Brooklyn, The Dodgers … and The Movies

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

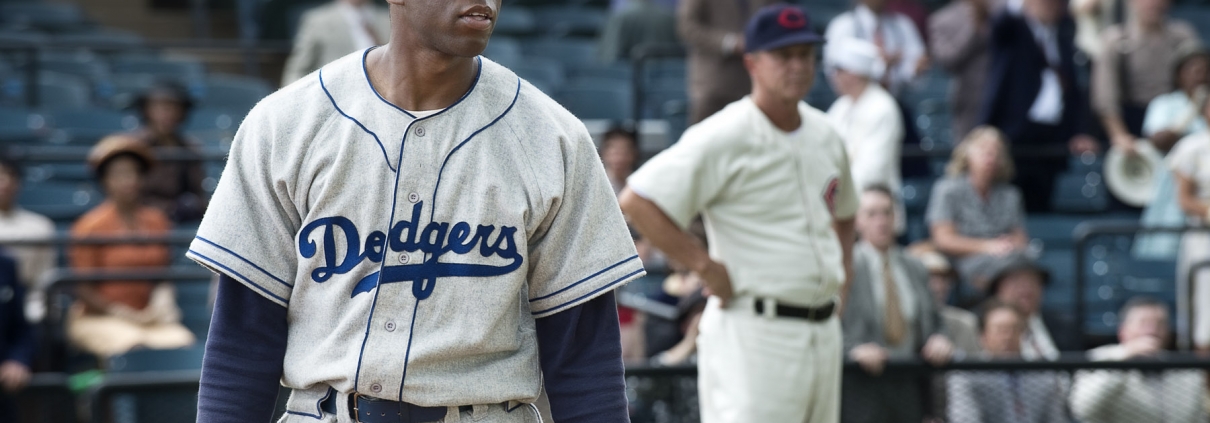

As major league ballyards across America were celebrating the 2013 baseball season’s Opening Day, a high-profile new film about a deceased player from a bygone team came to movie theaters. That film was 42 — a biopic charting the life and legend of Jackie Robinson of the beloved Brooklyn Dodgers.

While addressing the crowd at Cooperstown’s Doubleday Field during Hall of Fame weekend later that summer, Thomas Tull, the film’s producer — whose credits range from The Dark Knight to The Hangover to Ninja Assassin — observed that 42 is “the most important film I’ll ever do.” And he added: “After making Batman, Superman, and other superhero movies, the greatest ‘superhero’ movie that could be made is about Jackie Robinson.”1

While addressing the crowd at Cooperstown’s Doubleday Field during Hall of Fame weekend later that summer, Thomas Tull, the film’s producer — whose credits range from The Dark Knight to The Hangover to Ninja Assassin — observed that 42 is “the most important film I’ll ever do.” And he added: “After making Batman, Superman, and other superhero movies, the greatest ‘superhero’ movie that could be made is about Jackie Robinson.”1

Yet this recent Jackie film is not the first.2 Way back in 1950 — 63 years earlier — the ballplayer’s struggles were depicted in The Jackie Robinson Story. That film may cover essentially the same territory as 42, but the earlier version is a mirror of its era and a valuable social history. Beyond the rare pleasure of seeing the real number 42 playing himself and reciting his lines, the scenario deals with issues that transcend singles, doubles, and dingers. The Jackie Robinson Story dates from the dawn of the civil rights movement; when it was released, 21-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. had recently received his B.A. from Morehouse College and was a second-year student at Crozer Theological Seminary. Brown v. Board of Education was four years in the future and the signing into law of the Voting Rights Act would be 15. No one could foretell the scope of the demand by black Americans to embrace equal rights with white Americans, but Hollywood, after years of marginalizing black characters, was belatedly acknowledging its biased depiction of African-Americans; previously, the industry consistently had trivialized them as stereotypical mammies and janitors, train porters and shoeshine boys whose eyes popped out of their heads while they fractured the English language.

The Jackie Robinson Story put forth the idea that for every exclusionary bigot in America, there is a man who is fair and humane, a man who would judge Jackie solely on his performance between the foul lines. In other words, for every racist, there is a Branch Rickey. The Jackie Robinson Story heralded a new, refreshing — and, by 1950s standards, radical — celluloid depiction of black Americans and racism American-style. Plus, its star was not the lone future Hall of Famer appearing onscreen. Dick Williams, then a 20-year-old Brooklyn minor leaguer, is in two sequences, playing two different roles. “First, I was a second baseman,” he recalled. “They shot that in one day. The next day, they needed a pitcher. So I did that, too.”3 In the film, there is extensive footage of Williams as the Jersey City hurler who pitches to Jackie in his first minor league game.

