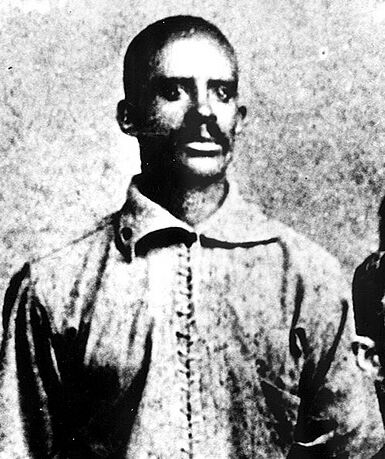

Bud Fowler, Black Baseball Star

This article was written by L. Robert Davids

This article was published in Road Trips: SABR Convention Journal Articles

This article was originally published in the 1991 SABR convention journal (New York City). In 2020, Bud Fowler was selected as SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legend.

New York state made a significant contribution to black baseball in the 19th century. Not only did such great independent clubs as the Cuban Giants and the New York Gothams originate here, but several of the top Negro players performed on state teams in organized baseball. Frank Grant spent three seasons with Buffalo in the International League, 1886-1888; Moses Walker caught for Syracuse in 1888-1889; George Stovey pitched briefly for Troy in 1890; and Bud Fowler starred for Binghamton in 1887. Fowler, however, was the only one to have roots in the Empire State.

New York state made a significant contribution to black baseball in the 19th century. Not only did such great independent clubs as the Cuban Giants and the New York Gothams originate here, but several of the top Negro players performed on state teams in organized baseball. Frank Grant spent three seasons with Buffalo in the International League, 1886-1888; Moses Walker caught for Syracuse in 1888-1889; George Stovey pitched briefly for Troy in 1890; and Bud Fowler starred for Binghamton in 1887. Fowler, however, was the only one to have roots in the Empire State.

Census and family information indicate that he was born John J. Jackson in Fort Plain, N.Y., on March 16, 1858, the son of John and Mary Lansing Jackson. The New York census of 1860 placed the family in Cooperstown, where the father was a barber. The same applies to 1870, at which time son John was listed as 13 and “attended school within the year.” It is good to know that a century before Satchel Paige was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, an adolescent black boy was already familiar with that upstate village and developing his ballplaying talents.

No firm information is available on when Fowler began his baseball career—the New York Age of Feb. 25, 1909, said it was 1873 in Binghamton — or when and where he took the name of Fowler. It is known that the nickname “Bud” resulted from his inclination to call most others by that name.

FOWLER’S DEBUT

The first documented mention of Fowler as a player was in April 1878, when he pitched for the Chelsea team in Massachusetts. On April 24, he hurled an exhibition game victory over the Boston Nationals of George Wright, Jim O’Rourke and company, besting Tommy Bond 2-1. When the Lynn Live Oaks of the International Association (the first minor league) lost their lead pitcher to illness, they acquired Fowler from Chelsea. The Boston Globe reported on May 18 that “Fowler, the young colored pitcher of the Chelseas,” held the Tecumsehs of London, Ont., to two hits and was leading 3-0 in the eighth inning when the Canadians became irked over an umpire’s decision and left the field. Lynn won by forfeit. Fowler pitched two more league games, losing to Syracuse and Utica. However, he did break the color line in organized baseball.

Fowler pitched in the Boston area in 1879 and next surfaced in Guelph, Ont., in 1881 when the local Maple Leafs signed him to pitch for them. However, his presence on the otherwise all-white club was vigorously opposed by one vocal member who led a revolt among his teammates. Fowler was dropped from the squad and wound up playing with the Petrolia Imperials. The Guelph Herald had this to say: “We regret that some members of the Maple Leafs are ill-natured enough to object to the colored pitcher Fowler. He is one of the best pitchers on the continent of America and it would be greatly to the interest of the Maple Leaf team if he was re-instated He has forgotten more about baseball than the present team ever knew and he could teach them many points in the game.”

Fowler was still primarily a pitcher when he was signed by Stillwater, Minn., in 1884 to play in the strong Northwestern League. Stillwater had one of the weaker franchises compared to Fort Wayne, Grand Rapids, Milwaukee, Minneapolis and St. Paul. In fact, the club lost its first 16 games before Fowler broke the spell with complete-game victories on May 26, 28,29 and 31. He had several losses after that and started to play at other positions. On June 15 the St. Paul Dispatch noted that Fowler was presented with a $10 bill and a suit of clothes for his strong contribution to the win over Fort Wayne.

On June 23, however, he was “fined $10 for the wild throw he made in Saturday’s game.” He apparently was not asked to return the clothes. Stillwater dropped out of the league in August, one of several clubs that disintegrated for one reason or another while Fowler was a team member.

