Claimed Off the Waiver List: Hall of Fame Castoffs

This article was written by David Surdam

This article was published in 2000 Baseball Research Journal

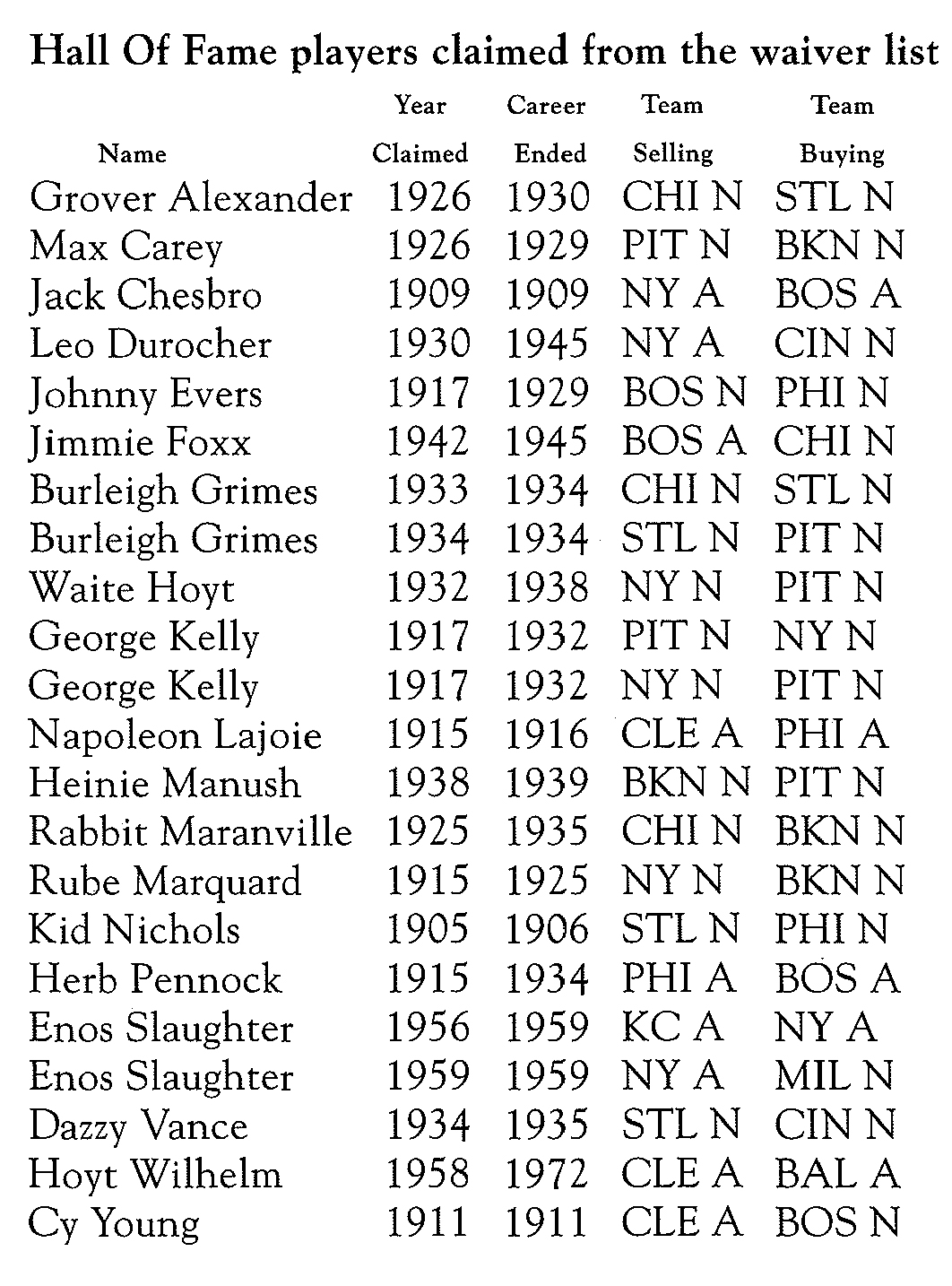

Most baseball fans pay scant attention to the waiver list, and, given the lackluster talent appearing on the list, perhaps this is an astute use of their time. However, nineteen future Hall of Fame players have been claimed from the waiver list. Of course, at the time, no one knew that most of these players were future Hall of Famers (many were claimed before the Hall of Fame was even a promoter’s dream). One of them, Leo Durocher, reached the Hall of Fame primarily on his managerial accomplishments. Three of them — Burleigh Grimes, George Kelly, and Enos Slaughter — were claimed on waivers twice during their careers, with Kelly being shuttled between the Giants and Pirates twice during ‘1917.

As the accompanying list demonstrates, most of these players were near the end of their careers. Jack Chesbro, Johnny Evers, Jimmie Foxx, Burleigh Grimes, Heinie Manush, Kid Nichols, Dazzy Vance, and Cy Young provided few benefits to the teams paying the waiver price for them. Although Evers’ career technically ended in 1929, this is misleading. He played two games after his 1917 waiver year: one in 1922 and one in 1929. Jimmie Foxx hit only seven home runs after the 1942 season. Only the exigencies of World War II kept him in the major leagues.