Of course, not all Brooklyn-centric baseball films highlight Jackie Robinson, or even the Dodgers. Rhubarb (1951) is a slapstick about a tough, spirited alley cat who is taken in by the eccentric millionaire owner of the big-league Brooklyn Loons. Upon his master’s demise, Rhubarb becomes the principal heir, inheriting $30-million — not to mention those lovable Loons. Baseball also plays a small but significant role in The Chosen (1982), an adaptation of the Chaim Potok novel. The setting is World War II and the story opens with boys playing ball in a Brooklyn schoolyard. One team is consists of Americanized Jews while the other is made up of Hasidic Jews; their competition illustrates their collective assimilation into the American mainstream at a time when those left behind in Europe were being slaughtered by Adolf Hitler.

But films like Rhubarb and The Chosen are the exceptions. Prior to the Dodgers abandoning Brooklyn for the California orange groves, the borough and its big league nine were inexorably linked by Hollywood. On occasion, they were united in entire films, while other storylines only featured Dodgers references or sequences. As a whole, however, these films capture the flavor of baseball Ebbets Field-style, with the wear-your-emotions-on-your-sleeve enthusiasm of the Dodgers diehards.

Perhaps the quintessential Brooklyn baseball film is one that is little-seen and barely remembered. Though the names of Hall of Famers Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Dazzy Vance, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Tony Lazzeri are casually dropped into the script, neither the Dodgers nor Ebbets Field are cited by name. Still, It Happened in Flatbush (1942) embodies the essence of the borough during a long-ago era. Though the on-screen image is that of the Brooklyn Bridge, the opening credits feature a soundtrack of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

The scenario charts what happens when Frank Maguire (Lloyd Nolan), a washed-up ex-ballplayer who “used to be shortstop for Brooklyn,” is resurrected as the team’s skipper. Upon his hiring, the team’s owner tells Maguire: “See you in New York” — and he is quick to respond: “Not New York. Brooklyn.” The woman who eventually inherits the club is no baseball fan. We know this because she resides in Manhattan, whose residents are referred to as “foreigners.” And Brooklyn is labeled “the best baseball town in America,” with its residents loudly, endlessly arguing — and not just about sports. But bats and balls are at the core of the story. One fan even rushes onto the field to belt an umpire, while another proudly declares: “Baseball belongs to the people, and the Brooklyn team belongs to us.”

The Dodgers are cited by name in other period titles. Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942) stars Ginger Rogers as a Brooklynite who came of age near Ebbets Field and who quips: “Foul balls used to light in my backyard” before sighing “Dem lovely Bums.” The opening sequence in Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) features loudmouthed Dodgers fanatics and brawling players at Ebbets Field. The It Happened in Brooklyn (1947) scenario stresses that every genuine Brooklynite knows that the Ebbets address is “Bedford and Sullivan”; upon arriving home after four years in the military, Brooklynite Frank Sinatra immediately spots a poster advertising a ballgame (“Game Today Ebbets Field Dodgers vs. Cubs”). The musical The West Point Story (1950) includes a “Brooklyn” production number, one of whose lines is: “They know my shield from Ebbets Field to Cheyenne…” The Dodgers first — and lone — World Series title is acknowledged in The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956), the tale of a stressed-out suburbanite (Gregory Peck) who travels into Manhattan by train every workday. On one occasion, the man sitting beside him dourly declares: “There’s no use trying. I just can’t get used to it.” “Used to what?” he asks. His fellow commuter responds: “The idea of the Brooklyn Dodgers as world champions.”

Big Leaguer (1953) was made two years after Bobby Thomson’s shot-heard-round-the-world resulted in the Dodgers’ embracing defeat yet again. Though the film is New York Giants-centric — with Edward G. Robinson playing “Hans” Lobert, an ex-big leaguer who runs a Giants’ Melbourne, Florida tryout camp — the finale features a game between the Giants prospects and Dodgers rookies. The Brooklynites are leading, 7–4, in the ninth inning when Carl Hubbell, on hand to evaluate Lobert’s players, offers insight into the heart of baseball by observing: “The game’s now getting interesting.”

