 50th anniversary of the founding of the American League was scheduled to take place. The event included a procession of 1901 vintage automobiles and comic performances by baseball clown Max Patkin. As a finale a giant cake rolled out on the field commemorating the event. A midget dressed in a Browns uniform popped out of the cake. All this was considered below Veeck’s promotional standards.

Then the second game began and the midget, one Eddie Gaedel, was announced as a pinch-hitter for the Browns.12 After verifying that Gaedel had signed a viable contract, the umpires allowed him to bat. Tigers pitcher Bob Cain walked Gaedel on four pitches, whereupon he was removed for a pinch-runner. Veeck’s action proved controversial, especially to fellow baseball owners, whose approach to the game was decidedly more conservative than that of the Browns’ lively owner. Brash as Veeck was, he brought excitement to the game with this and numerous other events, promotions, and efforts to lure fans into the ballpark. Less than a week later, on August 24, Veeck arranged to let fans manage a game. Manager Zack Taylor sat in a rocking chair near the dugout and watched as fans picked a lineup and made strategic decisions during the contest.13 The Browns finished last but attendance rose from approximately 4,000 per game to over 5,000 after Veeck took over.

Veeck’s long-term goal was to outhustle the Cardinals promotionally. He had a daunting task ahead of him. The Cardinals were a much better team, they had a legacy of winning, and their players, like Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst, were huge draws. However, Redbirds owner and financial expert Fred Saigh was a novice in baseball circles. Veeck felt that through consistent promotions, endless publicity, and gradually building the Browns into a contending team he would succeed drawing away Cardinal fans over time.

During the 1952 season Veeck followed this strategy and to some extent succeeded. Attendance increased from 293,270 to 518,796 – a substantial jump. Of equal importance, Cardinals attendance dropped from 1,013,429 to 913,113 – still a decided edge over the Browns but moving in the right direction from Veeck’s perspective. On the field, the Browns marginally improved, winning a dozen more games to finish seventh.

Veeck’s biggest challenge going into 1953 was to increase the team’s revenue. It was estimated that the Browns would have to draw approximately 850,000 fans to break even.14 Promotions to draw fans to the park were improving attendance, but slowly. Seeking an additional source of income, Veeck overreached. After the 1952 season ended, appreciating the possibilities of televised games, he proposed to fellow American League club owners that they share radio and television revenue with visiting teams. Veeck’s proposal, admittedly self-serving given the Browns’ dearth of popularity, was shot down 7 votes to 1, each team deciding to negotiate separate deals. At that point Veeck retaliated, saying that a “no pay, no television” policy would be implemented. Teams would not broadcast their games from St. Louis unless the Browns got part of the earnings when playing games on the road. Other teams, including the Yankees, Red Sox, and Indians, countered Veeck by refusing to schedule profitable night games. Veeck had taken on owners he would soon learn he could ill afford to antagonize.

As Veeck was involved in these maneuverings, a rapidly developing situation took place in the National League that would have a profound overall effect on baseball history and on the St. Louis Browns specifically.

The Browns’ departure from St. Louis was ironically set in motion by misfortune that befell the Cardinals when Fred Saigh, owner of the team, was indicted for income-tax evasion. Pleading no contest to the charges, Saigh expected to pay a fine for his actions. Instead, on January 28, 1953, he was not only fined $15,000 but also sentenced to 15 months in jail. On hearing this, Saigh realized his ownership of the team was finished. “This means, of course, that I will have to dispose of the Cardinals. There is no way I can stay in baseball.”15 Within days Saigh met with National League President Ford Frick to establish plans for divesting himself of the franchise. He was given until February 22 to make a deal to sell the Cardinals. After that date, they would come under the control of a board of trustees.16 Once it became known that Saigh had to sell, offers came in from numerous groups, including one that could have involved shifting the Cardinals to Houston, Texas.17

Several weeks later, two days before the February 22 deadline, Saigh sold the team to the Anheuser-Busch brewing company. His intent in selling to Anheuser-Busch was to keep the team in St. Louis. In describing the transaction, Saigh said, “During the past weeks I have had serious offers for the Cardinals but all of them involved moving the club away from St. Louis.” One of the most serious later offers involved a consortium of Milwaukee businessmen intent on shifting the team to their city; one of the attractions: the recently completed County Stadium, which had a capacity of over 34,000.18 Milwaukee baseball fans did not have to wallow in disappointment at losing the Cardinals for long. The sale of the Cardinals to the cash-rich brewery set off a series of repercussions within the baseball world that would bring Milwaukee its own team and force the Browns out of St. Louis.