In 1885 he was with Keokuk, Iowa, for only eight games before that team collapsed. His next stop was Pueblo in the Colorado League, where he played five different positions in five games. Two interesting newspaper quotes resulted. The Denver Rocky Mountain News reported that “Fowler has two strong points: He is an excellent runner and proof against sunburn. He don’t tan worth a cent.” The Pueblo Chieftain of Aug. 18, 1885, stated: “Fowler bats right- or left-handed. It all depends on whether there is a man on first or third.”

That last quote is the only recorded mention that Fowler might have been a switch hitter on occasion. Similarly, it should be noted that Carl Sandburg, the author and historian, mentioned in his 1954 autobiography Always the Young Strangers that he remembered as a youth in Galesburg, Ill., watching “its second baseman, professional named Bud Fowler, a left-handed Negro, fast and pretty in his work.” That is the only recorded mention that Fowler ever threw left-handed. However, it is known that he played to the crowd, that he was innovative, unpredictable and superstitious. It is entirely possible that playing second without a glove he could throw left-handed. Surely, if he had been a natural southpaw, it would have been mentioned during his pitching career, for left-handed hurlers were rare in those days.

In 1886, Fowler led the Western League in triples and helped lead Topeka to the pennant. Returning to New York state the next year, he probably achieved his highest level of play with Binghamton. While he had been the only black in the Western League, there were seven in the International League in 1887. The list included pitcher George Stovey, who won 34 games for Newark; Moses Walker, his catcher; and Frank Grant of Buffalo, who led the league with 11 home runs. In a game report on May 8, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle said: “The main interest was centered on two colored second basemen, Grant of the Buffaloes and Fowler of the Binghamtons” The paper concluded that Fowler “played the best game and won much applause” as the Bingos triumphed 8-7.

The league acquired another black player on May 31 when Oswego signed a Negro second baseman by the name of Randolph Jackson. He was from Ilion, N.Y., and had been “recommended by Fowler of the Binghamtons.” There is speculation that Jackson might have been a cousin of Fowler, aka John Jackson.

MOUNTING RACIAL PROBLEMS

In the meantime, racial problems were building on the Binghamton club. Their fielders played poorly behind pitcher William Renfroe, a black teammate of Fowler who had the same experience when he pitched for Stillwater in 1884. The Chronicle reported on July 5 that Fowler had been released “upon condition that he will not sign with any other International club.” He had batted .350 in 34 games. The Bingos folded later in August, at which time Fowler was playing with Montpelier, where he “seemed to be the favorite with the spectators and was greeted with applause every time he stepped to the plate.”

Fowler continued to play with white league teams whenever he could; however, his tenure was typically brief. He did play the full schedule with Greenville in the Michigan State League in 1889, and led the Nebraska State League in stolen bases in an aborted season in 1892. But in four seasons he played with 10 different teams. In 1893 to 1894 he played with an independent team in Findlay, Ohio, and served as a barber (his father’s occupation) there in the off-season.

With the prospect of playing in white leagues virtually eliminated. Fowler, with Findlay teammate Grant (Home Run) Johnson, organized the Page Fence Giants and toured through the Middle West in 1895. Ironically, Fowler left the team on July 15 to play in the Michigan State League. He may have enjoyed more the individual attention he received playing on mostly white teams and this turned out to be his last opportunity to play in the minors. It was his 10th year as an official minor leaguer, four more than achieved by any other black player.

Fowler then returned to Findlay, where he continued to play until July 1899 when the white members drew the color line and said they would quit if Fowler was not ousted from the team. He then turned to organizing black clubs to play against college, independent and minor league teams. He also tried to organize a black league, but the financial resources were not forthcoming. A new generation of baseball fans was reminded of Fowler’s contributions as player and manger when Sol White’s History of Colored Baseball was published in 1907. White, who played on Fowler’s Page Fence Giants in 1895, called him “the celebrated promoter of colored ball clubs and the sage of baseball.”

On Feb. 25, 1909, the New York Age ran an article on Fowler saying he was ill at the home of his sister in Frankfort, N.Y., and plans were being made to hold a benefit game for him in Ridgewood, N.J., near where he had been living. The game was postponed because of difficulty in getting the players together and apparently never was played.

The next mention of Fowler was his obituary in the Herkimer Evening Telegram of March 1, 1913. He had been taken ill at his home in New York City and returned to his sister’s home in Frankfort, where he died on Feb. 26, just short of his 58th birthday. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Frankfort Cemetery.

On July 25, 1987, in a memorial program at the cemetery, the Society for American Baseball Research unveiled an appropriately engraved stone marker in the presence of the mayor, city and state officials, in addition to Monte Irvin and other former Negro League players, Little League team members and SABR members among a total audience of about 200. The black baseball pioneer who made a historically important impact on 19th-century baseball finally received the recognition he deserved.