Among all the actors who’ve played fans of all stripes, the one who embodies the essence of the baseball zealot is William Bendix. Certainly, Bendix’s role in baseball movies extends way beyond his characterization of The Bambino in The Babe Ruth Story (1948) — arguably one of the worst-ever baseball biopics. For indeed, during World War II, one of the character types found in a typical military unit in a typical Hollywood war movie is played most memorably by Bendix: the energetic Brooklynite, a lovable “woiking class” Joe who endlessly blabs on about Dem Bums while bullets from the guns of the heinous “Japs” and “Krauts” zip by overhead. For after all, weren’t our boys in uniform battling Hitler, Tojo, and Mussolini to preserve baseball as much as mom’s apple pie and the red, white, and blue?

In Guadalcanal Diary (1943), Bendix plays Taxi Potts, an affable jokester and Brooklyn cabbie-turned-US Marine. The film opens with Potts and his fellow GIs on board a transport somewhere in the South Pacific, heading for a Japanese beachhead. “If I was back home, I wouldn’t be on no boat…,” he quips. “Ebbets Field. That’s for me. Watchin’ them beautiful Bums… Just leadin’ the league… That’s all, just leadin’ the league… You got any dough which says the Yanks’ll take the Bums in the Series?” (The year is 1942 and, later on, the Marines listen to a World Series radio report in which the Bronx nine faces off against… the St. Louis Cardinals!) But Potts’s Dodgers devotion is endless. Just before landing at Guadalcanal, he admits: “…times like these kinda make me wish I was back in Brooklyn, drivin’ my cab with the fast meter and keepin’ an eye on them Bums.” While digging a foxhole, he notes: “Maybe if we dig deep enough, we’ll come up somewhere around Ebbets Field.”

Not all of Bendix’s Borough of Churches characters are in the military. In Lifeboat (1944), he plays Gus Smith, a stoker on a freighter destroyed by a German U-boat. “What a day for a ballgame,” he feverishly declares while struggling to maintain his sanity on the lifeboat. The Cardinals may be “the team to watch this year” because they “got hitters… Stan Musial’s been clubbin’ ’em,” but he adds: “If the Dodgers only had a guy like Ernie Bonham, or even Johnny Humphries.” He then conjures up a fictional game between Brooklyn and Pittsburgh. The pitching matchup will “probably be [Whitlow] Wyatt for the Dodgers, [Rip] Sewell for the Pirates. I think I’ll take Rosie (to) Ebbets Field. It’s gonna be a good game this afternoon.”

The actor also portrays a baseball-loving Brooklynite in a trio of Hal Roach “streamliners”: films with lengths between that of a short subject and feature. Their titles are Brooklyn Orchid (1942); The McGuerins from Brooklyn, also known as Two Mugs from Brooklyn (1943); and Taxi, Mister (1943), all of which chart the misadventures of Tim McGuerin (Bendix) and Eddie Corbett (Joe Sawyer), the rough-hewn but affable co-owners of a Brooklyn taxi company.

The McGuerins from Brooklyn may have been advertised as a comedy in which Bendix and Sawyer “…Bat Out Laughs Like the Dodgers Bat Out Runs,” but baseball is most prevalent in Taxi, Mister. The scenario has McGuerin pitching on a sandlot ball team; Corbett is the catcher; their nine is named for one of the most celebrated Brooklyn neighborhoods: Flatbush. A mobster plots to do in McGuerin during a game but, in a sequence which ends in a free-for-all, the pitcher’s ability to throw a wicked curveball allows him to knock out the bad guy.