When Veeck heard that Anheuser-Busch had purchased the Cardinals, he realized that his efforts to promote his team had no chance to succeed against the financial juggernaut. When August “Gussie” Busch, president of the brewery, came to Sportsman’s Park for the first time as owner of the Redbirds, Veeck welcomed him: “Glad to see you. But I’m afraid you’re going to offer us a little difficult competition.” Busch’s smiling, “You’re right” confirmed that the Browns could succeed only if they moved elsewhere.19

There were two viable options for Veeck to pursue. Both Baltimore and Milwaukee had built ballparks of sufficient capacity to support major-league baseball. Veeck’s inclination was to move to Milwaukee, the site of his earlier accomplishments with the American Association Brewers. But there was a significant snag to that option. Lou Perini, owner of the Boston Braves, held territorial rights to baseball in the Milwaukee region.

Perini wanted out of Boston; in 1952 his Braves drew just 281,278 fans – the worst in the major leagues, losing nearly $600,000 for the year 20 Realizing he could not compete with the Red Sox, Perini considered his options. Eager to move the Browns to Milwaukee, Veeck offered Perini $750,000 for the rights to the market. Perini stalled him off.21 Early in March, just weeks after Saigh sold out to Anheuser-Busch, Perini announced that the Braves were moving to Milwaukee.

Thwarted by Perini’s action, Veeck turned his attention to seeing if he could shift the Browns to Baltimore, now his only viable option.

Baltimore had hosted a major-league team during the first two years of the American League’s existence only to lose the franchise to New York in 1903. Over the ensuing years, even while hosting the International League’s Baltimore Orioles, the city of Baltimore yearned to regain major-league status. Baltimore’s existing Memorial Stadium gave it an advantage over other cities seeking a major-league franchise. Recently rebuilt, the 31,000-capacity ballpark was ready for big-league competition.22

While Veeck maintained that the major turning point for his deciding to move was Anheuser-Busch’s decision to purchase the Cardinals in the spring of 1953, he had sent out feelers to Jack Dunn III, who owned the minor-league Orioles, in the fall of 1952.23 Dunn was receptive to giving Veeck territorial rights for the move if he could have an ownership stake in the franchise.24

Even earlier, in the summer of 1952, Veeck initiated discussions with Baltimore city officials concerning Memorial Stadium. Baltimore’s Mayor Thomas J. D’Alesandro Jr. and local attorney Clarence Miles, who were spearheading efforts to gain a major-league franchise, worked to develop an agreement that would establish temporary seating for 13,500 fans to accommodate the fast-approaching 1953 season.25 A viable lease agreement was created and long-range plans were established to increase permanent seating accommodations for 50,000. Veeck, needing working capital, agreed to sell 20 percent of the ballclub’s stock to local businessmen.26

Believing financial plans and operational requirements had been worked out for the Browns to shift to Baltimore, Veeck sought approval of the American League. While Veeck was an outstanding entrepreneur, in many ways a visionary for the game, in the realm of intraleague politics, he was quite naїve.

His constant publicity-seeking efforts, whether by having a midget bat in a game or having fans “manage” a game, struck more staid owners as distinctly garish and therefore offensive. More seriously, his wrangling over radio and television rights and scheduling of night games created enemies. Additionally, owners were concerned that the Browns shifting to Baltimore, would hurt attendance for the Philadelphia and Washington clubs – concerns that in the end proved credible. Another argument was that if the shift were allowed, the International League’s continued viability was at risk, particularly on the eve of a new season. The proposed action was too sudden.

These and other roadblocks, including possible exposure to legal proceedings, all coalesced into the American League owners denying Veeck’s request to transfer the Browns to Baltimore by a 6-to-2 vote, with Veeck and the Chicago White Sox being the sole supporters of his request. The owners wanted Veeck out of the game.

Their feelings were soon echoed by Browns fans in St. Louis once Veeck’s plans became known. He had worked himself into a corner. The Browns were forced to stay in St. Louis for the 1953 season. Local interest in the team Veeck had built up over the previous two seasons plummeted. The Browns dropped into last place, losing 100 games. Attendance fell under 300,000. Veeck had become a pariah in the city.

By the end of 1953, several developments had taken place. Veeck sold Sportsman’s Park to Anheuser-Busch for $1.1 million. Additionally, he sold off marketable players to stave off bankruptcy. And of great collective interest to American League owners, movement of the Braves from Boston to Milwaukee proved a resounding success, with attendance soaring from less than 290,000 in Boston to over 1.8 million in Milwaukee. This was incentive to grant Veeck’s renewed interest in moving to Baltimore. Even so, his effort failed again in a 4-to-4 vote. It became clear to Veeck that the right to move to Baltimore could be approved – as long as Veeck was not part of the ownership.