While several other players were clearly on the decline, they had a couple of productive seasons left. The St. Louis Cardinals claimed Grover Alexander on waivers midway through the 1926 season. He won nine games for the Cardinals, as the team won the National League pennant. During the 1926 World Series, he provided a moment of drama by striking out Tony Lazzeri. He won twenty-one games in 1927 and won fifty-five games for the Cardinals before ending his career in 1930.

Enos Slaughter became a useful backup outfielder for the New York Yankees during the late 1950s, even hitting over .300 one season. Waite Hoyt won fifteen games with Pittsburgh in 1934, after being claimed on waivers in 1932. In all, he won thirty-five games for the Pirates.

Max Carey played regularly for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1927, batting a mediocre .266.

Napoleon Lajoie started at second base for two seasons on his second tour with the Philadelphia Athletics, but he averaged just .264 during those two seasons (about .150 below his average with the Athletics during his first stint with the team). He was a regular primarily because Connie Mack had depleted the team after the 1914 World Series fiasco. Mack needed money during the war with the Federal League and had sold Eddie Collins, among others.

Rube Marquard had compiled three brilliant seasons (a combined 73-28 win-loss record) with John McGraw’s Giants, 1911-1913, but floundered thereafter. The Dodgers claimed him off the waiver list during the 1915 season. He went 13-6 for the pennant-winning Dodgers in 1916 and 19-12 in 1917. While he started a game in the 1920 World Series, he lost more games than he won during the next three seasons-at least partly because of poor support. Marquard later pitched for Cincinnati and the Boston Braves. He won ninety-eight games after being claimed on waivers.

Rabbit Maranville was claimed on waivers by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1925, just past the midpoint of his career. He didn’t do well with the Dodgers, hitting just .235, but later returned to the Boston Braves and played regularly for several seasons. While he is in the Hall of Fame, it certainly wasn’t for any hitting prowess. Even during the hit-happy 1920s, Maranville had trouble hitting over .280, and his election to the Hall of Fame remains a mystery to many.

The three remaining players are baseball’s equivalent to finding wheat among the chaff. George Kelly had performed poorly for John McGraw’s Giants between 1915 and 1917, so McGraw placed him on the waiver list. Pittsburgh claimed him, but he hit for less than half his weight for the Pirates. Pittsburgh placed him back on the waiver list, and McGraw re-acquired him. After missing the 1918 season due to military service, he returned to New York and blossomed into a productive power hitter. He hit over .300 for six consecutive seasons, while driving in over 100 runs in each season from 1921 through 1924.

Herb Pennock had shown occasional glimpses of talent with Connie Mack’s Athletics. With Hall of Fame teammates Eddie Plank and Chief Bender, as well as talented youngsters Bob Shawkey and Joe Bush, Pennock was a second-line starter in 1914. He went 11-4 that season, but struggled to a 3-6 mark in 1915 prior to being placed on the waiver list. Mack’s impatience with the young pitcher proved disastrous, as Pennock would win another 223 games with the Yankees and Boston Red Sox. He won 70 percent or more of his decisions in four seasons.

One of the last Hall of Fame players ever placed on the waiver list, Hoyt Wilhelm, was problematic. Catchers found his knuckleball difficult to handle, and despite some fine seasons as a relief pitcher for the New York Giants early in the 1950s, Wilhelm became a well-traveled pitcher. In 1958 Cleveland placed him on the waiver list. In fairness to Cleveland, Wilhelm’s efforts in 1957 led to his worst earned run average (4.14) until the very end of his career. The Baltimore Orioles picked him up, and, unlike every other team he ever toiled for, attempted to use him consistently as a starting pitcher. He started over forty games with the Orioles, including a reasonably successful 1959 season in which he won fifteen games and led the league in earned run average. Despite a 1.94 earned run average in 1962, Baltimore included him in the Luis Aparicio trade. Eventually, Wilhelm appeared in 1,070 major league games, a record surpassed only by Dennis Eckersley and Jesse Orosco. Wilhelm achieved his exemplary 2.52 lifetime earned run average by being stingy with base hits, allowing just over seven per nine innings. For a knuckleball hurler, his 3.1 walks per nine innings was quite respectable. Surprisingly, he never led the league in games saved.

In the forty seasons since Enos Slaughter was claimed on waivers, no other Hall of Fame players have appeared on the list. This absence is due, in part perhaps, to the unknown Hall of Fame status of current players and players from the 1970s and 1980s. Still, the next time you peruse the “Player Transactions” list in the local paper, you might dream of your team unearthing a real diamond.

DAVID G. SURDAM is a visiting assistant professor of economics at the Graduate School of Business of the University of Chicago.

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, Ninth Edition, 1993.

The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball 1999. Edited by David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999.