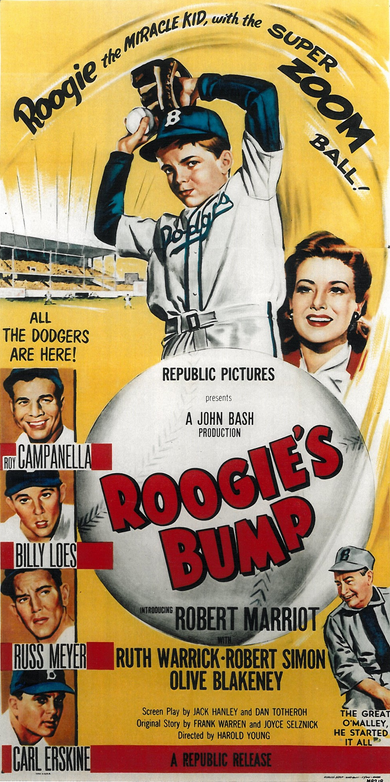

On other occasions, real-life Dodgers show up onscreen. Whistling in Brooklyn (1943) stars Red Skelton as a popular radio sleuth who is involved in off-the-air murder and mayhem; he comes to Ebbets Field and mixes with Leo Durocher, Arky Vaughan, Ducky Medwick, and Billy Herman, among others. Plus, as Herman comes to bat, who should appear on-camera but the inimitable Hilda Chester, Dodgers fan extraordinaire. (Hilda, Leo, Pee Wee Reese, Pete Reiser, Eddie Stanky, and Red Barber appear in Brooklyn, I Love You, a Paramount short subject spotlighting the Dodgers’ 1946 campaign.) Billy Loes, Carl Erskine, Russ Meyer, and Roy Campanella play themselves in Roogie’s Bump (1954), a Rookie of the Year precursor involving a little boy who, via the maneuvering of Red O’Malley, a deceased Dodgers pitching star, becomes the “miracle kid with the super zoom ball” who fires horsehides with the “speed of light.” Walter O’Malley is not to be seen but his influence is obvious, as hurler O’Malley is nothing less than saintly, and even is patronizingly referred to as the “Great O’Malley.”

On other occasions, real-life Dodgers show up onscreen. Whistling in Brooklyn (1943) stars Red Skelton as a popular radio sleuth who is involved in off-the-air murder and mayhem; he comes to Ebbets Field and mixes with Leo Durocher, Arky Vaughan, Ducky Medwick, and Billy Herman, among others. Plus, as Herman comes to bat, who should appear on-camera but the inimitable Hilda Chester, Dodgers fan extraordinaire. (Hilda, Leo, Pee Wee Reese, Pete Reiser, Eddie Stanky, and Red Barber appear in Brooklyn, I Love You, a Paramount short subject spotlighting the Dodgers’ 1946 campaign.) Billy Loes, Carl Erskine, Russ Meyer, and Roy Campanella play themselves in Roogie’s Bump (1954), a Rookie of the Year precursor involving a little boy who, via the maneuvering of Red O’Malley, a deceased Dodgers pitching star, becomes the “miracle kid with the super zoom ball” who fires horsehides with the “speed of light.” Walter O’Malley is not to be seen but his influence is obvious, as hurler O’Malley is nothing less than saintly, and even is patronizingly referred to as the “Great O’Malley.”

Three years later, the Dodgers abandoned Brooklyn and O’Malley no longer was “great” — at least in the souls of Brooklynites. Sweet Smell of Success came to theaters in June 1957, scant months before the team’s Brooklyn swan song. In the film, slimy press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) tells the secretary of ruthless newspaper columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster): “Don’t try to sell me the Brooklyn Bridge. I happen to know it belongs to the Dodgers.” But Falco was of course dead-wrong. This repartee is contrasted to another Tony Curtis film: Some Like It Hot (1959), which is set in Chicago in 1929. The following dialogue may be lost on twenty-first-century viewers who are neither baseball, movie, nor American history savvy, but it resonated with then-contemporary moviegoers. At one point, saxophonist Joe (Curtis) queries his pal Jerry (Jack Lemmon), a double-bass player: “Jerry boy, why do you have to paint everything so black?… Suppose the stock market crashes. Suppose Mary Pickford divorces Douglas Fairbanks. Suppose the Dodgers leave Brooklyn…”4

For decades after their departure, Brooklyn Dodgers nostalgia permeated American movies. In Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), a father (Dustin Hoffman) who hails from the borough tells his son (Justin Henry) about his childhood: “We listened to the radio… We didn’t have diet soda. We had egg creams… We didn’t have the Mets, but we had the Brooklyn Dodgers. And we had the Polo Grounds. And we had Ebbets Field. Oh boy, those were the days.” Fact and fiction merge in Simple Men (1992), featuring a central character who was the Dodgers’ all-star shortstop during the 1950s — and who is decidedly not Pee Wee Reese. After his playing career ended, the ballplayer (known as “Dad,” played by John MacKay) became an anarchist who allegedly tossed a bomb at the Pentagon during the late 1960s, killing seven people. But in no way is his baseball career marginalized. “I saw your father play with the Dodgers back in ’56,” a cop tells one of his sons. “He was the greatest shortstop who ever lived, no matter what anyone says about him.”