Immediately after the vote denying Veeck’s efforts to move to Baltimore on September 27, 1953, Baltimore’s representatives sought to retool the proposal through several avenues. One was to hint at potential legal actions, including an assault on baseball’s sacred player reserve clause. The other was to restructure the financial package by buying out Veeck. An offer was formulated to pay Veeck’s asking price of $2.4 million. Financing was also arranged to buy the International League Orioles for $350,000 and to pay a $48,749 indemnity to the International League for its loss of Baltimore territorial rights. The American League approved the deal on October 1, enabling Bill Veeck to realize a $1 million gain on his investment and allowing the discharge of various debts as well as realize some profit for him and his fellow investors.27

With this action, the 51-year run of the St. Louis Browns ended. The team would play in Baltimore in 1954 and end up with the exact record it had in 1953: 54 wins and 100 losses. Fortunately for the Orioles, the hapless Philadelphia A’s won three games fewer, to finish in last place. Despite not improving on their 1953 performance on the field, the Orioles did something the Browns had never come close to achieving. Baltimore’s return to the majors attracted 1,060,910 fans through the turnstiles.

The shift from St. Louis to Baltimore proved to have a ripple effect on the American League. Fears that placing a team in Baltimore would oversaturate the region were proved correct: Both the Philadelphia A’s and Washington Senators saw declining attendance. After the 1954 season, the A’s moved to Kansas City. After the 1960 season the Senators franchise moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul.

GREG ERION is retired from the railroad industry and currently teaches history part-time at Skyline Community College in San Bruno, California. He has written several biographies and game articles for SABR. Greg is one of the leaders of SABR’s Baseball Games Project. He and his wife, Barbara, live in South San Francisco, California.

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck, Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker & Company, 2012), 63-69; Nick Acocella, Baseball’s Showman, espn.com/classic/veeckbill000816.html.

2 Dickson, Bill Veeck, 67-80, and 357-366. Dickson goes into depth on Veeck’s efforts as well as analyzing the validity of subsequent documentation concerning this aspect of Veeck’s career.

3 That option was obtained from Mark Steinberg, a St. Louis investment broker who had purchased the note from the DeWitts. Rumors were about that the DeWitts might sell the club to Frederick C. Miller, a Milwaukee brewer whose intentions were to shift the franchise to Milwaukee. Steinberg’s action forestalled that possibility. The note represented approximately 56 percent of the Browns stock. Bob Broeg, “Veeck’s Friend Buys Browns $700,000 Note,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1951: 4, and Frederick G. Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles: The History of a Colorful Team in Baltimore and St. Louis (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1955), 214.

4 Ray Gillespie, “Veeck Party Forms New Corporation,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1951: 2.

5 Dickson, Bill Veeck, 185-186.

6 A breakout of how shares were distributed was not publicized. “Reorganized Browns Boast Only Sixteen Shareholders,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1951: 16.

7 Ray Gillespie, “Veeck Deal Shows Rocketing Value of Major Franchises,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1953: 5, and James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1992), 400.

8 Bob Burnes, “Bill’s Magic Touch Spurs Lagging Gate,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1951: 2.

9 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck – as in Wreck: The Chaotic Career of Baseball’s Incorrigible Maverick” (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 213.

10 Bob Burnes, “Sports Shirt Veeck Collars Browns Fans,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1951: 4.

11 Veeck and Linn, Veeck, 215.

12 Gaedel pinch-hit for the aforementioned Saucier, who would have only 14 at-bats in his abbreviated career.

13 The fans who “managed” were winners of an essay contest. The Browns won, 5-3. Dickson, Bill Veeck, 191-196.

14 Gerald Eskenazi, Bill Veeck: A Baseball Legend (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1988), 105.

15 Ray Gillespie, “Owner Given 15 Months, $15,000 Fine,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1953: 11.

16 Dan Daniels, “3 Trustees to Be Named to Run Club,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1953: 4.

17 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000), 56, 397.

18 Ray Gillespie, “Head of Beer Firm Is New Prexy of Club,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1953: 3.

19 Dickson, Bill Veeck, 208.

20 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 283.

21 Veeck and Linn, Veeck, 281-282.

22 Originally built as a football stadium, it was eventually reconfigured in 1950 to host the minor-league Orioles. Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 18.

23 James Edward Miller, The Baseball Business: Pursuing Pennants and Profits in Baltimore (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 29.

24 Jack Dunn III, with whom Veeck was dealing, is not to be confused with his grandfather, who owned the International League Baltimore Orioles in the 1920s. baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jack_Dunn_III.

25 D’Alesandro’s daughter, Nancy Pelosi, became speaker of the US House of Representatives in 2007.

26 Veeck’s attempt to transfer and then sell the Browns is detailed in Miller, The Baseball Business, 29-35.

27 Miller, The Baseball Business, 35.