Brooklyn (2015), based on Colm Tóibín’s novel and set in the early 1950s, is the story of Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan), a shy Irish lass who leaves her smalltown home, sets off for America, and settles in the title borough. Once there, Eilis is pursued romantically by Tony (Emory Cohen), a blue-collar Brooklynite of Italian extraction who lives and breathes Dodger-blue. At one point, Eilis is told that she will “have to go to Ebbets Field if you want to see (Tony) in the summer.” She then asks Tony: “They’re that important to you?” And he responds: “Put it this way, if our kids end up supporting the Yankees or the Giants, it would break my heart.”

A far less misty-eyed take is found in Smoke and Blue in the Face (both 1995), based on works by Newark, New Jersey native and longtime Brooklyn resident Paul Auster, which offer portraits of the borough pre-gentrification. At one point, one of its characters, who is old enough to recall the Dodgers in Brooklyn, tellingly explains: “If there was probably a childhood trauma that I had, other than the Dodgers leaving Brooklyn which, if you think about it, is a reason why some of us are imbued with a cynicism that we never recovered from. Obviously, you’re not a Mets fan and you can’t possibly be a Yankee fan. So baseball is eliminated from your life, because of being born in Brooklyn.” And he concludes: “Maybe I don’t like baseball because the Dodgers aren’t here anymore…”

The title character in The Angriest Man in Brooklyn (2014) is no grouchy golden ager who also misses Dem Bums. He is Henry Altmann (Robin Williams), a perpetually enraged (not to mention terminally-ill) individual. Altmann is surrounded by hostile, endlessly kvetching Brooklynites; however, a once-upon-a-happier-time is represented in a black-and-white photo of two Dodgers jacket-clad boys posing with their father in Ebbets Field.5

Finally, during the 2016 presidential race, My X-Girlfriend’s Wedding Reception (1999), an otherwise obscure low-budget throwaway, became a hot online ticket. The reason: Playing a rabbi named Manny Shevitz — remember, this is a comedy — is none other than Bernie Sanders. He is billed as “Congressman Bernie Sanders” and his yarmulke-clad character addresses the wedding guests by observing: “Today we celebrate life: a very sacred part of life.” That’s fair enough, coming from a rabbi. But then Rabbi Manny, after declaring that he, like the man who plays him, was born and bred in Brooklyn, goes on a riff about the tragedy of the Dodgers leaving the Borough of Churches. Then, as if addressing a convention of sports fans rather than a wedding party, he segues into a criticism of baseball free agency.

ROB EDELMAN teaches film history at the University at Albany. He authored “Great Baseball Films” and “Baseball on the Web,” and, with his wife Audrey Kupferberg, “Meet the Mertzes,” a double biography of “I Love Lucy’s” Vivian Vance and famed baseball fan William Frawley. A frequent contributor to SABR journals and to “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game,” he has written articles on baseball and pop culture for many publications.

Notes

1. http://wamc.org/post/rob-edelman-now.

2. Robinson also is the central character in two made-for-TV movies. Andre Braugher plays him in The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson (1990), involving his plight upon refusing to move to the back of a bus while in the US Army during World War II. Blair Underwood plays him in Soul of the Game (1996), centering on his interaction with Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson at the time of his signing by Branch Rickey. In Blue in the Face (1995), Keith David appears as the ghost of Jackie Robinson. And in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), Mookie the pizza delivery guy (played by Lee) comes to work garbed in a number 42 jersey. But Jackie is missing from another TV movie: It’s Good to Be Alive (1974), a Roy Campanella biopic.

3. Rob Edelman. “The Jackie Robinson Story: A Reflection of Its Era,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture, Fall 2011, 40–55.

4. A link between Brooklyn past and present is found in Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), which is written up in detail in “More Baseball in Non-Baseball Films,” published in the Spring 2015 issue of the Baseball Research Journal (76–82). To summarize: The time is World War II and Brooklyn-born 90-pound weakling Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) has been transformed into the muscular title character. At one point, he hears a Dodgers-Phillies game broadcast on the radio from Ebbets Field. Only there’s a problem. The scenario may be set during the war, but this particular contest was played pre-Pearl Harbor: in May 1941. He knows this because he was in the stands; the fictional Steve Rogers was one of the 12,941 fans on hand that day. Something is amiss … and this knowledge on Rogers’s part further propels the plot.

5. Pictured in the 1955 photo is five-year-old Phil Alden Robinson (the director of The Angriest Man in Brooklyn as well as Field of Dreams), his older brother, and their father.